It will come as no surprise to parents that kids who watch an excessive amount of TV will want Mom and Dad to buy them an excessive amount of stuff. But can heavy media consumption also cause kids to be depressed and anxious, and exhibit low self-esteem? Could it make your child's stomach ache or her head hurt?

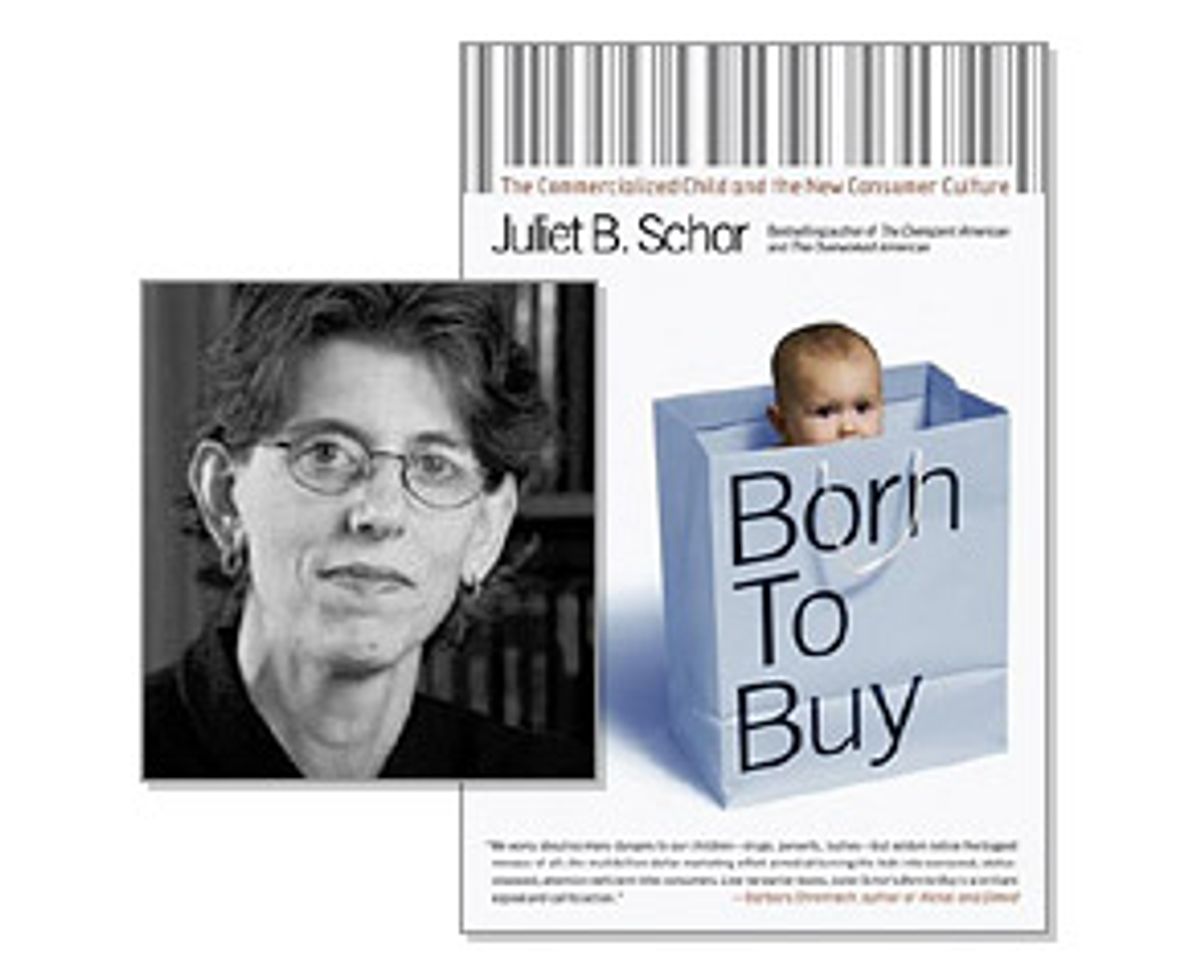

Juliet B. Schor, a professor of sociology at Boston College and recognized expert on consumerism, economics and family studies, says yes. According to a study Schor conducted from 2001 to 2003, consumer involvement affects psychological outcomes -- often in negative ways. Schor spent over four years studying the impact of marketing on children. She trailed marketers and researchers who focus specifically on kids, shadowing them at conventions, paging through their client presentations, and talking to them about the ethics of their profession. The results make up her chilling new book, "Born to Buy: The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture." "Psychologically healthy children will be made worse off if they become more enmeshed in the culture of getting and spending," she writes. "Children with emotional problems will be helped if they disengage from the worlds that corporations are constructing for them."

Schor talked to Salon on the phone from her home in Newton, Mass., about the pervasiveness of marketing in children's lives -- and why it makes some marketers feel like they're going to "burn in hell."

What was your motivation for analyzing the effects of marketing to children? How much of it was inspired by personal conviction and how much by professional interests?

It was really a combination. As I was working on my book "The Overspent American," I was struck by the growth of marketing to kids. Companies know that children are much more vulnerable to marketing than adults are, and that gives marketers the ability to establish brand loyalty at a young age. So today's kids are exposed to more commercial messages than adults are.

At the same time, I had two of my own children [a 12-year-old boy and 9-year-old girl] who just were getting to the ages where consumer culture was becoming more of an issue for our family.

I think we've all had the sneaking suspicion that advertising to little kids can't be good for them. But what makes this book revolutionary? Is it the age of the kids, the scope of the advertising, the methods used by marketers?

My "Survey on Children, Media, and Consumer Culture," which was taken by 300 kids ages 10 to 13 from 2001 to 2003, is the first study to look at the overall impact of consumer culture on children. There's been a lot of discussion about the rise of marketing, and there's been a lot of research on particular products -- for example, we know that eating junk food leads to obesity, we know that TV has a range of effects -- but no one has ever asked the question: Now that kids are immersed in consumer culture to an unprecedented degree, what effect is this having on them?

The natural tendency is to assume there is something about consumer culture that attracts problem kids and that's why they get so heavily into it. I tested that theory -- using a statistical model to rule out other variables -- along with the reverse theory that high involvement with consumer culture creates problem kids.

However, I didn't find that advertising and consumer culture attracted problem kids. That really surprised me. I only found that high involvement in consumer culture causes problems! Consumer involvement can lead to depression, anxiety, stomachaches and headaches, boredom, psychosomatic complaints, fighting with parents, etc.

The statistical findings do not tell us exactly how consumer involvement affects psychological outcomes, only that it does. We can speculate on that (I do in the book), but the bottom line is that it's not only what we eat, but also what we watch, what we aspire to, what media we let in our lives: All these things affect our physical and emotional well-being.

What are some of the defenses people in the children's marketing industry use to defend their work?

The most common idea is that marketers are empowering children, they're giving them information and appealing fantasies. But they're "empowering" them by saying things like, "If you buy this shoe you can jump as high as Michael Jordan!" "If you eat this cereal, you'll get amazing energy." And the fantasies are all product-focused.

Marketers like to tell us that children are incredibly savvy these days. They'll say things like, "Kids have 'truth meters' and 'lie detectors' and they know when you're trying to deceive them!" I don't think anyone will disagree that kids are more savvy about marketing than in the past, but that doesn't mean that they are able to be critical of advertising and persuasive messages in the same way adults can be.

Another defense is that parents always have the option of protecting children from advertising. They can turn off the television and just say no.

Well, can't they? Where do we draw the line between parental responsibility and societal responsibility?

I think there's no question that the responsibility lies in both camps. But the industry is saying the onus of responsibility is all on parents, which I think is a really disingenuous point of view. We've got single parents, we've got parents working longer hours than ever -- parents simply can't monitor what their kids are watching, doing, engaging with every second of the day. The truth is that the hottest areas of marketing right now are where parents don't have control, like schools, boys and girls clubs, churches, "good" television, etc.

In addition, marketers have figured out how to break down parental resistance, especially around food. Parents have a lot working against them, and it does get very hard to restrict, especially if families live in an environment where other parents are allowing this and permitting that. And what about the kids who, for whatever reason, don't have parents who protect them or watch over them? Do we, as a society, just say, "Too bad for those kids! We're certainly not going to do anything for them!"

Is there any truth to the claim marketers make that exposure to these messages teaches kids to be savvier consumers?

The little research I was able to find on this shows that the more exposed to commercial messages children are, the less critical they are of those messages. If we wanted to train kids in advertising literacy, we would do that. You don't do it by showing them commercials.

Why were kids' marketers so open to sharing their tricks of the trade with you?

I got my initial entree to the advertising world through the Advertising Education Foundation, which places professors inside agencies so that they can get a better understanding of what these agencies do. Ironically, part of the reason they let me in was that the industry felt it had a bad reputation in academia, especially in the field of liberal arts. The industry used to focus on business school grads, but now the kind of work they're doing requires students with a liberal arts and social science background. Then, once I was in, each marketer that I met seemed to be very willing to introduce me to other people that they knew. And truthfully, one of the reasons why I got as much information as I did is because I encountered a lot of guilty people.

What do you mean?

From the beginning, I didn't want to get into a debate about the ethics of what these folks are doing. I just wanted to find out what was going on, and assess how marketing affects kids. But there was a lot of spontaneous articulation of guilt and ambivalence -- I even had one kids researcher tell me she was going to "burn in hell"! Perhaps it's because I was in the outsider role. It was almost like I was a priest and these marketers were confessing to me! People were pointing fingers at other firms; marketers were all saying there's a lot of stuff going on that shouldn't be. But of course, everybody was implicating everyone else.

My sense is that there's just a growing sentiment within the field that things have gone too far. That view has been confirmed by a survey that was done by the Kid Power Conference in 2004. This survey of nearly 900 people in the field of marketing to kids showed that marketers felt that there was too much advertising to kids, and they felt that there was unethical behavior going on. We have a field saying it's unfair to market to kids until they're almost teenagers, and yet they're doing it.

But aren't marketers parents too? Did they talk to you about how they deal with marketing when it comes to their own kids?

Sure, some of them have kids. But many of them are young, and many of them end up leaving the field as they age and have kids. The people who have been there longer and have kids tend to be better at reconciling their personal lives with their jobs. They may have more faith in what they're doing, or they simply may be more tied to it in terms of financial reasons. In addition, there are a lot of men in the upper ranks of the kids marketing industry. Women may have more conflicts around kids; the men I met were able to compartmentalize better.

Was there a watershed moment in terms of kids and advertising?

Well, 2002 was an important year; it was the year that junk food marketing and obesity among children really became an issue. It started with food, because the junk food issue is not just a kid's issue. We also have an adult obesity issue. With books and movies like "Fast Food Nation" and "Super Size Me," fast food companies are coming under attack. The synergy of the adult and children's issues are propelling the children's agenda; since 2002, the momentum for a serious look at children's marketing has been growing.

Where does the Bush administration stand on kids and advertising?

The Bush administration has been very active in trying to derail effective change in dealing with the obesity crisis. They have tried to deflect attention from the connection between food consumption and obesity. The Bush administration gets huge sums of money from tobacco companies, cola companies, packaged food companies, and so far they've been quite effective in forestalling any meaningful action.

Basically what this administration is about is advancing and protecting the interests of corporations which are doing significant harm to kids.

Is America different from other countries in this regard? Are all capitalist societies heading in this direction?

It's hard to say. On the one hand, there has been an aggressive marketing push by food and tobacco companies in other countries, and consumption is soaring. They're developing many of the same problems we have in this country. On the other hand, you have countries like Sweden who ban advertising to children under 12, and you hear a much more serious discussion in the European Union about protecting children from marketing.

How do you protect your own kids from the effects of consumer culture?

When my children were very young, our family lived in a small town in the Netherlands for two years. I was so struck by how different childhood is there; the kids seemed fairly untouched by the marketing juggernaut, especially compared to the U.S. That was very striking to me, and it really set the tone for an attempt to do things differently with my own kids.

My son was brought up without TV, so we didn't have that experience of having him watch a commercial and ask us for the product. I suppose the most vivid anecdote about the early impact of consumer culture on our kids was this: We were sitting at the dinner table one day when our son began reenacting the script of the TV game show "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire." But he'd never even seen the program! He'd just picked up so much of it from school. This was a very powerful example of how, even if you restrict many things in your own home, your kids will still get exposed to advertising and marketing through secondhand transmission. Your own child doesn't have to have seen the commercial to be exposed to the product; he just needs to know another kid that was.

Do you ever worry that after years of being denied the pleasures of television, your kids will rebel and become media junkies?

I'm not going to deny that the "forbidden fruit syndrome" exists. But I think people overestimate that problem. Part of it has to do with how you institute a kind of alternative lifestyle, how you restrict consumer culture. If you just do it by saying no -- well, the stuff's all around them, resisting is going to be a tough experience for the child. But if you provide a rich environment for your kids, they're not going to feel deprived. Marketers have been very successful in tapping into imagination and creativity. They understand the importance of that to children. Some of the people who design environments for kids don't. Think about schools, for example: Too much about schooling is about enforcing curriculum and rote memorization. Of course kids are going to rebel against that. I think the idea of the forbidden fruit syndrome scares parents from restricting media in their kid's lives. Either way, your kids are going to end up highly involved in consumer culture, so you may as well try to control it.

Have parents made any significant impact on the industry yet?

There's been more legislative activity going on: bills being introduced, hearings taking place. Soft-drink vending machine sales have been banned or restricted in some districts and states. They haven't had any national victories yet but there have been small pieces of legislation passed at local levels.

I don't think many parents realize how much has changed since they were kids, and when they do, they're not too happy about it. There is a lot of sentiment in this country to protect kids -- we just need to get organized.

Shares