Lying in his sparsely decorated hospital room, Juan Torres looks like any patient in any hospital. Most days, he whiles away his time away watching cable TV or flirting with the nurses, who sometimes order him pizza to boost his spirits. A car accident in April nearly killed him. His pelvis was crushed, and he's still unable to walk. A 3-inch pin holds his right arm together and a deep red scar stretches across his forehead.

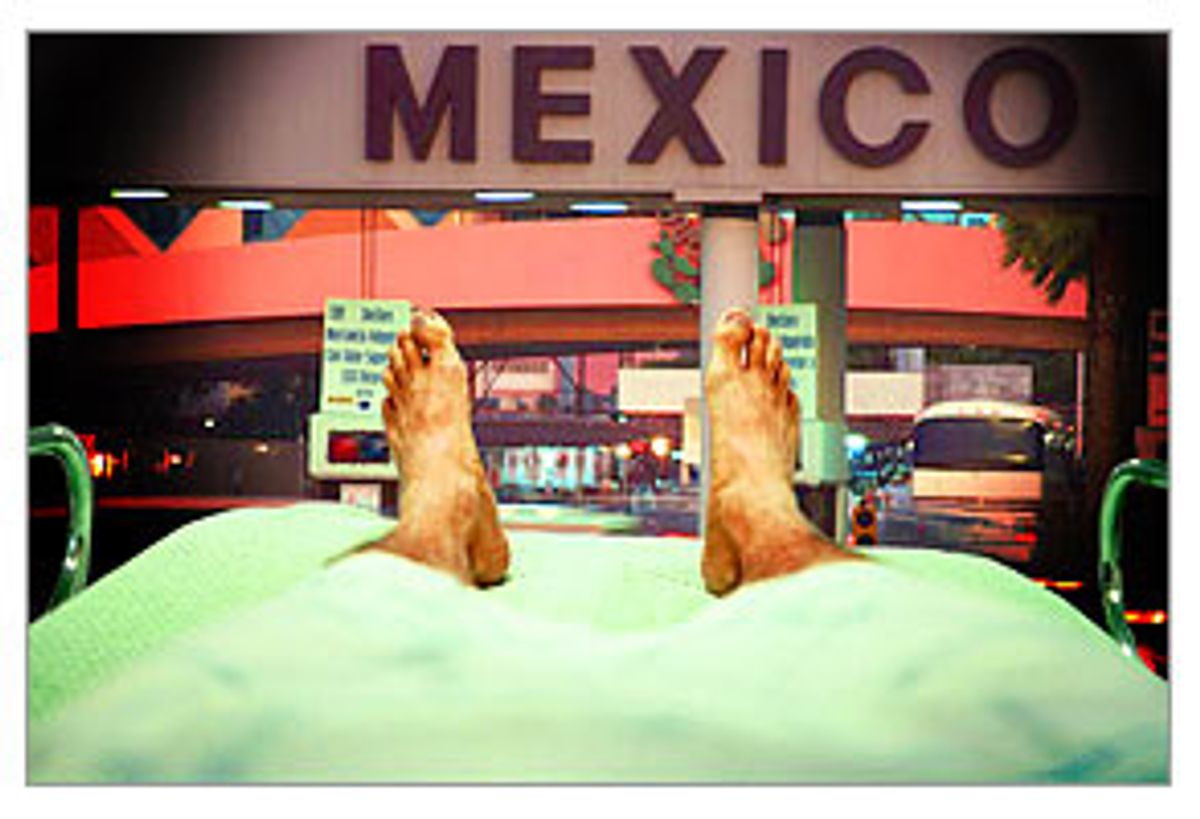

But Torres, a gawky, poker-faced 27-year-old, isn't like most other patients here. In fact, his hospital stay came with an unexpected twist: a cross-border trip to this bustling city. Torres' car accident actually happened 100 miles north in the U.S., on the California and Arizona border. He spent the first two months recuperating in a hospital outside San Diego before the hospital there offered to transfer him to Tijuana to finish up his recovery.

At the time of the accident, Torres was earning $40 a week picking melons and grapes and living mostly in migrant farmworker camps. But as his days in the hospital turned to weeks, and the severity of his injuries became clear, Torres began to worry: he had neither a place to live once he got discharged nor anyone to help him get back on his feet. When could he work again? Who would pay for his rehabilitation? Like most illegal immigrants, Torres didn't have health insurance and his hospital bills were piling up fast.

Then, one morning in May, a caseworker at his hospital, Scripps Memorial, stopped by Torres' room with an idea. She told him that the hospital had recently started contracting with a local company that had a medical facility in Tijuana. Scripps would help transport him, pay all his bills and even pick up the tab for a plane ticket back to his hometown, Oaxaca, once he was better. Torres' caseworker explained that the quality of care in Mexico would be excellent and that he would be able to get the months of rehabilitation he needed.

Torres jumped at the offer. This way, he could be closer to home, and he wouldn't have to worry about his bills or being reported to the INS.

Two days later, Torres signed a three-paragraph transfer agreement and took a half-hour ambulance ride over the border to Hospital Ingles, a two-story, 17-bed facility on a busy street in downtown Tijuana. He's still there today, and he'll likely stay for several more weeks until he is healthy enough to travel home. "I am grateful for what everyone has done for me," says Torres, looking well, if a bit uncomfortable, as he sits up in his bed. "I have no regrets."

The outfit that orchestrated Torres' Mexican homecoming is NextCare, a Chula Vista, Calif.-based company founded by a retired medical salesman, Bob Barraza, 58, and his 49-year-old partner, George Ochoa, who moonlights with NextCare on the side from his day job as the director of diagnostic services at one of Scripps' five local hospitals. While some hospitals across the country have also tried sending undocumented patients home in recent years -- mostly as one-off attempts in which nurses accompany an uninsured patient home -- NextCare appears to be the first company in the country trying to make a business out of the practice.

Ochoa and Barraza were business acquaintances for nearly a decade before they founded NextCare in 2001. Ochoa, who saw the strain that uninsured illegal immigrants were putting on hospitals like Scripps, decided that there was a business opportunity in arranging for immigrants arriving at border hospitals to return to Mexico for their care.

The numbers made perfect sense. Because Mexico has a quasi-national healthcare system, medical costs there can be a third of what they are in the U.S. Patient bills that run as high as $2,000 a day in the U.S. cost just a third of that in Mexico. While the company won't discuss financial arrangement with partnering hospitals, the standard deal works something like this: a typical acute-care patient in a U.S. hospital costs around $1,500 a day to treat. NextCare charges the U.S. hospital $1,000 a day to transfer and care for the patient in Tijuana. Hospital Ingles charges around $400 a day to treat the patient. And NextCare makes a profit off the difference.

At first, the company admits, it was hard getting hospitals in the U.S. on board. Some had to get over their initial "ick factor," says Barraza, worried that program might appear as though it was taking advantage of the helpless. "No one wanted to see their face on '60 Minutes,'" he says.

But then NextCare invited administrators and doctors from Scripps and other area hospitals to visit Hospital Ingles for a tour and to meet the clinic's owner. After seeing the facility and speaking with its director, says Next Care, the group of three doctors and a representative from the Mexican Consulate were sold. "It's a "top-notch facility with excellent doctors," says Dr. Brent Eastman, chief medical officer at Scripps Health.

So far, NextCare's efforts are paying off. In the past 18 months, they've signed up seven San Diego area hospitals and treated 65 patients, a number they hope will rise in the coming year as they sign up other hospitals in Orange County and Los Angeles. And as early as next year, the company hopes to triple the number of beds at Hospital Ingles.

Not surprisingly, NextCare has plenty of critics. Many compare what the company is doing to medical deportation -- a fast and loose way of making money off people who are scared of possibly being arrested and don't understand their rights. Dr. David Goldstein, co-director of the University of Southern California's Pacific Center for Policy and Ethics, says that enticing undocumented patients to leave the U.S. while they lie in a hospital bed just weeks after suffering serious injuries, and often while still on medication, doesn't even pass the most basic ethical litmus tests. "For doctors, the first rule is do no harm," he says. "I'm not sure that's the case here."

Complicating matters further is the fact that many illegal immigrants in the U.S. have little or no formal education -- and according to the Urban Institute, a nonpartisan economic and policy think tank, a quarter of Mexican immigrants cannot read. This worries some immigration advocates who fear that patients may not fully understand their rights when it comes to being transferred.

"Most of these people are too scared and unaware about their rights to be making such an enormous decision," says Gabrielle Lessard, staff attorney at the National Immigration Law Center in Los Angeles.

Lessard adds that it may be possible that the hospitals working with NextCare are violating federal laws that mandate that all patients receive similar medical treatment regardless of race or immigration status. While Lessard admits it's hard to prove a hospital is breaking the law, she believes they are essentially giving different medical treatment to undocumented patients by singling them out to return to Mexico before they've fully recovered. In fact, recent NextCare cases include a double amputee who was sent to Hospital Ingles two weeks after his accident and a quadriplegic who was moved to a charity hospital for long-term care about three hours outside Mexico City after spending three months at Hospital Ingles.

NextCare and its partnering hospitals counter these charges saying that what they are doing is in fact a godsend for most patients. They point out that while uninsured patients can't legally be forced to leave a hospital until they agree to leave, many are discharged once they can walk out the door on crutches. Only those that complain -- or are aware of all of their rights -- usually stay and finish out their full care.

NextCare and the hospitals also insist they are abiding by all laws and going to every length to ensure that patients fully understand their legal options before making any decision. In some cases, the Mexican consulate oversees the process to ensure the patient is treated well. "We only approach patients after they've passed their acute phase, and they are fully aware of what they are doing," says Rosemelia Lopez-Platt, Scripps' coordinator of international services. "We are clear with them they don't have to go if that is not what they want to do."

However the legal and ethical arguments play out, hospitals like Scripps say they're running out of options. An unprecedented wave of illegal immigrants -- according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the annual number rose from 3.5 million to 7 million in the decade from 1990 to 2000 -- are showing up at emergency room doors, often with severe and expensive injuries. Although Scripps' system of five area hospitals runs a profit, the company bleeds $7 million to $10 million annually at Scripps Chula Vista, its closest hospital to the border -- a good portion of which is lost on uninsured patients.

By law, hospitals must treat and stabilize anyone who comes though their doors. But neither the federal government nor any of the border states most affected by illegal immigration -- California, New Mexico, Texas and Arizona -- have helped pick up the tab. "At some point, something has to give," says Ms. Lopez-Platt of Scripps.

A survey done last year by the U.S.-Mexico Border Counties Coalition, a lobbying group for 24 U.S. border counties, estimates that border hospitals are losing $200 million annually on undocumented patients. Congress is currently considering a bill to reimburse border hospitals $410 million a year for the next four years as part of the massive Medicare legislation under consideration.

In the meantime, one of the only measures border hospitals say they can take is to send illegal immigrants back home. NextCare helps hospitals with the task by promising the same level of care for patients -- if not better, they say -- in Mexico. They also entice patients with comforts like fresh Mexican food, Spanish-speaking doctors and nurses and visits from family who can more easily travel to Tijuana than to the U.S. Some even receive psychological counseling to help sort through the effects of their trauma. According to NextCare, up to 85 percent of patients they approach decide to make the transfer to Mexico.

Back in his small white hospital room -- complete with Spanish cable TV and a nearby bookshelf full of movies -- Juan Torres says he couldn't be happier about coming to Hospital Ingles. He's satisfied with the progress he's making, and says his doctor and nurses are wonderful. Listening to him rave about his care, it's easy to wonder if the company's plan to treat patients in Mexico may indeed be a perfect antidote for overcrowded border hospitals.

But underneath Torres' platitudes are some disturbing details. For example, he says that the day his caseworker told him about the NextCare option, he was "still dazed from the accident" and on heavy pain medication. He also acknowledges that he wasn't aware that he could have had the same treatment, including long-term rehabilitation, if he insisted on remaining in the U.S. Knowing that now, is he bothered? "No. I'm happy here," he says.

A spokeswoman for Scripps says Mr. Torres was clearly made aware of all his options before he signed his transfer agreement, and that he was coherent during all conversations about his transfer. For its part, NextCare says it is not concerned about the fact Torres may have made his decision while heavily medicated. "That's not our responsibility," says Barraza. "It's the hospital's responsibility to take care of that stuff." (Later, the company amended that comment, saying they do try to make sure all patients are aware of their rights before they agree to leave).

Meanwhile, Juan Torres is counting the days until he can walk out of Hospital Ingles unassisted and fly to Oaxaca to see his family. Though because there are so few jobs there, he probably won't stay home for long. "Who knows?" he says with a smile. "I may try to come back to the States."

Shares