Each year, a growing number of Americans agrees to be locked behind bars.

They check in at manned guardhouses, waiting to be sealed inside their gated communities, where they obey countless rules written into their deeds. They grow only approved flowers and walk dogs no taller than 16 inches. They choose window treatments with trepidation, afraid a peeping neighbor might report a deviant swag to their homeowner's association -- which can and will foreclose on rebels. They endure these indignities for one reason: order. "In the end, it's not about security at all," says Mary Gail Snyder, a professor of urban studies at the University of New Orleans and co-author of "Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States." "Most gated communities are incredibly easy to break into. The appeal is really about control."

But more than just a way to escape the chaos of real life, these enclaves are also becoming ghettos, increasingly targeted to specific groups. Golf addicts lock themselves away in sand-trapped communities such as Colorado's Fox Acres. Sections of the Los Angeles suburb Monterey Park are specially feng-shui'd to serve the Asian population.

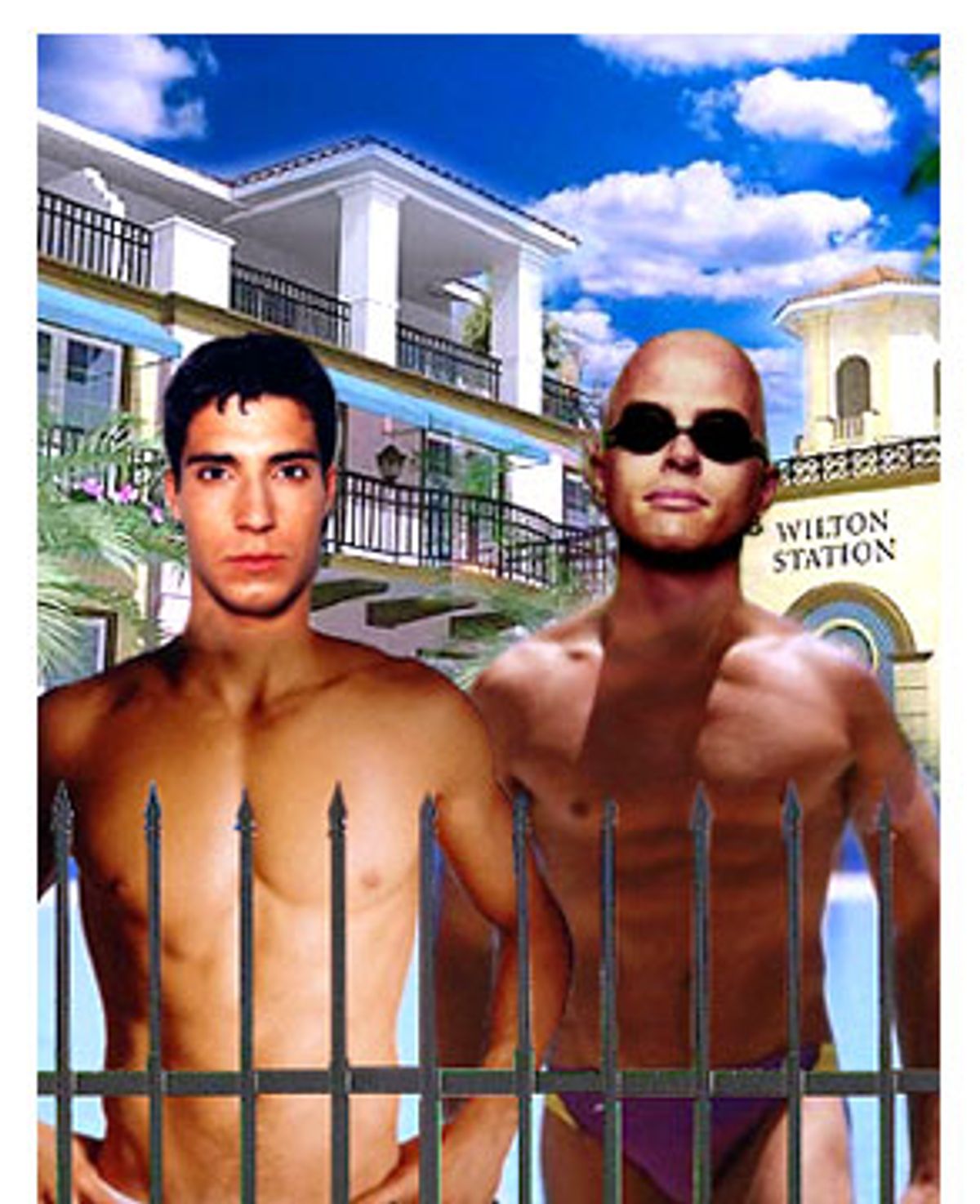

But the newest example will likely be the most controversial: Wilton Station, the first gated community in America to specifically, if not solely, target the gay market.

Now under construction in Wilton Manors, Fla., a bedroom suburb of Fort Lauderdale, Wilton Station will be an ambitious low-rise project of 272 varied condominium units: brownstones in dignified rows, loft spaces to tempt the trendy, and quaint porches to add a Mayberry touch. The prices, from $300,000 to $500,000, are less quaint. On-site retail spaces will let young professionals dry-clean John Varvatos sweaters or stumble out of a martini bar without leaving the complex. A vast health club will overlook a 72-foot lap pool, "beach" area, waterfalls, two spas, and a "Tiki Hut." Other perks: a private screening theater, pet areas, and the conspicuous guardhouse, where security guards will let the privileged through that magic ingredient -- the gates.

Its developers are calling it an upscale "village," implying traditional values. Its detractors are calling it a yuppie suburban version of a gay ghetto -- or, worse, a Mecca for sinners who'll need saving. And it's all happening at a time when gays are sparking widespread anger by attempting to "appropriate" the tradition of marriage, and President Bush is seeking to institutionalize homophobia with an anti-gay-marriage amendment to the Constitution.

Is this the new gay American dream: First you get illegally married, then you move to Wilton Station?

The $100 million project's development team, all friendly, middle-aged straight men, see it as anything but a political statement. "To me, it's not a controversial issue," says Jim Ellis, chairman of Wilton Station LLC. "I want to build a really good product and it needs to sell. If people don't like it, they won't buy. Simple as that."

Well, not really. Wilton Station, which will welcome its first residents in fall 2005, raises other questions: Will rabid conservatives protest it as an attempt to "appropriate" the "traditional" suburb? And, if it succeeds, will it trigger even more splinter-group enclaves?

At the moment, Wilton Station is nothing but a big empty hole: Twelve acres, formerly the site of a beer distributor's warehouse, bordered by an (occasionally cacophonous) railroad, and a 300-foot stretch of the lushly overgrown canals that cordon off the town of Wilton Manors (pop. 13,000), and give it its nickname, "the Island City."

The hole sits next to the local Kiwanis Club, which recently hosted a chili cook-off to raise money for needy children, and the First Christian Church, which runs a preschool. Nearby is the traditional center of Wilton Station, an intersection known as Five Points, where in the '50s, two castle-like towers stood. In one, a woman operated a bird store; her parakeets and canaries flew about constrained inside the stone walls. A never-sold mynah bird was famous for its biting remarks.

Back then Wilton Manors was a typical town, full of modest bungalows and banal intrigues. By the '80s, however, Wilton Manors had rotted into a mildly crime-ridden place, and gay escapees from Fort Lauderdale moved in to snap up cheap houses and gentrify the hell out of them. That initial trickle became an influx, and today an estimated 35 to 40 percent of the residents are gay or lesbian. It is the only American city, other than West Hollywood, Calif., where a majority of City Council members are openly gay.

Statistics reinforce the picture: In the 2000 census, the city of Wilton Manors had the highest percentage of households reporting as "unmarried partners" in the entire U.S. Only 37 percent of households are "married," well below the national average of 59 percent. The number of households that include children is 20 percent below the national average.

According to locals, Wilton Manors is a place where gays and straights coexist peacefully in a sort of mini-Epcot of sexuality. "People have just realized that sexual preference isn't that important," says Rex Gillenwater, 48, the (straight) president of the Kiwanis Club, which counts the former mayor among "quite a few" gay members. "What matters is the kind of person someone is. Anyone who had a problem with it has moved away."

Don Ice, an openly gay man who owns a pet-sitting business, finds the town hostility-free: "You have your little gay realtors, your little gay shops, your fancy hamburger place." His only real complaint: He has to drive across the waterway to Fort Lauderdale to find a decent leather bar.

"It's a great little place," says Donna DeGroot, a retired Catholic schoolteacher, who has lived in Wilton Manors since 1989 with her husband, John, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former journalist. "And the gay population has made it an even nicer place to live." The DeGroots' home has tripled in value thanks to gay renewal, but their ties to the town are more than financial; they have a gay neighbor they love as a brother.

"Intolerance," says John, "is not tolerated here."

Or at least it's a very minor factor, says Andy Weiser, a local gay realtor. "There is a redneck population in Wilton Manors," he admits. "But this is still, by far, the most liberal part of South Florida." The town even has its own police force, reputedly more gay-friendly than the local Broward County Sheriff's Office.

Given the town's placid gayness, and its explosive real-estate market, it's not surprising that Jim Ellis and partners decided to build Wilton Station and market it so ambitiously. The first wave of national ads, eliciting requests for more information, debuted earlier this year in both gay magazines (the Advocate, Out) and mainstream titles (the New York Times Magazine). Buoyant same-sex couples -- as well as hetero duos, and a woman clearly doomed to live alone with her dog -- populated the campaign. Words like "open-minded" suggested gay-friendliness; the ads in the Advocate and Out went further, highlighting reception areas perfect for "commitment ceremonies."

Though Ellis stresses that they are targeting both gays and straights and have a strict nondiscrimination policy, he expects the majority of buyers will be gay. "I could see it going as high as 60 percent," he says.

Accordingly, the developers decided to find out "what amenities would be of particular interest to the gay and lesbian community," as John Patrick, the chief marketer, told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel this March. They set up focus groups, inviting up to 20 young professionals, both gay and straight, to weigh in on everything from lifestyle priorities to the nuances of moldings.

What did they learn? "These people care greatly about their bodies," says the project's architect Vernon Pierce, a straight man who grew up with a gay sister. "The health club was viewed as extremely important, so we designed a facility that will be second to none."

"Another key area of concern was entertaining," says Pierce. "So we upgraded the kitchens' size, and made sure they're open to the rest of the unit." The gay contingent, he says, responded to the prospect of cooking while hobnobbing with guests. Pierce also expanded the terraces in many units to a whopping 7 feet by 19 feet.

"Because the gay community is gregarious," says Pierce, "we thought: Why not create a bunch of public spaces? We changed the design of certain units to incorporate a 9-foot-square front porch." Their research indicated that gays would actually furnish and use these porches.

All in all, the gay customer remained mostly true to stereotype. "They do demand a higher level of design," Pierce says. "So we put in a lot more detail. Nicer columns, nicer paving patterns." The result, judging from renderings, is a handsome development, not overly original, but "upscale" in that sun-drenched Florida way.

Inevitably, there has been some backlash. When Patrick shared the proposed "gay-friendly amenities" with the Sun-Sentinel, it set off a Howard Sternish outcry among some readers. "Hmmm," posted one on the newspaper's Web site. "Gerbil pens acceptable to neighborhood covenants? KY dispensers in the bedrooms?" Another poster pointed out that, if you substituted "black" or "Hispanic" for "gay," the whole idea would be branded as racist. (Patrick has since left the project for unspecified reasons.)

Gay comedian and columnist Bruce Vilanch recently satirized the project in a thinly veiled Advocate piece about the fictional "Wavering Facades, the world's first gated and secured metrosexual community: Anyone caught on the premises with an unmoisturized face or elbow will be escorted to the front gates."

Perhaps understandably, Ellis is close-mouthed these days about the focus grouping: "We don't want to build something that will be interpreted as specifically designed for the gay population," he says, apparently less committed to commitment ceremonies than he was four months ago. And the project's slick new, Flash-enabled Web site would seem to confirm that Ellis and crew are newly wary of depicting the project as "too gay."

Or, for that matter, gay at all.

On the Web site, most of the code words ("open-minded") have vanished. As have clear indicators that Wilton Manors is not Everytown, USA. In the animated intro, a few same-sex couples (easily confused with chortling straight buds or gossipy wives) zip by so quickly you'd be forgiven if you missed them in the crowds of happy heteros. Only one pair -- two preppy guys cozying up on a Vespa -- seems particularly Wildean.

Bill Murray, the media director of the Family Research Council, a prominent conservative group that opposes gay marriage, was struck by this: "At what point in the recruitment process, will [the marketers] expose themselves and their desire to create a largely gay community? It doesn't seem like the company thinks it has a very good idea because they're hiding from the fact."

Stephanie Blackwood, who co-owns Double Platinum, a New York gay marketing agency that helps companies such as Procter & Gamble and America Online tap into the $450 billion gay market, has a more reasoned reaction: "The site is very ambiguous, which is not an uncommon strategy. It allows [a gay person's] filter to tell him those are gay boys in the pool together, whereas a straight man will just see two guys." This approach, known in advertising circles as "gay vague," became popular after early attempts to run explicitly gay ads in the mainstream media backfired. The famous 1994 Ikea television spot, in which a loving, squabbling gay couple shop for tables, was quickly pulled due to bomb threats.

The site's vagueness is entirely strategic. "We spoke to a lot of experts," says Jim Ellis. "One marketing company would say, hit the gay market in the face. And another company would say, don't even go there." He opted to barely go there.

As a result, says Blackwood, the site may trigger a different backlash: from disappointed gay buyers. "I'd be lying if I didn't say there's a risk the Web site might alienate gay buyers. When given a choice between an ad that speaks to me vs. one that speaks to my straight neighbor, I'll choose the ad which acknowledges I exist."

Ellis knows that the 17 to 25 million gay American market not only exists, but is extremely desirable. (Readers of the Advocate earn an average income of over $100,000, and are four times as likely to earn over $200,000 than the general population.) Will he tweak the Web site, given such risks? "We'll play it by ear," he says. "Adjusting the message as we see fit, depending on the feedback."

When asked if he thinks his project will appeal to gay couples in, say, Alabama, who are afraid to hold hands in their hometown, who might see it as an oasis of acceptance, especially in this election year when gay issues are dividing the country, Ellis is vague, or possibly naive. "You know," he says, "I'd never thought of that."

The funny thing is, he may be sincere.

Those of us who think about such things have noticed that 2004 is a particularly volatile moment for gays. Gay activists have enjoyed recent victories, from the overturning of Texas' sodomy law to the consecration of V. Gene Robinson as the Episcopalians' first gay bishop. But the biggest victory -- the wave of "civil-disobedience" gay marriages that swept the country -- has galvanized the pro and anti sides more than ever.

At one end of the fear spectrum are the poker-faced "policy debates" of conservative groups like the Family Research Council determined to push through the proposed constitutional amendment restricting marriage to heterosexuals. At the other, unhinged Christian groups who counter gay protesters' cries for "Equal rights!" by shouting "Jesus Christ!"

In the midst of this chaos, the sunny gates of Wilton Station seem to be touching a chord, coincidentally or not. The first wave of advertising pulled in over 3,000 requests for more info, well exceeding the developers' expectations. Of these responses, far more came from the Advocate's 105,000 readers than from the New York Times Magazine's audience of 1.7 million.

The project -- which, after all, is still just a construction site -- has not yet caused a blip on the radar of high-profile conservative groups. The Concerned Women of America have no official comment. Nor has the Family Research Council urged its supporters to protest. But it seems inevitable that, if Wilton Station does trigger a trend -- especially if "married" homosexuals with children set up house in such enclaves -- the idea of a (mostly) gay gated community won't escape scrutiny.

"We realize that gays and lesbians have to live somewhere. As Americans they can live wherever they want," says Murray of the FRC. He adds, "We would never try to force them into de facto prisons behind gates. The problem arises when they try to force public policy to recognize their relationships as more than what they are."

Murray sees Wilton Station as an example of the homosexual lifestyle presented in a deceptively positive light. "Really, there should not be a public sanction of these [gay] communities. People say, look, aren't these [lifestyles] wonderful? The reality is: They aren't if you look at the facts." The FRC claims, for instance, that children reared by heterosexuals, specifically married ones, experience lower rates of drug use and arrest.

But even if Wilton Station is spared the immediate censure of the FRC or America's Concerned Women, its gay residents won't have to wait long to be condemned: immediately next to the site is Wilton Manors' First Christian Church. "Are you aware that God's words say it is an abomination for man to lie with another man?" asks its pastor, John W. Stauffer, by way of greeting. He describes his church as "evangelical and Bible-believing," and, with no encouragement, goes on to quote Romans 1, which could only be called gay-friendly by the extremely charitable. "Our church is a lighthouse in a dark place," Stauffer explains, "a place for sick sinners who have banded together." He clearly feels the town will get a lot sicker when hundreds of affluent homosexuals move in on the other side of his wall.

The pastor confesses that he's looking forward to the challenge of converting their reprobate minds. (He has already persuaded four of his flock to give up gay sex.) He plans to mobilize his special volunteer unit, "Evangelical Explosion," to visit the residents of Wilton Station, and ask chatty sinner questions such as: "If you died, do you know for sure that you'd go to heaven?" When reminded that Wilton Station, much like heaven, has a gate to bar intruders like him, he pauses. "Well, we could stand out on the corner there ... if they're in their cars, they may be hard to get, but we'll get them somehow."

When told of Stauffer's plans, longtime resident John DeGroot laughs it off: "Everyone has the right to have their head up their ass. I guess some people really like the view."

Wilton Stationites may find it tougher to laugh. This source of irritation is not about to go away. The First Christian Church, which crams 400 people into its building twice each Sunday, has construction plans of its own: It intends to build a new overflow space -- and, eventually, a grand new edifice -- on land it owns across the street. And when that happens, if the Wilton Station dwellers remain reprobate, "We will welcome them again."

Of course, despite Ellis' projection that 60 percent of buyers might be gay, no one knows exactly how "reprobate" Wilton Station will turn out to be. As acceptance of gay life has grown incrementally (the current marriage furor aside), many young gays have realized they don't have to move to West Hollywood or Manhattan (or Wilton Manors) to find an identity, sex and love. "People are coming out in smaller towns and rural areas and leading openly gay lives," says Michelangelo Signorile, gay journalist and author of "Life Outside," a book about the expanding gay community. "There's a growing desire not to be cordoned off in a gay ghetto." Meanwhile, he explains, although ghettos still thrive, more gays and lesbians are leaving them to buy property in quiet towns in upstate New York, or Northern California.

And here is the most bizarre twist in the story of the gated community in America. As gays move beyond the concept of the ghetto -- the cluster mentality rooted in fear and segregated conformity -- the rest of the country seems to be moving toward it. On one hand, you have gay clone style (cropped hair, muscles, artificial tans); on the other, the gated community's approved flower lists and dog restrictions. The difference is that gay conformity grew organically from a need to strengthen identity. In a gated community, it's mandated by deed.

The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 have arguably been a factor; a lot of Americans now feel targeted the way many gays have all their lives. And the gated community, a refuge from chaos, fits the bill, even if it's not particularly "safe." In California, over 40 percent of all new developments are gated, and while nationally fewer than 10 percent of homes are currently behind bars, according to the Census Bureau's 2001 American Housing Survey, that number is growing.

And then there's Wilton Station. Largely gay and gated. Both segregated and integrated. Heteros and homos living together in a Tiki Hut of harmony. When you consider the spending power of the gay market, says Stephanie Blackwood, it is an "inevitability."

It will be interesting to see how Wilton Station ultimately affects both social and housing trends in this country. If it succeeds without attracting undue controversy, look for other money-hungry developers to clone the formula. You have to give Jim Ellis props for trying something new, which is rare in development circles. "We're rolling the dice in some aspects," he says, "but I'm past being concerned about whether this will be well received."

It will come down to the individual. "The more conservative gay people might find it very appealing," says Simon LeVay, a gay scientist and coauthor of "City of Friends: A Portrait of the Gay and Lesbian Community in America." "For them, it will be the ultimate of respectability, like moving to a gay area without having to deal with the raunch."

For others, Wilton Station's promise of escape may prove illusory. "There will be some people who will think I'll be safe in this little gated enclave," says Signorile. "If that's why they're doing it, it's a bit delusional. It's like creating a giant closet, and staying in it, instead of confronting the homophobia that's still out there."

Shares