Off the coast of South Korea, the city of New Songdo, a bold new experiment in urban planning is rising on a man-made island in the Yellow Sea -- the most ambitious instant city since Brasília appeared fifty years ago. Its hundred-acre Central Park was modeled, like so much of the city, on Manhattan. Climbing on all sides is a mix of low-rises and sleek spires, condos, offices, even South Korea's tallest building, the 1,001-foot Northeast Asia Trade Tower.

Worried about being squeezed by its neighbors, New Songdo is Korea's earnest attempt to build an answer to Hong Kong. To make expatriates feel at home, its malls are modeled on Beverly Hills', and Jack Nicklaus designed the golf course. But its most salient feature is shrouded in perpetual haze opposite a twelve-mile-long bridge that is one of the world's longest. On the far side is Incheon International Airport, which opened in 2001 on another man-made island and instantly became one of the world's busiest hubs.

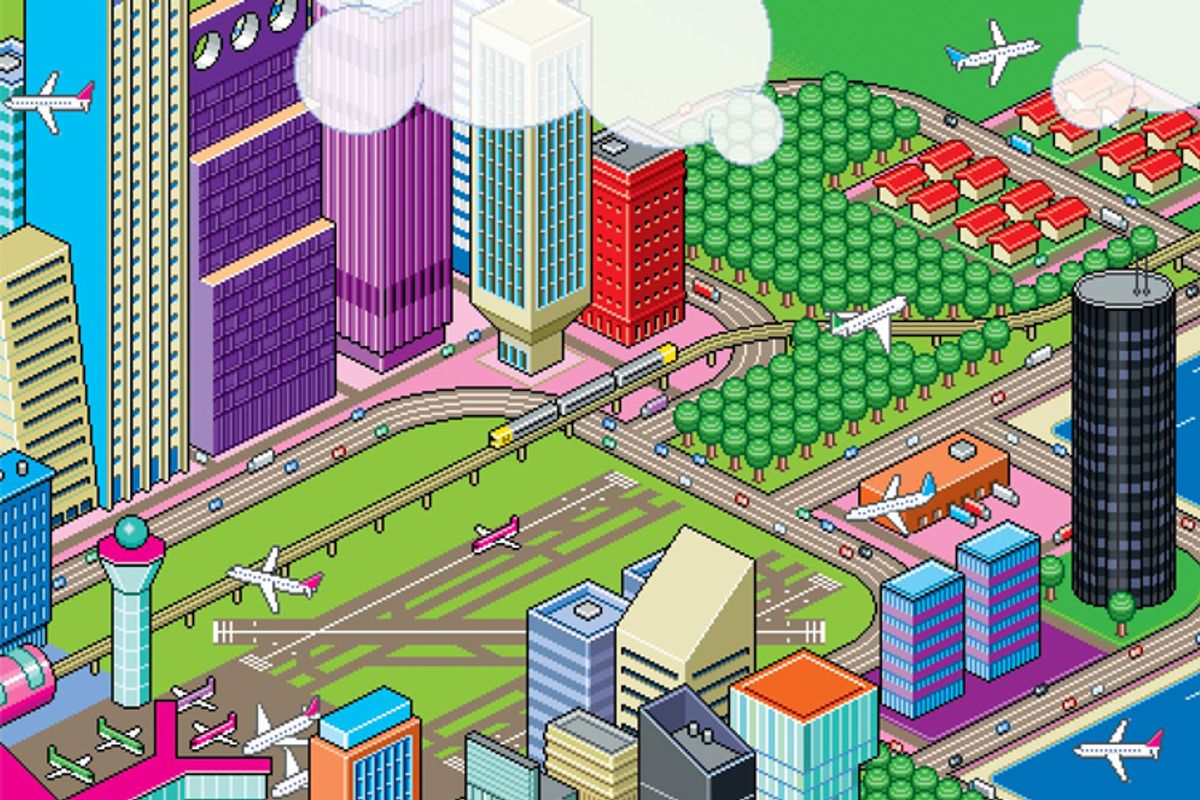

New Songdo is the most ambitious recent example of a new trend in urban construction -- the "Aerotropolis" -- that is in the process of revolutionizing the way we think of cities. It's a concept being championed by John Kasarda, a professor at the University of North Carolina. Kasarda envisions a radical (and some might say bone- chilling) vision of the future: rather than banish airports to the edge of town and then do our best to avoid them, we will build this century's cities around them. Aerotropoli designed according to his principles are under way across China, India, the Middle East, and Africa, and on the fringes of cities as desperate as Detroit and as old as Amsterdam. In Kasarda's opinion, any city can be one. And every city should be.

What does it mean to live everyday life in relation to the airport? And are we mentally prepared to do it? These are urgent questions for all of us. The age of suburbia is passing, just as the economy that drove it -- cheap cars, cheaper gas, still; cheaper mortgages, and free highways -- is passing with it. What's replaced it is the Instant Age, with its global economy of ideas -- of people, really -- and the lightweight, infinitely configurable expressions of those ideas: iPhones, solar panels, and the human capital in the Shanghai office. These are the things that can't wait, the things we pay dear prices for and need right this second -- even though they're being minted on the far side of the world.

Planes carry the products of the Instant Age -- what we want, right now, and typically our most ingenious creations. Wanting the world right this instant has created incalculable wealth, completely reconfigured how many companies and even industries operate, and is now willing entire cities into being. It's just that we tend to notice only when our choices are taken away from us.

When the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted violently in April 2010, ash carried into the upper atmosphere drifted southward, forcing a shutdown of European airspace. For more than a week, tens of thousands of flights were canceled daily. Six million travelers were trapped, and millions of others were grounded at home. Everyone seemed to have a friend on Facebook who was stuck. Thousands rediscovered trains. Professional wrestlers, opera singers, and musicians missed performances; long-distance runners missed marathons. The actor John Cleese hired a taxi to drive him from Oslo to Brussels -- the fare came to $5,000. President Obama, Gordon Brown, Nicolas Sarkozy, and Angela Merkel all missed the funeral of Polish president Lech Kaczynski, who had died the weekend before in a plane crash.

As the crisis dragged on, the scope of what we'd come to take for granted kept expanding. Even the notion of European integration turned out to be one of air travel's inventions. As the Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum noted, "Over the last two decades -- almost without anyone really noticing it -- Europeans have begun, in at least this narrow sense, to live like Americans: They move abroad for work, live for a while in one country, and then move to another, eventually going home or maybe not. They do business in countries where they don't know the language, go on vacation in the Mediterranean and in the Baltic, visit their mothers on the weekends. Skeptics who thought the European single market would never function because there would be no labor mobility in Europe have been proved wrong."

But is the opposite also true? Do we really need to rearrange our lives to better serve these slices of our self-interest? John Kasarda's answer is an emphatic yes. "I see organized competition, strategy, and structure as the major forces shaping human life, not individual actions," he professed. "I don't believe in 'agency,'" sociology-speak for free will. "Agency is inevitably trumped by structure."

Most of us are shaped by the family and community we are born into. Taken on its face, it's a reductionist worldview, but his underlying point is that our slightest whims, multiplied several billion times and duly noted by the marketplace, have already had the effect of conjuring aerotropoli where you'd least expect them, transforming everything and everyone they touch. It's no wonder, then, that developing nations such as China and India have been the aerotropolis's most eager adopters. They see it as an indispensable weapon for hijacking the world's trade routes. China's grand plans are perhaps more ambitious than anyone realizes -- it intends to keep adding factories, corner the market on green energy technologies, double down on its export-driven growth strategy, and chart a New Silk Road to markets in Africa and the Middle East.

The goal is to keep a lid on dissent by lifting another six hundred million citizens out of absolute poverty. The plan is to pack up the factory towns along the coast and move them inland. And the key is a network of a hundred new airports under construction in the hinterlands, which will connect these provincial cities to each other and to customers overseas. Twenty thousand factories have already closed, while a city eight hundred miles west of Shanghai named Chongqing has been chosen as China's answer to Chicago. Chongqing is currently growing at eight times the speed of the Windy City during the Gilded Age, adding three hundred thousand new residents a year. But it has never had a window on the world until now.

More than cheap laptops are at stake. The United Nations expects 115 million tourists a year to leave the Middle Kingdom by 2020. The most closed society in history is poised to make its presence felt outside its factories -- in our cities, on our beaches, and waiting in line at the Magic Kingdom. They're signing up for "foreclosure tours" to buy the homes we can no longer afford. The pace and scale of such urbanization threaten to overrun every model for building cities we've ever had. Architects and urban planners are in crisis about what to do with cities like Chongqing -- or just about any city in China, India, and even established but sprawling capitals like Bangkok and Seoul.

Rem Koolhaas coined the phrase "generic city" to describe megalopolises that throw tentacles in all directions, following neither form nor function. Kasarda believes the aerotropolis offers an antidote, imposing a hierarchy of needs on cities so that they openly and honestly express their true purpose: creating work for their inhabitants and competitiveness for their nations.

For Bangkok, he drafted plans to transform the swampy sprawl east of the city into an ideal aerotropolis surrounding its new airport, Suvarnabhumi. In his sketches, the outermost rings extend nearly twenty miles into the countryside from the runways. There, giant clusters of apartment towers and bungalows would take shape, the former for housing Thais working the assembly lines and cargo hubs in the inner rings, the latter for the expatriate armies imported by the various multinationals expected to set up shop around the airport. (Golf courses would keep the expats happy, as would shopping malls, movie theaters, and schools that seem airlifted straight from Southern California.)

It didn't happen. A high-speed rail link costing more than a half a billion dollars connects Suvarnabhumi to Bangkok, but the rest of Kasarda's plans were scuttled by not one, but two coups deposing supportive prime ministers, dropping his project into limbo. The riotous sprawl of Bangkok, meanwhile, keeps creeping toward the site like kudzu.

In Amsterdam, home to the world's first aerotropolis-by-design, Dutch planners have a saying:

The airport leaves the city.

The city follows the airport.

The airport becomes a city.

Although Kasarda's models are more elaborate, the fact remains: the aerotropolis is a city with a center. As such, it represents a return to the way our cities were built and how they produced some of our greatest monuments. We have not built high-rise cities in Manhattan's mold since the turn of the previous century, when the owners of the New York Central railroad oversaw the construction of a shining "Terminal City" above Grand Central's tracks buried beneath Park Avenue -- thirty square blocks of midtown Manhattan and some of the most prestigious real estate in the world. Cities since then have followed the galactic model of greater Los Angeles and its sclerotic freeways. The aerotropolis offers a new transportation paradigm powerful and compelling enough to assert itself as the bustling center of commerce within a city whose hinterlands lie a continent away. "Look for yesterday's busiest train terminals and you will find today's great urban centers. Look for today's busiest airports and you will find the great urban centers of tomorrow. This is the union of urban planning, airport planning, and business strategy," Kasarda told me. "And the whole will be something altogether different than the sum of its parts."

But what if the center cannot hold? What if globalism falls apart? There is a growing Greek chorus warning us the age of air travel is over, undone by the twin calamities of peak oil and climate change. They point to oil prices tripling over the last decade, while noting that a flight from New York to London releases more green house gases into the upper reaches of the stratosphere than the thirstiest Hummer when driven for a year. They find it impossible to reconcile our urgent wish to go green with jaunts across the country or continent -- the reason why Britain has elected to rein in airport expansion. Fortunately, their thinking goes, the imminent exhaustion of cheap oil will take care of the problem for us.

Then again, Judgment Day has been repeatedly postponed. For one thing, airliners are more virtuous and resilient than you might expect. China's airports aren't the source of its noxious air; its coal-burning power plants are. (China burns more coal than the United States, Europe, and Japan combined.) In the United States, as many as half of our own emissions emanate from "the built environment," the energy consumed to build and service sprawl. We emit more carbon living in McMansions.

For another, air travel's actual share of our carbon footprints is currently 3 percent and falling (at least in the United States), thanks to a bounty of incremental and potentially revolutionary advances meant to slow and hopefully end its carbon contributions. The next generation of airliners, headlined by Boeing's 787 Dreamliner, is lighter and more fuel efficient than last century's models, complemented by new engines that burn quietly and clean. Airlines thirsty for fuel that's both sustainably cheap and green are looking to high-octane biofuels refined from algae. Virgin Atlantic's grandstanding chairman Sir Richard Branson has pledged all of his airline's profits through 2016 (an estimated $3 billion) on R & D toward this end. Green crude might reliably cost $80 a barrel, enough to save the industry as we know it, and not a moment too soon.

Despite a decade's worth of high oil prices, terrorism fears, and the airlines' endless nickel- and-diming, we have never flown as far or in greater numbers than we do right now. As recently as 1999 (when gas still cost a dollar a gallon), JetBlue had yet to start flying, Ryanair had no website, and starting your own airline was illegal in both China and India. No one west of Jerusalem had even heard of Dubai, and it was impossible to take a non-stop flight from New York to New Delhi or Beijing. The world may or may not have flattened since then, but there's a lot less changing planes. In the end, we won't stop flying for the simple reason that quitting now would run counter to our human impulse to roam. Will you be the one to tell a hundred million Chinese tourists (and another hundred million Indians) they'll have to stay home?

Excerpted from "Aerotropolis: The Way We'll Live Next" by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay, published in March 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2011 by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay. All rights reserved.

John D. Kasarda is a professor at the University of North Carolina's Fenan-Flagler Business School. Greg Lindsay has written for Time, Fortune, BusinessWeek and Fast Company.

Shares