The first time Alice B. Toklas met Gertrude Stein, Alice believed Gertrude to be speaking from her brooch: "She wore a large, round coral brooch, and when she talked, very little, or laughed, a good deal, I thought her voice came from her brooch. It was unlike any other else's voice -- a deep, full velvety contralto's, like two voices."

Alice also heard bells, which she believed to be an indication that she was in the presence of genius. As Gertrude writes in the "Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas," a novel about Alice's life with Gertrude in the voice of Alice (more about that later): "I may say that only three times in my life have I met a genius and each time a bell within me rang and I was not mistaken." (The other two bells rang for Alfred North Whitehead, the philosopher; and Pablo Picasso, a decent dinner companion.)

The year of their meeting was 1906. Alice was a San Francisco expatriate who came to Paris after becoming bored with serving as housewife to her brothers and father; Gertrude was an Oakland expatriate and the queen mother of a literary salon located at 27 rue de Fleurus. Gertrude had been quite fond of declaring herself a genius long before Alice heard bells, and that became the first thing they agreed upon. They also agreed that a life worth living should include plenty of food, the company of artists and writers, and a general refusal to do the things that did not please them -- like learning to drive in reverse, or continuing to entertain writers and artists who had become quarrelsome or boring.

For the 39 years that followed their first meeting, that is the life they lived. Gertrude proposed to Alice on a trip to Tuscany; afterwards they moved back to 27 rue de Fleurus, ousted Gertrude's brother, Leo (he left, writing, "I hope we will all live happily ever after and suck our respective oranges"), and set about making their home.

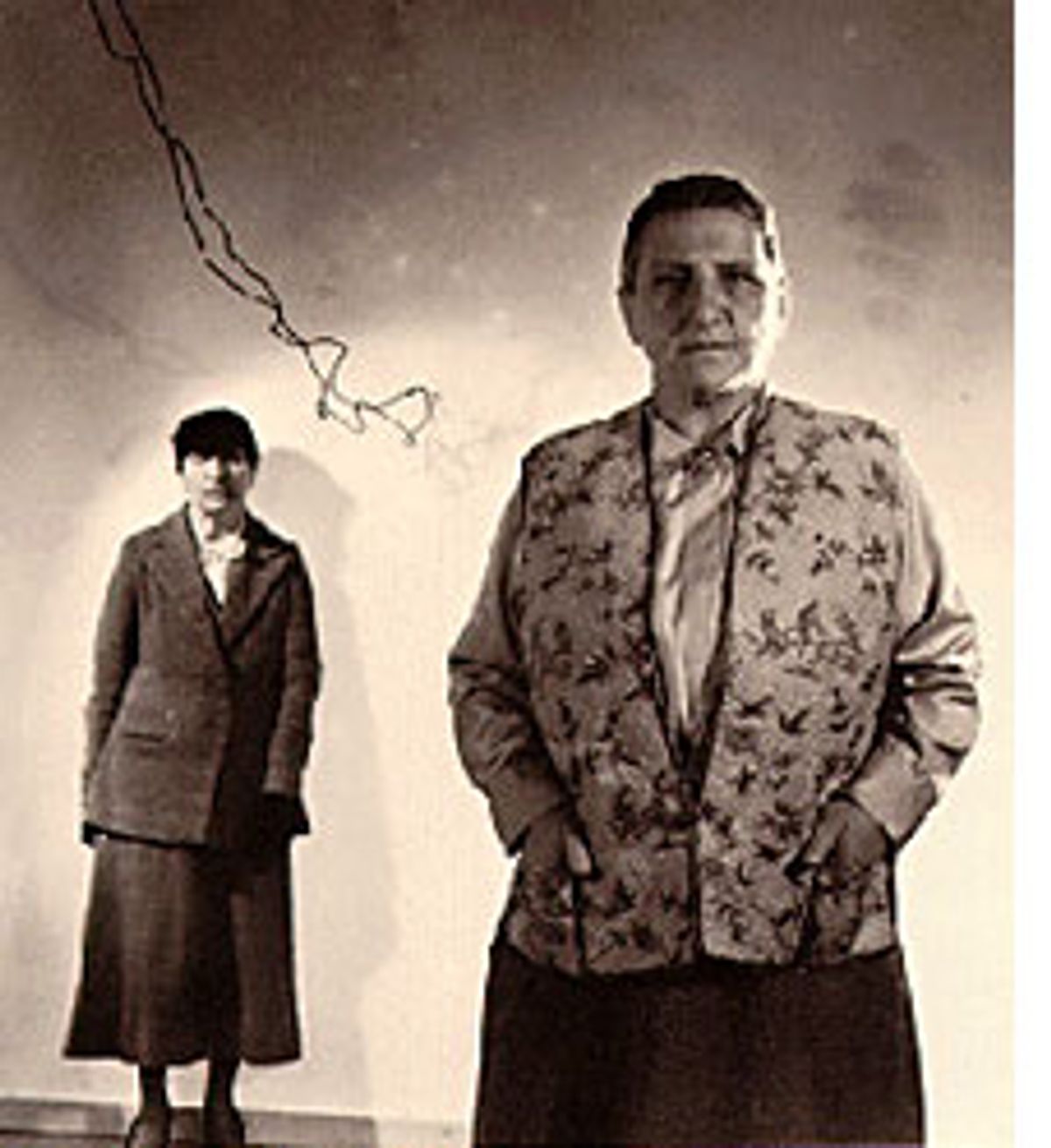

Gertrude was ample, and had, by all accounts, a large, well-shaped head which she eventually displayed with a fetching Caesar cut. Alice was small and thin with large dark eyes and a small bit of fur on her upper lip. She had a propensity for flowing dresses and gypsy earrings. When they went to visit Gertrude's brother, Julien Stein, his 3-year-old son said that he liked the man, but why did the lady have a mustache?

They lived as husband and wife, "she with a sheet of linen and he with a sheet of paper," as Gertrude is quoted in Diana Souhami's biography, "Gertrude and Alice." Gertrude, who was the genius, stayed up all night writing her strange, lovely prose, while Alice, the mistress of the house, woke early to supervise the servants, collected recipes and typed Gertrude's manuscripts.

The terms of their endearment reflect their respective roles. According to Souhami, "Alice was gay, kitten, pussy, baby, queen, cherubim, cake, lobster, wifie, Daisy, and her little jew [sic]. Gertrude was king, husband, hubbie, Mount fattie and fattuski." They scattered love notes to one another around their house, signed DD and YD (Dear Dear and Your Dear).

"Such bands of steel are forged by sex," writes Souhami, "and Gertrude wrote a great deal about the delights of it with Alice." Gertrude's work included many private references to her love for Alice -- "my delicious dish, my little wife" -- as well as many references to cows, which Steinian scholars have suggested are orgasms, given that, according to Gertrude," cows are between legs" and are given to wives:

I am fondest of all of lifting belly ...

Lifting belly is in bed

And the bed has been made comfortable ...

Lifting belly

So high

And aiming.

Exactly and making a cow come out.

While Gertrude proffered sex in prose; Alice prepared suggestive dishes. In the "Alice B. Toklas Cookbook," she writes, "In the menu, there should be a climax and a culmination. Come to it gently. One will suffice."

Alice's role was to play the midwife to Gertrude's genius, but she also stands as an argument for the idea that midwives, like housewives, are anything but incidental. To her, housekeeping for geniuses was an art in itself:

I must say that you can not tell what a picture really is or what an object really is until you dust it every day and you can not tell what a book is until you type or proof read it. It then does something to you that only reading can never do.

Besides dusting the art, Alice spent quite a bit of time transposing art onto ordinary household objects. Dishes for artists were a frequent necessity at 27 rue de Fleurus, and a key element of the "Alice B. Toklas Cookbook," Alice's collection of recipes and the stories behind them, published after Gertrude's death.

A culinary work called bass for Picasso was poached in wine and butter, following the advice of Alice's aunt, who contended that a "fish, having lived its life in water, once caught, should have no further contact with the element in which it had been born and raised." The fish, once poached, was covered in "ordinary mayonnaise," then decorated with a red mayonnaise, "not colored with catsup -- horror of horrors -- but tomato paste" and topped with sieved hard-boiled eggs, truffles and finely chopped fines herbs.

Picasso, though impressed by the beauty of the fish, said that it should have been made for Matisse, not for him. Nevertheless, he rewarded Alice's artistry with a needlepoint pattern, which she used to make tapestries for two Louis XVI chairs.

And of course Alice, in the classic role of an artist's lover, served as Gertrude's muse. But given that Gertrude's art was not of the classic genre, this could take the form of not-so-classic endeavors. One guest remembers watching Gertrude instruct Alice to bat a -- what else? -- cow from one side of a field to the other, while Gertrude sat writing on a campstool.

At some point, Gertrude suggested that Alice write an autobiography. Her suggested titles illustrate her ideas about Alice's status in their relationship: "My Life with the Great," "Wives of Geniuses I Have Sat With," "My Twenty-Five Years with Gertrude Stein." Finally, it was decided that Gertrude, not Alice, was to wear the sole pair of writing pants in the family and that Gertrude would write Alice's autobiography for her. Here she is, writing as "Alice":

I am a pretty good housekeeper and a pretty good gardener and a pretty good needlewoman and a pretty good secretary and a pretty good vet for dogs and I have to do them all at once and I found it difficult to add being a pretty good author.About six weeks ago Gertrude Stein said, it does not look to me as if you were ever going to write that autobiography. You know what I am going to do. I am going to write it for you. I'm going to write it as simply as Dafoe did the autobiography of Robinson Crusoe. And she has and this is it.

For Gertrude to write the autobiography of Alice in Alice's "voice" could be construed as sheer hubris. And the novel, which begins with their first meeting and ends with Gertrude's decision to write the autobiography, certainly implies that Alice's life begins and ends with Gertrude. But it is also a love poem of the deepest kind -- an attempt to literally become her lover. (For what it's worth, friends who knew them both say that Gertrude faithfully reproduced Alice's verbal tics and quirks.)

Besides, there is evidence that Alice had quite a bit of power herself, albeit power of the sneakier, passive-aggressive variety. She served as Gertrude's amanuensis and editor. She typed all of Gertrude's manuscripts, making editorial suggestions, and -- since she made the astonishing claim that she read Gertrude's writing better than Gertrude -- perhaps rewrote entire passages.

In the published version of the autobiography, "Alice" says (about Gertrude's "The Making of Americans"): "She wrote it and I typed it. It was over a thousand pages long." Whereas in Gertrude's handwritten manuscript it reads: "She wrote it and I typed it. It was over a thousand pages long and I loved every minute of it."

Hemingway, for one, argued that Alice was the one in control, and that her means of coercion were less than pleasant. He writes in "A Moveable Feast" about a conversation he overheard between the two women which took place shortly before he severed contact with the Stein-Toklas household. First, Alice was heard talking in menacing tones:

Then Ms. Stein's voice came pleading and begging saying, "Don't pussy. Don't. Don't, please don't. I'll do anything pussy but please don't do it. Please don't. Please don't pussy."

But then again, Hemingway had something of a rivalry with Alice. He says of Gertrude: "I always wanted to fuck her and she knew it and it was a good healthy feeling and made more sense than some of the talk."

Aside from their identity as a committed couple in the world of avante-garde art and literature, Gertrude and Alice were in many ways deeply conventional, even chauvinistic. Quite a few Parisian lesbians balked at various aspects of Gertrude and Alice's marriage. Natalie Barney, the writer who held one of the most famous lesbian salons in Paris, believed that her own promiscuity was preferable to their stodgy domestic existence. (Gertrude and Alice in turn, could be smug about their own commitment in the face of the musical-chair romances that governed the bedrooms of Barney, Picasso and Hemingway.)

And author Djuna Barnes was furious when Gertrude, rather than commenting on her writing, said she had beautiful legs. Adrienne Monnier, owner of La Maison des Amis, and Sylvia Beach, owner of Shakespeare and Co., themselves a couple for 38 years, took issue with the infamous treatment at 27 rue de Fleurus of visiting wives, who were expected to talk of hats and cuisine with Alice while the men and Gertrude held forth on literature. Any woman who dared stray into the men's conversation was soon dragooned by Alice into the kitchen, or forced to comment on some small household object.

As for children, Gertrude and Alice adopted many. They took in impressionable young modernist writers -- like Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Sherwood Anderson and Paul Bowles (Gertrude suggested that "Freddy" was a better name for him and refused to address him by any other name).

They also had dogs, who mostly sat on the lap of Mount Gertrude. (Gertrude claimed that the rhythm of her dog Basket's breathing taught her the difference between sentences and paragraphs.) The menagerie of canines, little and large, included Polype, a hound who enjoyed eating his own excrement nearly as much as he enjoyed smelling flowers; Byron, named for his sexual interest in his mother and sisters; Pepe; and Basket the First, whom Gertrude insisted be bathed in sulfur water each day. (She also insisted that Paul Bowles put on a pair of lederhosen and run the dog dry while Gertrude called out the third-story bathroom window, "Faster, Freddy, faster!") They also had a cat with a mustache, named Hitler.

With their closest friends, Gertrude and Alice created small nuclear families, at least through the terms which they chose to address them. With Carl Van Vechten, the famous photographer and not-so-famous writer, they formed the Woojums family: Carl was Papa Woojums, Alice was Mama Woojums, and Gertrude, the child savant, was Baby Woojums. During World War I, they adopted a young American G.I., whom they called Kiddie, and who remained in close contact with both women throughout their lives.

As commonplace as Gertrude and Alice's marriage was in its general outline, the detail was, obviously, remarkable. Perhaps the most extraordinary part was the fame. Gertrude and Alice became famous. Stunningly, iconically, rock-star famous.

And, bizarrely, when it happened, the marriage itself became invisible.

"The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, " Gertrude's love letter to Alice, became one of the unlikeliest blockbuster novels of all time. It is possible that the book's astounding popular success had more to do with its cast of characters -- Picasso, Hemingway, Rousseau, Picabia -- and the implication that two Americans were at the Parisian epicenter, than with America's appetite for experiments in modernist literature.

Nevertheless, when Gertrude and Alice returned to America for Gertrude's book tour in 1934, they made the front pages of the major New York papers, and a revolving billboard in Times Square spelled out in lights, "Gertrude Stein has arrived in New York."

Alice, described coyly as Gertrude's "constant companion," appeared in all the published photos with Gertrude. Alice topped her outfits with a feathered chapeau; Gertrude wore a deerstalker cap; each wore a pair of Mary Janes. They were interviewed together in their shared hotel room and recognized by strangers while out grocery shopping.

And yet no one commented on the strangeness of a pair of middle-aged lesbians becoming the media darlings of 1930s America. And when they started to do so -- years later, when Alice was left alone to fight Gertrude's would-be biographers -- Alice refused to speak to anyone who she believed would delve into her lover's private life. She preferred to keep her love as it was, an open secret.

"I am nothing," she said, "but a memory of her."

Shares