The most striking thing about "Babies" isn't any one image or moment, although a fair number are arresting. It's how moviegoers react to the film as a whole.

I saw Thomas Balmes' documentary chronicling a year in the lives of four infants from four countries in regular release this past Saturday night in a packed lower Manhattan theater. I was apprehensive going in, not just because I'd read reviews that described it as either irresistible or tiresome -- and either way, as conceptually daring as a sippy cup -- but because it has become almost impossible to attend any theatrical film anywhere without enduring cross-talk, cellphoning, texting, seat-kicking, and other forms of loutish behavior.

Amazingly, for 79 minutes and change, a couple of hundred paying customers in one of the world's least patient cities gave "Babies" their undivided attention.

A quick survey of friends in other states who also saw "Babies" over the weekend -- to the tune of a respectable $1.5 million the same weekend as the blitzkrieg of "Iron Man 2" -- confirmed this was not an isolated response. People are riveted by this movie in a way that they most assuredly would not be riveted by real-life babies, unless said babies were 1) related to them, 2) professionally entrusted to their care, or 3) keeping the entire friggin' block awake with their colicky bleating.

Even if the subject matter were guaranteed box-office insurance (and I don't think it is -- prior documentaries about babies and parenting failed to escape the art-house ghetto), Balmes' primitivist film storytelling would likely neutralize it.

There's little music in "Babies," no narration and few title cards. Most of its running time consists of long, uncut, static wide shots of babies being babies: playing, gurgling, babbling. By all rights, such a no-frills approach should grind down even the most sentimental viewer's patience like a teething biscuit. (Village Voice contributor Dan Kois' abstract, Gertrude Stein-ish review is as rude as it is accurate.) Yet the pin-drop silence continues throughout the movie's running time, punctuated only by expected, appropriate reactions: laughter, awwwws, and sotto-voiced conversations between parents and formula-fed tots about what, exactly, that infant is doing with mommy's booby.

I don't think the movie's communion with audiences can be explained by its subject matter, its nurturing by deep-pocketed distributor Focus Features, or even its appealing trailer, which doubled as a viral video. (Though promoters of all kinds should note how that trailer spread. As experts told an audience at a South by Southwest panel on how to make a successful viral video, "Most videos that go viral spread happiness.") Yes, marketing and promotion drive people to the box office. But once viewers take their seats, they either like the movie or they don't. Period.

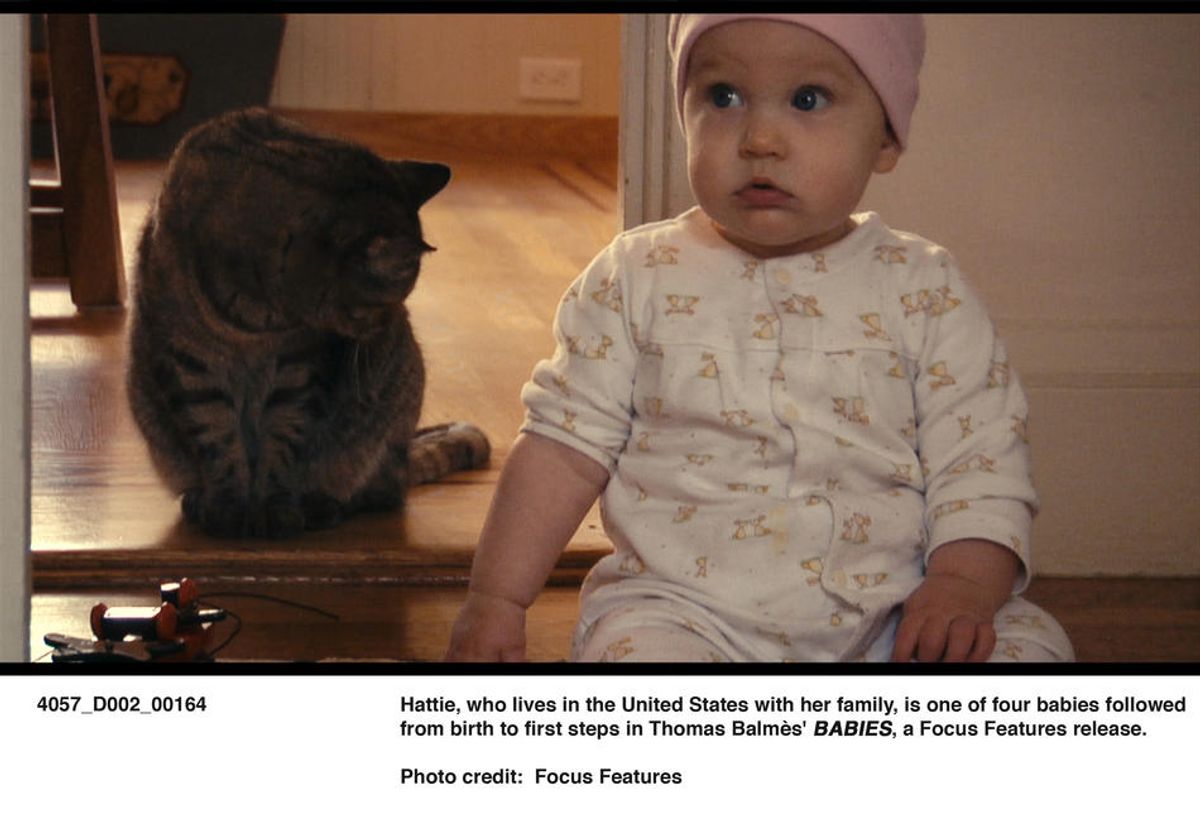

I don't think the movie's power owes to any message, either. Balmes has explained "Babies" as a One World parable whose intent is to transcend cultural and geographical barriers and show that people are people and babies are babies. The film follows four children: Mari, raised amid the vertical ice cube trays of Tokyo; Bayar, a rural Mongolian whose childhood pets include chickens and goats; Ponijao, a Namibian who grows up in a dusty, fly-strewn village; and Hattie, born to New Age yuppies in San Francisco. Their parents are loving but somewhat abstract presences, featured as their offspring might dimly perceive them, as sources of nourishment, shelter and comfort. Balmes achieves his kumbaya-flavored ambition and then some (though it should be said that after proudly proclaiming such an agenda, the director has some nerve chiding Hattie's parents for being crunchy liberals who keep a "No Hitting" book on their daughter's shelf). But even if Balmes' mission were a deep and urgent one, most moviegoers would dismiss it, rightly, as the cinematic version of a plate of boiled spinach.

It's not the message that matters. It's the filmmaking.

From Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock to Alex Gibney and Errol Morris, the predominant nonfiction film aesthetic is some version of go-go-go-and-never-let-up. It's montage-driven style that seeks to hold one's attention by any means necessary: a flurry of quick-cut images and busy graphics, title cards and stylish reenactments, narration and music (doom synth, pop tunes, Philip Glass). It's nonfiction filmmaking as Ed Sullivan-style plate spinning: razzle-dazzle.

Sometimes this style is dramatically appropriate -- and emotionally involving, and intellectually stimulating -- and sometimes it isn't. Either way it's a far cry from the lo-fi aesthetic of "Babies."

Balmes and his collaborators have gone against the grain of recent documentary film and reached back in time -- way back -- for inspiration. Like another current, sensationally effective, picture-and-sound-driven documentary by French filmmakers, "Disney's Oceans" -- a movie likewise dismissed as eye candy even by critics who enjoyed it -- Balmes has returned to the early years of motion pictures, a time when people were still thrilled by the very idea of cinema as a window that revealed other places, other lives.

"This is the most real documentary I've ever done, the closest I've ever gotten to pure documentary," Balmes told the New York Times. "Most documentaries are produced like feature films, and that kills [their] specificity. But with this one there was no voice-over, no script. It's just real life."

This kind of filmmaking is easier to describe than it is to do, and "Babies" is a fine example of how to do it. The movie asks the audience to sit in the dark and absorb not just the image of a particular baby but also the ambience of the living room or bedroom, country road or city street that serves as backdrop for moments in the baby's development. It then asks us to ponder the fact that these babies are less than a year old and strongly rooted in the specific daily experience of life in four very different parts of the world, yet we can already see their personalities not so much taking shape as emerging, like intricate sculptures that were buried in the soil a long time ago and are just now being unearthed.

Shares