To reach The Village at Hiddenbrooke, A Thomas Kinkade Painter of Light™ Community, you must first cross the San Francisco Bay Bridge and drive 30 minutes northeast of the city. You pass the cozy liberal bastion of Berkeley, the smoke-belching oil refineries of Richmond, and cross the girdered Carquinas Bridge before entering the tract-housing grid of suburban Vallejo. Just beyond the Marine World Africa USA theme park -- next to a Smorga Bob's restaurant and a Rite Aid -- there is a freeway signboard with the slogan "Get Away, Every Day. The Village at Hiddenbrooke," which features photographs of green grass, placid golfers and the steak dinners they presumably eat for dinner.

The Village at Hiddenbrooke lies just over the hill from Vallejo, where the city peters out into cow-dotted farmland. Hiddenbrooke is a 2-year-old development of 10 planned communities clustered together on 1,300 acres, with a golf course at the center. Thomas Kinkade's village is its most recent, and most high-profile, addition. Its opening in September drew a crowd of more than 2,000.

The village is, according to its marketing material, a "vision of simpler times," a "neighborhood of extraordinary design and detail" with "cottage-style homes that are filled with warmth and personality" and "garden-style landscaping with meandering pathways, benches, water features and secret places." The covers of the promotional pamphlets feature a Thomas Kinkade painting of a charming, rain-dappled village -- complete with church steeple, families out walking the pet Dalmatian and thickets of flowers.

All of this -- the golfing and steak dinners, the rain-dappled Dalmatian doggies and the happy-go-lucky hollyhocks -- sounds so absolutely charming and idyllic that it isn't surprising that the village doesn't quite live up to its billing. What is surprising, though, is just how far short of the mark it falls. I arrived at Kinkade's Village expecting to be appalled by a horror show of treacly Cotswold kitsch; I was even more horrified by its absence.

To understand the Village, you must first understand who Thomas Kinkade is. Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light™, bills himself as "the nation's most collected living artist." His paintings are typically luminous landscapes of romantic rustic villages, serene rivers, cozy churches, darling stone cottages and flower-strewn cobblestone streets -- or, as he categorizes them on his Web site, "Bridges," "Gazebos," "Seascapes," "Holidays," "Gates," "Inspirational," "Lighthouses" and "Memories."

For every setting, Kinkade chooses a dramatic lighting scenario: neon purple sunsets, glowing cottage windows, tumescent clouds, bright springtime sunshine. His work is sentimental, patriotic, quaint and spiritual, offering the kind of images you might find in turn-of-the-century children's storybooks. Many of his works refer directly to God, prayer and the Scriptures. (Paintings might be titled "The Hour of Prayer" or include a brass plate engraved with a Psalm).

Thomas Kinkade has sold some 10 million works -- "paintings" isn't exactly the right term, since most of the items are merely prints that have been "highlighted" with a few daubs of paint by the "master highlighters" who sit in Kinkade's 350 galleries and do their magic right in front of the customers. These works, much like Beanie Babies, are sold in limited editions, which spurs Kinkade's fans to pay outrageous prices -- thousands of dollars, typically -- for them. (Regardless, his company, Media Arts, is currently in serious financial straits, and has posted losses for four straight quarters).

Kinkade has parlayed his fame into an entire country-cottage industry of Kinkade-licensed products, as seen on QVC -- home furnishings, La-Z-Boy chairs and sofas, wallpaper, linens, china, stationery sets, Hallmark greeting cards and so on. Kinkade has also recently co-authored a novel. The Village at Hiddenbrooke bills itself as the culmination of Kinkade's vision: an actual manifestation of the quaint cottages, charming gazebos and inspiring landscapes in his artwork.

Except that it isn't. What you find in the rolling hills behind Vallejo is the exact opposite of the Kinkadeian ideal. Instead of quaint cottages, there's generic tract housing; instead of lush landscapes, concrete patios; instead of a cozy village, there's a bland collection of homes with nothing -- not a church, not a cafe, not even a town square -- to draw them together.

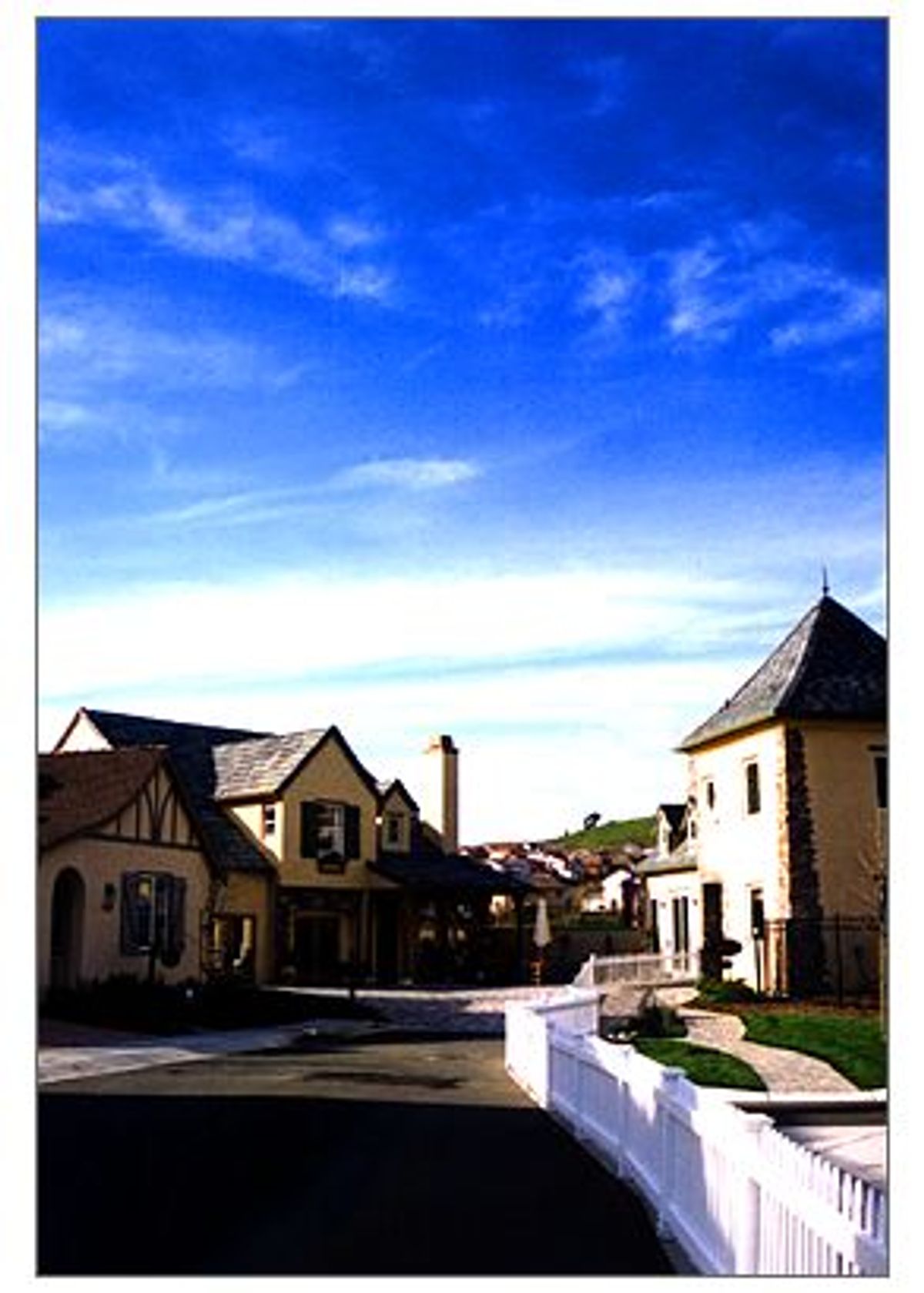

Your first glimpse of Hiddenbrooke features four enormous satellite dishes and a radio tower, nestled in a green valley next to an oblivious troop of grazing cows from the adjacent farm. The second thing you see upon arrival in Hiddenbrooke is an endless stretch of the community's semi-identical greige tract homes, squeezed in close. "The Village" is a cluster of 101 homes behind a small stone gate, wedged between the similarly gated communities of St. Andrews, The Heights and The Masters. From a distance, these communities look mostly the same.

Only 31 of the Village homes have been built so far (with 30 sold, and seven actually occupied), and the area is still busy with tractors and bulldozers. But four model homes are open to entice the public: the Everett, the Winsor, the Chandler, and the Merritt, each named after one of Kinkade's children. Although each features a vague architectural "style" (i.e. Tudor, Victorian, etc.), none of the homes bear much resemblance to the stone-and-thatch-roof cottages of Kinkade's paintings; rather, they bear a striking resemblance to houses in the planned communities up the road, with the same cookie-cutter, Superglued feel. Perhaps this is because Kinkade did not actually design the homes himself -- instead, he licensed his name and artistic sensibilities to a development firm called Taylor Woodrow, which designed the homes but submitted all plans to Kinkade for approval. (Kinkade has declined to comment on Hiddenbrooke, and referred calls about the homes to the developer.)

There are, for example, none of the flowering bushes or graceful trees that are characteristic of Kinkade's paintings -- according to the planners, abundant landscaping is just too expensive to maintain. None of the homes in the village have gardens at all, though they do have tiny patios. In fact, the entire village is devoid of any foliage, save for a few tired-looking pansies planted in front of the model homes (planners promise a small amount of similar landscaping for each home). And although those lucky enough to live adjacent to the golf course can gaze out their windows upon Hiddenbrooke's grassy hills and miniature lake, there isn't a tree visible for miles, let alone a hollyhock or a daffodil, and there are no plans to plant any significant number of them.

The Hiddenbrooke resident must also forgo another mainstay of Kinkade's works -- the woodsy winter fireplace smoke oozing from the chimney. Fireplaces here are gas only. There's no quaint neighborhood church in the village, either; nor is there a grocery store, a community square, or a restaurant -- heck, there isn't even a corner store. If you want to shop or pray or eat, you'll need to get on the freeway and head into Vallejo, since Hiddenbrooke is a residential-only zone.

As for the houses themselves, while they are perfectly serviceable and attractive enough, they aren't particularly charming or quaint. The only Kinkade-like architectural details in the village are the stone entry gates and turret (which houses a Thomas Kinkade gallery), and the decorating in the model homes -- decorating which, of course, will not be included in the home one might purchase. These walk-in dioramas of Kinkade merchandise exude a certain Kinkadeian atmosphere -- a multiculti, artsy-fartsy, touchy-feely kind of family vibe. The libraries of the model homes included such volumes as "Soup: A Way of Life"; biographies of Maria Callas and the Dalai Lama; assorted coffee table books featuring impressionist painters (no modern art here, mister!); self-help books like "Real Life, Real Answers" and "The Retreat to Commitment"; Danielle Steel and John Grisham novels; and, probably since Northern California has a large Hispanic population, a tome called "Mexican-Americans: The Ambivalent Minority." (The Bible is conspicuously absent, which is noteworthy considering Kinkade's religious fervor; apparently, the developers didn't want to scare off any potential Hindus or Zoroastrians.)

Fake family photos of happy, wholesome, all-American families frolicking at beaches, golf courses and weddings adorn the walls. Floral and chintz fabrics abound, and the "children's rooms" are done up in golf themes and horse themes and, for one poor mythical college student, an entire University of California at Davis theme (including UC-Davis wallpaper, pillows, pennants, and framed campus photographs.) And while the homes all boast computers -- this is high-tech country, after all -- the fictional "matriarch" of one model home still pens her thank-you notes the old-fashioned way: in ink, on Thomas Kinkade stationery. ("Fran -- Our new home is beautiful! We love the small town feel and the community is wonderful. It is a joy to live in our new home.")

And, of course, enormous Kinkade prints hang on every wall -- one model home boasted no less than 14 Kinkade originals. This is some consolation: even if the village homes don't actually have views or thatched roofs or mossy masonry or gardens bursting with flowers or sparkling waterfalls descending down purple cliffs, you can look at those things on your walls.

It may be unfair to expect a $400,000-per-home planned community to meticulously replicate the Kinkade vision, what with all that stonework and lush landscaping. And despite the heavy "building the vision of Kinkade!" emphasis in marketing material, the public relations team is certainly aware that "vision," in this case, is a loose term. To the press, Hiddenbrooke flacks describe the community as being merely "inspired" by Kinkade. Says Fran Leach, marketing director for Taylor Woodrow: "We couldn't build a Thomas Kinkade home because it'd be priced prohibitively; when we had to pick and choose [Kinkade-like details] we chose gabled roofs, dormers, white picket fences. We really tried to incorporate a 1920s look; an older feel, a slower time, those types of things."

Perhaps the greatest losses in the translation of the Kinkade fantasy to real life are the church with its familiar steeple, and the ever-present village square. No matter what you might think of Kinkade's artistic merits, his celebrity suggests that he's tapped into a collective longing among Americans for real community. Some would argue that Kinkade's idealized vision of America is a Frank Capra/ Norman Rockwell fantasy. But no matter how gauzy Kinkade's vision, there is no question that the current suburban aesthetic makes us want it -- bad.

For decades, planners and sociologists, following Jane Jacobs' 1961 classic "The Death and Life of Great American Cities," have been decrying the devastation wrought by the loss of vital urban living centers to suburban sprawl. "The suburban build-out of the last 50 years has been a fiasco for our culture, because it destroyed our most important civic communities -- it impoverished the public realm, and in so doing, it impoverished our public life," says James Howard Kunstler, author of "The City in Mind."

"The idea of 'country life' as embodied in suburbia becomes more and more of a cartoon," he says. "That's part of the great unexpressed agony of our time -- that almost nowhere does suburbia deliver what it promised. You're living on top of people and stuck in traffic all the time, but there is no cultural or civic amenity that goes with it."

In the 55 years since Levittown, America's first standardized community, was built, countless planned communities, housing subdivisions and tract homes have sprouted, creating new visions -- bigger, cheaper, fancier, cheesier -- of the American dream. Sprawling infinitely, the communities banish the old concept of neighborhood with zoning that allows homes, the occasional country club and nothing more. With names like "Tranquility," "Inspiration" and "Aura," the newest tracts attempt to make the best of increasingly cramped locations on disappearing open space far from town by touting peace and privacy.

In the last two decades, the new urbanist movement has spawned an alternative, the planned town -- designed to reduce suburban sprawl and create community centers. These experiments, such as the Florida settlements of Celebration (the infamous Disney village) and Seaside (as seen in "The Truman Show"), consist of clustered neighborhoods in which central shopping areas are within walking distance and cars are unnecessary. The planned town is, in its way, perfectly Kinkadeian: A community of distinct architectural design in which residents might actually walk a picturesque Dalmatian to the little grocery store to pick up some fertilizer for a colorful garden.

The planned town has been a slow starter -- only a few hundred communities have applied its principles -- largely due to laws that discourage the mixed-use zoning of new-urbanist developments. Meanwhile, plans for conventional developments tend to sail through planning commissions eager to increase tax revenues, despite some distant, but growing, grumbling about sprawl.

"Thomas Kinkade and new urbanism are parallel universes," says Kunstler dismissively. "This development in Vallejo is an exercise in conventional suburban development with a sentimental marketing gimmick. Kinkade represents the gift shop solution to the problem; the new urbanists are serious people. "

Yet the Village at Hiddenbrooke is, in a way, a lesson in lost opportunities. Imagine if the enormously famous Kinkade had brought his "artistic sensibilities" to a new-urbanist architect and an enlightened group of town planners instead of an enormous profit-seeking development conglomerate, and matched his cutesy aesthetics with their concepts of a new American suburb: He could have built something responsible and meaningful, and helped promote a community-building movement that is still struggling for widespread recognition.

Even if you loathe Cotswold kitsch, there's something to be said for building tree-filled towns with hidden gazebos and public meeting places. But the vision needs to go deeper that the paint on a Thomas Kinkade "original."

Shares