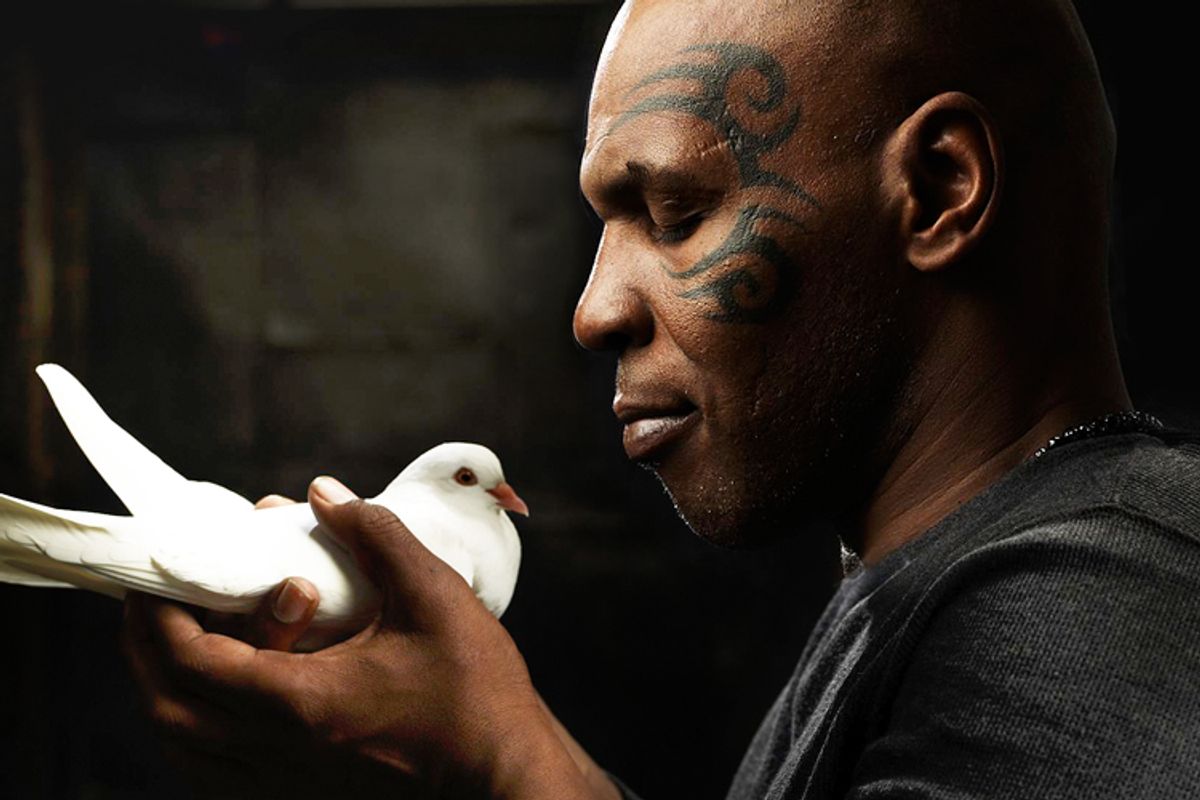

As we feast on the tabloid insanity of Charlie Sheen, we should keep Mike Tyson in mind. The former heavyweight champ is psychologically scarred and biographically scary: ex-mugger and home invader, convicted rapist, serial ear-biter. But six years after his retirement from boxing he's no longer a boogeyman, just a complicated, infuriating person whose biography humanizes his sins without excusing them. The pilot episode of the new Animal Planet documentary "Taking on Tyson" (Sunday, March 6, 10 p.m./9 Central), in which the former champ reconnects with his childhood as a pigeon tender and tries to make it as a professional pigeon racer, is one more step in the rehabilitation of his image. Watching it, there were moments when I wondered if we'd ever see a day when Sheen or Mel Gibson would straighten themselves out as Tyson has tried to do, and make the psychological struggle public without just seeming to exploit it. How is it possible that Tyson can play off his thug image in "Black and White" and "The Hangover," goof with Leonard Maltin in a "Funny or Die!" viral video and play Rock 'Em, Sock 'Em Robots with Jimmy Fallon without making audiences ill? Is it that he's put a few years between himself and his disgraces? Or is he just a more interesting person?

One thing's for sure: He's as much a performer as an athlete -- more so, post-boxing. When director James Toback lingers on his Maori-tattooed face in the great 2008 documentary "Tyson," he launches into monologues decorated with baroque adjectives and nouns ("skulduggery, "chastity," "decrepit," "heathen," "subservient") and sketches friends and foes with Dickensian flair (he calls Don King "a wretched, slimy, reptilian motherfucker"). He's charismatic in "Taking on Tyson" as well. But because it's a reality show rather than a one-on-one confessional documentary, we see a different side of Tyson -- less intense and poetic, more ordinary-seeming. He tells some of the same stories here as he did in the Toback film (his life is his life), but the tone is different -- less grandiose and self-obsessed, more casual. Somehow the lack of intensity brings a different sort of truth to the forefront. We get the sense that Tyson is further along in the rehabilitation process. He's discovering new things about himself, and being surprised by his discoveries.

For instance, there were powerful moments in "Tyson" when he talked about his mentor, trainer Cus D'Amato. Reporters once reflexively described D'Amato as the father figure a then-young Tyson desperately needed, and a "kindly" person whose death sent the boxer spiraling into depression and into the orbit of corrupt manipulator Don King, who fed his worst impulses and grew fat on his earnings. When Tyson spoke to Toback about D'Amato, his eyes filled with tears of rage as well as sorrow. As he praised D'Amato for awakening and focusing his lethal anger, you could see glimpses of the deprived, resentful Brownsville teenager, the son of a promiscuous drug addict mother and an absent father, a bullied boy who remade himself as a seemingly invincible bruiser.

But in "Taking on Tyson," the boxer talks about how D'Amato taught him to believe he was better than everyone else -- "smug" and "superior" and entitled to do as he pleased. He suggests D'Amato's attitude might have contributed to his downfall as much as anything that happenened to him in childhood. At 44, over a quarter-century after the death of the only dad he ever really knew, he seems to have stopped idealizing D'Amato, and begun to see him the way the public sees Mike Tyson: not as a hero, a villain or a fallen idol, but as a person. His tone is matter-of-fact, but there's a sense of surprise as he speaks, and at a couple of points he grins as he puts psychological pieces together and figures important things out.

In another intriguing moment, a camera crew follows Tyson back to Brownsville and watches him revisit the spot where he threw his first punch. We already heard this tale in "Tyson" and in other documentaries and news pieces -- the story of how some teens attacked Tyson while he was carrying a bag of live pigeons to his home, and how one of them snapped a pigeon's neck and tossed the carcass at Tyson. "He took my bird away, cracked it," he tells the camera crew. When he related the story to Toback, he was mournful and furious. When he tells it again in "Taking on Tyson" he's more detached, with a lighter tone -- almost as if he's describing an incident that happened to someone else.

Without being able to climb inside another person's head, it's hard to say exactly what any of this means, and it's likely that Tyson couldn't tell us, either. But the process of self-discovery is right upfront in "Taking on Tyson," and it's fascinating. The series shows the ex-champ seriously channeling his energy again, maybe for the first time since his release from prison, building a professional identity apart from boxing by funding a coop in Jersey City and entering a new sport as a glorified rookie.

I didn't know anything about professional pigeon racing going into this series. The logistics are fascinating -- the way that pigeons are bred, fed and trained to fly over great distances is similar to the way boxers train for a fight, and the corner team is just as important. Tyson seems to have hired a good bunch to take care of his birds: a cigar-chewing landlord named Mario Costa, an attentive and pleasant caretaker named Vinnie Torre, and a couple of brothers, Junie and Ricky Roman, who seem to have the same up-from-the-streets attitude as the young Tyson but fewer of the debilitating emotional issues. It's interesting to watch Tyson learn a new skill for the first time. I've seen him in a lot of public situations, but never one where he was put in an intellectually inferior position, having to sit there quietly while other people tell him how to do things or chastise him for not doing them right.

The pigeon training sequences are intercut with flashbacks to Tyson's childhood and career. At first, series director Karen Plumb seems to be pushing too hard to link Tyson's childhood love of the birds with his present tense struggle to reconnect with something pure and innocent. But it becomes clear that Tyson shares that interpretation, and it's probably why he decided to put the experience on camera and turn his success or failure into a public drama. (He's credited as the show's executive producer.) Except for the conspicuous omission of Tyson's rape conviction, every major moment of thug behavior is prominently mentioned in the pilot. Tyson and Plumb don't try to shade any of it or suggest that because Tyson is shown doting on birds, that means what's past is past and we should forget about it. "Taking on Tyson" catches a man in the act of trying to become someone else, someone better. Who is taking on Tyson? Tyson.

Shares