St. Luke's Episcopal is a small red-brick church that stands shaded at the corner of two tree-lined streets, not far from the main square of Auburn, Calif. In a town of many churches it is the second-oldest one, and its congregation, like the town, is almost entirely conservative and white. In St. Luke's, an American flag hangs over the pulpit, and nearly every Sunday of late there are family members in Iraq to pray for listed in the bulletin. At service, there are men who lean heavily on their canes when the congregation is called to stand, and white-haired women nearby whose help the men refuse. After the sermon they all give thanks for the blessings in their lives, and sing.

One recent Sunday, newlyweds Jean and Toby Adams walked to the altar and held hands. The women had been married two weeks before, but not many in the congregation knew that yet. This was Jean's first time in Toby's church, and because she had grown up in a similar congregation in small-town California she was cold with sweat on her way to the altar. The 10 or 12 steps to the front of the church seemed long to her, but when they arrived and turned to face the congregation, Toby was clear voiced and calm. "I would like to give thanks for our marriage," said Toby, and stopped. There was a pause as the senior warden hurried over to them, turned to the congregation, and took Jean's free hand. "Let us give thanks for how open our church is," he said. Only one couple left the church as a result.

Since its founding in 1887, this was the first time St. Luke's had ever had a same-sex marriage proclaimed within its walls, and no one knew how the parish would react. This is not a church used to change; when they received their first female priest, this year, they decided to call her Father Marcia because they didn't know what else to call a woman priest. Still, the recent votes by the national Episcopal convention to approve the first openly gay bishop and to allow the blessing of same-sex marriages mean that St. Luke's is now faced with a challenge far more controversial than what to call female priests. While most of the congregants like Toby and Jean, some worry about the legal and religious changes the two might come to represent. "Up until now there's been kind of a don't ask, don't tell policy," says Toby, "and with the ruling that's changed."

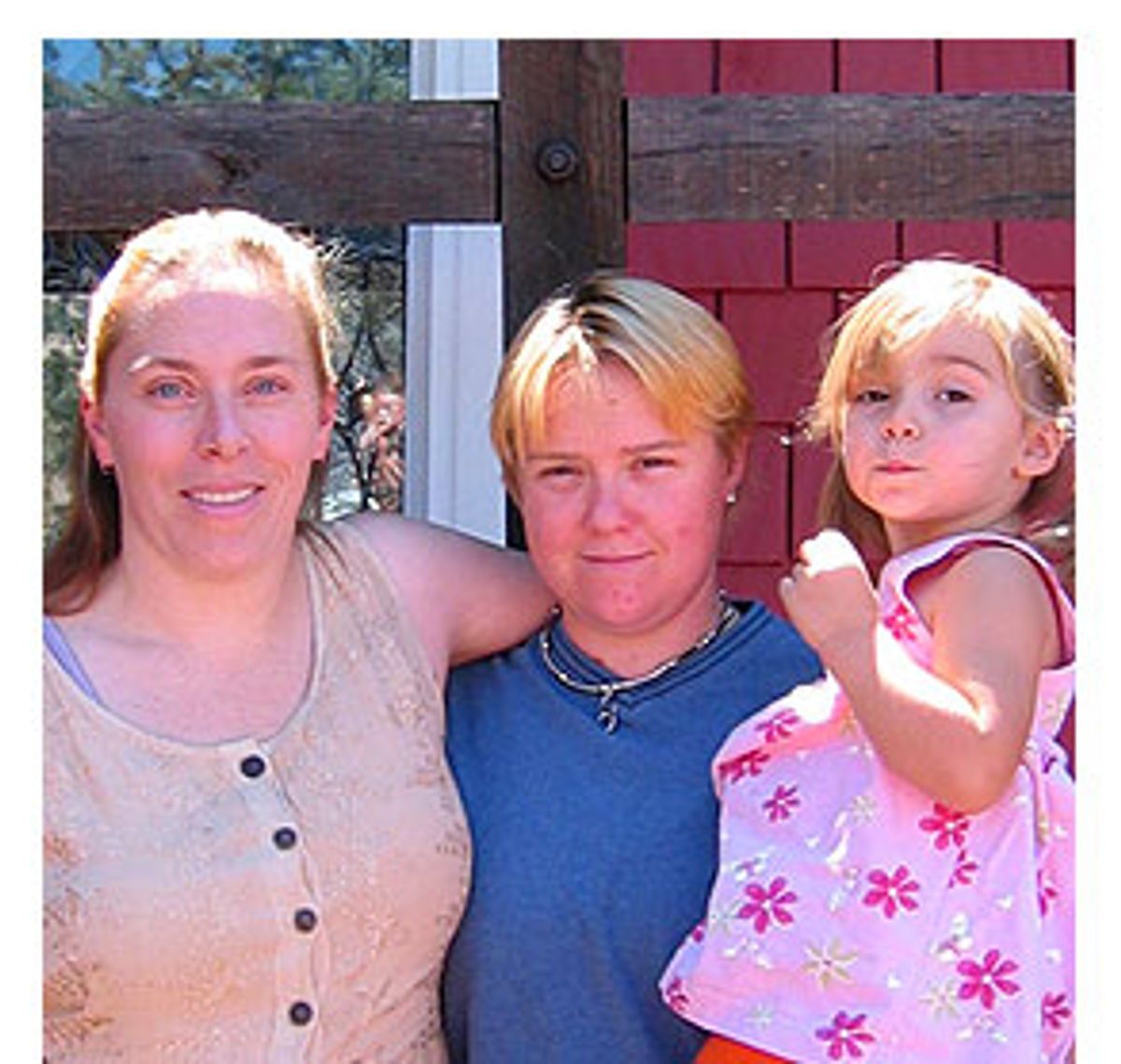

Though Jean and Toby Adams didn't move to Auburn with their 3-year-old daughter Kalen to make a political statement, in the year they've lived here their very presence has done it for them. They weren't married legally -- there are no states that officially recognize same-sex marriage -- but in their daily lives they still live quietly and openly as wife and wife: at church, in the neighborhood they live in, at the preschool attended by their little girl. In many ways the Adamses are the all-American family -- Toby, 37, a software project manager, and Jean, 30, a remedial writing teacher for adults -- and if one of them were a man, their neighbors would probably regard them as model parents. Instead, people who've lived in the town all their lives are planning to move now that a same-sex couple lives down the block; others cheer the women on. As for the majority, they just don't know what to make of the Adamses yet -- but as time goes on, they're going to have to decide.

Like other small towns across the nation with low housing prices and good schools, Auburn is an attractive place to raise a family. It has the look and feel of an Old West town, but it's also close enough to Sacramento and San Francisco to have a few cosmopolitan flourishes. And as same-sex couples increasingly demand -- and win -- rights similar to or the same as those taken for granted by heterosexual couples, more of them are seeking the quality of life offered by the heartland. The mixed response that Toby and Jean Adams are finding is, perhaps, emblematic. For other small, conservative towns across the country, Auburn is either a beacon of hope or a warning siren.

There are a number of places in the United States today where a gay couple pushing a stroller is considered unremarkable, and if you live in such a place long enough it's easy to believe the United States will soon follow Canada's lead in legalizing same-sex marriage. Hawaii, Vermont and California all grant some legal rights to domestic partners, and this fall the Massachusetts Supreme Court is poised to hand down what many believe will be a decision to legalize same-sex marriage rights across the state. But as the number of states recognizing same-sex unions grows, so has the backlash, and now a coalition of right-wing Christian groups has vowed to end the struggle once and for all -- through a constitutional ban.

Sponsored by 70 House Republicans and backed by the ultra-conservative Family Research Council and 24 other Christian groups, the Federal Marriage Amendment would legally define marriage in the United States as consisting "only of the union of a woman and a man." If passed, it would nullify every current state law granting same-sex rights -- and prevent states from passing new ones. And while Bush has not yet come out in favor of the amendment, he did throw a bone to the churches who began promoting it on Oct. 12 -- one day after National Coming Out Day -- by officially proclaiming last week to be "Marriage Protection Week" nationwide. Though same-sex marriage may not be the defining issue in the 2004 presidential race, some experts believe it will be a key issue in small towns and conservative states nationwide.

Auburn may be only a three-hour drive from San Francisco, but in many ways it is closer to the heartland towns of the Midwest. This is a deeply Christian town -- there are five churches within walking distance of the Adamses' home alone -- and the ratio of homes to pickup trucks to American flags on their block is 20 to 18 to 7. Auburn is so all-American that it has occasionally become the Hollywood stereotype: For the small-town scenes in "Phenomenon," the 1996 movie about overcoming intolerance, Auburn was the backdrop. Now that the population is growing with refugees from the big cities, many native residents resent the less traditional ideas they bring with them.

It was into this climate of flux and conflict that Jean and Toby arrived a year ago, and they didn't know what to expect. Toby was hopeful that by being there in a "not too pushy, not too political way," people would come to like and accept them for who they are, and so far, she's seen no overt reason to think the neighborhood doesn't. Nonetheless, Jean still has doubts about an incident that occurred soon after they arrived: In two weeks, she had four flats. "Right after I got out here, I had to replace two of the tires on my truck," she says. "At first I thought someone had stuck nails in them on purpose." These days, Toby and Jean try not to be any more obvious about their relationship than any other couple on the block, though Toby occasionally gets frustrated by the implicit decision they've made to not get in people's faces with their relationship. "We moved here so we could just mow the lawn and then sip some lemonade like the rest of small-town America, but one morning some Jehovah's Witnesses showed up at our door with a pamphlet about 'building stronger marriages,'" she says. "And as they walked away, I told them that if they wanted to help our marriage, they should vote for same-sex marriage rights, but when I tried to follow them to make sure they'd heard me, Jean shushed me and said she didn't want to get political, she just wanted to get to the farmers' market." While no longer openly suspicious, Jean remains more shy and guarded than Toby, for good reason: She has seen this kind of town from the other side.

The last time Jean lived in a small town, she was still in the closet, and this has made her wary of Auburn. As a little girl, Jean was raised in the town of Boulder Creek, Calif., population 7,000. There she was brought up to be a Christian like her parents and as feminine as possible. "Growing up in a small town, I was really judgmental about myself," she says. "When I was a kid, I was a tomboy, but when puberty set in ... I just sort of dressed and acted the way I thought people wanted me to dress and act -- stereotypical girly-girl. I had long, dyed-blond hair. I wore a lot of makeup." Raised by a stepfather who was deeply homophobic and a mother who tolerated his views, "I internalized homophobia to the max." It wasn't until she was engaged to a man -- her high school sweetheart -- that she began admitting to herself that she'd had same-sex feelings and attractions since she was 12. "It took me six months after that to work up the courage to go to a bisexual support group," she said. The group, half an hour's drive from San Jose, is where she met Toby. Soon after joining the group, Jean cut off the engagement, along with all her hair, and came out to her family as a bisexual. She became a pagan and an activist, trying to help parents whose children had recently come out understand what it meant. Her self-described "dyke" appearance evolved gradually, but today she is protective of her look. "Even if I stand out in Auburn," she says, "I can't go back to the Stepford look. That's not who I am anymore."

For Toby, the route to bisexuality was less circuitous. "I never had a coming-out process," she says, "because I was never in. I had my first crushes on a girl and a boy when I was 10, and most of my life I didn't have a word for it." She acknowledges that in Auburn, she gets fewer stares than Jean. Generally speaking, with her dark blond hair usually pulled back in a ponytail and her practical khakis and stain-resistant T-shirts, she looks exactly like the suburban mom she is. Raised by a liberal, atheist family in East Coast cities, her larger revelation was a faith in God. "'Godspell' and 'Jesus Christ Superstar' are how I got religion," she says. She started going to church in college, decided she liked the Episcopal Church because it was "more stained glass and incense with less of the bullshit" of Catholicism, and has been going ever since.

For five years they lived separately in the suburbs of Silicon Valley, not far from San Jose. In 1999, Toby decided to have a baby with the help of a close friend who agreed to act as her sperm donor. Toby and Jean, who had had an on-again, off-again relationship, were just friends at the time. But in the fourth month of Toby's pregnancy, something changed: "I got food poisoning while I was pregnant, and she [Jean] took me to the hospital, and I knew that things that hurt that bad hurt less when she was holding my hand ... I told Jean, 'Listen, I don't know if this will work out forever as I hope it will, but I want you to be my Lamaze partner, I want you to be there for the birth.'" In September 2000, Kalen was born. The women moved in together the next year. But although Toby considers Jean to be Kalen's "dad," legally Jean has no rights as Kalen's parent.

"People tend to think legalizing same-sex marriage is an abstract issue, but it's not," says Toby. "If we were allowed to legally get married, it would put a whole different spin on everything -- on finances, on parenting, on how she's treated as the dad. When you're married as a heterosexual couple, a lot of things just click into place, but we just finished the wedding and now we have to spend thousands of dollars to draw up contracts to get what we would normally get. For example, I have to pay taxes on her health insurance benefits as though it were income. The guy who sits next to me, his wife gets health insurance, he doesn't pay taxes on it." Even more important, the sperm donor is still considered Kalen's father at the moment, although California law allows Jean to adopt Kalen under 'stepparent adoption.' And though one of Gray Davis' last acts as governor of California was to sign into law a bill granting many more rights to same-sex couples, it won't take effect until 2005. In the meantime, if something happens to Toby before the adoption goes through, "it's a crapshoot in the family courts," she says.

Paradoxically, the biggest obstacle to legalizing same-sex marriage, say Toby and Jean, is put up by advocates who frame it as a gay-rights issue -- because that turns it into a fight between the Christian right and gay-rights promoters, rather than an issue of sexual equality. "It's not a gay issue," Toby insists. "We're not gay! We're bisexual." She explains the legal-marriage difference through a puzzle of four couples. "Let's say my friends Bryan and Kathleen are bisexual, my friends Thomas and Mary are bisexual, my friends Chris and Ted are bisexual, we're bisexual." she says. "Chris and Ted get married, they get no rights, Jean and I get married, we get no rights. Thomas and Mary get married, they get all the rights; Bryan and Kathleen get married, they get all the rights. But we're all queer, we're all equally as queer! It's a plain and simple issue of human rights."

Legal rights aside, soon after moving to Auburn in 2002, Toby asked Jean to marry her -- and slipped an engagement ring on her finger when she said yes.

That's when the trouble with the Episcopal Church began. As an Episcopalian, Toby wanted a religious ceremony to mark the occasion, but while some Episcopal churches are currently providing ceremonies to bless same-sex unions, St. Luke's is not one of them. Nor would the Episcopal priest recommended by a friend proceed in the end, bailing on them three weeks before the wedding over the pronoun changes -- too many wives -- in the vows. Finally, an ordained friend of a friend agreed to perform the service. On a sunny afternoon in July, on a Santa Cruz bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, they said their vows under the shade of redwoods. Kalen, then 2-and-a-half, was the flower girl and threw rose petals happily into the wind. The service the officiant performed was mainly Episcopalian, but the brides also wore matching patterned belts of a pagan ritual, and instead of veils, both had wreaths of blue and white flowers in their hair. In photographs, they are beaming at each other, Toby in a white dress, Jean in a dress of midnight blue. And although the celebrant who officiated signed a domestic partnership certificate rather than a marriage license, in their hearts Toby and Jean -- who now share Toby's last name -- consider themselves married for life.

The street Toby and Jean live on is lined with split-level houses painted in tasteful colors, beige or yellow or gray, each with a postage-stamp yard. Every house is a variation on a theme: if not a pickup truck in the driveway, then an SUV; if not a tricycle, then a basketball hoop. The lawns are sprinkler-fed green and neatly trimmed; the flower borders teem with zinnias, crepe myrtle, roses. People take pride in their yards, and in orderliness. Almost every other house flies an American flag, though Toby and Jean do not. Next to their house, at the crossroads of two streets, stands a sign: "Warning: Neighborhood watch. We will report all suspicious activities and people to the police." Although usually less politically showy, today Toby is feeling defiant. "I've been meaning to get a bisexual flag," she says, "but I just haven't found the right one."

In fact, there is little visible about Toby and Jean's house to set it apart. If you ignore the rainbow flag and pro-Green bumper stickers on the pickup truck in the driveway, this could be the house of any neighborhood family with a 3-year-old. In the living room, crayoned butterflies are taped to the wall at preschool height; on the dining room table a lone Cheerio lies marooned 4 feet from the high chair from whence it came. This particular Sunday afternoon, Jean is in the kitchen stirring tomato sauce as Kalen runs into her leg, yelling. "Look, Boo, look!" she says, holding up a drawing. "That's great, Kalen. Go show Mommy." "Mommy, Mommy!" Kalen runs off yelling to the home office at the other end of the house. "Boo is her name for me," explains Jean, looking up from the stove. "When she was really little she would kind of coo at me, and I'd say, 'Look, Toby, she called me 'Boo'! So that's who I am. I'm the dad."

But thus far, people in Auburn are not quite ready for a woman to be a dad, no matter what name you give her.

Doug and Debra Kyles live a few houses down the street, with three young kids of their own. They've gotten to know Toby and Jean, and sometimes Debra baby-sits for Kalen. Clearly she has real affection for the little girl, but when asked, she expresses frank concern for Kalen's future as the daughter of a same-sex couple. "They're nice people," she says, "and if they needed me for anything, I'd be there. But I do have an opinion when it comes to having a child in that environment. I don't think it's right. I think a child needs both male and female role models, to balance the child out. Bottom line, I just don't agree with homosexuals raising children."

Her husband, Doug, a middle-aged welding contractor who has lived in Auburn all his life, goes further. "I don't care if they're really nice," he says. "If I had it my way I'd oust them. I just don't like them around here. You think I want my kids looking at that? And thinking hey, that's OK? There's a lot of rednecks around here and they're not going to tolerate it, trust me." The Kyles are planning to move as a result of Toby and Jean's presence. As of yet, though, there's no For Sale sign in front of their house.

The preschool Kalen attends shares space with the county fairgrounds, and though it is within walking distance from Toby and Jean's house, Toby is running late the Monday of the orientation for new parents and decides to drive. She wears a T-shirt and shorts to the meeting, her hair pulled back in a short ponytail, and as she pulls onto the dirt driveway and rolls down the window to talk to two parents on their way into the building, she looks every bit like a slightly harried soccer mom. "Do you know which room we're supposed to meet in?" she asks. The woman answers, then squints. "Hey, you were at St. Luke's a few weeks ago and stood up to give thanks, right?" Toby says yes. "Ah," says the woman, and pauses. "Well, see you inside."

Past the school sign painted in rainbow colors there is a noisy, hot room crowded with parents and their waist-high children. The parents here for the meeting are mostly women, mostly in dresses and makeup. The women have all taken care with their hair, and they are all traditionally feminine looking, and white. When Jean arrives, she stands out: no makeup, boy-cut blond hair, black jeans and an oversize, navy collared shirt. "This is my wife," Toby tells one woman nearby.

The meeting is long and boring. The wives are friendly to Toby and Jean. But when one of them is asked later what she thinks of the couple, she gets defensive: "Oh, them? Oh, you want to know what we think, up here in the middle of nowhere?" After softening, she acknowledges that they don't blend in. "Well, up here you just don't see it that much, so it tends to really stand out, though I really don't care. What the parents do is their own choice, as long as the kid is raised OK. But I lived in the Bay Area for a while, so maybe I'm more accepting than some."

As far as Kalen's teacher, Natalie Piercy, knows, all the preschool parents are very accepting of the Adams family. "People really love Kalen," she says. "But recently there've been a lot of new hires and they're always kind of surprised by Toby and Jean. They're shy to the idea, and then they see how it is and it's OK. Personally, I don't see any problem, with their situation or with Kalen's situation, but to be honest I do wonder how it will affect her in elementary school. Kids can be mean."

Born and raised in Auburn, Piercy, 23, says there's an ambivalence here about same-sex marriage -- one that she still struggles with herself. "My parents are really conservative and they've had a huge impact on my views," she says. Growing up, "the closest I came to knowing a gay person was watching "The Real World" -- which I think has had a huge impact on my generation as far as that's concerned. They introduced gay couples to the world." Today in Auburn, she says, "people like Toby and Jean, but when you ask them if they support gay marriages, they say no. That is in me too a little bit, and I don't really know how to address or confront that."

Three weeks after announcing their marriage in St. Luke's, Jean and Toby are back at church again -- and this time it is Toby who is nervous. In news that made headlines across the country, the Episcopal national convention recently decided to approve an openly gay bishop and voted to recognize that some dioceses hold blessing ceremonies for same-sex couples. Those votes have split the St. Luke's congregation. "This is a challenging time for a lot of really solid churchgoing Christians," says Father Marcia, "and I'm aware of that on a very definite level." At St. Luke's, some parishioners are angry that their bishop voted to approve the ruling, and though Father Marcia agrees with the bishop's decisions, she has called a meeting of the congregation after the Sunday service to talk about it. One of the issues to be discussed is Toby. Currently, St. Luke's parish does not have a sacrament blessing same-sex marriage -- and although Toby accepts and does not expect that to change with the recent ruling, many in the parish don't know that. A change would be disastrous, says church member Annie Holmes, one of the few Democrats in the parish. "If the new pastor wants to institute some kind of sacrament," she says, "that will really drive people into the arms of a more conservative church." Financially, St. Luke's can't afford to lose a single member.

The meeting is held after service in the ugly, grayish community room. Father Marcia's white collar peeks out from under her flowered dress as she sweeps past the rickety folding chairs and round tables filled with people. Bill Gausewitz, the senior warden and meeting officiant, stands. "I want to explain what the rulings actually were," he says. "They confirmed an openly homosexual bishop. They authorized local dioceses to establish rites of blessing gay marriages, and recognized that parishes are dealing with this in their own ways." He clears his throat. "I want St. Luke's to be open and welcoming to anyone who wants to come here ... Some people say they don't want to keep going to this church if the convention is going to ... I say that the convention doesn't change anything for our diocese." A few people glance surreptitiously at Toby, who looks only at the warden.

"Besides, there was a time when Father Marcia wouldn't be here," Gausewitz says. "Somehow that's worked." The room erupts in laughter and the tension eases -- for all except one older woman, who is visibly shaking with anger as she stands up. "There's no comparison," she says, "between the ordaining of a moral woman and a twice-divorced man who's been living with another man. We've got to protest. I remember Germany in the '30s and nobody protested and you know what we got from that."

One gray-haired woman in a gray dress seated across from her, obviously a friend, cuts her off. "No, things change and we learn," she says quietly and serenely. "This too will become normal," she says. "Just like everything else."

There is silence, and finally an older man breaks it. "Whether or not I agree with what [the national convention] did," he said, "the main thing I'm concerned about is our parish. If we can hold together, that's what I want."

There is a chorus of voices around the room: "That's what I want." "I want that too." Some people are teary as the murmurs of agreement go on.

Finally, Toby speaks. "A few weeks ago I thought I wasn't accepted here. I thought, 'Take this cup away from me.' But if I leave, where will I go? So I'm going to stay, and I hope people who feel completely differently will also stay."

And in closing the prayer circle, the same woman who had stood up shaking in anger held Toby's hand. "We're a close parish. We'll get through this somehow," she said.

Overall, Annie Holmes was proud of how tolerant her fellow church members were. "There are a lot of people who really feel that same-sex unions are immoral," she says, "but I think people are really trying not to criticize them. We all know Toby, Toby is very devout and we all like her. That makes a difference! You can rail against people in the abstract, but when you know them it's a little harder."

Twenty minutes later, Toby, Jean and Kalen have their family photo taken for the church directory. They are parked next to the woman who railed against Nazis and held Toby's hand, though they do not know it. "Hi," they say to her as they wrestle Kalen into the car. Before leaving, I stop the older woman. "What do I think about gay marriage?" she asks. "I don't agree with it, but we're a strong parish. We'll get through this somehow." Though I don't realize it at the time, she thinks I'm stalking her by asking this. Four days later, she has a minor heart attack -- and blames it on the stress of talking to a stranger about such a volatile subject. Such are the tensions that come with this issue in Auburn.

It is not overly dramatic to believe that, in moving to a small town in the American heartland, Toby and Jean Adams have committed a revolutionary act. Nor is it wrong to say that many Auburn residents -- their neighbors, or the members or St. Luke's church -- are revolutionaries too, in their own way. Despite the everyday tensions and uncertainties, they are living together in a way that few would have thought possible even a decade ago.

Not far from Auburn, in the little town of Cool, Calif., real estate agent Brent Stone says acceptance is growing. Although Cool is smaller than Auburn, Stone and his male partner of 13 years say they've had no problems being accepted in the three years they've lived there. They have two adopted children of mixed race -- one in first grade, the other in the fourth -- and "they are almost treated like celebrities here," says Stone. Whether or not he speaks with a tinge of hyperbole, as might be expected of a real estate agent, Stone actively encourages same-sex couples to move to the area -- and, apparently, they are.

And yet the awkwardness and tension are real, and in the current climate, Toby and Jean are not sure they're going to stay. Recently, says Toby, "I found myself having to have my first conversation with Kalen about how people might not be OK with her family, and that's a lot to lay on a 3-year-old. But I don't want Kalen to ever think something is wrong with her, and clearly the time is coming soon when someone will say something to her."

For every Doug Kyles in Auburn there is a Father Marcia, but for the majority of individuals, the fault lines run straight through the heart: While they like and accept Toby and Jean, they still think same-sex marriage is wrong. They are at a crossroads -- in one direction an amendment outlawing same-sex marriage, in the other, the legalization of it. They may oppose it in abstract principle, but when they meet Toby and Jean and Kalen, there's a native impulse to see that they're just nice people. The same ambivalence plays out in small towns and cities elsewhere in the American heartland.

According to Scott Keeter, author of "The Diminishing Divide: Religion's Changing Role in American Politics," an amendment banning same-sex marriage is unlikely to pass, given the lack of national support and the more immediate concerns in Congress over the Iraq war. Nonetheless, he says, "there will be plenty of people who try to make this a wedge issue in the 2004 presidential election. And among conservative white Protestants, Bush enjoys almost unanimous support, so he has a fine line to walk" if he wants to also gain the moderate votes he needs to win. In contrast, Howard Dean has promised that if elected president he will do for the nation what he did for Vermont as governor: legalize civil unions. With a recent Gallup Poll showing the nation split almost in half in favor of allowing gay unions at all, the issue has the potential to force a decision from heartland voters who are not yet ready for for either an amendment or legalization.

As more and more couples move into small towns, slowly, haltingly, they are gaining acceptance. Like other social movements, time helps. And 10 years from now, maybe Kalen won't have to explain her dad. "It's wonderful living in California with all the extra rights of domestic partnership. It's just as wonderful as sending black kids to their own school during segregation -- separate but equal, isn't it great they get to go to school at all?" says Toby, her voice dripping with sarcasm. "Everybody knew that wasn't right and eventually they had to change it. And they're going to have to change this too."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

We want to make you a part of this series. What is the state of your union? Did you find the one and never look back, or has finding lasting love been a marathon of trial and error? Did you have a fairy-tale wedding only to watch things crumble once the reception was over, or have you glided along in marital bliss since Day One? We want to hear your stories of joy, romance, heartbreak and pain. After all, partnership, as we all know, is a complex concoction of all of those things. (Please remember: Any writing submitted becomes the property of Salon if we publish it. We reserve the right to edit submissions and cannot reply to every writer. Interested contributors should send their stories to marriage@salon.com.)

Shares