Barbara Kingsolver published her first work of advocacy journalism at age 9, when her Op-Ed, "Why We Need a New Elementary School," helped pass a local school bond. She put writing aside to get a master's degree in evolutionary biology, which led to a job as a science writer, which led to a career as a freelance journalist. Journalism led to fiction; the rest is history.

"The Bean Trees," Kingsolver's first novel, was published in 1988 to great acclaim. With 2 million copies sold, it remains in print. Eleven others followed; all told, Kingsolver's titles have sold 7 million copies. Few American writers have managed to so seamlessly merge their radical politics and commercial success. "If we can't, as artists, improve on real life," Kingsolver says, "we should put down our pencils and go bake bread." Indeed, in her new book, "Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life," she does both.

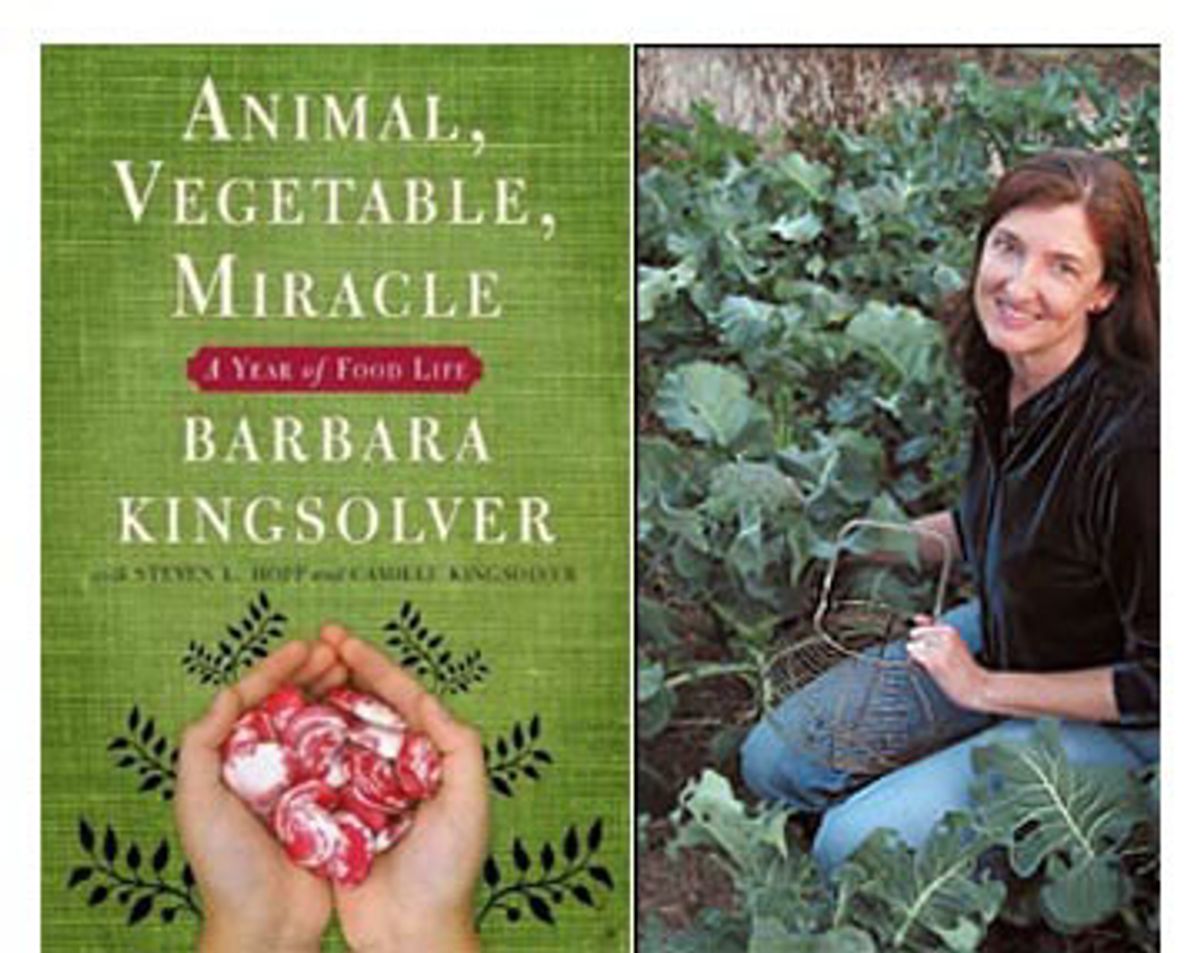

Part memoir, part investigative journalism, part cookbook, "Animal, Vegetable, Miracle" is co-authored by Kingsolver's environmental scientist husband, Steven Hopp, and their then-19-year-old daughter, Camille. Together they tell the story of the year the family spent eating only food produced on or near their southwest Virginia farm. The central narrative rings with Kingsolver's characteristic biting humor; Hopp's sidebars focus on the industry and science of food production. Camille's passionate essays, informed by youthful idealism and by her sharp intelligence, also include meal plans and recipes.

Kingsolver spoke to Salon from her farm about the interplay between activism and her art, writing in different genres, and the pleasures and pitfalls of writing about -- and with -- your family.

What made you choose the "American eating disorder," as you call it, as the focus of "Animal, Vegetable, Miracle"?

Surely it's normal for an artist's personal passions and artistic expression to coincide. Most of my books have been about the complex ways an individual depends on community. Having grown up in a farming economy, I'm fascinated by the subtle antipathies expressed by our country's urban culture against rural concerns. I'm interested in how that disconnection translates into today's disastrous food policies and dangerous eating habits. A lot of important conflicts of our time fall into place around the subject of food production and consumption. It made perfect sense to write about it.

Your descriptions of days spent harvesting and canning tomatoes, killing and dressing chickens and turkeys, were exhausting just to read -- not exactly the relaxed-country-living fantasy. How does the labor and stress of farm life compare to that of the writing life?

Some of the long days we described in the book were extraordinary, rather than routine: Obviously, harvesting animals is a once-in-a-lifetime event (for them, at least), and canning tomatoes in August is kind of the gardener's World Series. But in the day-to-day, farm work is stress relief for me. At the end of the day, I love having this other career -- my anti-job -- that keeps me in shape and gives me control over a vegetal domain.

Sometimes I see people at the gym bench-pressing until they turn purple, or running five miles in the rain after work, and I think to myself, "Who could push themselves that hard? Not me!" And yet, walking to the garden with a hoe feels like a tryst with a lover. I adore working up a sweat on a sunny day among the sweet potatoes. I love having used every muscle I own, making food for my family. That process is deeply compelling, probably coded into our DNA.

I never thought I'd get a laugh out of a botanical description of asparagus, but thanks to you, I did.

Hooray, that's my goal: to write pages a reader will want to keep turning. I'm a storyteller, not a minister.

Do you consider yourself an artist first, activist second, or vice versa?

When I sit down to write, I consider myself an artist. I'm consumed by craft -- choosing the word with the right mouth feel, reading sentences aloud to sublimate the rhythm, making flow charts of plot, working backward to plant the seeds for a perfectly revealed ending. When I attend a PTA meeting with a plan to reduce the school's carbon footprint, then I'm an activist. It's different work, with more direct expectations and a simpler vocabulary.

Do you think your commercial success has given you more freedom to write on subjects that might not otherwise find an audience?

I've never spent 10 seconds thinking about success -- 20 years ago, or now. Every time I start a new book, I'm thinking, "Oh boy, nobody's going to want to read this one." Seriously, look at my topics: child abuse; imperialism; the value of predators in biological systems; children bitten by snakes in Africa. Six years ago when I dreamed up this latest project, the world was all dot-com fortunes, virtual communities, and procuring every earthly thing anonymously out of the ether. Local food economies? Oh, brother. Imagine my surprise, now, to be releasing this book to a nation that's suddenly extremely excited about local food economies. What a shock, to be trendy.

What are the differences and similarities between writing fiction and nonfiction?

Writing this book as a nonfiction narrative was an obvious choice. What surprised me was how similar it felt to writing a novel, requiring all the same elements: lively scenes, compelling characters, plot, suspense and resolution. Creating these out of whole cloth, in fiction, is in some ways easier. For this narrative I had to create it from the finite array of events that actually happened.

The greater part of valor was choosing what to leave out. It's not a memoir in the strictest sense, because it's not really about us, it's about food production and local economies. The largest emotional events of the year, for us personally, are hardly mentioned, if at all: the death of Steven's sister; my slow recovery from a crippling accident; our family's adjustment after Camille moved to college -- these were not the domain of the book.

Nonfiction requires enormous discipline. You construct the terms of your story, and then you stick to them. "Because it really happened" is the worst reason to write anything, leading directly to ramshackle prose and the painful American custom of oversharing. I suppose 10,000 bloggers would disagree with me on that point. Perhaps here we've hit upon the distinction between blogger and author.

Did you have reservations about undertaking a project with your husband and daughter?

If the writing had created any discord, we would have shifted to Plan B: me writing the book alone. Family happiness comes first. As it happened, we strengthened our respect for each other's independent styles and depth of knowledge. We loved how it wrapped everything up together: inventing recipes, sharing references, bringing all kinds of creative challenges to the dinner table.

When I write about friends and family, I approach with extreme caution. I show them what I've written, and give veto power. My relationships are sacrosanct, which means keeping a firm boundary between private and public revelations. Lily, my younger daughter, expressed reservations over the scene about her 6-year-old proclamations on castrated stallions and daddies. But everyone told her it was the funniest scene in the book. So she let it stay in -- with the caveat that she's older and wiser now.

One of the book's unexpected strengths is that somehow, you avoid the moralizing and dogmatism that keep so many activists from connecting with the broadest possible readership.

I've never felt comfortable telling other people what to do. Even when friends ask me for advice, I tend to say, "What do you think you should do?" I think that's also a good way to write: create a world, invite people in, and nudge them toward making up their own minds.

That was critical with this book. Nobody wants to be told what to eat, not even by their mothers -- people get very grumpy about it. Before writing one word, I had to analyze that scenario. I decided it's because eating forces us back down into our animal selves, however else we might spend our lofty days. Eating is the second most personal thing we do. I had to approach the story as one animal talking to another: "Here is how I set out to feed my offspring from our habitat. Would we make it? Let me tell you!"

What do you hope your readers will take away?

Food is the one consumer choice we have to make every day. We can use that buying power in a transaction that burns excessive fossil fuels, erodes topsoil, supports multinationals that pay their workers just a few bucks a day -- or the same money could strengthen neighborhood food economies, keep green spaces alive around our towns, and compensate farmers for applying humane values. Every purchase weighs in on one side or the other. It just isn't possible to opt out. Otherwise, if you're going to eat food, you belong to some kind of food chain. The goal of this book is to reveal that truth.

It's not necessary to live on a farm to eat mindfully, but it's necessary to know farms exist, and have some appreciation for what they do. It takes a little background to recognize the social, biological and epicurean differences between CAFOs [Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations] and pasture operations, extractive vs. sustainable farming, or even what will be in season each month of the year. Amazingly, the outcome of responsible choices can be good health, money saved and a happy palate. Really, it's good news.

Shares