Paula Kamen has a headache. On the day I call her in Madison, Wis., where she's made a stop to promote her new book, "All in My Head," which is a memoir and a cultural history and a comic odyssey through the licensed and unlicensed health professions and a lot of other things besides, she rates the headache a 3 or 4 on a scale of 10. For most of us that would be a pretty bad day, possibly requiring three or four ibuprofens, a couple of grande Starbucks concoctions, dark sunglasses and a lot of grumbling.

But Kamen says she's feeling great. See, she got this headache when she was putting in her contacts in a Chicago hotel bathroom -- in 1991. Over the last 14 years it's been her constant companion, waxing and waning like the phases of the moon -- sometimes so intense she can't function at all, sometimes barely noticeable -- but never completely going away.

On one level, this is ludicrous: A woman gets a headache and writes a book about it. Kamen is able to appreciate the joke, up to a point. (She's not so delighted that a New York Times critic cited her book, without reading it, as an example of the glut of self-indulgent memoirs.) But Kamen's headache is enough to make you suspect there might be a God. If Jehovah chose Job to persecute because he knew that upright man's faith would never waver, maybe he had his own reasons for afflicting Paula Kamen with a never-ending headache. She was already a first-rate reporter on feminist issues as well as an aspiring humorist with a wry, sardonic tone.

That combination of elements has produced an improbable book, indeed almost an impossible one. "All in My Head" dramatizes Kamen's suffering without wallowing unduly in self-pity, and her journey along the highways and back roads of both Western and alternative medicine, while often hilariously rendered, will provoke anguished cries of recognition from anyone who's dealt with chronic pain (and the medical establishment's general befuddlement by it). More than that, as a reporter Kamen marshals most of what is now known or suspected about headaches and related disorders, and as a feminist she drags into daylight a half-hidden social phenomenon we all recognize but rarely talk about: the Tired Girls.

If you're one of the Tired Girls, you already know what I'm talking about (although you may not have known you belonged to a newly founded identity group). If you're not, then there's probably one or more T.G.'s somewhere in your life -- in your family or your circle of friends. A Tired Girl is that youngish woman, probably in her 20s or 30s, stuck in a cycle of pain and fatigue she may not talk about openly, even with her closest friends. She is known to cancel long-planned social engagements at the last minute, to disappear early in the evening, to oversleep, to spend beautiful Saturdays alone in bed. Like Kamen, she's constantly trying some new drug, some new massage or chiropractic technique, some new combination of Chinese herbs, some new diet.

A Tired Girl may suffer from migraines or depression or chronic fatigue syndrome (now called CFIDS) or fibromyalgia or bipolar disorder or the persistent, mixed-headache syndrome called chronic daily headache (CDH), which is Kamen's diagnosis. It's quite possible she has more than one of these conditions; scientists are now inclined to believe that these ailments (along with epilepsy and other seizure disorders) are related at the neurological level, and people who suffer from one are exceptionally likely to have the others.

Tired Girls are nothing new, and if you view the phenomenon with some suspicion, that's understandable. Victorian women fainted and had the "vapors"; the desperate housewives of the '60s self-medicated with Chardonnay and Valium. Medical testing couldn't "see" any organic source for these diseases, so they were often regarded as psychological in origin -- the result of female "hysteria" or sexual repression. These cut-rate Freudian theories found their way into the postmodern age, too: Feminists defined these female-coded illnesses as a form of political resistance to patriarchal oppression, while deconstructionists saw a cultural virus bred of millennial angst and spread by media overload.

I probably shared that skepticism myself, a dozen or so years ago. I never get headaches unless I drink too much or have a sinus infection. But for more than a decade I've lived with a woman who has 10 to 20 severe migraines in a typical month. In general terms, Leslie's diagnosis is similar to Kamen's, if less severe; she has CDH, but headaches are sporadic rather than constant. Like many other women, Leslie got significant but probably temporary relief from the massive hormone surges associated with pregnancy and breast-feeding (our twins were born a year ago). Leslie has taken many of the same prescription medications as Kamen -- mostly powerful psychiatric drugs with whopping side effects -- and been subjected to a lot of the same goofball psychologizing. (My favorite was the shrink who thought that because I was giving Leslie massages at night to relieve her pain-induced insomnia, I was a controlling boyfriend who was causing her headaches.)

Along the way, I've had to question my own preconceptions about these stereotypically female ailments, especially as I've learned that new, more sensitive brain scans now seem able to pinpoint their neurological source. As Kamen explains, it now appears that disorders like migraine and CDH result from a kind of wiring malfunction deep in the brain stem. Migraine, for instance, was recently described by one medical researcher as "a chronic-progressive disorder that may cause permanent changes in the brain."

Of course men suffer from chronic pain and fatigue as well; millions of sports fans got an instant education in this issue when Denver Broncos running back Terrell Davis had to leave the 1998 Super Bowl game with a severe migraine. (After an intranasal dose of a drug called DHE and a locker-room nap, he returned to score the winning touchdown.) But for reasons that aren't entirely clear, women are several times more likely to have these diseases, which has clearly contributed to the centuries-old perception that they're fragile and untrustworthy creatures, both physically and emotionally.

Paula Kamen thinks it's time for the Tired Girls to come out of the closet (or the darkened bedroom, as the case may be). Individual women can admit to pain and fatigue, she argues, without stigmatizing their entire sex. Hardly anyone argues that men should be excluded from the workplace as a group, despite their pronounced tendency to schizophrenic breakdown and random shooting sprees.

As I know very well, Tired Girls can be tough -- and Kamen has the scars to prove it. In her medical odyssey she's endured painful and useless surgery, gained and lost an enormous amount of weight, beaten a dependency on Xanax with large doses of "Antiques Roadshow." She's tried Botox, fig tea, a burlap sack from Peru (purported to retain energy from the baby who was born on it), "healing stones," a Russian masseuse who "beat the living crap out of me" and a vibrating hat from a TV infomercial.

In the long run, Kamen, 37, actually found the mental and emotional pain associated with her endless headache harder to deal with than the physical discomfort, as bad as that has sometimes been. She writes about the details of her personal life with considerable restraint (an example more memoirists should follow), but it's clear that her ordeal has made her love life very difficult. She's had boyfriends over this 15-year stretch, but none stays in the story for long. It has also strained and fractured friendships, made her financially dependent on her parents for a time (a humiliation for any adult), and rendered her unfit for any normal workplace.

Perhaps that last part was a backhanded blessing. If the headache literally disabled her, it also liberated her to research and write "All in My Head" as well as her previous volume, "Her Way: Young Women Remake the Sexual Revolution." (On that subject, Kamen reports that for many women, including herself, a headache is not an impediment to sex; if anything, the endorphin rush associated with a good romp tends to provide some relief.)

Almost none of the mainstream or alternative therapies Kamen has tried have worked, or at least not much and not for long. She still has her headache and, tragically, Jane Pauley's producer declined to put her on the air absent a miracle cure. But if "All in My Head" isn't the classic American narrative of How I Utterly Demolished All Obstacles in My Way, it might be something far more valuable. It's the story of learning to live now, with limitations and ambiguity and, yes, pain -- and not waiting until some future date when those things will be vanquished.

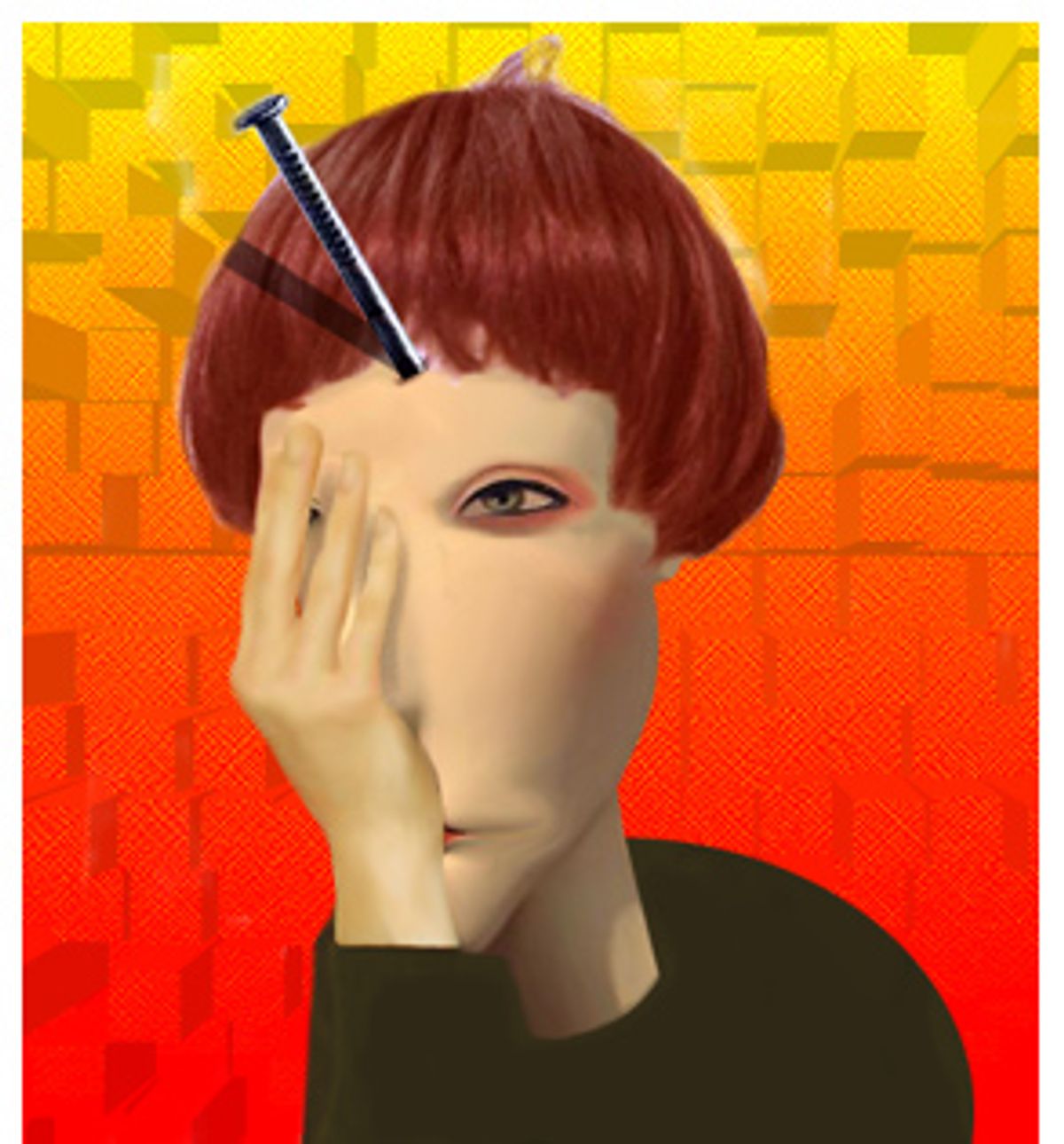

In Kamen's book, she describes her constant companion in various ways; sometimes it's like having ground glass in her eye, sometimes like having a railroad spike driven through her head, sometimes like having a barbed fishhook twanging at her optic nerve. (Yowtch.) Suffice it to say that her left eye and left temple always hurt (these days the right side can be pretty bad too), and 3 or 4 out of 10 is, as she says, "a great day." She's cheerful, funny and upbeat; she doesn't sound anything like that dreaded cultural icon, the Woman With a Headache.

This seems like such an important book to me -- it connects the dots on this issue of women and chronic pain in a way nobody else has done, and it's a remarkable personal story as well. I'm surprised that the media isn't all over you.

Well, it's still an invisible disability and there's still a lot of misunderstanding. People think it's just something silly, or something neurotic people have. William Grimes of the New York Times didn't read the book, but he did a story with the headline "We All Have Lives -- Must We All Write About Them?" It was about how there are too many memoirs, and he used mine as the prime example: I just had a headache and I'm so self-absorbed that I wrote a whole book about it. I must be an idiot.

Then there was this review in the Chicago Tribune where the critic wanted it to be more like a sex memoir. She thought I was just trying to write about an Important Issue, and that was why I did all that reporting. I really felt like that was essential. This issue is so misunderstood. If I just wrote about myself -- "I'm having a lot of pain" -- with no explanation of what chronic daily headache is, people would just think that I'm nuts. And then the issue really is about me, which I didn't want.

For a lot of people -- for a lot of women and, I predict, a lot of the men in their lives -- your "Tired Girls" chapter is going to be an epiphany. It's going to describe them, or someone they know, and connect them to this larger medical and social phenomenon. Have you heard that from people already?

I think it's just the beginning of people coming out about things like this. Someone e-mailed me the Web site of Rebecca Wells, who wrote "Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood," and she writes about having some form of chronic fatigue where she can barely lift a pen some days. Laura Hillenbrand, the bestselling author of "Seabiscuit," is now writing a book about chronic fatigue. So it's just the beginning of writing about these things that have been very, very stigmatized. It's almost the last thing to come out about: having weakness and vulnerability. It's one of the last taboos in our society.

Your book isn't one of those disease memoirs with a grand, dramatic solution. You parody that genre at one point: You're going to have a miraculous surgical procedure, marry the handsome doctor, and win the Tour de France six times. None of that happens. Basically this is the story of how you learned to live with this headache, rather than get rid of it.

Exactly. It's a lot about acceptance. It took me 15 years to accept that I had any kind of a disability, even though I obviously do. It goes against our culture so much to actually accept something. We mistakenly think that if you accept something then you're, like, dooming yourself. You're resigning and totally giving up. It's actually the opposite. In accepting it more, I can now live around it better. I can schedule things more efficiently and not cancel on people, the way I did when I was in denial about it. Acceptance of pain, in the last hundred years or so, has been discouraged by a lot of medicine. Pain has been considered fundamentally a psychological thing -- if you accepted it, that meant you were mentally attaching yourself to it.

Right. There's the Freudian concept, which you write about, that people with persistent or chronic pain are getting some kind of "secondary gain" from having it.

Exactly. It's so amazing that in 2005 that's still out there. That legacy of Freud, especially with chronic headache pain, has really lingered. I could go off on many tangents here: It's mainly experienced by women, it's literally in the head, where the mind is, and female hormones, which are known as the "crazy chemical," sometimes make it worse.

Let's talk about the gender issue, which is maybe the $64,000 question here. You go at this very directly in your book. People are going to have the reaction, whether they admit it or not, that this whole question of chronic pain and fatigue is a chick thing. It's a women's issue, shrouded in mystery and superstition. And you're saying, well, it's time to face that there's some truth to this stereotype.

Right. For this reason, I had a little hesitation in writing about this. But not much. One of the main justifications for excluding women from society has been that they're neurologically weaker, that they're "hysterical" and suffer more pain. Historically, that's how women were portrayed. Now, in recognizing the reality that women do get more pain and fatigue, it might sound like I'm anti-feminist. Actually, it's the opposite.

The time now seems to be right for us to be secure enough to talk about this. The women's movement has proven itself; we're strong and confident, we're in the workplace and the WNBA. It's also important to recognize that we're fully human. We're not superwomen. This generation believes that we're entitled to equal rights even if we're not perfect. It was a more delicate time in the '70s, and the job of the women's movement was to say, "No, we're not weak! We can be athletes! We can beat Bobby Riggs in tennis and run marathons and become astronauts! The body is truth!" That was an important mission, and now, with the third wave of feminism -- which I've written about since its beginnings in the early '90s -- we're recognizing a lot of issues we couldn't talk about as easily before.

Anyway, it's irrational for people to use this against women, this argument about us having more pain and fatigue, because men, neurologically speaking, have their own share of stuff. They're much more likely to have personality disorders, to have schizophrenia.

We have a pronounced tendency to kill people, don't we? That's posed something of a problem over the years.

That's true. So if you took that same logic -- that women have more pain, so they shouldn't be allowed to vote -- you might want to lock every man up as a preemptive strike. You wouldn't allow them even to enter a workplace, because of the risk that they'll go on a shooting rampage.

More seriously, the larger point is that everybody's different and there's huge variation. Not every woman has pain and fatigue, and not every man is a serial killer. [Laughter.] But we're defensive about it because of this history of it being used against us.

Can you summarize the current thinking as to why it appears that women are more likely to have these pain and fatigue illnesses?

Neurologically, women seem to process input differently, and it's more likely to translate to physical pain. It's not just hormones, because 14 percent of women in their 70s have a chronic headache problem. That shows that it isn't just the monthly hormone fluctuation, although for some women that's clearly a major trigger. For others it isn't as much. You have to understand that chronic daily headache or chronic migraine is basically a disorder where the brain is overreactive to stimuli, be it hormone fluctuation, stress, the weather or whatever. That's translated into pain; it's an oversensitivity.

It's complicated, but I should add a major point, which is one of the main reasons I did all this reporting. Just in the last several years, there have been these advanced types of brain scans, the PET scans and functional MRIs. With fibromyalgia and migraine and chronic daily headache, those scans show differences in the brains of people who have these things. So it's fascinating, because these things that were always considered to be invisible, and thus in some way not real, are now more and more considered visible. It's not like you can shine a PET scan on someone and see their pain, but they do detect measurable differences in the brain.

That's the beginning of a huge change, isn't it? As these diseases become visible, in terms of medical testing, that's almost an epistemological shift in the way they're understood.

Exactly. It's a major point. I've been to a lot of medical meetings, and on the highest level, neurologists are taking this very seriously. But then you find a lot of skepticism from doctors who haven't been in medical school for 40 years or whatever, and are tied to an older model of thinking.

Sure. I know very well, from my wife's experience, that some physicians -- and most shrinks -- still assume that chronic headaches have a psychological basis, or are rooted in the patient's personality. You write about this very movingly; you went through a period of self-doubt on that issue, basically doubting whether your symptoms were "real" or you were just inflicting them on yourself.

Oh yeah, definitely. You know, this is what our culture tells us, so much: It's really a question of mind over matter. You can overcome any sort of weakness through force of will. If you can find whatever the emotional block is, that's all it takes. It can be very hard to overcome that whole notion.

For a long time there was this whole medical conception of the "migraine personality," the overstressed, type-A, self-tormenting individual, generally a woman, who was sort of inviting these headaches. Has that idea finally been banished?

Well, in medical school today, they teach that that's totally not true. I interviewed a brain researcher, Dr. Nahib Ramadan, and he says there is no migraine personality. But it is true that if you have chronic headaches, a "co-morbidity" is often anxiety and depression. So it is more common to see those things in headache patients, but that's not their personality causing the headaches.

Well, I'd be anxious and depressed if I had headaches every day. I realize it's not quite that simple, but come on -- constant pain is going to change your "affect," as they say.

That's a problem when you go to doctors or shrinks -- you come in and you're visibly depressed because your whole life is falling apart due to chronic pain. So they blame it on depression. It's extremely common. There's very little understanding of this concept. Chemically, a lot of these things seem to be close to each other, and that's why some of the same drugs are used for depression and chronic daily headache.

Right. So the current thinking is that there's some neurological connection between a whole variety of disorders that include migraine and chronic daily headache, depression, epilepsy and bipolar disorder. Is that right?

Very good. You did your homework.

So people with one of these illnesses are more likely to have one or more of the others?

Yes, by far. If you have chronic daily headache, you're twice as likely to be bipolar than the average person. You're still talking about only 8 percent of people with CDH who have bipolar disorder, but that's twice the rate of the general population. That's a big focus of studies in the last few years, and I didn't know about any of that until I started doing research for the book. I just thought I was this freakish thing out in my own little world. I didn't know about the neurological connections. I didn't know if it was neurological. That's why I wrote the book.

Wow. So the whole time you're going to all these doctors and other health practitioners, you didn't really understand the science behind your headache?

Right. Because a headache becomes like an inkblot test to every doctor you see. You go to an alternative doctor and of course the problem is that you're eating wheat. I'm not even kidding. I heard this from many people: It was wheat, or dairy products, or toxins in the environment. The massage therapist insists it's a muscle contraction disorder; the chiropractor insists that it's all because of a spinal irregularity. Once I started going to medical conferences and interviewing people about all the new research and the new scanning technologies, it finally became a lot clearer.

Let's talk about your specific case. Even though you start your story by putting in your contacts on that particular summer morning in 1991 and getting a raging headache that never went away, you now don't exactly see it that way. In fact, you'd been building up to it for quite a while.

That's true. In reading books about people with chronic illness of all kinds, it's really common for people to point to one dramatic incident where it finally sunk in that something was wrong. In reality, for most people, it's something that develops under the surface. In my case, the nerves were becoming more and more sensitive over the years, and it got harder every year to put in my contacts. Finally it caused physical pain.

Right. And that pain launched you on this incredible odyssey. You see many kinds of physicians, you undergo useless and painful surgery, you take this amazing catalog of pharmaceuticals, including one that gets you addicted. You see several psychiatrists and psychologists. You visit every kind of alternative health practitioner I've ever heard of, and some I haven't. How many health practitioners, in total, have you consulted in the last 15 years?

Well, I have a list in one of the last chapters. I'd say it was at least 100, easily.

To anyone who's been through this, your litany of "off-label" drugs is going to seem grimly familiar. Klonopin, Paxil, Neurontin, Nardil, Depakote -- every few pages I would slap myself on the forehead and say, "Leslie took that one too!" Your experience, and hers, would not seem to be uncommon: You go to doctors and they nod and act all confident. They give you powerful drugs with all kinds of unpredictable side effects, and -- for a lot of people -- they just don't work.

That was a huge shock to me. I had grown up thinking doctors always had the answers. It sounds naive, but this was a time when alternative medicine wasn't big and questioning doctors wasn't really in the culture. I kept thinking it was just a matter of a few weeks. And I also thought for most of the last 15 years that I was the only person all these drugs didn't work for. It was a revelation to see studies that only about 50 percent of people with CDH respond to drugs, and to understand how crappy -- excuse me, how limited -- the options are.

There's been very little testing with CDH in general, so a lot of it is just anecdotal. Doctors prescribe things with very little explanation. I've had people read this book and tell me they had no idea the pill they were taking every day was actually an antidepressant. It's just so bizarre: You might be taking a blood-pressure medication one day and an anti-epileptic drug the next. And there are huge side effects.

You had a lot of dramatic side effects. What drug was it that made you gain so much weight?

That was Nardil, an old-fashioned antidepressant. It actually worked for about eight months, but without warning I became the Incredible Hulk. I was bursting out of my clothes, almost. For a single woman in her 20s, that was especially fun. It was like chick lit gone mad! You know, Bridget Jones complains when she gains seven pounds.

Then there are the drugs that just wrapped you in a mental fog, right?

Yeah, I started taking Klonopin without knowing what it was. I didn't know it was a major tranquilizer until I saw "Behind the Music" with Stevie Nicks many years later, and I was like, "Oh my God!" I thought I was neurotic because it was so hard to get off that stuff, and she's on TV saying, "Yeah, I was institutionalized for three months getting off it, and then I went into seclusion for two years on my ranch." So it wasn't just me.

Then you had nasal surgery. You went to an ENT specialist, and he decided you had a deviated septum and that was the cause of all this.

And two others agreed with him almost completely. It was just black and white with them.

And that made your pain dramatically worse in the short term -- but only slightly worse in the long term!

Yeah. That was the bright side. [Laughter.]

Then you actually became so dependent on a drug that you had to come up with your own rehab program.

Yeah, just flipping back and forth between three PBS channels. "Antiques Roadshow," that was perfect for my rehab. That was the worst, by far. That made Klonopin seem like nothing. That was Xanax. I was on a very low dose, so I thought it was just me, but that's even more addictive than Klonopin. It was pure hell, because a lot of doctors don't understand how difficult it is for people with pain to get off these drugs. When you try to lower the dose, the pain gets 10 times worse. It was like a chain saw cutting through my head. That was a low point, worse than the surgery, probably.

People may hear Xanax and think I'm a drug addict or whatever. I want to make clear that I never abused it, and I was the advocate for getting myself off of it. Nobody was telling me to.

You write that you never tried street drugs or recreational drugs to relieve the headache. You must have heard, anecdotally, that marijuana helps a lot of people.

Yeah. I don't know how much I should say on Salon.

You're among friends.

I never used it habitually. Like everybody else, you go to a party and somebody has it ... Like anything that's relaxing, cannabis has been used to relieve pain. It was a legitimate headache drug in the 19th century.

In my wife's case, for a while it was the only thing that really worked. We took this infamous trip to Quebec once, and the whole way north through New York state it was like being in a Cheech & Chong movie. I was driving through the Adirondack forests with this tremendous contact high, with the person next to me baked out of her mind. She finished off the dope before we got to the border, and there we were, greeting the Canadian immigration officer with this ganja stench billowing out of the car. But her neurologist told her that it helped a lot of people, and that he'd definitely prescribe it if it were legal.

Wow, that's all news to me. It was never prominent in my mind as a choice. But I am in Madison right now, so it's fortunate you brought it up here! [Laughter.]

Yeah, look into that. Although I should observe there are obvious downsides to consuming that much cannabis. Speaking of alternative medicine, you spent a lot of time in that world and you come back with a mixed report. What I got out of it is that you learned some valuable coping skills in that realm.

Right, it's not black and white. You see a lot of stuff now about how alternative medicine is totally great. They did a segment about chronic pain on the "Today" show recently, and all the sound bites were like: "Alternative medicine is great! Science says it helps!" In reality, you get what you can out of it, and there's some stuff to really be cautious about.

It was a turning point in terms of basic philosophies of coping. It's going to sound trite; a lot of it is obvious. But I had to learn the concept of detachment, and learn the difference between physical pain and mental and emotional pain. Before, when the pain got worse, I got all depressed and emotionally upset. Now I've learned to distance myself. I mean, easier said than done, and a lot of days it's just not possible. But in general my life is a lot calmer, it's not, like, this emotional roller-coaster ride. That has been extremely helpful.

You write about that very movingly: The hardest thing for you, in many ways, was not the physical pain itself but the way it made you feel and the way you judged yourself.

There's so much suffering, and so much of it is emotional and mental. You feel incredible guilt, you feel like you're the only one who has this. It's the opposite of hysteria, which is supposedly caused by all the openness, all the media attention that makes everybody believe they have these things. This is the opposite, where you believe you came up with this on your own, you invented it. These drugs should be working, so you're unresponsive. The alternative medicine should be working, so you're not thinking positively enough or working hard enough.

That's the type of suffering that I can help to relieve. I'm not a neuroscientist, so I'll leave the physical part to them. But I can help reduce that incredible guilt and shame and frustration.

Let's talk about the things that actually helped you, that had enduring benefits. A lot of those were really simple and commonsensical, right?

The most important thing for me now is exercise. Something free and simple! I get massage and acupuncture sometimes. It doesn't always do much, but it sometimes takes the edge off. And then, like, the most basic things: cold compresses, heating pads. I have this one heating pad that draws moisture out of the air, it's like the Cadillac of heating pads. An elastic band around the head.

You also found aromatherapy very helpful, right? Specifically the combination of lavender and peppermint oils.

It's absolutely incredible. At the cost of $50,000 and 12 years of my life, but it was probably worth it. Yeah, I always carry it with me. It has to be a high grade of oil, I didn't realize that in the beginning.

I had to put the book down and run into the other room to tell my wife about that. She goes everywhere with a little vial of essential oils.

There have been studies suggesting that it might go right to the limbic part of the brain, especially in women. It's great in the bathtub, I immerse myself in it constantly -- but the main thing is applying it right to the temple. I do that compulsively.

And just about the only medication you take at this point is pseudoephedrine, your basic over-the-counter sinus decongestant, right?

Right. It's like caffeine in that it's a good short-term solution that sort of calms things down. But it loses its effectiveness if I take it more than twice a week. I don't allow myself to take any pain medication more than twice a week, total.

So the triptan drugs that have helped so many people with migraines, like my wife? Drugs like Zomig or Imitrex, those do nothing for you?

Right. That's why doctors are researching chronic daily headache at last. A lot of migraine people have really been helped by those drugs, and people like me are left in a different category.

So these days you take no prescription medications at all.

No. I've made a choice to be lucid and in pain all the time. Usually I'll take Tylenol Sinus twice a week -- acetaminophen and pseudoephedrine. That's it.

Of course I should say that everybody's different. I use lavender oil and that might not do a thing for someone else. Some drug I hated might be the cure-all for another person. Everybody has to go through their own journey. But the thing I really learned from alternative medicine was to be aware of my own body -- what makes it worse, what makes it better.

What was the single craziest or dumbest thing you tried?

[Laughter.] It's so hard to narrow that down. The surgery was clearly the worst, but it was also inevitable. If I hadn't had it, I would have wondered the whole time if that would have done it. That and Xanax, definitely, were the disasters. In terms of alternative medicine? I don't know, there was just so much.

You did have a guy pour fig tea in your eyeball. May I just say that?

[Extended laughter.] Alternative medicine, unlike Western medicine, didn't harm me physically. It was more a case of the "mind-wallet connection," lots and lots of money. You know, you see somebody for 12 visits at $50 a pop, and it starts to add up. Then there was the vibrating hat I bought off a TV infomercial.

That was good too. This book is often very funny, even though it's about someone who's in pain almost the whole time. Did you have any hesitation in approaching it that way?

None at all. I started out wanting to be a comedy writer. The feminist stuff just sort of happened accidentally. It was always my main interest, and I didn't have to impose it here because it was inherent in the situation. There's such absurdity in having a disability that people can't see and don't believe is a disability, in going to all these doctors who are overpromising, the desperation that leads you to do anything, no matter how illogical, if it might get rid of the pain. The humor was also a coping mechanism too. Irony, for better or worse, is a distancing tool. When you get into the worst situations with this disability, and you're embroiled in it with no external perspective, a sense of humor is really helpful.

At a certain point you began to make contact with other people who had chronic pain, in some cases as bad as or worse than yours. That obviously changed your perspective.

I was sorry to see all this suffering that takes place in secret in people's lives. But it was extremely validating to see some of the same exact paths that I had taken. I thought I was a total freak in even having it, and then to meet people who had taken the same drugs and pursued the same therapies was amazing. You can become less self-absorbed when you see that, you can begin to see the bigger picture.

What's the one thing you would tell someone who's suffering from chronic pain, maybe in secret, and doesn't know what to do or where to turn?

That's a good question. It's like dating; you can't be totally desperate, because then you're likely to make bad choices. You have to make peace with it and accept it, and believe that you can go on with it. That makes you less vulnerable to charlatans and to invasive and dangerous procedures. And you have to live your life in the meantime. For years I always thought I would start living life after I was cured.

It's a balance; I'm not saying give up on getting relief. I'm still trying, definitely. But just see that a lot of life is lived with uncertainty and ambivalence. Having no pain doesn't always equal happiness, and having pain doesn't always equal sadness. A lot of disabled people come to realize that you can be happy and in pain at the same time. All of this is easier said than done! But don't put everything in your life on hold. It takes time to learn management techniques, and there will be inevitable chaos. It's not easy.

Are you at peace with the possibility that your pain might never really be cured?

I'm not totally at peace with it, but a lot more so. The odds are that I'll have this the rest of my life. The more research I've done, the more I see that pain that's constant, and that's gone on for years, sort of becomes programmed into the brain. There is a chance for, like, the Prozac of chronic daily headache to be invented. I do have some hope that there's going to be a drug someday that hits exactly the right neurotransmitter. But I have accepted that I can go on. There's a lot I can do, even in the worst-case scenario. There is the fear that it could get worse, and I'll deal with that if it happens. But the way it is now, I've figured out how to live with it. It's taken me a lot to get to this point.

Shares