Memory is so indelibly bound up in words, the symbols that stand for the objects that make up remembrance. Twenty-five years ago, I spoke a different language in a different country and lived a different life. Yet I have no memory of it. I was just 3 and by the time I was 4, I had been adopted by an Italian-American family living in South Florida, I spoke flawless English and I had neatly forgotten my past. I began rebuilding my identity from scratch.

Twenty-two years later, my mother revealed to me that just before I was adopted, I had been found on the streets, wandering alone with a note pinned to my shirt that read, "Kim, Won-Hee. August 20, 1972." It was handwritten, not in the letters of the English alphabet, but in the calligraphy of Korea, the country where I was born.

Upon hearing this news, the writer in me immediately snatched it up as something to develop and spread around like so much confessional compost. But the little girl in me was scared and a bit sad. Up until the age of 3, I lived with someone -- a guardian? a parent? -- who cared for me. Then, for some reason, I was abandoned.

I could refashion the story to my liking, giving it elements of adventurousness and tragedy, claiming ownership of an exotic past that would never settle into a neat little pile of events and facts. But in reality, my past became an even bigger black box than it had been, for I had always been told that my parents were dead, and now that story was a symbol of mendacity.

One of my adoptive mother's habits is to spring news like this on me, but in a guileless manner, as if she assumed I already knew what she was about to tell me, her mind forgetting that she once colluded to keep certain things a secret. On this occasion, she responded with astonishment when I appeared shocked at her admission. Perhaps as a gesture of consolation, she proceeded to give me a box of official papers, aging documents with seals, stamps and signatures on them. They are all I have to tie me to my Korean past.

All my life I have fought against what I perceive to be normal and conventional, because I have feared that if I did not struggle, my true self, which would undoubtedly be average and nothing special, would begin to show. I was afraid that I would be what novelist Frederick Exley was afraid of being and what drove him to alcoholic insanity -- a fan, someone to sit on the sidelines and cheer for those who take the center stage in life. After my mother told me about my inauspicious beginnings, I clung to the scant details and added them to my ever-changing identity; it was a way of knowing that I, too, had an extraordinary story to tell.

Then I learned, after some journalistic digging, that my situation was not peculiar for the time or place; most children who were orphaned in Korea were orphaned in much the same way I was, since it was essentially illegal to give away children who had existing relatives. The thousands of children who were eventually adopted usually had been left covertly on street corners and in alleyways.

Korean intercountry adoption by Americans and Europeans came into existence because of the Korean war, which also is nothing unusual. In numerous and obvious ways, war makes orphans of many. But Korean adoption was the second and largest wave of intercountry adoption since German and Greek children came after World War II. It was also the most noticeable wave (which I experienced through the racist taunting of my primary school years); the European kids, for apparent reasons, were less conspicuous.

It was almost fashionable to adopt Koreans after the war, much the way adopting young girls from China or children from Eastern Europe is in vogue today, and more than 100,000 kids -- the majority of them female -- are estimated to have made the trek from Korea to the United States or Europe since 1954.

If you visit one of the many Web sites devoted to tracking down and reuniting Korean families with the children they once gave up, you see the emotional damage laid bare. Women who do not remember the exact year they gave birth plead for help in locating their child who may be 26 or 27 and may or may not be living in the Netherlands. Young adults seek out details of their heritage in desperate hope of enlightening themselves about themselves.

Strangely, I have never felt the urge to find my own biological family. I admit that I am a little afraid of such a search, but mostly I am just apathetic. While growing up, I often mentally perceived myself as "white." What surprised me is that in this, I was not alone: A recent survey of Korean-Americans adopted between 1955 and 1986 shows that more than half saw themselves in the same skewed way, describing themselves as Caucasian. Many times I too forgot that my origins lay halfway around the world. But I am not ashamed of my heritage. Over time I have become very proud of my slanted eyes and flattened face, but these traits are not central to my existence or my common bond with society as a human.

When it was my turn to be given up, I was one of the "lucky ones." My note very specifically spelled out my name and my birth date; I spoke full and flawless Korean so that I could communicate my needs; I had been found not long after I was abandoned. My younger, adopted sister, who came into the family two years after me, was one of the unlucky ones. Her note was lost, and no one knows exactly how long she was left to survive on her own, but it was long enough to bow her legs and weaken her bones from malnutrition, to put disease into her gums and to essentially break a young child's spirit.

The lone picture of me taken right before I left Korea for the first and last time, snapped outside of what I assume are the walls of the orphanage, shows me to be a petite girl with remnants of baby fat still clinging to my cheeks, ostensibly healthy and striking an almost military pose, arms stiffly at my sides. My hair has that slicked-down, Louise Brooks "Diary of a Lost Girl" look that is probably common to all such places, and my face has a shine to it. It's as if the photographer asked me to smile for my new parents, and maybe relayed to me that I was going away to America. But, sad and perplexed, I could only give him a mild look of defiant confusion. My picture, so different from my sister's, at least shows that I was not defeated; hers limns out a bleak existence, with her standing forlornly against a white wall. She just looks lost.

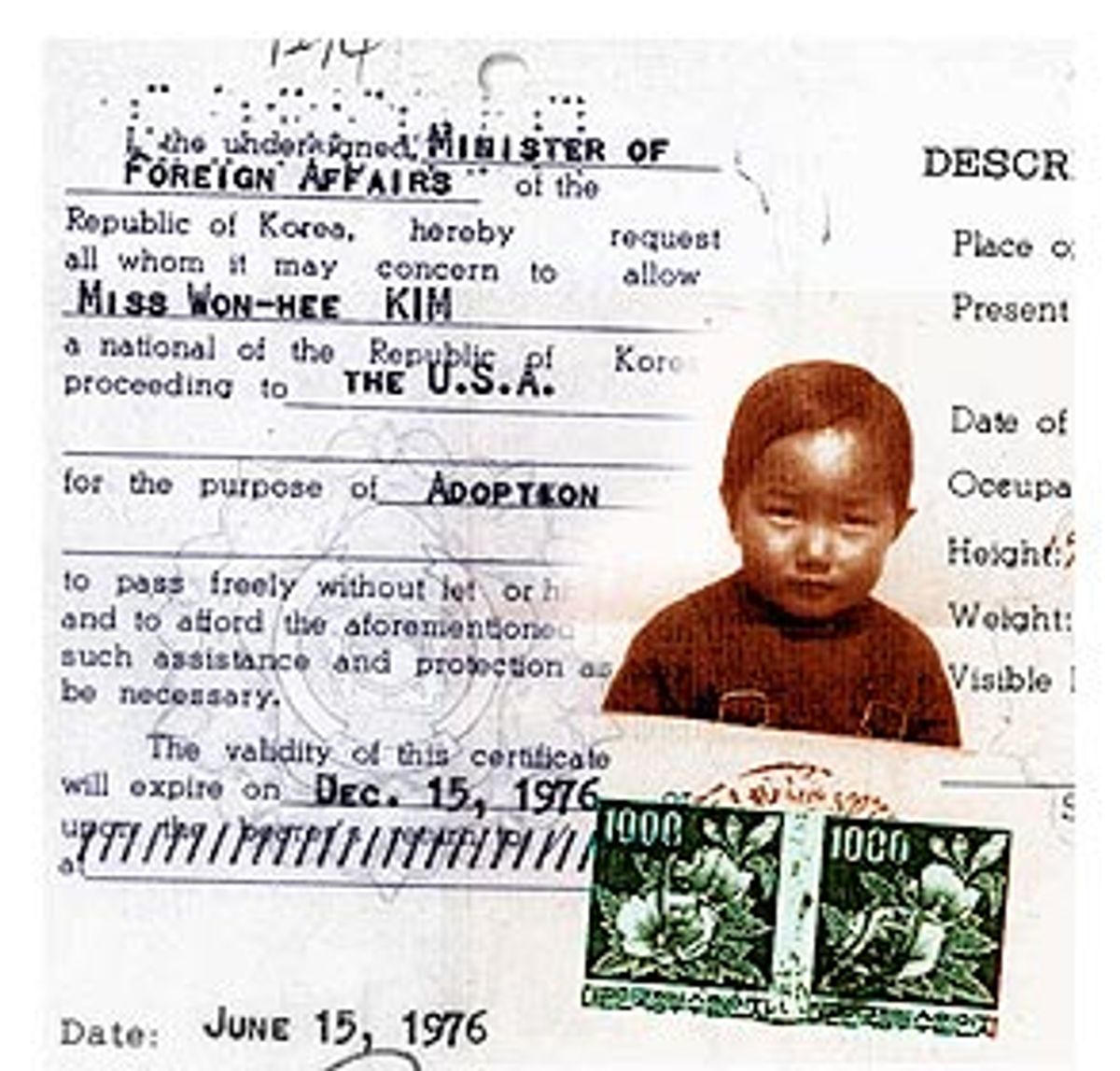

In 1976, I came to New York, literally with the clothes on my back and a single, official "travel certificate," which permitted me "to pass freely without let or hindrance ... for the purpose of adoption." I was approximately 3 feet tall and weighed 28 pounds, only three pounds more than my 10-month-old son weighs now. I am told that I adjusted very quickly, that Korean Social Services, the government agent responsible for my adoption, must have taken good care of me, though I arrived carrying scabies and with a bandage on my forehead. Two years later, almost to the day, my younger sister arrived and I was there to greet her. I felt part of a family once again, and I strove to ensure that she would shortly feel the same.

What I ask now is, why at the age of 3? If I had been left as a newborn, my Korean family would have been abandoning an infant, an almost blank slate, unable to express who she was at this nascent stage. And I can understand the circumstances that may lead a person to do that, such as the financial inability to feed and clothe and take care of a new baby.

But by leaving me at 3, they were abandoning all I had become in those years; they were forsaking me as a young person, a girl named Won-Hee Kim. They were not saying, "We cannot take care of you," but, "We no longer want to take care of you." And I wonder what I was like, what it was about me that caused this action, since in our solipsistic society, I know in the end it must have been my fault. Like a child of divorce, I fear the blame rests on my shoulders, even if, rationally, I know it's likely they just wanted a better life for me, and saw America as a shining beacon.

On this side of the world, I had a ready-made family waiting: a 12-year-old sister, two parents, two sets of grandparents, one aunt and her son. When you meet me, you meet all of them, imbedded within my personality. Most noticeably, I talk with my hands and stuff food down people's throats. Yet I believe in the theory of evolution, having studied it for nearly seven years, so I know that the nuances of my personality were predisposed before I was walking and talking, before any environmental influences had time to take hold. But we all know that a person develops as a confluence of nature and nurture, so I wonder: What behaviors do I have that are a remnant of my first three years of life? What still connects me to that far and distant country?

One thing I know is that I don't have a solid foundation in myself. I never quite know where I belong, and this I definitely attribute to my chaotic beginnings. Like many people, I have always felt isolated and apart, trying a bit too hard to find my rightful place in the group. But my new knowledge of my initial start in life has helped me to reconcile this aspect of myself, putting a cause before the effect, showing me that my rootlessness does not come out of nowhere.

I occasionally wonder why my mother adopted two Korean girls to begin with. When I ask her, she will respond, "Because I love children and would've adopted dozens more if I could have." Yet I look around and see her slightly improper infatuation with all things Asian and the picture on the wall of a birth daughter that she lost at the age of 3. If I ask her about the Asian fetish, she swears up and down that she is not obsessing, but that she was one of us in a past life. She just knows it. By this I am to understand that she has an unspoken kinship with Asians, even though she won't eat bean curd or shrimp heads.

When we talk about the death of her second biological daughter, Diane, she claims the loss had nothing to do with our adoption and the coincidental age of 3. She would have adopted anyway, she says, because she wanted a houseful of children and planned on sending for two boys after Diane was born -- before she found out that Diane suffered from the rare genetic disorder that would kill her. Though I can't help wondering what subconscious motives lay about, when I see her loving and familiar face, the one that has been with me for 25 years, the one that has never abandoned me, I neatly forget all that.

Unquestionably, I am happy to be here, and I am happy to have become the person that I am. The recent turn of events, the attacks on the World Trade Center and the newfound insecurity that has befallen us as a nation, have only cemented my identity as an American and in an ironic emotional twist, left me more secure than ever as to who I am and where I belong. Since I am an Italian-American Korean from New York, I have an immigrant's appreciation of America, but also now an American's appreciation of America.

I have never doubted who my "real" mother is. (Ironically, four years after I came to America, my adoptive father left, so he is a somewhat nonentity in my life.) But now I have a son of my own, and my mind more and more wanders over territory littered with terms that purvey a sense of a knowing past, like "family medical history" and "genealogical tree." My curiosity about my roots has increased a thousandfold so that I am compelled to seek out more knowledge of my other short past, but from a safe and objective distance. I am not yet to the point of looking for my birth parents, and I may never be.

I consider myself a survivor of all that has been heaped upon me through no volition of my own, no different from the rest of society, moving from one event to the next, whether good or bad. I mean, I don't carry around many emotional bruises from these humble beginnings. I adapt quickly. My sister slept with a bag of bread, among other things, for years, while my only visible scar, if it can even be attributed to the healing of a wound, was my use of a night light throughout my teenage years. Really just a carry-on, not true baggage.

But I still like to sleep with the lights on, perhaps to make sure that I won't be left alone in the dark once again.

Shares