As word leaked out last week that the New York Times had cancelled Abe Rosenthal's weekly op-ed column, people were trying to figure out what exactly had happened: Was he retiring? Or was he sacked?

Ever the editor, the 55-year Times veteran has something to say about it himself. "I have refused to allow any use of the word 'retired,' because I already retired and it would imply volition to me," he said from his home office in New York on Friday. "So we just said I 'left' in a very nice way. One retirement a lifetime is enough."

The 77-year-old Rosenthal, the epic and legendary czar of the Times, served as top editor there from 1969 to 1986. He helped remake and modernize the paper during those turbulent years (bringing it from two sections to four, for instance) but also earned the enmity of some who thought him cantankerous and overbearing. He wrote his column for 13 years; with its end came a surprising outpouring of admiration and affection, some of it from people he doesn't even know.

"It has buoyed me," he says of the response, with obvious emotion. "It's hard to describe but I feel as if I'm soaking in a wonderful hot bath of affection. I have received very warm, lovely e-mail from foreign correspondents and other correspondents, staff members in New York and around the country. It just keeps coming in. It makes me very happy. And I've heard from I don't know how many readers. I'm moved by them very much, not only by what they say but by the trouble they took to write them."

By his own account, Rosenthal needed some buoying. "There were a few days -- a couple of weeks maybe, knowing about it beforehand -- when I was in considerable depression. Not clinical but depressed. And it took me time to pull out of it and I believe I have." The fan mail helped, as did most of the editorial comment -- though he objected to a New York Observer editorial that said he had trouble with former Times publisher Arthur "Punch" Sulzberger.

"Punch Sulzberger was one of the nicest and best men I've ever met, and probably the best publisher in modern American history," he says. "He and I got along beautifully.

"It was because we both had the same concept of the New York Times," he said. "He didn't have to have long discussions. We knew what we wanted and what we didn't want. We wanted to expand the paper, make it more interesting to more people but also keep its character. And we could almost look at each other and know what we were thinking."

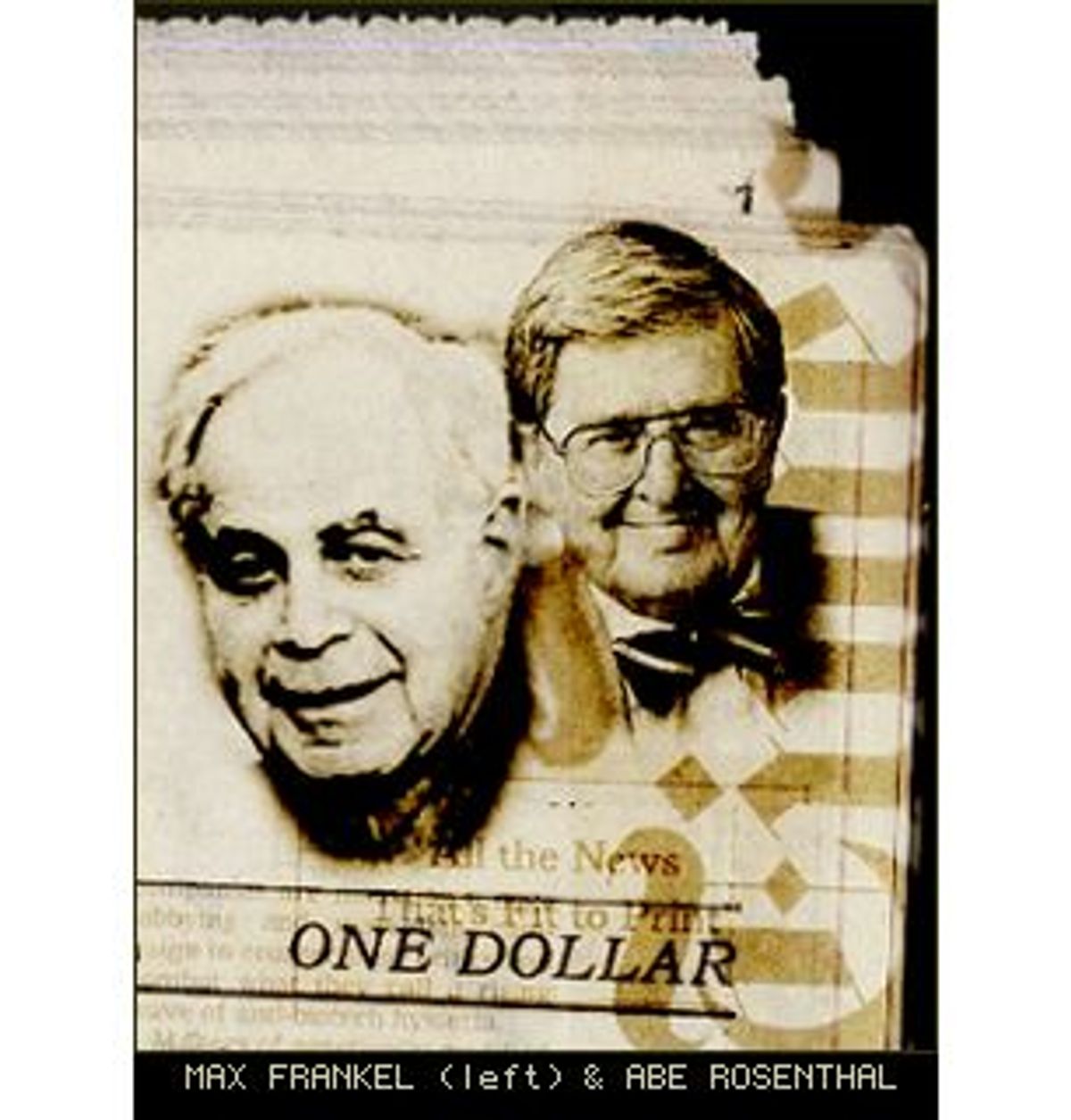

Of Punch's son and the paper's current publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., he declines comment. And an article in the December Vanity Fair is something else he'd rather not discuss -- though it's getting quite a bit of attention among the staff of the New York Times. David Margolick's media piece, "Clash of the Times Men," is a hair-raising and invective-laden recounting of the feud between Rosenthal and his successor as the paper's top editor, Max Frankel. And it hit the newsstands less than a week after Rosenthal left the offices on 43rd Street.

In journalism as in comedy, timing is everything. Margolick (who reported on the law for the Times for 12 years and is now a contributing editor at Vanity Fair) was essentially following up on the story that had been simmering all year. Frankel, who led the Times from 1986 to 1994, savaged his predecessor in his memoirs, "The Times of My Life and My Life at the Times," published earlier this year. He portrayed him as alternately self-promoting and self-pitying, small-minded and grandiose, and stated his sole goal as executive editor to be the "not-Abe."

Rosenthal was uncharacteristically slow to respond -- at first. But in interviews in Israeli papers (Ha'aretz and the Jerusalem Post) this spring, Rosenthal confessed to looking at his rival's book long enough to throw it in the trash.

"I'm a city boy and I know enough that when I walk along and I see a dog shitting in the street, not to stop and examine his dung," he told the Post. "I just walk on and forget his existence."

As if. In Vanity Fair, Rosenthal gilded the turd, calling Frankel a "coward," "somewhat of a liar" and "a bit of a fool." He blamed Frankel for missing the Watergate story and criticized his editing of the Sunday paper. Other than that I guess he liked him fine.

Rosenthal regrets having responded to questions about Frankel's book and is reluctant to talk about Margolick's article, either. "You see what is happening here is somebody wrote a book and that book was unpleasant and unpleasant things are constantly being commented on and I'm constantly being asked to comment on a rather despicable book," he says. "I don't like having my career, which is not at an end, being linked to this. I can't help it, but I certainly have no intention of dignifying it or anything. I've had it with this."

By his own admission, it's hard for him to stop. "I'm a garrulous -- garrulous isn't a word I like but I talk a lot to newspaper people ... I'm a newspaper man. But at some point it gets purely ridiculous. To go on talking about a book I don't like and a magazine piece which I dislike -- but I'm not accusing him of anything. So why go on talking about it?"

Because people keep asking, thanks to the confluence of events. On Nov. 5, the Times published Rosenthal's last op-ed contribution, under the slightly pathetic headline "Please Read This Column!" That had been the title of his first effort in the spot, published Jan. 6, 1987. The gesture was meant to imply some closure.

He wrote of his storied career at the paper, from his humble beginnings as a stringer from City College through his assignments covering the police beat to the United Nations, Poland (for which he won a Pulitzer) to Asia. As executive editor he was credited with bringing verve to the paper's sometimes stodgy reporting, and was at the helm when the Times (over the advice of its attorneys) decided to publish the Pentagon Papers. Susan Tifft and Alex Jones' "The Trust," a lively account of the family behind the paper, gives most of the credit to then-publisher Punch Sulzberger, and Frankel accuses Rosenthal of shaking in his booties, but the fact remains: Rosenthal was ready to quit if the paper balked.

On that same day, on the opposite page, an unsigned editorial gave him the gold-watch treatment, celebrating his accomplishments and wishing him well. Yet the Times' chief rival, the Washington Post, had something to say as well. Howard Kurtz's media column had Rosenthal complaining of his treatment in is-this-how-they-repay-me? tones. Caught while cleaning out his desk, the 56-year veteran of the Times was not going quietly -- and he made it clear it wasn't his idea. Publisher Sulzberger had told Rosenthal "'it was time.' What that means, I don't know ... I didn't expect it at all."

Rosenthal still insists he didn't see the ax coming. "I knew when we cut back [the column to once a week from twice] we would talk about it someday in the future and have a discussion but I thought we would have a discussion." Here he laughed. "I was not ready for it."

But he acknowledged that he served at the publisher's pleasure. "I never had a contract with the New York Times in 55 years," Rosenthal said. "Never occurred to me. Even if they had offered it I would have been insulted, I guess."

Did the Margolick story in Vanity Fair in any way precipitate Rosenthal's forced departure (as the New York Post suggested)? Though the piece hadn't been published yet (it hit the newsstands in New York Thursday), many Times staffers had been contacted by the writer and quite a few were quoted on the record. At an institution that has traditionally valued appearances, such a public airing of dirty laundry was bound to prove embarrassing. The publication of the Tifft-Jones book had already brought tsuris to some family members (the authors are as candid about various extramarital affairs as they are about the paper's editorial turmoil). Could more bad press -- specifically Rosenthal's unkind assessments of Frankel (currently a columnist for the Times magazine) have tipped the scales?

The author thinks not. "He had already spoken out to a limited degree in the Israeli newspapers," Margolick told me. "I think this must have been part of their long-range thinking. I guess every reporter likes to feel that he's affected events but it would be unduly self-aggrandizing in this case for me to feel that way. I really don't think this has played any role. The larger story is that Arthur is asserting his authority more aggressively and putting his stamp on the paper," he continued. "And that transcends the situation with Abe. That's the larger story and we can expect more of that kind of thing."

And as Margolick intimates politely in his piece, Rosenthal's column was hard to defend. Blustery, alternately vague and erudite, "On My Mind" (as it was called) was mocked immediately for its meandering guess-what-I'm-writing-about style (Spy parodied it as "Out of My Mind"), but the column was a bastion of conservatism on the largely liberal-leaning editorial pages.

Somewhere along the line, though, Rosenthal became a champion of oppressed peoples in other parts of the world. Persecuted Chinese Christians and genitally mutilated African women all became subjects of his concern and compassion. (Arabs in Israel were a little trickier; he went through some moral contortions in trying to reconcile the state's treatment of both Palestinians and Jewish settlers with his ardent Zionism.)

Some detractors have argued this was merely intellectual sentimentality, to make up for his more intolerant stances as executive editor. Under his watch, gay and women's issues were given short shrift. The paper was slow to cover the AIDS epidemic, gay reporters remained largely in the closet, and the words "gay" and "Ms." were not allowed in Rosenthal's Times.

But the portrait of him that emerges in Margolick's story is a relatively warm one. As an editor he was often able to overcome his prejudices. A fiercely anti-communist conservative, he nevertheless pushed for the publication of the Pentagon Papers and was outraged by the U.S. government's cozy relationship with right-wing dictators. (He also coined what even Frankel conceded was a "memorably succinct" description of the paper's conflict-of-interest policy: "I don't care if you fuck elephants as long as you're not covering the circus.")

Rosenthal is, after all, 77 years old. Russell Baker recently departed those pages as well and it's possible that Sulzberger (as well as editorial editor Howell Raines and executive editor Joe Lelyveld) might have just wanted some fresh blood. "You've got to be really good to do a column and you have to be really good to not go on automatic pilot," one veteran Times editor told me. (No one who I spoke to at the Times wished to be quoted by name.) Rosenthal's column had been reduced, over the years, from twice to once a week and a lot of readers may have wished the paper had dropped the hammer sooner.

"The shelf-life of a columnist is much shorter than it used to be," said Margolick. "People don't want to listen to the same voices as long as they once did. The culture has changed. The era of Arthur Krock and James Reston is over. And the turnover is going to be a lot quicker than it used to be."

It is doubtful anyone will enjoy the sort of latitude Abe Rosenthal did. Even writing a single column a week, he made his presence known on the 10th floor of the Times building in a variety of ways, including controlling the thermostat so that the rest of the staff sweltered or froze in rhythm with his body heat. But such eccentricities are small beer compared to his legacy. As the Times' R.W. Apple Jr. told Margolick, "Rosenthal was not the nicest man to work for but -- and there's a major but -- he may have saved the New York Times."

The paper is clearly undergoing some changes; shifts on the editorial pages may simply be part of a larger trend. Earlier this week the Times announced it had hired Paul Krugman, an economics professor at MIT and former Slate columnist, to write a regular op-ed column. And Metro columnist Clyde Haberman was pegged by the Washington Post's Kurtz to be Rosenthal's replacement. As savory as that irony would be -- Haberman was famously fired by Rosenthal early in the reporter's career and told, in essence, you'll never work at this paper again -- a Times spokeswoman would not confirm that he had the job. "You will find out when the readers find out," she said.

Meanwhile, watch for Abe Rosenthal's byline somewhere soon. When I ask him if he's thinking of what to do next he responds with a heartfelt, "You bet your sweet patootie I am!" There are offers, he says, people telling him he should write a book, that he owes it to history. "I don't know about history," he says, "but maybe I owe it to myself."

In the meanwhile, he's installed a fax and was trying to get his computer working when I talked to him. "Are you good on computers?" he asks me. "I thought to make this time worthwhile, aside from talking to you, I could get you to fix my computer."

I have a tech support person who does that, I tell him. "I don't know who's going to do my tech now," he sighs. "I have to learn all these new things, like how to install a fax machine and where to get stamps."

They sell them by mail now, I tell him, prompting one last bit of wisdom.

"What's the point of that?" he asks. "Every civilized person buys stamps only when they need them."

Shares