The wittiest, most entertaining story about gender in recent memory has just reached its conclusion. This month, writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Pia Guerra released "Whys and Wherefores," the 10th and final volume collecting their surprise-hit comic book series "Y: The Last Man." On its surface, "Y" is a science-fiction epic and a coming-of-age story, with a touch of romance thrown in; read it a little more deeply, though, and it becomes a dead-on satire about the screwed-up gender issues of the world we know.

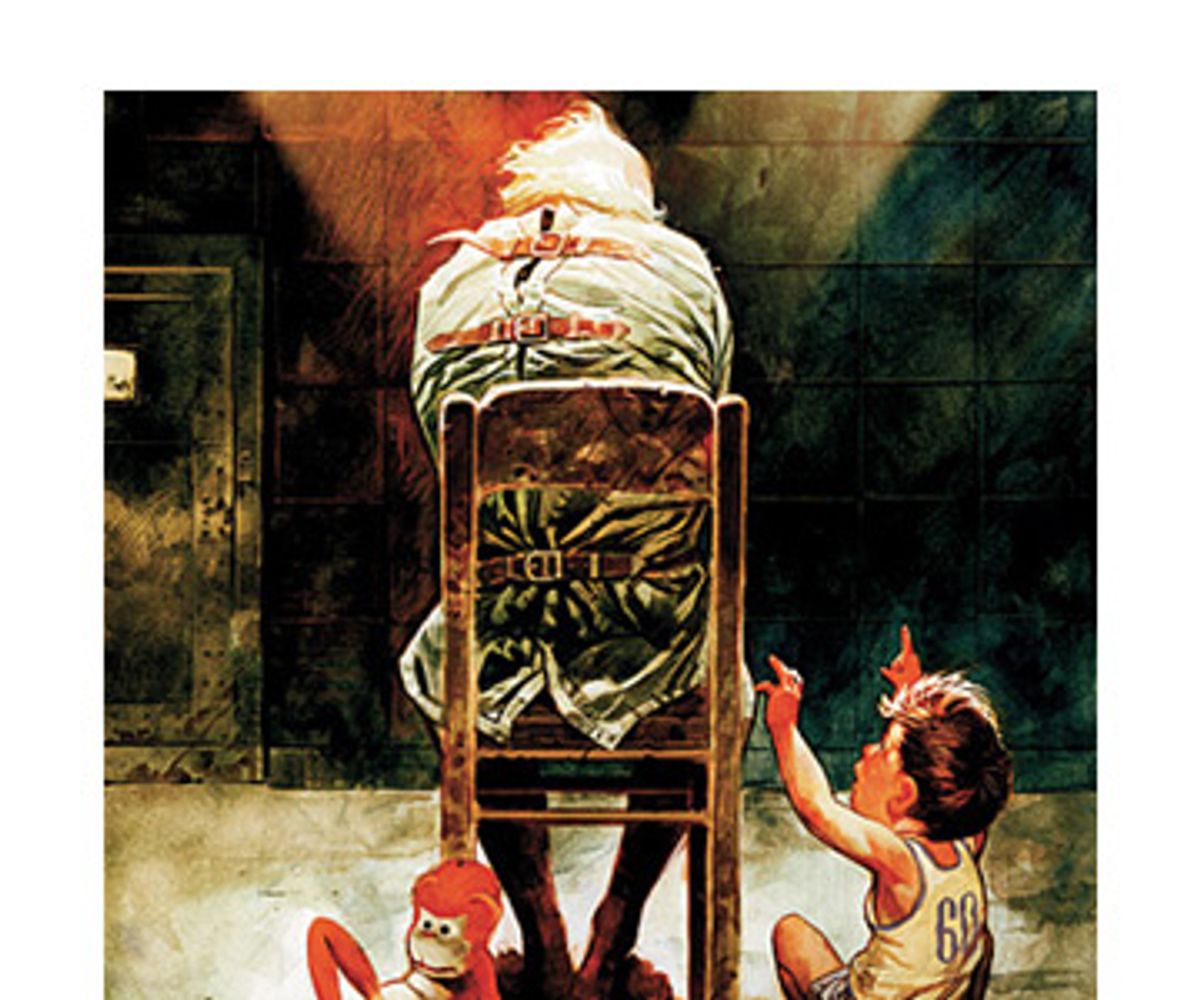

As "Unmanned," the first volume of "Y," begins, almost every man, boy and other male mammal on the planet has abruptly dropped dead in a single instant. Only two beings with Y chromosomes have been spared, for reasons unknown: Yorick Brown, a 22-year-old amateur escape artist, and his pet Capuchin monkey, Ampersand. At the moment of the disaster, Yorick is in Brooklyn, talking on the phone to his girlfriend Beth in the Australian outback, and they're cut off just as he proposes marriage to her; the rest of the series is Yorick's adventures as he travels the post-catastrophe world for the next five years, trying to find her again.

But he's got a major obstacle in his path, and it isn't just that every government on the planet wants to get its hands on the last man alive, or that roving bands of homicidal "Amazons" want to see the last vestige of male oppression scrubbed from the planet. It's that he's kind of a twit. Yorick isn't much of a hero by any standard (and neither is his sister, who actually is named Hero -- their parents really liked Shakespeare). He's a callow, bumbling dope with a reasonably good heart, but he's basically just an overgrown boy, and the overall arc of "Y" is effectively about how he becomes a man in a world of nothing but women.

The keys to Yorick's five-year journey, naturally, are the women he's surrounded by, especially the series' most indelible supporting character: his bodyguard, Agent 355. Known only by her number, she's a dreadlocked young woman who's also a totally badass assassin in the service of the Culper Ring -- a spy organization founded by George Washington (in the real world) that's taken orders from the president of the United States ever since (in "Y"). Of course, after the men are gone, you have to go a ways down the line of succession to find an acting president ... to the secretary of agriculture, it turns out.

Vaughan gets a lot of mileage out of speculating about what would happen if all men really did vanish from the Earth: Vatican City, for instance, would become a mausoleum, and so would the floor of the Tokyo stock exchange, but the Israeli military would be just fine. Long-distance commerce would be a disaster for years, thanks to the highways being blocked by enormous pileups caused by half of all drivers abruptly keeling over. Australia, as one of the few countries that allowed women to serve on submarines, would rule the waves. Supermodels would be forced into new lines of work, like driving a garbage truck full of men's corpses. (America's next top undertaker!)

But "Y" isn't an argument about what really would happen if the men were all transported far beyond the Northern Sea, or even a bildungsroman, as much as it is a wickedly clever satire of patriarchal culture. It's a story about men and the chaos and ruination they've brought to the world, in which all the "male" roles are played by female characters. There are ferociously funny little riffs on women getting by on their looks, "man-to-man" conversations, "women and children first," men as protectors and women as protected, women as sexual temptresses of men, men asking women to smile, "proving one's manhood," and practically every other kind of awful gender essentialism.

A friend of mine once complained to me that women wouldn't really act the way Vaughan's characters do -- that "Y" simply "puts a wig on" the familiar world. That's actually exactly why "Y" works, in the same way that Gilbert and Sullivan's "The Mikado" makes its satirical points about the British upper class by pretending not to be about British characters. Vaughan and Guerra's murderous female supremacist Victoria, for instance, is totally unconvincing as a woman character -- because she's a perfectly convincing male supremacist in drag. The wig is a distancing device, a way to look with fresh eyes at the assumptions about gender that normally go unspoken and the stereotypes that are common currency, and make points about how strange they are and what perpetuates them. It also makes for a much more interesting story than a serious consideration of how the world might be fundamentally different after a "gendercide."

And, in fact, virtually every character Yorick encounters in the course of "Y" is a woman doing some sort of stereotypically male thing: The series is populated by women soldiers, convicts, politicians, pirates, paparazzi. After the plague, male impersonators who can pass for the real thing are a hot commodity, and a brothel makes a mint with a robot gentleman who says things like, "Please, tell me about your day." For a while, Yorick conceals his gender identity in a time-honored way: wearing a burqa. By the end of the series, Vaughan has thoroughly demolished the heteronormative romantic-comedy scenario -- the idea that all Yorick has to do is make his way through the obstacle course separating him from Beth, and they'll live happily ever after -- as a young man's immature dream.

A lot of Vaughan's satirical moves can seem a little obvious, but that's because there's always somebody who's going to miss the joke. (Just to hammer the point home, the scientist who may have brought on the plague by attempting to give birth to her own clone is named Dr. Mann.) Vaughan and Guerra even poke fun at their own efforts: Near the end of the series, a pair of dramatists who've found that making movies forces them to dumb down their vision switch to producing comic books. "This format has all the advantages of film and none of the drawbacks," one of them declares. "It's the cheapest way to get our unfiltered vision into as many hands as possible!" (Yorick's opinion of their brainchild, "I Am Woman," about the last surviving woman in a world full of men: "Meh.")

Vaughan's been flirting with Hollywood himself lately -- he's currently one of the staff writers for TV's "Lost," and there's a "Y" movie in development -- but he's also still immersed in comics, writing his political superhero series "Ex Machina" (with artist Tony Harris) and recently contributing a story line to the "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" comics series. And for all the comparisons "Y" has gotten to HBO-style closed-ended series, it's very much a comic book: Vaughan structures it in ways that play to the strengths of the drawn page. Almost every panel ends with a little tug toward the next (a question, an off-panel voice, an unexpected event), every page ends with some kind of suspenseful moment or dramatic flourish that demands a page-turn, and every issue (or, if you prefer, chapter) ends with a very big cliffhanger.

It flows like a waterfall, and one of the things that makes the series zip along is its no-nonsense artwork. Guerra is one of the least flashy artists working in American comics: Her character, panel and page designs put clarity first and everything else second. The trade-off is that they're often a little stiff, but that's fine in the context of this story, especially because she's also terrific at getting across subtleties of facial expressions in a few simple lines. "Y" is a very conversation-heavy series, for all its bursts of action, and Guerra's straightforward staging and clean, spare compositions pretty much clear space for the character portraits that carry as much of the story as Vaughan's snappy, salty dialogue.

Guerra, for whatever reason, couldn't draw "Y" fast enough to produce an issue every month of its five-year run, so there are frequent "interlude" chapters, pencilled in a close approximation of her style by Goran Sudzuka and Paul Chadwick. (Inker José Marzán Jr., who worked on every issue of the series, unifies the look of the artwork.) The interlude chapters flesh out the back stories of various members of the cast -- there's even one devoted to Ampersand the monkey -- although they defer the progress of the main plot, sometimes maddeningly.

Considered as a whole, "Y" meanders a bit in the middle: An extended sequence involving a trip to Japan and a drug-addled Canadian pop star falls flat, and there's an ambitious failure of a sequence called "Safeword," in which Yorick manages to shed his suicidal impulses thanks to an encounter with a kindly dominatrix. There are a handful of forced coincidences wheeled into place to get the story moving, too. Still, almost every incident and object in the series ends up having some kind of symbolic resonance by the final volume.

"Whys and Wherefores" leaves open a few big questions -- there's a question implicit in the series' title, after all -- but it resolves the overall story's progression: Yorick's journey from boyhood to manhood, and the world's evolution from the wreckage of a patriarchal dystopia to something better. Most of the action of the first volume of "Y" happens near the Washington Monument; by the final volume, the scene has shifted to the rather more female Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

In an epilogue, set 60 years later, Vaughan and Guerra finally show us the sort of feminist utopia the rest of the series has carefully avoided. (A young woman, seeing a man for the first time, addresses him as "sire," then corrects herself: "No, wait. 'Sir.' Sir, right? I've never actually used that word before.") To the extent that Yorick himself is triumphant at the end of the story, he achieves his victory by refusing to do the "manly" thing. That may be the ultimate argument "Y" makes: Before the world can change for real, the stories we tell ourselves about the nature of men and women have to change, too.

Shares