In the introduction to her new book, "Harmful to Minors," Judith Levine writes, "In America today, it is nearly impossible to publish a book that says children and teenagers can have sexual pleasure and be safe too."

And once you publish such a book in America today, she can now add, it is nearly impossible to escape the wrath of those who believe that such a statement is nothing less than dangerous.

Since the publication of her book, which is subtitled "The Perils of Protecting Children From Sex," Levine has been set upon by a mob of furious critics, many of them of the opinion that the author, in at least one chapter of the book, has endorsed pedophilia. It is a predictable response, coming in the midst of general panic about child molestation by the clergy, and a Supreme Court ruling last week that reverses a ban on virtual kiddie porn. But it is also a groundless and inflammatory claim that Levine, a self-described expert in "the sexual politics of fear," does not find surprising.

If the process of researching the book -- which includes a look at campaigns against sex-positive thinking -- didn't prepare her for the firestorm following its publication, says Levine, certainly the experience of trying to get the book published gave her a hint of what was to come.

"Harmful to Minors" was rejected by many major publishing houses: One editor called the contents "radioactive"; another said that the timing "couldn't possibly be worse"; another asked her to remove the word "pleasure" from her introduction. And once the book was finally picked up by the University of Minnesota Press, it was the target of a campaign spearheaded by the conservative right to keep it from being published altogether.

Levine's book reached the shelves just as the sexual abuse scandal was enveloping the Catholic Church, a coincidence that spurred the author's detractors to focus on a single chapter in the book that questions the motivations behind "age of consent" laws. Levine suggests that the laws -- which define a "child" as a person 18 or younger, depending on the state -- fail to consider the complexities of adolescent sexual relationships.

Age of consent laws are made, writes Levine, by lawmakers who fail to "balance the subjective experience and the rights of young people against the responsibility and prerogative of adults to look after their best interest." Also in this chapter, Levine questions why teens continue to be prosecuted for having consensual "adult" sex at the same time that, in the area of violent crime, "children" as young as 11 are being prosecuted as adults.

The furor about "Harmful to Minors" began when conservative radio talk show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger denounced the book on the air. An associate of Schlessinger's, Judith Reisman, had brought the book to Schlessinger's attention, claiming that Levine was another in a long line of "academic pedophiles," who were trying to make pedophilia more acceptable. Reisman also alerted Robert Knight, director of the Culture and Family Institute at Concerned Women for America, who called the book "very evil," and launched a campaign on the CWFA Web site, asking Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura to halt publication of the book because it had been published under the auspices of the University of Minnesota.

In fact, nothing in Levine's book suggests that the author condones pedophilia. ("No sane person would advocate pedophilia," she said in her interview with Salon.) And, as it turns out, Reisman and Knight have admitted that they hadn't actually read much of Levine's book before they decided to campaign against it. (Reisman told the New York Times, "It doesn't take a great deal to understand the position of the writer. I didn't read 'Mein Kampf' for many years, but I knew the position of the author," while Knight told the same reporter that he had "thumbed through" the book.)

Of course, had they read the whole book, Reisman and Knight probably would have found ample reason to raise the conservative alarm. Levine takes abstinence-only sex education to task, arguing that it limits crucial discussions of contraception and abortion, while depriving teenagers of information they need to have safe sex. Indeed, says Levine, the programs, which are enthusiastically endorsed by conservatives as well as the Bush administration, frequently put teens at greater risk of harm. If abstinence is presented as the only "surefire way" to prevent pregnancy and STDs, she says, students get the impression that "birth control and STD prevention methods don't work." The result, says Levine, is that students in abstinence-only programs are 70 to 80 percent less likely to protect themselves when they do have sex, compared to students who were given accurate information on birth control and condoms.

Pressure from conservative groups has reached past Levine to the publisher, prompting the Minnesota Legislature to ask the University of Minnesota Press to submit to a process in which it must disclose how books are acquired, and the details of each book's peer review. (Levine's book was reviewed by five outside scholars, instead of the usual two.) Lining up to defend the book are a number of civil liberties organizations and book publishers, including the American Association of University Presses, the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression, the Association of American Publishers, PEN American Center, the Boston Coalition for Freedom of Expression, the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Office of Freedom of Information at ALA and the Freedom to Read Foundation. All have signed a petition condemning censorship and supporting Levine and the University of Minnesota. Regardless of the outcome of these debates, publicity surrounding the book seems likely to boost sales. The first print run of 3,500 copies has sold out, and the University of Minnesota Press has decided to print an additional 10,000 copies. And the book hit No. 27 on Amazon rankings before its official publication date; as of today, it was No. 54.

Levine, who says in retrospect that she's glad she didn't include an author photo on her book jacket, spoke to Salon from her home in Brooklyn, N.Y., about the book's critics, Britney Spears, virginity pledges, what really helps in stemming teen pregnancy and AIDS and the inevitability that each generation will believe its children are being corrupted more than ever before.

You've been accused by the conservative right of advocating pedophilia. How do you respond to that?

The first thing I have to say is that no sane person would advocate pedophilia. It seems ridiculous to me that I have to say that: It's a "When did you stop beating your wife?" kind of question.

Your readers might be interested to know what else the Concerned Women for America are campaigning against, besides me. They are against teaching what they call the "lie" of evolution in the schools; they're worried about the "homosexual agenda" of the Bush administration evidenced by the appointment of members of the Log Cabin Republicans, the gay Republican delegation. They are really incensed about the United Nations' Sustained Development Conference, which they said was promoting the "special agendas" of a number of things, including preservation of the world's ecosystems and human rights. So that's all I'd say about my detractors.

Their critique of your work seems to be based in a reading -- perhaps a misreading -- of the part in your book that deals with age of consent laws. I'd be interested to know how you arrived at the arguments you make for abolishing age of consent laws, and how that would apply to the pedophilia controversy plaguing the Catholic Church.

What age of consent laws are about is criminalizing consensual relationships. Statutory rape is the prosecution of a consensual sexual relationship; if it were non-consensual, it would be prosecuted under regular rape laws, which, I am here to say, are the greatest thing in the world.

What I say is that it is possible for teens to tell the difference between coercion and consent, and that most statutory rape prosecutions have to do with conflict within the family over the sexual lives of their children, most often their teen girls or gay boys. Trying to adjudicate or deal with those conflicts in the context of criminal law -- which only recognizes a perpetrator and a victim, guilt and innocence -- is really a primitive instrument for trying to figure out how young people can have relationships of true consent.

The priest situation is a perfect example of how sexuality always exists inside a culture. It can be a local culture like the Roman Catholic Church, or it can be a national culture, like Afghanistan. In that culture, you have secrecy about sex, you have prohibitions against homosexuality, and, most important, you have the requirement of complete obedience to authority. Those would be among the worst conditions under which any person, young or old, could be involved in a truly consensual relationship. The most important thing to look at is the conditions under which a person -- whether adult or teenager -- engages in sexual behavior that may be harmful to that person. It's not sexuality itself that is the problem.

That's also true when we return to the question of statutory rape law: What conditions would allow, say, a teenage girl to negotiate equally in a relationship, any relationship? I think she needs to feel good about her own desires, and also to be able to stand up for her own limits. She needs to have a life that's rich in other things -- like friends, and community and school. In general, young teenagers who have sexual relationships with adults also have other troubles going on in their lives, though it's not necessarily true 100 percent of the time.

The Dutch law has been brought up a number of times, and I've been attacked for saying that I support something like it. This law covers the ages 12 to 16: Anything under age 12 is considered sexual abuse, and above 16 is considered the age of sexual consent. [Under the Dutch law, children between the ages of 12 to 16 have "conditional" sexual consent; i.e. sexual intercourse is legal, but they or their parents can press charges if they feel they are being coerced.]

In the United States, if we were to have such a law, it might not begin as young as 12; we may not say 16 is the age of consent. But the really important principles underlying that law are the two most important principles, in my opinion, that one must consider in dealing with childhood sexuality: On the one hand, it respects that teenagers and young people have sexual desires, and that they can make autonomous decisions about their own sexual expression; on the other hand, it recognizes that children and teens are weaker than adults and are therefore vulnerable to exploitation by adults, so the law also protects them from that exploitation. And of course, that balance will shift depending upon the age of the child.

A lot of the examples you raised in your book of consensual sexual relationships between teens under the age of consent and persons who were considered to be adults, dealt with couples who were not that far apart in age. In one couple, the girl was 13 and her boyfriend was 21; another example you raised was of a 16-year-old girl and her 18-year-old boyfriend. Is there any case in which you would feel that the age difference alone would be indicative of a coercive relationship? Perhaps if the couple is, say, a 13-year-old and a 35-year-old? Or a 16-year-old and a 45-year-old?

There is a social worker named Allie Kilpatrick at the University of Georgia who did very nuanced and in-depth interviews with several hundred adult women about their childhood and teenage sexual experiences. When I asked her this exact question -- "Does age have any effect on their actual experience?" -- she said, "No." Having said that, I would reiterate that if a 13-year-old is having a relationship with a 35-year-old, I would say that that sexual relationship is probably symptomatic of other things going on in that person's life, which is the thing that would be most important to me.

So at that point, would you say that, rather than criminalizing the relationship, you intervene in other ways to break off the relationship, such as by talking to the child, or sending them to counseling?

If I were that 13-year-old's mother, I would intervene, yes. I would be worried about it. Would I be able to stop her if she were intent on doing it? Other than locking her in her room, I wouldn't be able to. But I would hope that I would be able to offer her something of what she is looking for from that 35-year-old. And if not me, perhaps it would come from some other adult in her life.

I think it's obvious that if a young teenager is having an affair with a much older adult, he or she is looking for some sort of a parental relationship more than a sexual relationship. You see this a lot with homeless kids, who have what they call "survival sex," where they trade sex for a shower, or a night in a bed instead of sleeping under a bridge. What they need is that bed, that adult companionship, and that shower.

One of the things I noticed in looking at the comments put out by your detractors is how "dirty" they made your book out to be. Do you see that as symptomatic of how any honest talk about sex is trivialized as being simply prurient?

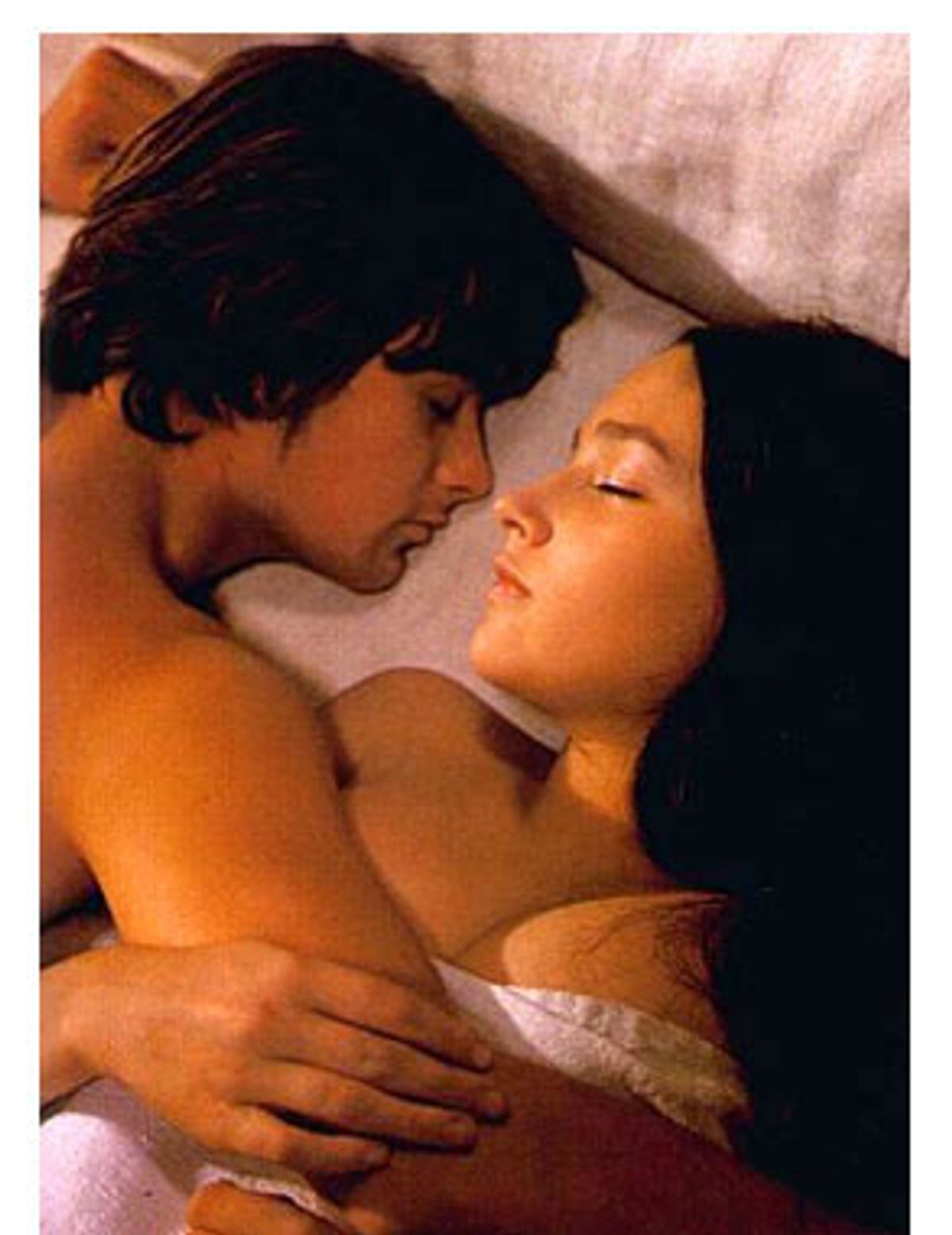

A good example of that is the cover of my book, which shows the bare torso of a child. People have reacted to this book by saying that it is either prurient or pornographic on the one hand, or, on the other, that it is completely innocent. That to me shows that there is no image of a child, or any way of talking about childhood sexuality that doesn't fall into either one camp or the other. The idea that childhood sexuality could be anything but a problem, unless it is altogether expurgated, is something that I frequently come up against.

Another example would be the judges who look at images of a baby in a bathtub and see pornography. My judgment of that guy is that he has a dirty mind!

One of the arguments that we hear quite frequently is that childhood has been "sexualized" by the mass media -- Calvin Klein ads, TV, etc. -- in a different way than it ever was before. Do you think there is any truth to that?

I don't like the word "sexualize" so much. It implies that children wouldn't otherwise be sexual if we didn't subject them to propaganda. We might be comforted by the fact that there has never been a generation that hasn't looked to the media as corrupting its youth. Before there was pornography, there was MTV, and before MTV, there was rock 'n' roll, before rock 'n' roll, there was comic books, before comic books, there was dime novels, before dime novels, there was burlesque. And yet each generation of youth somehow managed to grow up and be morally upstanding enough to decry whatever they felt was happening to the next generation.

As you pointed out in your book, many childhood development experts, such as Dr. Spock, and to some extent, Penelope Leach, were very adamant in labeling sex play as a normal part of childhood. I've noticed lately that people have become more and more fraught over the issue of what constitutes childhood sex play. Some experts even say that sex play itself is a sign that a child has been sexually abused.

There doesn't seem to be any evidence that this generation of children is engaging in any more "sexual rehearsal play" than previous generations. And, as I point out in the book, sexual rehearsal play is so normative throughout the world that anthropologists call it "sexual rehearsal play." They see it as a part of children's sexual development at every age, in every culture, as far back as they've ever studied.

This generation of kids seems to have absorbed a lot of sexual conservatism, even down to their pop heroes, like Britney Spears. Teen pregnancy and teen sex rates both dropped slightly during the '90s, at the same time we're seeing the rise of so-called virginity pledges. Do you think this generation is rebelling by being less sexual than their parents' generation?

The girls who idolize Britney Spears are in the age group the marketers call "tweens." Once they actually become old enough to have sexual desire, I don't think that their idolizing Britney Spears is going to stop them from acting on those desires. In fact, it apparently doesn't even stop Britney.

The drop in teen pregnancy, I would attribute to the use of condoms, and that seems to be what the Alan Guttmacher Institute and everyone else says.

I think that if kids are abstaining, it's mostly out of fear. And it's not simply fear of AIDS and pregnancy. What a lot of kids tell me is that they have this sense, like we did in the early '60s, that any misstep could really mess them up for a long time. It's a sense of huge consequence to anything you might do sexually -- it may do damage to your reputation, or you may have an abortion that you will regret for your entire life. I do think that kids have absorbed, if not so much conservative values, the overall message of conservative teachings, which is fear about sexuality.

Most of the daughters of feminist mothers that I know are not signing abstinence pledges. The people who are signing abstinence pledges are Christian kids. The conservative message is definitely working with young people on the issue of abortion. And I think that pro-choice people have unwittingly aided that by saying that abortion is always a tragedy, that it is really terrible, and difficult to go through.

But it's all just a guess. We really need some data on what kids are doing and feeling and thinking. That would help them, in perhaps educating them better, would help us in perhaps helping to prevent the spread of HIV. But the right has succeeded in shutting down all state funding of such research.

Before the decade in which birth control and abortion on demand were widely available, sex was dangerous; you could irrevocably change your life, or even die from sex, whether from a botched abortion, or an untreated STD, or even in childbirth. And then immediately, within a generation after sexual liberation, in the '80s, with the advent of AIDS, we were returned to a situation in which sex could be lethal.

What would you say to the argument that perhaps the attitudes boomers were raised with, that sex is healthy, that sex can be purely for pleasure, that sex shouldn't be feared, is itself a historical aberration?

I think there is some truth to that, but certain of the changes that happened in the '60s and the '70s through various sexual liberation movements mostly benefited women and gays. What people like Gloria Jacobs, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English said about the sexual revolution was that it was a revolution for women. Men had always done what they wanted to do, and they continued to do what they wanted to do, and I think that is still true for boys.

We're still looking at women and girls. Some of what I consider to be advances of that time -- such as women being recognized as having desire -- have stuck. The right is doing a rear-guard effort to turn that back, but I think it's very hard.

When we look, for instance, at the rate of sexual intercourse for teenage girls, it's now about at the level where it was in 1984, which is right around half -- 54 percent or so. But also history is a little more complicated. For example, in the 1950s, America had the highest rate of teen marriages in the industrialized world.

I love the joke in your book that defines a "conservative" as a "liberal with a teenage daughter." But a lot of boomer parents that I know, while they may realize that they are perpetuating a double standard by expecting their children to practice more conservative sexual behaviors than they themselves did, justify that expectation because they still feel very strongly that sex has changed because of AIDS.

Well, sex has changed because of AIDS. But the question is: What are we going to do about that? A good example is to look at the gay, middle-class urban communities during the height of the AIDS epidemic during the '80s. Their strategy was to use a sexually open culture, a culture of enormous sexual creativity, and lots of public discussion about sex (and even public sex!) [to combat AIDS].

A sexually open community was able, through that very openness, to stem the tide of the infection. Now when we see who is getting HIV, it's people who live in communities that are often repressive about sex, certainly repressive about homosexuality, where people are outside of the institutions where they might be able to get good sexual information.

You point out in your book that a lot of the kind of sexuality education that you advocate -- emphasis on pleasure, open knowledge -- was fairly prevalent throughout the '80s. I found it strange to notice that sex ed seemed to be more informative and open during the Reagan years than it was during the '90s.

There is always a lag between political activism and results. In 1981, the American Family Life Act [which advocated abstinence -- called chastity at the time -- as the basis of sex education in public schools] was put on the docket in the House of Representatives. It was from then on that the religious right began -- in Washington and in local communities -- its very successful campaign against sexuality education. The Reagan administration gave these people a platform that they had never had before, and all of these agencies -- health, education, welfare -- were headed by people who were against sex education.

You had more influence from the religious right in Washington, and a very sophisticated and smart grassroots movement, which often consisted of a tiny minority of people in a community. But many people were complacent, in the same way that I think many people in the pro-choice movement were complacent about abortion rights, and they didn't stand up for sexuality education.

It's a hard thing for anyone in the legislature to, say, stand up for talking about masturbation in school. So you had no defense, and a very strong offense against sex ed. We began to see the results of that later in the '80s, and certainly in the '90s.

Should we even try to continue to keep open sexual education in the public schools, given the near-impossibility of reconciling everyone's politics? Why not send children to outside programs in their community, like Planned Parenthood, who aren't censored by the politics of the community and the school board?

Among mainstream sexuality educators, there has been the suggestion that maybe we should give up on the public schools. I think that's very ill-conceived. Most people will go to public school. It's hard enough for community organizations to fund anything. At least, if there is good education in the schools, every kid will get a little bit of information. But it's also very important to have other sources of information for kids that they can access by themselves -- in the library, on the Internet, etc. And you also have to take care of the vast number of kids who are not in school -- who have dropped out, or are not living at home, or whatever.

There's a big difference between the sexuality education that goes on in mainstream public schools and the education that one would get at a community organization like Planned Parenthood. It's not only because people outside of school have more freedom; it's also because the kind of people who enter those jobs tend to come from an activist, rather than a professional background. Many of them are gay or lesbian, or youth activists. They have a different attitude right from the get-go about sexuality education.

Sex education has a conservative history. It's main goal has always been to stop kids from having sex. Even progressive sex education has often had that as a goal.

In your book, it seems to come out that sex education directed at gay kids might be even better than that which is directed at straight kids, in that gay kids who look to community organizations have adults who are extremely concerned that they have the best resources available.

Yes, well, if only the gay kids weren't getting beaten up in school.

But it is true. One of the things I say in my book is that at least a gay kid comes out as having a sexuality, and thus you have to deal with them as a sexual person. I think the best sexuality education, and the best attention to the whole child and the teen, has often come from the gay and lesbian community.

You can say to straight kids, "Don't have sex until you get married," but if you tell gay kids that they can't get married, there is not much they can do. Actually, I suppose the right is still saying to them, "Don't ever have gay sex until you die." But for those mainstream educators in the middle, to deny the existence of those who might be gay in your classroom is certainly not serving every student's need.

What do you make of the great oral sex scandals of the late '90s? Suddenly every newspaper seemed to have a headline story about oral sex, or sex parties, or how kids today look at oral sex differently than their parents' generation did. I'm sure a lot of this had to do with Clinton, given that they all came out around the same time.

Do you see evidence that children's sexual behavior is shifting toward having more oral -- and some reports even say anal -- sex than previous generations? And if so, is this a response to a fear of sexual intercourse?

The little research that we have shows that kids are doing oral sex, and sometimes anal sex, more. It's still a tiny statistical minority of kids who have claimed to have anal sex, but in the case of oral sex, not only do they do it more than intercourse, and maybe more than previous generations, but to me the interesting part is that they assign a different meaning to it than their parents' generation did.

In my generation, oral sex was something you did with someone you were intimate with. For them, it's less intimate, and vaginal intercourse means more. I remember even in the '70s, in cultures that valued vaginal intercourse very highly, you would hear anecdotes about young women who had anal intercourse and believed that they were still virgins. I think those rumors were highly exaggerated. They didn't come from any real data.

As for the idea that younger and younger teens are engaging in oral sex, there doesn't seem to be any research that shows it's actually happening. It's usually presented in the context of this "one private school" where one 13-year-old girl said that this other girl had oral sex.

Sexual behaviors do change throughout history, and AIDS has had an impact on sexual behavior. It makes sense. If teens are engaging in oral sex mutually, that is, boys doing it to girls, as well as girls doing it to boys, and they were using a latex condom, then it's not necessarily a good thing or a bad thing. My concern is more whether people are doing things that they really want to do, and are not doing it because somebody else said they should. If teens want to have pleasure in sex, it's crucial that they have a repetoire of safe sex behavior.

Of course, girls have a much higher risk of AIDS transmission through oral sex than boys do.

Yes. At the very least, they should use a condom.

Recently, I ran across a story on the wires about a group of 9-year-old boys who were performing oral sex on one another in a public school classroom. Does that test the limits of what you would consider to be normative sex play?

Well, I don't think kids should be having sex in class. Yes, I would say that I am definitely against oral sex in the classroom.

Fair enough. I suppose the more nuanced question, which you deal with in your book, is how do you deal with that? Do you criminalize it? Do you treat them as deviant?

The word "deviant" just means different from the norm. I would say that, in general, criminalizing sexual behavior that is consensual is a bad idea. The thing that I say in my book is that it makes perfect sense to me that if a person is going to act violently in our culture, that sex might be the means with which they do it. We live in a culture in which sex is the lingua franca of just about everything -- of the market, of love, of hate, of everything.

Futhermore, it's very important for kids to learn not to push anyone to do anything they don't want to do. To me, sex is not a separate category of that: You don't hit people, you don't take their toys, you don't force them to give you a dollar, and you don't force them to touch your penis.

If we are trying to teach kids to respect each other, to get along in their community, those are values that we need to inculcate in them in every realm of their lives. I would hope that the sexual would just naturally flow from those values of how you live with, and how you treat, other people.

Some critics have called your book "not parent-friendly." How do you respond to that?

Parents understand that their job is to be able to send their kids out into the world. While they want to protect their children, they are also thrilled with their children's independence. There's no more exciting moment than when your child toddles off on his tricycle for the first time and doesn't look back. It's sad, but it's also exciting. If they feel that they can't do that in the realm of sexuality, I think that's a sad and difficult thing.

I would hope that I'm being helpful to parents, not only in sorting out the real perils from the exaggerated ones, but also in giving them some ideas of the ways in which they, and other people in their community, can help to guide their kids into a happy and safe sexuality.

I did notice that most of the parents quoted in your book sounded like pretty progressive types. There were several gay parents, feminists, academic families. Do you feel a sense of preaching to the choir in that regard?

I don't actually talk only to progressive parents. One mother I talked to, a working-class woman, was the one who was quoted as being appalled when her daughter came home from school [after a "good touch/bad touch" workshop] and said, "Don't touch my vagina, Daddy." But I think you're right that a lot of the parents I talked to were mostly progressive parents. I was using them as examples of parents who had been relaxed about sex, and their kids were OK.

But even those parents had their fears. One very progressive woman I quoted towards the beginning of the book said that she was turning into an "ironclad conservative" about her son and sex, and not about anything else. I also had a conversation with about 12 other parents from her synagogue, which was pretty conservative.

I don't want to minimize the very real dangers that young people face from sex, but I also would like to try to move the discussion of child and teen sexuality out of the realm of "problem." That, to me, is really the crux of it. Progressives do the same thing. They get a grant, for example, to deal with teen prostitutes. And they can't get a grant just to deal with teens.

You seem to advocate a position of open discussion on demand, balanced with a tolerance for children's privacy, even closed doors.

I talk a lot about respecting the sexual privacy of even very young kids. I'm not sure that barging into their room and seeing them masturbate, then sitting down and saying, "Oh honey, let's talk about masturbation," is necessarily the best thing for that kid.

One early childhood educator that I talked to said, "Children need room for sexual transgression outside of adult eyes and outside of adult commentary." I thought that was a smart thing to say. Sexuality is something that is often private. As long as kids know that if something is hurting them, they can talk to you, or to some other adult, I think we need to respect their privacy.

My mother worked at a birth control clinic, and she would leave out books. And I always felt that was intrusive too; there was nothing she could do that was right.

Does that right to privacy extend into the teen years? Should parents still respect the privacy of their children behind closed doors, even with their lovers or potential lovers?

My parents did. During the sexual revolution, I did a story talking to parents about how they felt about their kids' sexuality. A woman told me a story about her 15-year-old daughter, who said, "Mom, I want my boyfriend to sleep over at home." The mother said that she felt that if the daughter was asking for her permission, she was also in a way asking for her participation. She said it almost made her feel as if her daughter was not ready to have sex, if she needed her mom there. That sounded wise to me. Sexuality is a way of moving away from your family, it's about forming intimacies outside the family; it really is not about the family, it's about the not-family.

This woman said to me, "Would I rather she were out under a bridge having sex than on the Upper West Side in my apartment? No, I wouldn't." But by the same token, in France it's very common for a teen's boyfriend or girlfriend to sleep over. I do think that teens are much more likely not to want to do it in the house when their parents are home, just as parents don't like to do it when their kids are listening. These are issues in which a hard and fast rule is not adequate. The aim of the right is to try to simplify what are very complicated issues.

When I gave my book to my mother, I inscribed it: "Thanks for teaching me the difference between right and wrong." And I feel my mother did that. But she also left me room to explore my sexuality. And as a result, I made some mistakes, and I recovered from them. But I do think what she and my father gave me were the tools to make good decisions and to be a moral person in the world, and that stood me well.

Shares