Children shouldn't use cellphones. No one should drink diet sodas sweetened with aspartame. And think twice before getting X-rayed with a CAT scan except in a bona fide life-threatening emergency. That's just some of the precautionary advice that epidemiologist Devra Davis, who runs the Center for Environmental Oncology at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, delivers in her new book, "The Secret History of the War on Cancer."

Davis, who is a professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health and formerly served in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, argues that the United States' $40 billion "war on cancer" has focused far too much on treatment, and not nearly enough on prevention. There's a lot of blame to go around here, and Davis serves it to up to the scientific community, the government, polluting industries and even cancer advocacy groups. For instance, in the late '60s, three years after the surgeon general declared that smoking causes cancer, the United States spent $30 million of taxpayer money to create a safer cigarette, essentially doing the tobacco companies' research and development for them. Needless to say, this effort failed, but it succeeded in giving the tobacco companies cover, assuring smokers that a safer cigarette was just around the corner.

Davis argues that again and again, from tobacco to benzene to asbestos, the profit motive has trumped concerns about public health, delaying, sometimes for decades, the containment of avoidable hazards. And, as in the current scientific "debate" about global warming, the legitimate need for ongoing scientific research about many possible carcinogens has been exploited by industry to promote the idea that there's really no need to worry.

In "The Secret History of the War on Cancer," we meet one of the foremost epidemiologists of the 20th century, who is revealed after his death to have been on the take from Monsanto to the tune of $1,500 a day, and we visit the site of former towns that have literally disappeared, like Times Beach, Mo., which since being declared a toxic waste site, has been incinerated, reduced to some grass, geraniums and tulips -- the only signs that anyone ever once lived there.

Yet, traversing this grim territory, Davis remains optimistic that much more can be done to prevent cancer. She's heartened by the work of advocacy groups like the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics and Breast Cancer Action, which asks that during this month of Breast Cancer Awareness you "think before you pink," since some of the companies jumping on the breast cancer awareness bandwagon actually make products that may contribute to the disease. And Davis is hopeful that the green revolution in everything from architecture to home-cleaning products to fashion to healthcare will not only help save the earth but will actually reduce all our toxic body burdens.

Salon spoke with Davis by phone from her office in Pittsburgh, a city that she noted used to be so thick with pollution that it was nicknamed "hell with the lid off."

In the U.S., one out of every two men and one out of every three women will develop cancer in their lifetimes. How have those rates changed in recent decades?

Deaths in the United States have fallen from cancer, because smoking has fallen so much, and smoking is such a major cause of cancer. We've also improved our ability to find and treat colorectal cancer.

The good news is that deaths are falling. The bad news is the incidence has increased for a number of forms of cancer, for example, testicular cancer. Lance Armstrong is the poster child for the remarkable successes of chemotherapy, but he's also emblematic of the dramatic increased risk of testicular cancer throughout the industrial world.

Testicular cancer in men under age 40 has risen 50 percent in a decade. What are the theories about why there might be such a radical increase?

In the United States and Japan, there has been a significant decline in the birth of baby boys. What does this have to do with testicular cancer? Well, there's a theory of testicular dysgenesis, which means that there is something on the Y chromosome that is transmitted to boys that is affecting their overall health, and it may affect whether or not a boy sperm works to fertilize an egg.

Something is affecting fathers' ability to make baby boys, which may also be affecting the ability of the boys that are conceived to become fathers. It may be affecting sperm count, which is declining. It may also be affecting development of testicular cancer, which peaks in young men in their 20s. And these things are likely to be related to early life exposures to hormone-mimicking chemicals.

What chemicals?

Pesticides, alcohol, lead and solvents have all been shown in occupational studies to reduce the ability of men to father boys and to increase the risk of birth defects in the babies that they have, including cancer. There's recently been a report from the Arctic Assessment of many more girls than boys being born. If something is affecting such an exquisitely sensitive part of human biology, then what else is it doing to us?

When we read about a study that says XYZ substance causes cancer in rats, how should we interpret it?

We differ with rodents by about 300 genes. That's it. The differences aren't nearly as big as some people would like you to think.

We use animal research to develop drugs. But when it comes to evidence that something causes cancer in an animal, something that might be used in our schools and homes, we say: "Well, wait. We better get proof of human harm." How can we say that we'll rely on animal studies when we're trying to invent drugs, and then deny their relevance to us when we're trying to predict, and prevent, human harms?

What's the alternative?

The alternative is to do experiments on people, or worse, which is what we are doing -- a vast uncontrolled experiment. We will never be able to answer many of these questions, because there is no control group. Who isn't exposed to cellphones? Who isn't exposed to aspartame? Who's not exposed to solar radiation? And that makes it very difficult to do studies of human health consequences. It really does.

We have a lot of natural experiments out there. For example, asbestos mining was a natural experiment, unfortunately, and it went on for far too long. We didn't start to control it until the '70s.

There are a lot of things that we're late to do. Why don't we have a national ban on smoking in public? Italy, Ireland, Bulgaria and Uruguay have banned smoking in public.

Why do you have concerns about aspartame, the artificial sweetener in many soft drinks and other low-calorie foods? What's a drinker of Diet Coke to think?

I can't tell you what to think: I can just tell you what I know, and what I recommend to my children.

In 1977, Richard Merrill, who later became dean of the University of Virginia Law School, was the chief counsel of the Food and Drug Administration, and he formally asked the U.S. attorney to convene a grand jury to decide whether or not to indict the producer of aspartame, G.D. Searle, for misrepresenting "findings, concealing material facts and making false statements" in aspartame safety tests.

This is not some left-wing group. This is the actual chief counsel of the FDA asking the U.S. attorney's office to convene a grand jury. It never happened, because by the time the grand jury was ready to be convened we had a new president. That president was Reagan, and within a month of Reagan taking office, he had a proposal from a guy you might have heard of named Donald Rumsfeld [who was then chief operating officer of Searle].

And Jan. 22, 1981, one day after Reagan's inauguration -- one day -- Searle reapplied for FDA approval. Prior to that, every single request for approval was turned down by all the scientists ever looking at the data. That's a fact. There's no dispute about that fact. And then, it gets approved May 19, 1981.

Remember what happened with the Reagan revolution? It was: "We need to get the government off our backs." One of the backs it got off of was suppressing the aspartame industry. Later, many of the people who worked at the FDA to evaluate aspartame ended up going to work for the company producing it.

So you tell people to avoid it?

Absolutely.

First of all, there's no evidence that it helps you lose weight. And there are people who drink a lot of diet soda. It's a question of a risk-benefit trade-off.

The thing that I'm most concerned about is the latest study from Italy. A typical rat study runs two years; that would be getting your rat to about my age: 60. People live now to their 90s. This study started their exposure when they were babies, like what we do now in the United States with aspartame, and let the rats live out their natural lifetimes until they were 3 years old.

And when they did that they found a significant increase in tumors that occurred only in that third year of life. Of course, the European Food Safety Authority, which sounds very independent, says the study is worthless. But I looked up the background on the people involved with the European Food Safety Authority, and many of them work directly for the food industry.

The Ramazzini Foundation, a toxicology institute, which did the study, is not known to be radical. Unlike most other sources of information in toxicology, it's truly independent. It is not funded by Monsanto. And what they found is that there is significant increase in lymphomas and leukemia, and that the increase comes not from consuming 800 cans of soda a day, but from consuming fairly moderate amounts of aspartame in these animals' lifetimes. They had 1,800 animals, and some of them were just consuming the equivalent of two cans of soda a day, two yogurts, 10 pieces of chewing gum. And at that level of consumption, there was a significant increase in cancer, and it only showed up in older rats.

How have recent court rulings made it harder to try to prevent cancer?

We have gone backward since the '70s. In the '70s, in the decision on lead in gasoline, the court said we could use experimental evidence that something was a threat to human health in order to prevent harm. The court repeatedly ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency could use theories, models and estimates to prevent harm.

Now, we have to prove that harm has already happened before taking action to prevent additional harm. In the area of cancer this is a travesty, since most cancer in adults takes five, 10, 20 or 30 years [to develop]. It means that we have no opportunity to prevent cancer, because we must prove through human evidence that it's already happened. I think that is fundamentally wrong public policy. Ninety percent of all claims now for toxic torts are denied.

What the court decisions have done is to make the burden of proof close to impossible when it comes to human harm and environmental contamination.

Given that, when people choose products or foods, what guidelines do you think that they should be employing?

I think prudent precaution -- moderation in all things, including moderation. Sometimes when we look under the kitchen sink, and when we look at the products that we use on our bodies, or when our 5-year-old asks us for cosmetics, sometimes we have to say no.

Efficiency is generally going to reduce your toxic burden. You can do more with less. In my own home, my kids joke, I buy baking soda by the 10-pound bag. You can use baking soda for just about anything that you can use Comet cleanser for. And vinegar does a whole lot as well. There are a lot of very simple things like this that we can do, and move away from some of the more complex synthetic materials.

Just yesterday I was walking in Squirrel Hill, and I saw a very lanky 15-year-old boy, whose mother had asked him to weed the concrete driveway. He was lollygagging down there with a spray can of a pesticide wearing sandals. And I happen to know his mother, and I said: "Have you looked at the label on that thing he's using?" She said: "No." I said: "Well, you might want to think about it, but I don't recommend that someone his age uses pesticides at all. And spraying with that may not be a good idea."

What potential carcinogenic exposures are you especially concerned about?

I'm very, very concerned about the overuse of diagnostic radiation, especially in children. For example, CT scans [CAT scans] of the head and the abdomen. Now, obviously if you have a child with a potentially fatal head injury or a stomach bleed, you can use a CT scan.

Most people don't realize that a CT scan to the head of a baby can give you between 200 and 4,000 chest X-rays at once. And therefore they should be used in a much more limited way. And guess who agrees with me? The American College of Radiology has called for reducing the use of diagnostic radiation in children.

Why is it being so widely overused?

Because doctors are ignorant. Emergency room doctors don't know how much radiation is involved in the CT scan to the head of a child.

We think if we've got a technology we have to use it, and we tend to assume that there is an inherent goodness to technology, and whatever harm that might be associated with it is vastly outweighed by the benefit. And we have many, many examples where that has turned out not to be the case. And diagnostic radiation to infants and children is one example.

You would caution parents to have them use it sparingly?

If it's an emergency, that's different. But if it's not an emergency you should ask whether there is some alternative that would involve ultrasound or MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] that would therefore not expose the child to radiation. On a healthy young person, do you really want to have a CAT scan of a knee or achy body parts, when it may be possible to get information without it?

What does the history of work-related exposures to carcinogens being covered up mean for workplace safety today?

The United States today has the smallest percentage of men and women working in blue-collar jobs in modern history. Just as an example, computers today are made in the United States by robots, which is called "lights-out manufacturing." Where people are exposed to computer manufacturing is in Asia. So, we've exported our dirty jobs. In the United States today it's not so much of a problem.

But polar bears in the Arctic are showing up as hermaphrodites with toxic waste in their bodies that would qualify them for burial in a hazardous waste site. How do you think that they're getting exposed to these pollutants? They don't work at factories. But they are at the top of the polar food chain, and pollutants go up through the food chain stored in fat from the little fish to the big fish to the walrus to the polar bear. Ultimately, they're making it very clear that pollutants don't need passports, and that you can't ban toxic materials in one nation. It has to be a global policy.

A recent report from the American Cancer Society found that breast cancer death rates are falling. To what do you attribute that?

Some people think it's because of hormone replacement therapy, which, if it's true, is extraordinary. The question is: Is it a true decrease? One possibility is that we stopped doing as many mammograms. There have been budget cuts, as you may have heard. With fewer mammograms, then you'd be finding less breast cancer. A third possibility is that there is a real decrease because fat-seeking pesticides, like DDT, are at the lowest point in American history.

Yet, Gen Xers are at greater risk of developing breast cancer than their grandmothers?

When Gen Xers reach their 40s, the risks are higher than the risk was for their grandmothers when they were in their 40s.

I've developed a theory of Xeno estrogen, named for the Greek word for "foreign." Basically, all of the risk factors that have been identified for breast cancer, except radiation, are related to the total lifetime exposure to hormones. So, the earlier in life you get your period and the later in life you go through menopause, the more hormones you're exposed to in your lifetime, and the greater your risk of breast cancer. The more alcohol you drink in your lifetime -- alcohol is highly estrogenic -- the greater your risk of breast cancer. The less exercise you get -- exercise lowers the amount of circulating estrogen -- the more estrogen in your life. The more fat in your body, the more estrogen, because fat is estrogenic.

Endocrine disrupters in the environment certainly have been shown to affect the chances. Certain plastic, phthalates, some pesticides, arsenic, mercury, diesel exhaust, all of these things have been shown to increase the risk. Some things that are widely used in cosmetics, like parabens, are estrogenic. So, the sum total of natural and synthetic estrogen in your lifetime affects your risk of breast cancer.

Why are more young girls going into puberty at an earlier age? Why are more young girls developing breasts? There are several reasons to think that hormones in personal care products may be playing a role, particularly for breast cancer in young black women.

Some black baby girls were found to have breasts between ages 1 and 3, and when Dr. Chandra Tiwary, who was a pediatric endocrinologist with the Air Force at Brooks Air Force Base, interviewed the mothers he found out the mothers were all putting a cream on the girls' scalps. And we don't know what the hell for sure was in all those creams then, but Dr. Tiwary found when the mother stopped using the cream, the breasts went away.

If something is making the breasts grow in a baby, what is it doing to others in terms of promoting growth at the wrong time, or promoting an improper or excessive amount of breast growth that could lead to cancer?

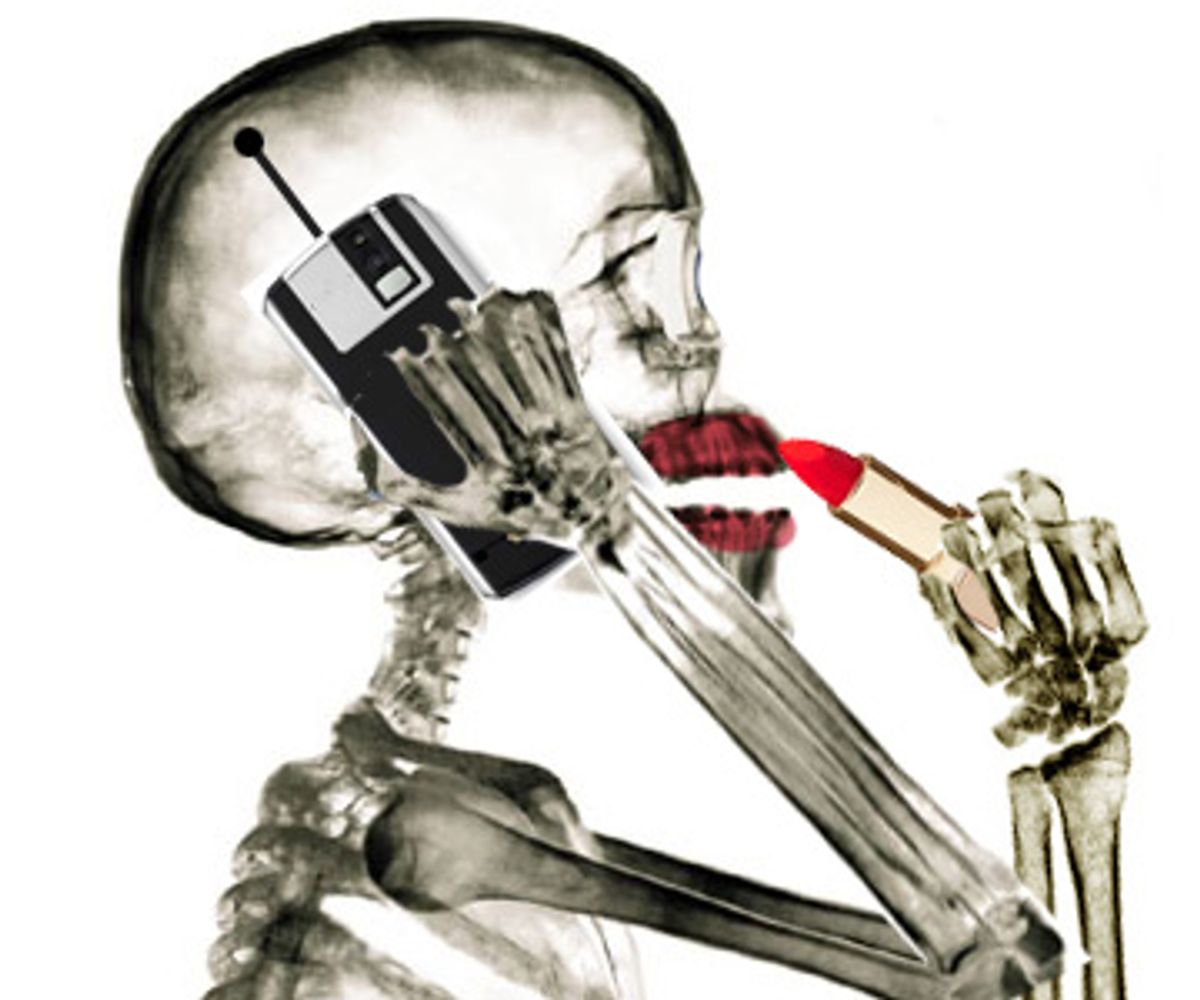

Why are you concerned about cellphones?

I can't tell you that cellphones are safe, and I can't tell you that they are harmful. That's the problem. The reason I can't is that there isn't really independent information, and the cellphone industry has been so quick to spin information.

Studies that you hear about that don't find a risk are often extremely limited, like the Danish Cancer Study. That's a ridiculous study. Anybody who used a cellphone for work was kicked out of the study, which is crazy, because those are the highest users. And they put all of these people together who were not using it for business -- the high users, the low users -- and they didn't find anything.

A study just released from France showed that people who used a cellphone for 10 or more years have double the risk of brain cancer. And people who owned two or more cellphones had more than double the risk of brain cancer. The level of this increase wasn't what we call statistically significant, but that doesn't mean that it wasn't important.

I do advocate that people use them with speaker phones, and with a head piece, and that children not use them. In Bangalore, India, and in Scandinavia, they recommend that children not use cellphones. It's illegal to sell a cellphone to someone under the age of 16 in Bangalore, India.

A cellphone is a microwave, and basically the reason your ear gets hot is that you're warming it with a microwave. You like cooking your brain? How would you like to cook the brain of your child? We're not cannibals. We shouldn't be doing that.

Shares