Of course Tim suggested we meet at the bar. Where else would we meet? It's where the guys go every day after work, 5 to 7 p.m. Tim likes to brag that they get the employee discount.

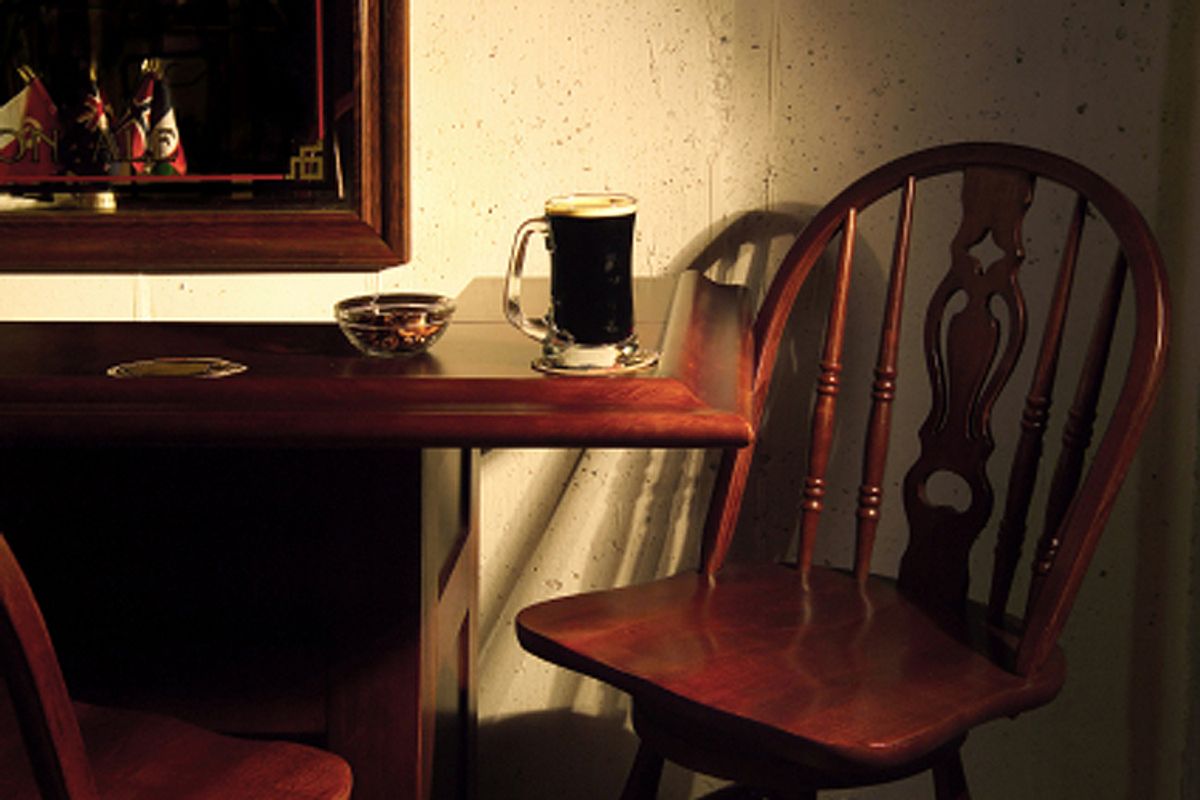

I used to love to join them there. Whenever I'd come home to visit, I'd find the guys in that back booth, steady as a sundial. I'd order a Stella, or a Harp, something tart enough to sting but light enough to drink by the gallon. I'd drain it while they told their stories, and we shook off the frustration of the day, and became an easier, funnier version of ourselves. And every 15 minutes, a woman in a tank top and a casual ponytail would appear. "Can I get you another?" she'd ask, pointing to the empty glass.

It was the world's easiest question. The only question that might have been easier was, "Where should we meet?" because the answer was always: the bar.

And so I knew I was making everything more difficult, I knew I was disrupting the natural flow of the universe when I emailed Tim and said, "Actually, I quit drinking -- do you mind if we meet for lunch or coffee?"

It was such a simple request. Why did it feel like I was asking everyone to stop breathing for a while?

I quit drinking more than a year ago. It was time. None of my closest friends said, "Wow, I didn't know you had a problem," because that was untrue. What they mostly said was, "Good for you." And, "Let me know how I can be helpful." But what I struggled with -- and still struggle with, more than 365 days after I drained my last glass of sauvignon blanc at a friend's wedding reception -- was telling people who weren't my closest friends. Who might have been close, but not that close.

I have come to dread the moment when I need to tell an acquaintance that I have quit drinking.

I do it too fast: "How are you?" / "Oh, I quit drinking."

I do it way too slowly, drag it out, so that what might have seemed like a casual lifestyle switch now seems grim and problematic: "I'm OK. I quit drinking. Had a bit of a problem. Bit dark there for a while. Beware of Mexican busboys, that's all I'm going to say."

More often, I don't say anything at all. Avoid the topic entirely. I understand that most people, honestly, don't give a damn.

But since moving back to Texas from New York last month -- and embarking on the string of reunion dinners and meet-ups this entails -- I feel I owe my former drinking buddies fair warning. I know what it was like to anticipate a debauched evening at the bar only to hear, "I'm pregnant!" Or, "I've decided to cut back." And what was going to be a last-call rager got tragically downshifted to two guilty glasses and bed by 11 p.m. Yay, good for you, I'd say, sipping a glass of wine that suddenly felt like it was the size of a thimble.

But the bar is just where people meet here. "Want to meet for a drink?" they ask, and it narrows all of life's confusing dilemmas -- uptown or downtown? Healthy or decadent? Outside or inside? -- down to one convenient locale. For five years, whenever I visited, we met at the bar (to be perfectly accurate, three different bars, as each cluster of friends had their own go-to place) and to walk in was like returning to a family reunion, if your extended family was warm and hilarious and generously happy to see you. I would drink all night and have, like, a $5 bar tab.

"See what you're missing in New York?" my most trusted drinking buddy would ask. And I did.

For decades I defined myself as a drinker, spent weekends and evenings in the cozy confines of a nice, steady stupor, but now I confronted a problem bigger than the mere practical issue of where to meet. Indeed, it was the central crisis of my life: I did not know what to do with myself. For a year, I had buried myself in work. On Saturdays, if I felt itchy, I took long walks along the Hudson River -- six-, seven-hour walks, listening to podcasts compulsively. Having shifted around my job to create more free time and transferred myself back to a city that moved at roughly the pace of a slow waltz, I felt an anxious emptiness without my laptop in front of me. I did yoga. I read books. I went to meetings that served bad coffee. But real, live human interaction -- I missed it. This is a high-class luxury problem, I know, but still, it plagued me as if I were an angsty college sophomore: Who am I, and what do I like to do?

When Tim and I did meet for lunch, at a place I remembered for its hearty salads, we talked about this for a bit. I was expressing disappointment that I hadn't seen the guys from the magazine he runs, the guys I usually catch up with over a pint or four.

"We could go bowling," Tim says. "Or play kickball."

Ugh: sports. I didn't want to sound too negative. But how do you explain to someone you only know through bar chatter that you are embarrassed by the world? That you can't do anything that involves running, sweating or standing outside? This is why drinking was so convenient. It was a smoke screen for the fact that I sucked at everything else.

"You could have a game night over at your house," he says. "Or start a book group."

"Oooh," I say. "Would you go to a book group if I had one?"

He avoids this question, which I take as an honest no. Everything Tim comes up with -- a Rangers game, a movie night outside, a music festival -- I respond to with a strained nod. The truth is I always felt an allergy to these perky organized activities; to the tyranny of hobbies. Even when I covered live music for the paper, I was the one in the back, slunk in my seat and talking to the bartender.

"Couldn't you just go to the bar and not drink?" Tim asks.

This is a fair question. It is a question that, for most of my life, I would answer yes to, because yes seemed like the only reasonable response.

In fact, about a year and a half ago -- when I was trying to quit, and slipping -- that is exactly what I said when Tim asked me to meet him at the bar. I was in town, and we had some business to discuss, and while I had stumbled putting together two weeks, it only made sense to convene in that familiar back booth. To keep myself honest, I drove my parents' Prius to the bar. A kind of moral insurance.

"You're not drinking tonight?" Tim asked when I ordered my second tonic water. From where I sat, I could smell the hops from his Stella. It made my mouth water.

"I've been having trouble sleeping," I told him, to avoid the Big Confession. This was true. Ever since college, I would startle awake four hours after I passed out, and the rest of the day would be one failed attempt to coax myself back to slumber. I would spend hours simply enumerating my failures: I forgot to email that woman! I forgot to pay that credit card bill! I forgot to get married and have kids!

"I hear you," Tim said. "Drinking gets harder when you get older."

I nodded. "I'll drink later tonight," I said, which was a lie when I said it, but sounded like a brilliant plan as soon as it fell off my tongue. "I just don't want to get too drunk."

Fifteen minutes later, when the pretty woman with the casual ponytail walked past our table, I ordered a Stella. And when Tim left 30 minutes later to have dinner with his wife and kids, I stayed and ordered another. I met my most trusted drinking buddy at a second bar, then accompanied him to a third. The night was a blur of good times. At 3 a.m., I got behind the wheel of the car (which was an insanely stupid thing to do, by the way). I was pulled over by a cop driving home without my lights on.

"I have been drinking, officer," I said, my voice shaking. "But also, this is my parents' car. And have you ever tried to drive a Prius? It's really confusing."

I charmed my way out of that DUI. But so much for quitting. I'd probably had 10 drinks that night.

So the short answer to Tim's reasonable question was no. Sadly, stupidly: No. No, I couldn't meet them at the bar and not drink. And even if I could, I didn't particularly want to be reminded of that extravagant failure, or the hundreds of others that trailed behind me. A year after I'd stopped waking up in the middle of the night, consumed with remorse, I wanted new failures. I was tired of the same old regret.

As I spear the lettuce on my chicken Caesar, I try to explain this, somewhat, to Tim. "Back when I used to join you guys at the bar, you all left at 7 p.m. But I never left. I would stay out till midnight. I would stay out till 2 a.m."

"I can solve that problem," Tim said. "Get married, and have kids."

He's right, in a way. I have friends who are a testament to this radical moderation management program, who drank lustily in their 20s but have now happily settled down into responsible, two-drink-maximum adulthood. If you look at drinking patterns over a lifetime, this is where the cliff happens. When people start a family, their drinking just plummets.

"But I don't have a husband," I said. "And I don't have kids." This isn't a sore subject yet, but at 36 years old, it's approaching one. And it doesn't take a genius to add up all the time I spent in bars and all the bruises I got from falling down the steps, and the lack of commitment I had to anything beyond my cat and my laptop and a cold pint of Pilsner Urquell, and determine that were I to want a husband and kids, the bar was perhaps not the keenest place to find them.

But this is just my experience. It's not Tim's experience. Tim leaves the bar at 7 p.m. every night, steady as a sundial, and goes home to his kids and his wife -- who are, in case you were wondering, all quite beautiful. So he gets to keep the bar, while I can't touch the bar without fearing that my life might implode, and part of me feels unspeakably blue that this is how it turned out.

"You could start crochet bombing." I'm driving Tim back to his office now, and he is riffing. I think he just likes to hear himself talk. "You could start an activity club. You could join a church."

"I think I might become someone crafty," I say, being serious, though he is not. I always admired women who sewed their own clothes and had unusual hair styles and tried to find art in the incidental details of their life: A throw rug, a couch pillow. Lately, I have been shopping at vintage stores, which I always thought were reserved for cool girls with funky glasses, but it occurred to me that all I was missing, really, was the funky glasses. "I know the DIY trend hit about five years ago," I tell Tim. "But I like coming to trends after they've passed. There's less competition."

What I really like to do, though -- what I like more than anything else, more than anything in the world, whether I'm at the bar or languishing in my apartment -- is to talk to people. I like to have honest conversations with other humans that surprise me, and challenge me, and make me think about my life in new ways. It's what I always wanted from the bar in the first place. And it strikes me, driving home that day, that it's exactly what I just had.

Shares