The news reaches me silently.

"Manizi lawyer and PUDEMO stalwart Dominic Mngomezulu is dead after a long illness."

I am stunned. The news comes as I am preparing to leave to report on the 13th International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa. I type the name of my old friend into a search engine to find a recent contact number for him. I'd hoped to visit him in neighboring Swaziland, a country where I'd taught high school 11 years earlier, after the conference. Instead, this brief article from a Swaziland newspaper appears at the top of the screen, announcing his death two years earlier. No cause is listed.

In shock, I e-mail Brenda, a Canadian friend who still lives in Swaziland. Her reply comes swiftly: Yes, she had heard of his death. So sad; it was AIDS.

But how was this possible? He was straight, highly educated, more enthralled with politics than women. Then I do a Web search on AIDS in Swaziland, and a whole new reality of a country I thought I knew comes up on the screen.

Swaziland is one of the countries worst affected by AIDS in the world. As many as one-third of its young adults are infected. And the rate of infection is rising with depressing speed: From 1997 to 1999 alone it jumped from 26 to 32 percent. Life expectancy has dropped more by than 13 years since 1992, and is now at a low of 47. Three out of every four Swazi deaths are from AIDS. And according to UNICEF, over the next decade and a half, as many as 40,000 Swazis will die each year of AIDS. This gentle country of fewer than a million inhabitants was crumbling.

The next week I'm attending the AIDS conference, whose slogan is "Break the Silence," and I learn more about the dire situation in southern Africa. Two-thirds of the world's more than 40 million AIDS cases are in Africa, most of those in the sub-Sahara. Sixteen thousand Africans are infected with HIV each day. One in 10 African children is an AIDS orphan, and many of them will end up dying of AIDS themselves. And if this sounds bad, the conference presenters repeatedly emphasize, wait a year or two, or God forbid 10, because things are only going to get worse.

The numbers overwhelm me. They are almost impossible to comprehend. But the news of Dominic's death gives some small, personal meaning to this horrendous loss of human life and potential. I keep him in my mind while I'm doing the math.

Then halfway through the conference something strange happens. Brenda reaches me again, this time by phone. She tells me she has good news about Dominic. My heart races. Perhaps the article was a mistake; perhaps he is still alive ...

"He didn't die of AIDS," Brenda tells me excitedly as I catch my breath. "Yesterday I bumped into a friend who knew him quite well and who told me he died of sugar diabetes. Undiagnosed."

Brenda pauses. "So that's good news, isn't it?"

For a moment I can't answer. Good news? He's still dead. But Brenda seems to think so, albeit hesitantly. I can hardly blame her. Who, after all, would choose AIDS as a way to die? But the relief in her voice isn't just because Dominic avoided an especially cruel illness, I think. It's because more than 15 years into the epidemic, AIDS is still the most shameful thing on earth to die of.

I'll go back to Swaziland, I decide. After only a few days at the conference, I'm already tired of hearing about the devastation. I'm tired of learning more atrocious statistics that I can't possibly comprehend. I need to see the effects of AIDS for myself and in a place I knew before AIDS strangled its people in a deadly grip. And, I realize, I need to find Dominic's children. He was the sole breadwinner for his large, extended family and they undoubtedly need some financial help. If, as was discussed so much at the conference, we all need to do something now, his children are the place to start for me.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My friend Brenda picks me up at the airport. We head into the rural expanse of the north, the shrubby hills gradually leveling off to a steady, swaying sea of sugar cane. Swaziland is a nation slightly smaller than New Jersey, surrounded by Mozambique to the north and South Africa everywhere else. It's a conservative country that takes its traditions very seriously. One of the worst insults a Swazi can make is to accuse another of "un-Swazi" behavior. Polygamy is perhaps its most sacred tradition and is still widely practiced. Swaziland is also one of the few remaining monarchies in Africa, and King Mswati III, barely in his 30s, has just named his eighth wife. His father, King Sobhuza II, had 80 wives by the time he died and fathered more than 100 children.

My friend Dominic was a charming mixture of Swazi tradition and astute political awareness. He was raised, like all other rural Swazi children, on a homestead with several mothers and dozens of siblings. But he was also committed to bringing change to his country. He and a small group of friends formed the core of the democratic movement in Swaziland, and most of his adult life was dedicated to the struggle.

As we drive, Brenda tells me that she has arranged a meeting tomorrow with a relative of Dominic's who knows the whereabouts of all his children. Not only that, Brenda says, but this relative also has some intriguing news about his death.

When I lived in Swaziland 11 years ago, AIDS was a joke. Literally. It went like this: What does AIDS stand for? As you tried to recall what each letter stood for -- this was before acquired immune deficiency syndrome rolled so easily off the tongue -- the punch line came: American Instigation to Discourage Sex.

Now a spoiled sex life is the least of the country's concerns.

On my first morning there, I peer at two pages of obituaries that fill the local newspaper. The notices quaintly and evasively refer to the passing away of a whole generation of young Swazis: Friends and relatives of Roda Betfusile Magagula are notified that she is late. Night vigil on Friday. Friends and relatives of Mlungisi Makama of Ngwenya village are notified of his death after a short illness. He will be laid to rest on Saturday at 7 a.m. A night vigil will be on Friday. Relatives and friends of the Maziya family at Zandondo are notified that Sibusiso Maziya is late.

It's a language composed of code words. Sudden death. Short illness. Late. All meaning the same thing. All the notices are accompanied by photos of mostly young people in their 20s and 30s, even some children.

We head through the cane fields to church, with the pungent, too-sweet smell from the sugar mill in the distance reaching our nostrils. As we pull up outside the company garage that serves as the church, the parking lot is deserted. Inside, fewer than a dozen worshippers stand swaying and singing. I look to Brenda, questioningly.

"Yeah," she acknowledges, in an embarrassed, hushed tone. "Everybody's away at funerals on the weekends. It's hard to keep the church going."

After the service, we stroll through the town, passing hardly a soul. When I lived here a decade ago, the roads were lined with families in their Sunday best streaming to and from church.

Now Swazis spend weekends on their homesteads burying their dead.

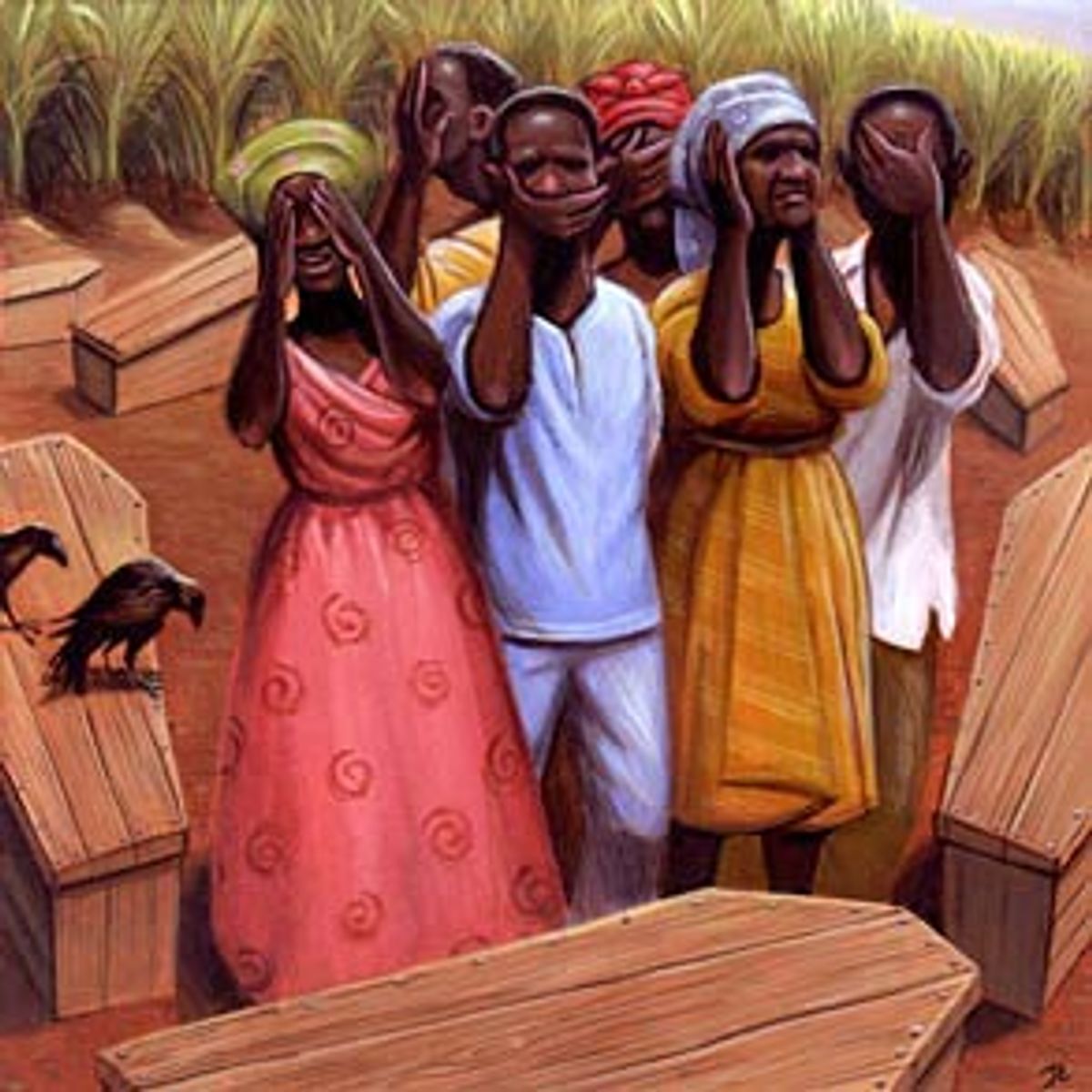

Hundreds of funerals are held each weekend across the country. They used to be held during the week, says Brenda, but there were simply too many and people couldn't afford any more time off work. So now Swazis spend almost every weekend at funerals. Sometimes, Brenda tells me, you can hear the soulful wail of the mourners drifting over the sugar cane fields at sunrise. Swaziland has entered an endless season of mourning.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Later in the day, on the veranda of a local clubhouse, we sip soft drinks while waiting for Margaret, one of Dominic's relatives. (I've changed some of the names in this story to protect her and Dominic's other loved ones.)

"Shame!" she exclaims, the southern African catchall word for sympathy, before she wraps her arms around me. A large, slightly disheveled woman with a maternal glow, she looks to be in her mid-40s, but may well be 10 years younger, because of a lifetime of overwork. She holds me and we cry together for a few minutes. Then, grasping firmly onto my hand, she pulls me into a chair and we get down to the business of Dominic's children. But first, she has some news about his death. She shakes her head and tsks in typical Swazi fashion.

"Haye, it was so sad," she begins. "You know, he was poisoned."

"What?"

Margaret pauses dramatically and grips my arm.

"Haye! You see, this is the kind of country we live in."

"But what do you mean? I thought he died of diabetes ..."

"He fell ill and went to the hospital with that. But, you see, he was sent to a government hospital, and they realized they could get him finally. The government used the opportunity to poison him."

I sit there, dazed. It sounds so conspiratorial, yet it was possible. Dominic had been jailed and others had been tortured. I ask Margaret if there was any proof. She says she heard an independent doctor had conducted a separate autopsy and found signs of poisoning. Also, a team "from outside" was called in to investigate the possibility. Yet, when I press her for details, her answers grow vague. She will find out more, she promises, and write me with the information.

Margaret is only slightly less equivocal when it comes to Dominic's children. She is pretty sure he had five or six. Five or six! Three years ago he'd told me about two. How could this be? She counts them out on her fingers: two in South Africa and four in Swaziland living with various relatives. One of his children, she says, a young boy, is living in dire conditions. He surely could use some help. Again, she will find out more and write me with all their names and particulars.

When we later visit Margaret's home -- a squat cinder-block structure with a corrugated-iron roof -- a toddler in a scrap of a white dress rounds the corner into view. I ask Margaret if the child is hers.

"No, I brought this child here yesterday. Her parents are not right," she says, without further explanation.

The care of children is fluid in Swaziland; they pass casually among the arms of an extended family, flowing with the currents of need and capacity to care for them.

"I don't think she was getting enough to eat," Margaret adds. She reaches down and lifts the girl's dress, revealing a tummy bloated from malnutrition.

"How long will you keep her?" I ask.

"Well, I told her parents that I would just take her for a few days," Margaret confides. "But I think, really, I will be keeping this child."

The next day, a sunny Monday morning, a handful of people lie on the front lawn of a sugar cane company medical center, strewn like broken branches after a windstorm: women with babies suckling at their breasts, men with the shingles scars -- an AIDS "marker" -- glistening on their shoulders and necks. Too exhausted to stand, they lie here waiting to see the doctor.

I, too, am here to see the doctor, to ask him about the AIDS epidemic in Swaziland. He agrees to meet me only if I promise not to identify him. If his name is linked to any story on AIDS in Swaziland he could lose his job, he tells me.

His fear is justified. Less than two years ago, a small, successful appliance manufacturer called Fridge Master discovered just how explosive breaking the AIDS silence could be. The company was a major success story for the government's efforts to bring in foreign investment. Then, in 1998, the Swazi government learned of "mysterious deaths" among more than 1,000 of the firm's workers. Swazi members of Parliament instructed the labor minister to investigate rumored "lethal chemicals," which allegedly were the cause of the deaths. In response, the company proclaimed its safety standards and explained that the workers had died of AIDS.

Fridge Master couldn't have been less prepared for the uproar that ensued. Its workers suddenly found themselves shunned by local women and began to be denied credit in stores. The workers then demanded a retraction and apology from Fridge Master. The press, Parliament and labor organizations joined in, accusing the company of "cultural insensitivity." Workers staged a three-day strike. Shortly afterward, Fridge Master announced it would move a planned factory expansion to Botswana because of Swaziland's "head-in-the-sand denial of AIDS."

This doctor isn't going to risk bringing that kind of backlash upon his employer.

Our interview is brief and tense. The only point at which he expresses any personal opinion is when I ask him about HIV testing. He tells me he thinks patients should be tested even without giving their consent. His view surprises me. At the AIDS conference, I learned that HIV testing without consent not only is a human rights violation but is also far less effective in preventing the spread of the virus than testing with consent followed by counseling.

But I understand his frustration. Hundreds of sick people are coming to him, but refusing to be tested for fear of the result. The lack of testing and even of a standardized system of reporting cases has led to disparities in estimates of infection even by various international bodies. In March 1999, for instance, UNICEF reported that 31 percent of all Swazis were HIV positive. It went on to project that up to 40,000 Swazis would die yearly of AIDS over the next 15 years, while estimates of UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) and the World Health Organization were lower. The disparity allowed the government to hotly contest the UNICEF predictions. UNICEF's attempt to wake up Swaziland to the epidemic raging through its land was effectively derailed, and the subsequent debate focused on whose numbers to trust, not on what should be done.

When testing has been done, however, results are chilling. One 1998 study showed that roughly half of all patients admitted to Swazi hospitals were HIV positive. Another study looking at HIV in pregnant women found that, in 1992, 4 percent of Swazi women were infected with the virus. Six years later, 32 percent were infected.

Swazi reaction to the epidemic has been painfully slow. This spring, the king finally pronounced AIDS a national disaster and the prime minister inaugurated a crisis team to deal with the problem. But the quality of discussion around AIDS is disturbing. Last year, for instance, a Swazi royal and member of Parliament recommended branding or tattooing infected individuals and quarantining those infected. Moreover, Ben Dlamini, head of the government School Exams Council and a weekly newspaper columnist, insisted that AIDS had been sent by vengeful ancestral spirits angered by promiscuous sex. In one Swazi newspaper report, I read of M.P.s jovially expressing their distaste for condoms, saying it made them lose their interest in sex.

I am curious about condom use in Swaziland. Nicole Frazer, a Swaziland AIDS researcher who was also at the Durban conference, told me a little about condom distribution here. She said free condoms have been distributed in waves through the country, but they rarely reach rural areas. And Swaziland has plans to promote condoms later this year, but it lacks a national plan that would reach everyone affected by the disease. At the moment, she said, plans are being made and there are promises of big money from various organizations, but government funding has been far from sufficient. In the southern region of Shiselweni, however, one group has begun to hand out condoms at cattle-dipping tanks and hair salons to reach the many young people who are too poor to attend school.

I ask Brenda to stop at a pharmacy so I can see for myself what's available. I'm especially interested in the female condom, which was hailed at the AIDS conference as the future of prevention in Africa. African men do not want to wear condoms, I heard again and again from African AIDS workers. So now health workers are placing their hopes on providing women with a condom of their own, whose use they can control.

Outside the cluster of stores, a band of small boys in rags loiters by some shopping carts. They reach out their hands, begging as we pass. A decade ago, a Swazi child begging in the streets was unheard of. With the vast network of extended families, needy children were taken in. Now there are street kids in every large town, Brenda tells me, and for the first time ever, there are orphanages in Swaziland.

Inside the drugstore, I approach the pharmacist and ask her about female condoms. She tells me she has heard of them but doesn't stock them. Perhaps the supermarket might sell them. At the supermarket, I ask for the manager. He, too, tells me there are none in stock but that he hopes to get them sometime this year. He directs me to a rack of male condoms behind a counter in the far corner of the store. They keep them out of site, he explains, because customers are too embarrassed by having them on the shelves.

I wonder what kind of impact the female condom will have whenever it gets here. I recall the angry voices of African women at the AIDS conference: How do you talk about condoms, they demanded, when polygamy still exists? When sex is not negotiated, but taken for granted? When girls and women are coerced into relationships? When the legal concept of rape within marriage doesn't exist? When little girls are routinely violated because of a widespread myth that a man can be cured of AIDS by having sex with a virgin? To talk about safe sex is a joke, said one bitter activist, when women have no power.

In the afternoon, we visit an elementary school. A nurse from our health clinic visit earlier in the day asked to me to help her give a sex education talk to a class of 11-year-olds, in particular to talk about what I'd learned at the AIDS conference. At the beginning of the presentation, I write the word AIDS in bold on the blackboard and ask the students if they know what it stands for. They all raise their hands. I then ask them if they talk about AIDS at home and, if so, what have they learned. The students squirm uncomfortably. One girl at the back tentatively raises her hand. "My grandmother tells me not to go with boys because if I do I could die."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I'd almost given up trying to locate Conrad (not his real name), Dominic's housemate from 11 years ago. But on my last day in Swaziland, I find the number for his law firm and call. Miraculously, he is just on his way to a town we have to pass through on our way to the airport. We arrange to meet for lunch in an hour's time.

Over lunch, we catch up. He is now a wealthy man by Swazi standards. He owns cattle and is busy setting up a homestead. He has also become the father of six children by four mothers. "You've been busy," I joke, and he lets out a gentle, guttural laugh.

But it isn't all good news. Two of his children's mothers died recently and he's having trouble finding a family member to look after them. There are so many orphans now.

Our talk turns to Dominic and his children. Conrad says he's pretty sure Dominic had six children with four different women. Like Margaret, he believes two are living in South Africa. The others are being looked after by family members. He promises to write with their addresses.

Satisfied that I will locate at least most of Dominic's children, I broach the subject of Dominic's death. What began as a search for his kids, I realize, is now a personal inquest into his death. I mention the poisoning theory. Yes, Conrad nods, that was a real possibility. Dominic entered the hospital with pneumonia and died very quickly, leading many to suspect murder. Pneumonia? Was he sure? Yes, he saw the death certificate.

I sit in silence, wrapping my mind around this latest cause of death.

"So many people are dying," says Conrad at last.

"Of AIDS?"

"Of all different things," he replies, in a tense, stubborn tone of voice.

"You mean accidents or illnesses?"

"Of different things."

"Like what?"

Conrad is quiet. Then he says, "All I know is that since Dominic's death, too many people have passed away."

"Conrad," I say. "You're talking about AIDS, aren't you?"

Silence.

"It's AIDS, isn't it?" I repeat. "Why don't you just say it? We've been sitting here for over an hour talking about all these people dying, and you haven't said the word once."

"Break the Silence," the conference slogan that I'd found trite, suddenly hits me. It's not an easy thing to do.

Brenda speaks up nervously. "Megan, it's a small country and people are afraid that what they say will come back to haunt them. It might get around that Conrad is saying people are dying of AIDS."

Conrad nods. "That's right."

"But Dominic died of AIDS, didn't he?" I persist.

Another obstinate pause. "I don't know."

"OK," I say, finally. "You don't know. But that's what you think, isn't it?"

Conrad casts me a forlorn, helpless look. "Yes, that's what I think."

Only then does it dawn on me that Conrad's resistance to saying the word "AIDS," that the evasive look in his eyes, doesn't contain just shame and sorrow but fear as well. He is scared for his own life.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I reach Radley (not his real name), another of Dominic's friends, by phone the day I fly out of Swaziland. We arrange to meet at the Johannesburg airport, where I have a stopover.

Radley has been living in the South African city with his wife and two children since the early 1990s, when he was exiled from Swaziland for his political activities. The most sophisticated of Dominic's friends, he taught sociology at the university for years. We have little time, so I immediately ask him about Dominic's death. I don't know why, perhaps it's a necessary part of mourning, but I need to know with certainty what took his life.

I mention the poisoning theory. Radley sits still, quietly assessing me. Then he says it: Dominic wasn't poisoned. The doctor who cared for him when he died was a political ally and a friend. He told a small group of Dominic's closest friends -- after Dominic's death -- that he had been HIV positive. Dominic died of AIDS; there is no doubt. Ray's words are firm, but he looks sorry he has had to tell me.

So here it is: the truth I'd known all along. I've been just as much a player in the Swazi denial game as Dominic's friends and family. Part of me, too, didn't want Dominic to have died of AIDS. The part that wasn't ready to have my own stereotypes of who dies of AIDS -- gay men, drug addicts, poor, uneducated, marginalized Africans -- shaken to the core.

Still, I wrestle with the knowledge. I need some more explanation; I need to understand this better. Dominic wasn't a womanizer, I hear myself insisting to Radley. He wasn't a polygamist. He was educated, he knew better.

"Even the progressives, even the ones opposed to polygamy, practice it in some form," Radley explains, almost apologetically. "It's culturally acceptable. In fact, a man with many women is seen as hot, a stud. And the women have to some extent submitted to this culture. They'll go into a relationship knowing the man has other relationships or is even married."

But something has to change, I flounder. Everyone is dying ...

Radley shrugs. "The stigma is still so strong," he says. "Nobody owns up to being infected, and unless you have a massive education campaign, unless you change the way people actually live, nothing will change."

Will Swaziland be capable of this change? Or will it instead continue to cling to a tradition, to a quaint, coy silence that is wiping out a generation? Which will be the final teacher: change or death?

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I arrive back home the next morning. Compulsively, I head for the computer, sit down and punch Swaziland plus AIDS into the search engine. A brief Associated Press article appears with the headline "Miniskirts Banned in Fight Against AIDS."

"Swaziland will ban miniskirts in schools to try to halt the spread of AIDS, a government official said yesterday. The aim is to put a stop to sexual relations between teachers and their pupils in a country where at least one quarter of the population is infected with HIV. School girls are widely blamed with enticing teachers with their short skirts."

So here is the latest step Swazi leaders are taking against the worst threat the country has ever faced. Banning miniskirts and blaming schoolgirls. If it weren't so cruelly inept, it would be funny.

But this bit of news is nothing but a horrifying confirmation of the lessons gleaned from my brief odyssey. HIV has resulted in the worst disaster Africa has ever faced. But in the tiny, gracious nation of Swaziland, breathtaking silence and blinding patriarchy are still its most deadly agents.

Shares