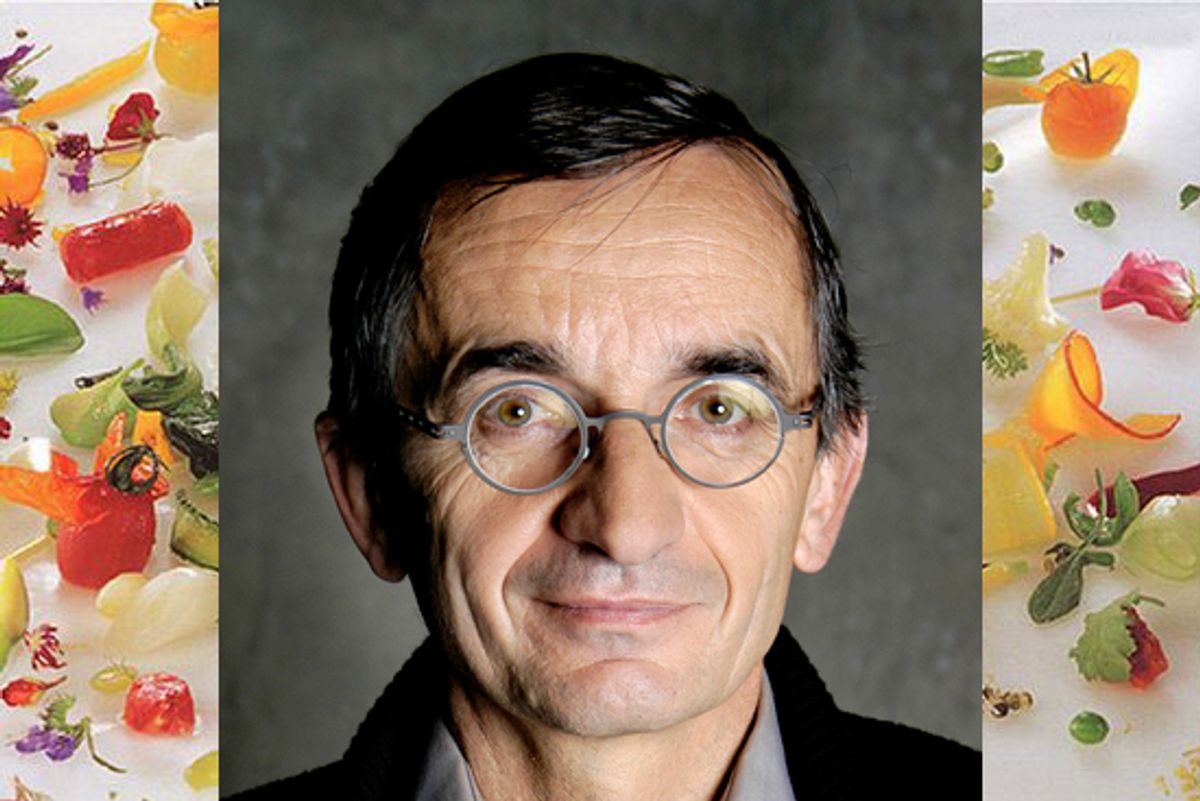

I have a new hero. I’ve never met him, never tasted his food, and even still, I am a worshiper at the altar of Michel Bras.

For years, Bras was to me just another name in the long list of French chefs who supposedly changed everything. I regarded him with a vague sense of respect, the kind you affect mainly because you know you’re supposed to. So out of professional obligation, I went to the French Institute/Alliance Française’s Crossing the Line Festival, where Bras gave a rare interview to go with a screening of "Inventing Cuisine: Michel Bras," a 10-year-old documentary on the creation of four of his dishes.

But from the title shot of the movie -- Bras spooning sauces onto a plate in tight lines and deliberate smears -- I was stunned. I recognized his swoops and dramatic arcs as signature plating styles of some of my favorite chefs today; I had no idea food could have looked like that a decade ago. I sat up.

Bras is known as kind of a vegetable savant, and so the film begins with him at the market before dawn, selecting, and soon we see him preparing them with his team.

Vegetable prep in every kitchen I’ve ever worked in is a chore, shit work, a task where you find satisfaction mainly in getting something done more quickly than you did it yesterday. It’s about powering your way through, leaving trails of carrot peels in your wake. So watching Bras work is stunning. He hones two short paring knives; he pulls on a glove; and for the next few shots we see him peel and trim with his head down. There’s a quality of dignity and purpose to his movements. He handles the vegetables with both hands; he handles them in his hands, not, in the manner of badass cooks, with a knife against the cutting board. He holds up a turnip and gently, swiftly, separates it from its skin. He works with one stalk of leek, one shell of peas at a time. Efficiency is not his priority; there is something greater.

"I try to relate to the produce, to communicate with it," he says. It’s the kind of statement that usually makes my eyes want to roll, the kind of thing people who think they’re elves say. But then he talks about how the vegetables change from day to day, and how he adjusts the dish: One day, a squash might be cooked a little more to highlight its tenderness; the next, it might come in a little firmer, so he cooks it less to give the dish more texture. When you see him handle that turnip, peering at it from behind wire-rimmed glasses, he convinces you that it’s not about goofy spirituality but about care and respect and mastery.

I’m interested in mastery as much as I am in cooking. When a master takes his or her tools out, when they stack their unceremonious crates of ingredients, I am transfixed. In part I try to see if I can make sense of what they’re doing or what lies ahead, and in part I just take in how they move, the mannerisms of hands and bodies. Is there something to them? Something that speaks of how they do what they do? Are their movements fluid or sharp? Smooth or jarring? Confident? Powerful?

There’s a scene later in the film where Bras cooks a dish he calls "Shadows and Light," for the way the dense obscurity of black olives and the shiny, almost liquid whiteness of just-cooked monkfish look against one another. The technique he uses is a classic but involved one, where he sets the fish in a puddle of hot oil and bastes it constantly, heating it from above and below. He adds danger to the technique by using oil blended with black olives -- it gives him flavor and stains the outside of the fish, but, because of the sediment, threatens to burn at every moment. The shot is mesmerizing. He cooks cleanly, keeping the oil moving so it doesn’t scorch at the bottom of the pan, scraping the liquid in quick, gathering strokes and sweeping it up into the spoon. His hand quickens, raining hot, olivey fat on the fish and dipping back into the pan in fluid, graceful circles. The oil bubbles impatiently; the burning feels imminent, but Bras is unhurried, his actions deliberate. He prods the fish with his spoon, feeling the resistance. He takes it out and cuts it. It’s perfect.

In a world where the word "locavore" exists, it can be a cliché to say that a chef is inspired by a sense of place. But Bras speaks of his inspiration in terms beyond who his farmers are and the dirt they work. "Shadows and Light" is an attempt to express the experience of watching the sun and clouds play on his valley. The idea sat with him for years before it occurred to him to pair inky olives and pearlescent fish. In the film, he sits on a rock, where he observes the light, talking about his fascination with monkfish, how it cooks to a quality of translucence. He tries to connect the dots between his inspiration and how he realized his vision, but is frustrated. He balls his hands into little fists, like a boy who can’t find his words. Finally, he finds the thought that eluded him: that this dish, focused so literally on showing the visual qualities of shadow and light that inspired him, is still fundamentally symbolic. It speaks of his love and fascination with his land, and yet to express that, he ironically uses monkfish and olives -- ingredients not of that land. It’s a dish of abstraction, not representation.

And yet, his cuisine can also be pointedly direct. "One day, I was running," he said during the interview. "It was a dark day, a low sky. I came around a bend, and a smell provoked me, impressed me, almost scared me. Almonds, honey -- like an old woman. It was an herb, Queen-of-the-Meadow. How was this herb going to inspire me? That’s my relationship with the world around me." It’s a sense of wonder that guides him, a sense that there is always something more to be found in what you already know.

And yet, what finally canonized Bras for me was his silverware. His is a Michelin three-star restaurant, a recipient of the highest honor of France’s most esteemed culinary guide, which is to say that it is fancy. And so guests are confused when, between courses, servers float by and take away the dishes and used silverware, leaving their dirty knives. But Bras is from Laguiole, home of the famous knives of that name, and where the custom is for children to receive a knife from their parents when they become adults, one that they are to keep forever. And so Bras asks his guests to keep their knives throughout their time with him. "I don’t call it my restaurant," he said. "It is my place. You are at our home."

For this grand cuisinier, cuisine is not about the ego on the plate. It’s about genius and creativity and craft, but also about humility, also about understanding and sharing, about bringing people together.

A man in the interview audience stood up. He asked Bras a question, pointing to his innovative technique, about being a father of avant garde cuisine. Bras took in the translation and smiled nervously. He demurred. "I love my work," he said, "because I am in the business of happiness." And then he disappeared, coming back a moment later with a few sheets of paper.

They were letters he received from a guest, a woman with a husband who’d been hurt in an accident, a paraplegic. They were young and loved food, and they used to plan their trips around special meals. In the hospital, they talked about going to Michel Bras as soon as he was well enough to, and so they finally went. She wrote to Bras afterward: "Thank you, so much, for our several hours of perfection."

Two years later, she wrote him another letter: Her husband could walk again. They have a child. And she wanted to share this news with him, because of that dinner they had in his place. "That," Bras said, "was a great moment in my life."

Shares