Open "Dirty Blonde: The Diaries of Courtney Love" to almost any glossy page and you will see a picture of Love, or some simulacrum of her: a smear of lipstick, a doodled self-portrait, a poem, ephemera of her band, Hole, scrawled lyrics, a Polaroid, an artifact of her very productive and self-absorbed imagination. Calling the book a diary is a ploy to prey on the desire for access to Love's private thoughts. It's actually closer to a yearbook for a school with only one graduate; or maybe Love, albeit in the coolest, most punk-rock way, has succumbed to that most Martha Stewart of pastimes: scrapbooking.

The release of "Dirty Blonde" is an occasion to assess, after an absence -- she's not coy about where she's been; it's rehab, no Mariah-style "exhaustion" euphemisms for her -- where Love belongs on the topography of celebrity now. This is not to list her on the silly A-through-D high-school popularity scale that the proliferation of magazines and television shows devoted to the worship of fame have made the lingua franca, but to consider why Love provokes such a strong reaction.

Why we should care about Love's private thoughts given her blatant lust for publicity is the more pressing question that her book raises. There are several reasons Love is a touchstone: She calls herself a feminist when it is a label many women, famous or otherwise, do not wear proudly. But feminists are reluctant to champion her, as her choices have often been embarrassing -- or worse -- from playing Larry Flynt's wife in a controversial film to allegedly using drugs while pregnant with her daughter. Love also commits what amounts to a mortal sin by overestimating her own beauty, talent and achievements, believing utterly in herself in a culture where women's self-esteem is undermined at every turn. And then there are the lingering doubts that she earned that fame at all, having been married to a man more successful than she was, and having refused to fade away graciously after his death. Instead, she has held on even tighter, trying ever harder to prove her worth through her music, her film roles and now her book.

Love is adamant in her author's note about the fact that she "really hasn't written a book." She will find no argument here. This is a pastiche, an assemblage, the most Barthian of texts. Yet it is undeniably a reflection of Love's psyche, confirming that Love's allure lies in her glorious disarray. As they say in the South, she's a hot mess. She is not from the starlet factory where they mint Jojos and Rhiannas and other girls who can do that sweet-yet-sexy-yet-a-little-tough thing. She comes from an era when women played their own instruments and wrote their own songs, but she's not one of those Jewel-ish whiners or Sheryl Crow lite rockers. She's the real deal: a grungy girl punk rock star. And she can't quite shake that aura no matter how high her heels or how fancy her borrowed designer gowns.

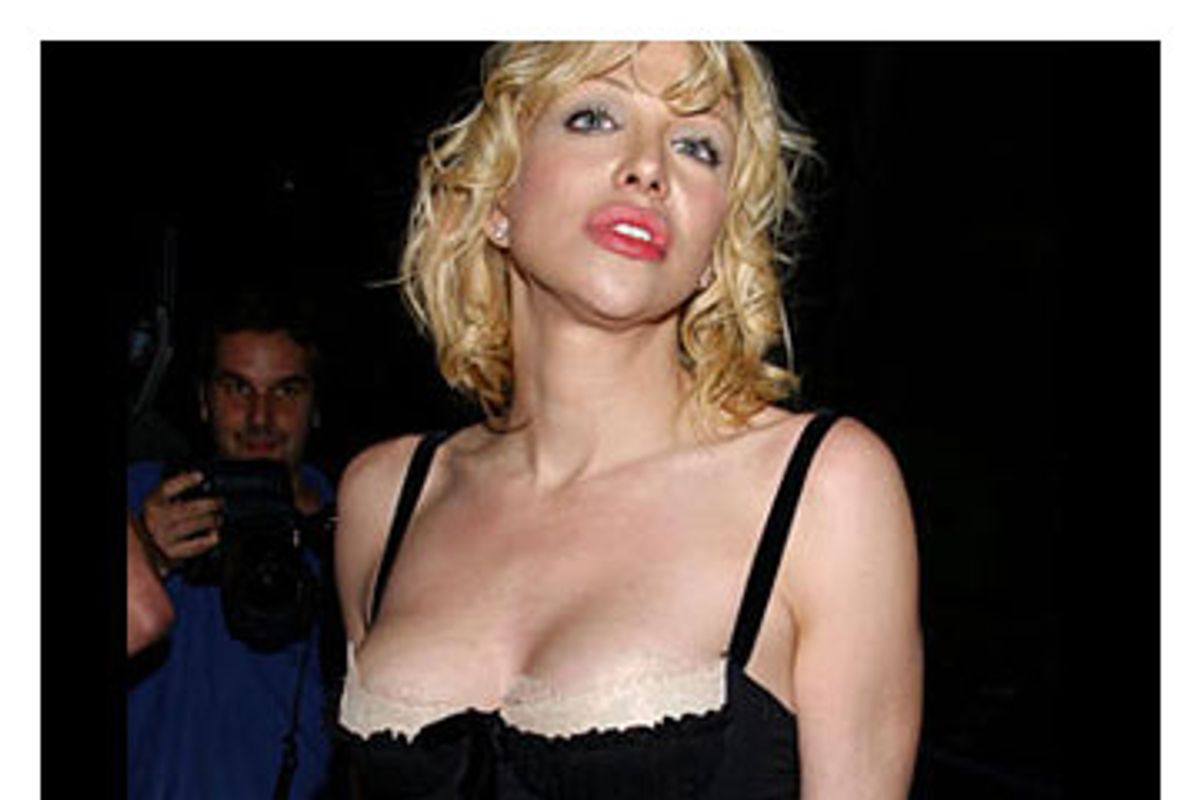

Even when she tries hardest to be glamorous and ladylike, there is something askew. It may be a trick of the eye, but in the slickest photos one looks for the slipped nipple, the reddish blemish, the mascara clump (and, yes, they are all here).

The book's inclusion of fashion designers Gianni Versace and Marc Jacobs -- a picture and remembrance of the former and a personal note from the latter -- is almost touching in its aspirational, please-make-me-over appeal. Just imagine Love begging them to hose her down and fix her up, commanding them to make her pretty on the outside. The first album Hole released, "Pretty on the Inside," paid ironic homage to precisely this idea: In a culture obsessed with appearances, especially for women, who cares if your insides are ugly or angry? If you still put on your makeup and go through the motions of being a good girl, will anyone notice? Implied, of course, is that the reverse is devastatingly true: Appearing in public with your messed-up insides showing -- something Love frequently does -- definitely gets noticed.

She's characteristically blunt about deserving attention, male and otherwise: "I love being famous. I fucking enjoy it so much. Why do I have to explain that? Because no one else has it. Because it's a fight. Because its psychicly [sic, sic] charging. Hey. Because I get off on it." She's a fame junkie, and evidence of her ongoing habit is everywhere: In her friend Carrie Fisher's introduction there is a jotted list of celebs who have called her that day, and in the acknowledgments ("Trudie and Sting," "Edward Norton," director "Brett Ratner," etc.). To revel in being famous is unseemly, though it seems almost quaint since the arrival of the Paris Hiltons of the world -- those skinny things who have become famous for just being famous, whereas Love has actually garnered critical acclaim for performing music and acting in films. Still, she is branded with the label given to those who enjoy the spotlight a little too much, derived from the world's oldest profession: publicity whore. It's precisely the combination of the patent enjoyment of her fame and her decision to act as if she were beautiful despite reports to the contrary -- thus the title of her early 1990s zine "And She's Not Even Pretty" -- that makes Courtney Love the object of sustained scorn and outrage.

Of course, there is also the idea that she has lasted past her expiration date. Some would say she has merely parlayed a personality into a career, coasting on the coattails of her dead husband, Kurt Cobain, thus suffering the wrath of millions of Nirvana fans, who can't (or just won't) forgive her for his suicide in 1994. Did she merely turn her train wreck of a marriage into fodder for her celebrity? The Cobain tragedy makes Courtney hard to love. Rock stars marry models, beautiful, silent creatures, not women like Courtney Love. Being smart, reckless, drug-addicted, outraged, independent, creative -- that's men's work, and she's got some nerve doing it.

Their relationship does not conform to other paradigms in popular music either. Country stars who intramarry are models for their fans, smiling archetypes of working romance -- or work and romance -- like Faith Hill and Tim McGraw. Even if Tim left Faith for Carrie Underwood tomorrow there is no way she would drunkenly show her tits in a Union Square Burger King, something Love did during the uglier days of her drug years (and it wasn't an isolated event). Hill is way too classy for that. She'd sing about her broken heart and appear on talk shows, dabbing at her eyes. And Is Beyoncé Knowles really dangerously in love with Jay-Z? Debatable. But if his body were found tomorrow under suspicious circumstances, Nick Broomfield, the documentary filmmaker whose "Kurt and Courtney" insinuates that Love murdered her husband, would hardly come sniffing around the Knowles' Texas McMansion armed with a camera crew and sinister allegations. Thug life is not for church-raised, mama-styled girls like Beyoncé. No doubt Hill and Knowles love their fame, even "get off on it" in some appropriate -- or even naughty, backseat-of-a-limo -- way, but neither of them generates Love's passion for fame, or the backlash against her celebrity. And can't you just imagine their scrapbooks? Yawn.

But there was a Courtney Love long before there was a "Kurt and Courtney." They existed parallel to each other, traveling in the same circles, as "Dirty Blonde" makes clear. There was a Hole and there was a Nirvana, and while everyone might fawn over Cobain's natural talent, no one can doubt her drive to succeed. In the manner of people who crave and lack self-discipline, Love constantly makes rules for herself: involving smoking (stop), reading (do), eating (don't) and, most egregiously, "Never let anyone see you be self-promoting." This is where Courtney Love diverges from Beyoncé, completely packaged and managed by her parents, who made her the Diana Ross of Destiny's Child and now pull the strings of her solo and film career. Or consider the ultimate pop examples of patriarchal manipulation, the Simpson sisters, Jessica and Ashlee. Their father literally controls their lives, from song choice to publicity to co-starring in their reality shows. Their images are perfectly composed, manicured and massaged. These days, when celebrity is cultivated and managed à la the Simpsons, Courtney Love's feminist status starts to look really radical: No man has ever had that hold on her. Have we seen her be self-promoting? A million times. Have we seen her naked? Sure. But we've never seen her bow down to anyone or anything, including public opinion.

The afterword to "Dirty Blonde" is written by third-wave standard-bearers Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, the authors of "Manifesta." One suspects Courtney is Cheshire-cat pleased when they call her "iconic" and laud her for telling 16-year-olds about feminism. But the afterword feels a tad awkward, like explaining to your mom, or your daughter, about Love's significance. Or what a riot grrrl was or why "bad" sometimes meant "good." Even their comparisons -- Yoko Ono, Janis Joplin, Marilyn Monroe, etc. -- are all old or dead. The song they quote from Hole's 1995 "Live Through This, "Doll Parts," which resonates with her body-image issues, to borrow the women's magazine terminology. "I want to be the girl with the most cake," Love sings.

But that, too, is a caricature of sorts. It's a remembrance of Love past, the snottiness, the baby doll dresses, the bleached-out hair. She's grown up since then, in her own way, beyond her new Hollywood veneer. And in doing so, she refuses to trot out her vulnerability in the way we demand celebrities do. She is a widow for whom there is blame but no sympathy, an addict who got but never came clean.

So put the doll parts away. These days, Love is sober and working on her second solo album, "How Dirty Girls Get Clean," with Linda Perry, who has squeezed massive hits out of pipsqueaks like Christina Aguilera and Pink, girls who would not be possible without the example of Courtney Love. Their "drrrty," mock-rebellious poses are like Precious Moments versions of the original.

Before she rushes into the future, though, let's linger on one more moment in Love's past. In 1999, during her lost years, Hole released its most mature work, "Celebrity Skin." It featured a song Love wrote called "Awful," which conjures her love of fame, her heartbreak, her narcissism and her incredible talent for self-promotion. It goes: "It's your life, it's your party, it's so awful/ Let's start a fire/ Let's have a riot! yeah it's awful/ It was punk/ Yeah, it was perfect now it's awful/ They know how to break all the girls like you/ And they rob the souls of the girls like you." It's a song about a culture that is awful, one that takes people like her and her dead husband and "breaks" them.

But it's ultimately about the gleeful pleasure Love takes in being awful, in her shamelessness and destructiveness. Those awful aspects are also what render her fearless, outrageous, unafraid and heedless of what anyone thinks or feels about her. The final lines of the song are: "They bought it all/ Just build a new one/ Make it beautiful." We did. And, makeover master that she is, she has. She even arranged her old stuff -- those relics of her fame and testimonials to her glory -- grabbed her glue stick and made a book about it. Go ahead. Open it.

Shares