If you're looking for proof that the kids are not all right, take a short stroll down Haight Street, San Francisco's famed relic of the free-love era. In just the four blocks between the mouth of Golden Gate Park and Booksmith, the neighborhood's oldest bookstore, you'll pass at least 10 kids offering you drugs. Usually they mumble "greenbud, greenbud, greenbud" under their breath as they pass, gesturing with their eyes toward the side street they'd like you to follow them down to make the transaction. The kids are white, black, Asian, Latino, pierced, tattooed. Some have yellow teeth, sores on their faces, visible track marks on their arms. Others look healthy and glossy, though hardly sober, in expensive sneakers and trendy skater T-shirts, rich kids stomping the streets, earning a little extra cash -- or maybe looking to spend some.

And if you're looking for more proof that the kids are not all right, pick up a copy of Meredith Maran's "Dirty: A Search for Answers Inside America's Teenage Drug Epidemic." Maran, a Bay Area journalist and mother of two, opens with some daunting statistics about our country's adolescents:

Why do American teenagers abuse drugs with such alarming frequency? And what can we, as a society, do about it?

Maran wisely seeks to answer those questions not through more applications of statistics or polemics but by getting to know three very different teenagers: Tristan, an angel-faced boy from wealthy Marin county with a fondness for folk music, Earth Day and any drug he can get his hands on; Zalika, a black middle-class sometime prostitute who says, "I'm not addicted to drugs, I'm addicted to men and drama"; and Mike, a white working-class methamphetamine addict who has spent the past few years caught in the cycle of California's justice system. By choosing kids from such different worlds, Maran manages to present several facets of the nation's losing war on drugs: from the schools to the streets to the treatment centers, to the local juvenile halls.

What's most refreshing about "Dirty" is Maran's lack of objectivity. She follows all three kids -- their families, and their addictions, and the underpaid and often heroic professionals who work to help them -- with the watchful eye of a worried mother. She writes honestly about the anxiety she feels when she doesn't hear from the kids -- and her inability to always maintain a healthy distance from her subjects and their pain. It is this "frazziness" that makes the book so compelling -- throughout her late-night conversations with these self-destructive but incredibly likable teenagers, she makes the reader feel as helpless as she does. We can't stop Zalika from going back to her pimp. We can't persuade Tristan to stop moving from pills to E to pot to cocaine in search of the "ultimate high." And though we might want to, desperately, we can't believe Mike when he promises Maran that he can get clean by himself.

Maran's tendency toward frazziness is also apparent when she reflects on the troubles she had with her own son, Jesse, who as an angry teenager in Oakland did drugs, got kicked out of school, stole cars, got arrested, and was beaten up by cops. Jesse has since gotten his life together and is now a 23-year-old practicing Baptist minister attending college. He has spent several years counseling troubled teens at a local treatment center. On this night he is joining his mother at a reading at Booksmith, where all the proceeds of the book's sales will go to the Haight Street Free Clinics. Maran has agreed to bring her son to meet with me before the meeting. It was not the first time, she said, laughing, that a reporter wanted to see the two of them together.

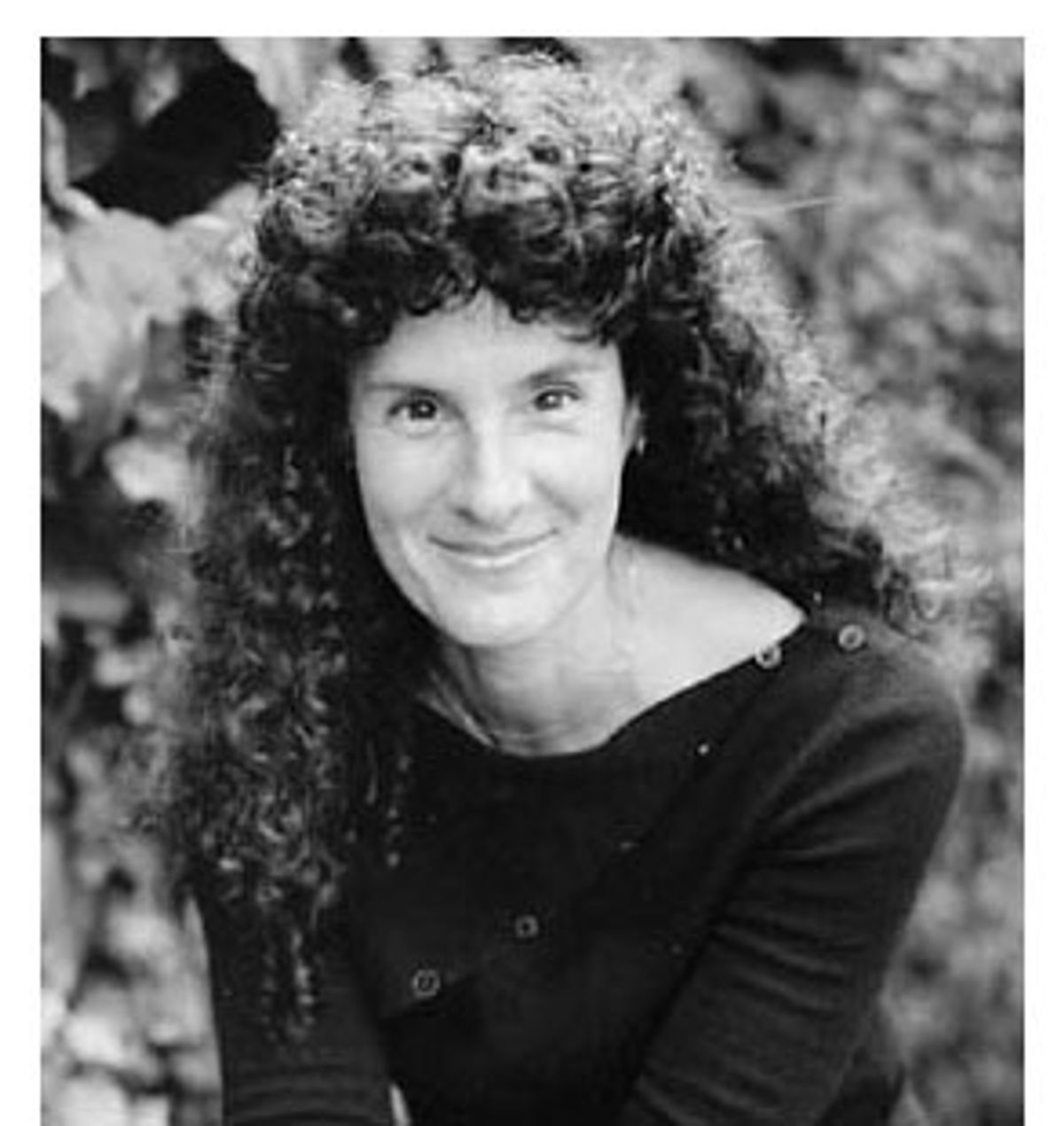

We take our seats at a pizza place across the street from Booksmith. Over Maran's head and out the window, I can see kids selling drugs on the street. Maran, 52, looks at least 10 years younger, with long, curly black hair and bright dark eyes. Tonight she is decked out in Berkeley chic -- which is to say, not chic at all -- with a black zippered sweater, black slacks and comfortable shoes. She greets me warmly, but her son is more guarded. Tall and handsome, with full cheeks, wearing baggy jeans and scuffed sneakers, he extends his hand for me to shake but lets it fall away quickly and doesn't make eye contact as he mumbles a "how you doin'," which sounds more much b-boy than Baptist.

Maran begins by giving me a quick update on Zalika, Mike and Tristan. Zalika lives with a new pimp now. Mike is still evading warrants and on the run, calling in sporadically to let people know he's OK. Of the three, Tristan is the only one Maran isn't too worried about. "He has options," she says, "and you get the sense that he's just experimenting rather than getting lost."

I ask her to expand on one of the book's main points, that too much of the national discussion on teenage drug use focuses on blaming parents.

Maran laughs nervously, her teeth whiter than the napkins on the table. "Especially don't blame me. Absolve me first, and then we'll work on the rest of the country!"

"But Mike's got an alcoholic, permissive and inconsistent father who hits him," I say. "Zalika's father has hit her too, and cheated on her mother, and she knew it. And Tristan -- his father is also a drunk -- how can you not blame parents like this?"

Maran nods her head. Jesse, seated to her right and across from me, studies the menu. "Parents make terrible mistakes," she says. "I know I did, and I still do every day. That is absolutely a fact of life. Parents fuck up. But you know -- we can't answer the question of why kids fall into these traps. What we do know is that there are some things that make the problem better, and some things that make the problem worse. But can't we please, please just do everything we can to make it better first? And then we can worry about whose 'fault' it is."

Jesse orders us a large sausage pizza, and then tells me why he started getting in trouble. "For me, the problem wasn't about drugs. I mean it was drugs, but it wasn't the core, it wasn't the cause ... I had a lot of personal anger to work through, anger towards my mom, towards my dad. And plus I was crying out for attention: I wasn't lower class, or a member of a minority group, or on welfare or Section 8, but I thought, you know, just because I don't look bad on paper, doesn't mean I'm not still hurting. I wanted the world to know that this middle-class white woman -- my mother -- did hurt me."

His mother does not bat an eyelash, just folds her hands, as her son speaks his indictment. Still, I'm not about to ask for more details. They're all in her 1996 memoir, "What It's Like to Live Now," in which Maran, a self-avowed child of the '60s, described experimenting with just about every drug, spirituality and lifestyle known to man, frequently on her young son's emotional dime. Still, she also gave him life, raised him, pleaded for him in court, waited by his bed in hospitals, waited for his phone calls in the middle of the night -- all the things mothers do for their children.

I don't push him. Instead, I turn to his mother. She has been defending the parents, her son is blaming them, and I'm about to point out the contradiction between his view and hers, when she holds up her hand:

"Wait, before we do this. Can I just stop you for a second? I know that right now I'm on a book tour, and talking about this seven times a day to complete strangers, some of them face to face, and some of them I'll never see -- and it's easy to turn my story, Jesse's story, the stories of the kids in the book into... a sound bite."

She's still smiling, but with a warning flash in her dark eyes. "And I know you aren't a mother, but even so, maybe you can understand how it feels to be told every single day -- by caseworkers, by judges, by psychiatrists, by your own children -- that you're a bad mom, when being a mom is the most important thing to you in your life.

"I thought it might be my fault, all of Jesse's problems, everything." She takes a deep breath and continues. "And you know, one of Jesse's probation officers suggested that it was because I was gay that he was having trouble. The feeling that you have screwed somebody up, you have no idea what that's like. Think about Barbara, Mike's mom, who has had the courage to come with me on tour, who is going to be there when I read tonight, and her son Mike is on the run right now. It's hard enough for me to do this, and look what I have to show for it--"

She gestures proudly toward Jesse, who neither nods nor blinks, just sits patiently, waiting his turn to speak.

"Barbara can't point to her son now, safe and sound: She doesn't know where he is. Do you understand that?"

I don't understand it, not really, even though I've spent eight years working as essentially a back-seat parent: first at a wilderness treatment center, then in job-training facilities, and finally in juvenile hall. I've had hints of that late-night panic, when kids ran way, when they failed to meet me for job interviews or never showed up in court. And I've been to funerals -- but of course they were never my own children. As for shame, well, in society's eyes, I got automatic sainthood just for being there at all -- because I was filling in for the no-good parents.

"The other night at a reading, two women were crying," Maran says. "And one woman raised her hand and said, 'My son is in juvenile hall.' Me, I would have been too ashamed to stand in public and say those words. But you know, I've been doing interviews with all these major personalities, and every single person has a story to tell me the minute we are off the air, or off the record. You can be the most educated, affluent, caring, attentive parent in the world, and still your kids aren't safe."

She shakes her head.

"I'm just trying to stay human in the process I'm in right now, telling all these stories, over and over again, these powerful moments of my life, the lives of people I write about. I've started getting frazzy again ... Right, Jesse? I've been frazzy."

"Yeah." Jesse nods, and of course Jesse should know. His is the story she is having to tell, over and over again. And he is the one who has been on both sides of drug addiction. Why did he start, and why did he stop? What can he teach us?

The moment I ask what stopped him, I wish I hadn't. Jesse starts off by telling me that "God's divine target" was on his head, and he weaves together a story of cliffs, visions, dreams and near-death car accidents straight out of a revival house testimonial. His soliloquy culminates in a moment at a local Baptist church, where, he says, "I felt God reach out to me, and I sat down and I started crying."

Christ, I think, the kid is a Jesus freak.

"I felt like God was telling me I needed to make a decision right there to accept him," Jesse says. "I just made the decision right then and there to accept Christ as my savior. And that was a turning point for me."

He chokes up and his voice breaks. His mother reaches out her hand and rubs his neck.

"It wasn't a philosophical understanding that I came to. It wasn't an intellectual set of beliefs that I agreed to. It was an experience. As much as I resisted him for years, he dealt with me, and no matter what I had done, I could never stop him from loving me ... It's so hard for humans to see somebody who stinks, to smell the stench, and still love the person, but that's the way God loves, that's how he has dealt with me."

Jesse wipes his eyes and shakes his head with an embarrassed laugh. "That's, uh, how I changed, in answer to your question."

"So you found grace?" I offer.

"Well, yeah," Jesse says, nodding. "Or grace found me, because I didn't really know what I was searching for."

Jesse continues in this vein, explaining how God chose him, how God is infinite, and I sit, stunned, and watch my pizza get cold. This "Jesus freak" did give us an answer, even if it wasn't the one we wanted to hear. At the end of "Dirty," his mother has made a list of things we can do as a nation to help kids. She talks about "supporting good parenting" -- not just parenting by mothers and fathers, but also by the village. She talks about the need for smaller classes and more treatment centers. She suggests a move away from the Narcotics Anonymous model and toward treatments that play on kids' individual needs and strengths. She says the juvenile justice system needs to be revamped. Reasonable suggestions all, if almost impossible to see realized.

Nowhere on her exhaustive list, however, does this mother of a son who was clearly saved by Jesus once mention religion as a potential cure for what ails American youth. Even though it was the difference for her own son.

I turn to Maran and ask her why. She seems as stumped as I am. "I'm listening to Jesse, and I'm realizing that this is sort of what Tristan said when he went to Earth Day and he felt all these people singing about love together. Tristan doesn't believe in God per se, but he said that 'all the evil left him.' That's how he described his turnaround. And he's the one who now seems to be doing the best of all the kids."

The time has come to pay the bill. Maran heads to wash up, and Jesse and I keep talking about the relationship between his faith and his work with young people.

When Maran returns, she is still thinking about religion and its absence in her book. "What do you write?" she asks. "Give kids spirituality, bring kids to temple, bring them to church, bring them to the mosque? That's not something I can prescribe. But I do talk about this: We need to be helping a kid find what's in him or her that is good before, during and after they get into trouble.

"Do you know how many people have asked me, in the past five years, as a Jewish, lesbian, agnostic, wannabe Buddhist, 'What do you think about your son being a practicing Baptist minister?' And I try to keep it real -- it's really brought me up against how much I want my kids to be just like me, and how validating it is of me when they act like me or have my values. And it's been a struggle for me to learn how to accept -- not just accept but celebrate -- what gives Jesse joy: his spirituality, which flies in the face of pretty much every thing I believe in."

She reaches for her bag. "Throughout the book, I'm trying to say, pay attention to who your child is. So spirituality, or religion -- you're right." She shakes her head. "It's not on the list. It's not on the list, but I hope it's in the book."

We head out to cross the street, past the tattooed teenagers, where a small crowd has already begun to gather on the sidewalk in front of Booksmith, waiting for answers.

Shares