My husband, Neil, and I had just sat down to lunch when we got the call. We'd spent the morning reading books about infertility and assisted reproductive technology, and we were drained, exhausted from months of waiting on a stalled international adoption list and overwhelmed by the question of whether to pursue infertility treatments.

"You won't believe this," said Neil. "We have a referral, if we want it."

If we want it? Of course we wanted it. There was nothing we wanted more.

We'd started trying to get pregnant three years before. It took six months to conceive my first pregnancy, which I miscarried in the first trimester. I gave up my morning latte and the occasional glass of wine, took up acupuncture, practiced restorative yoga, went on vacation, charted my temperature and cervical mucous, peed on ovulation sticks and had lots of sex. Nothing worked.

I desperately wanted to be pregnant. I fantasized about breast-feeding, about walking around my neighborhood with our baby tucked into a cotton sling across my shoulder. So I kept trying, at least for a while: two rounds of the infertility drug Clomid (known for its unpleasant side effects) and artificial insemination. I hated every minute.

Adoption seemed the perfect alternative. I needed a baby, and there were babies out there who needed mothers. I didn't think I could handle an open private adoption, entailing ongoing contact with my child's birth mother. Domestic adoption, through the foster care system, usually involved older children with troubled pasts and ties to family. With international adoption, babies are relinquished by their birth parents and live their first months in orphanages, or in what our Boston social worker called "nurseries." She handed us a list of possible countries: Guatemala, China, Russia, Ethiopia, India.

India.

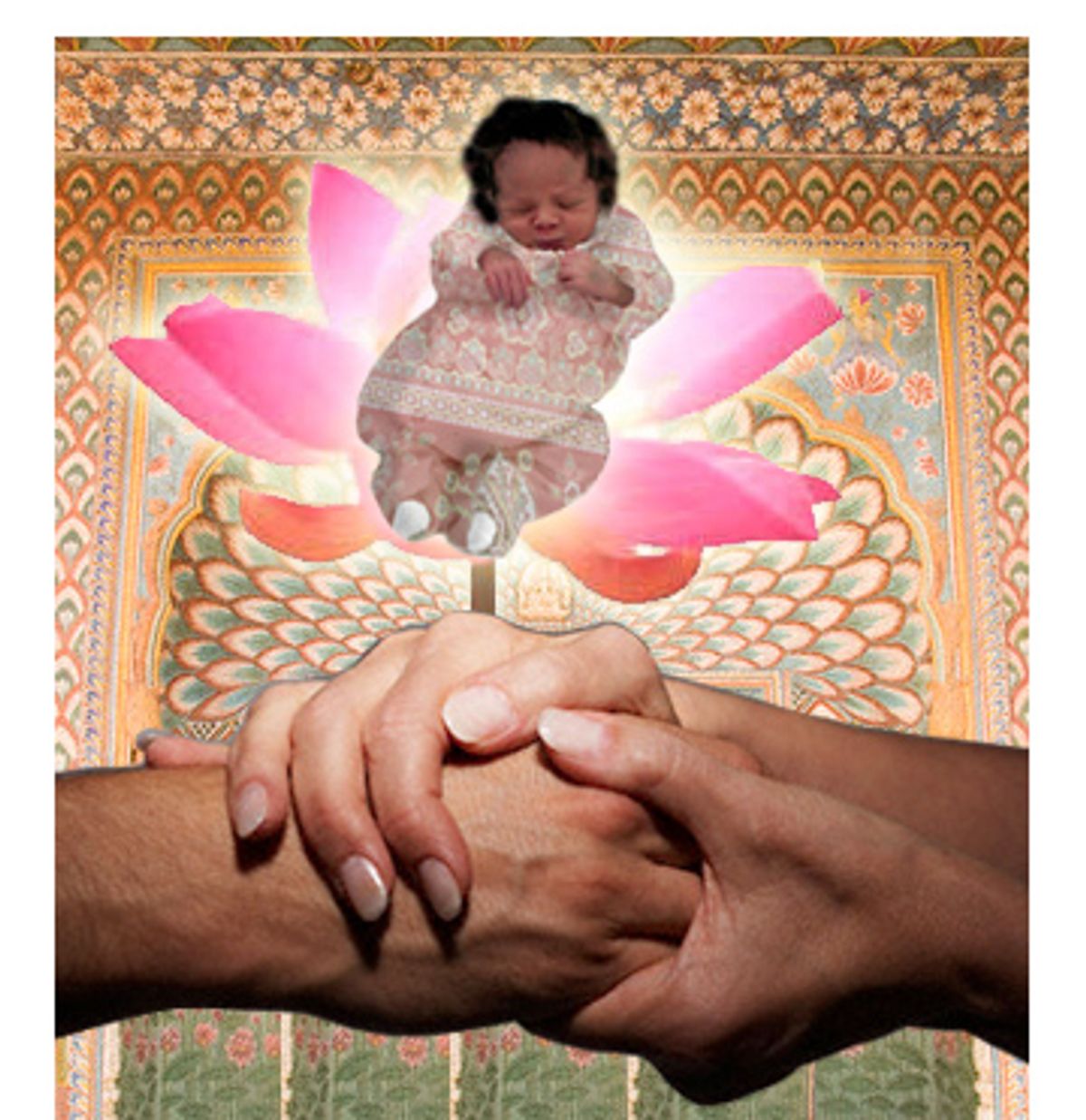

We made the decision immediately. India fascinated us; it was a place that, truthfully, we'd already romanticized. I'd practiced yoga for a decade, and Neil and I were both interested in Eastern philosophy. Since marrying, we'd talked about spending a year in India. Now I imagined traveling there to meet our daughter. I traded in my daydreams about pregnancy and childbirth for a new fantasy: flying into Mumbai and taking an overnight train to the orphanage, dressed in an Indian blouse and worn leather sandals; the moment in the orphanage when my eyes would lock with my child's and, together with Neil, we'd become a family.

As we waited for our referral (and as I watched my friends and acquaintances get pregnant, one by one), Neil and I told ourselves we were better people for having chosen adoption. I didn't care about having a child who looked like me or shared my genes. We became enamored with the idea of adoption, talking ourselves out of more critical, complicated readings of the institution. Over winter break, we took a chunk of cash we'd been saving and traveled around India for a month so we could better know the country where our daughter would be born.

A full year after that trip, there was still no referral, no baby selected to be matched with us. What's worse, we'd recently heard from our social worker that no referrals were likely in the near future. There had been an upswing in domestic adoption in India -- a good thing -- but the result, combined with bureaucratic inefficiencies, was that although millions of Indian children live in orphanages, the pipeline of young, healthy orphans going overseas had just about dried up. We might get a referral sometime in the next six months, but there were no guarantees. It could be years, or it might never happen. Faced now with the prospect that I might miss out on parenting altogether, I started to wonder whether I'd given up on infertility treatments too soon.

And then, we got the call.

"I'm looking at a picture of her right now," said our social worker. "She's gorgeous, a beautiful child. The biggest brown eyes I've ever seen."

Relief filled me: an objectively cute child. For months I'd worried -- privately, and with deep shame -- that we'd be matched with a child who wouldn't strike me as adorable. A child I wouldn't love fast or ferociously enough, who would feel like someone else's daughter, one I'd want to give back. I worried that my heart might not be big enough to love any child placed before me. I didn't need a child to look like me, but I did need a child who felt destined to be mine.

"And she's healthy!" our social worker proclaimed. Undernourished, but healthy. Relinquished by her unwed mother at birth.

A healthy baby. I hardly registered that the girl was much older than we'd expected and agreed to -- 21 months rather than 12 -- and that she had speech delays.

Two years earlier, we'd spent all of 10 minutes discussing whether we might adopt an ill or special-needs child. The adoption form asked us to check off which health problems we could handle, and we checked "none of the above." Like most parents, we wanted a healthy baby. Since we were adopting a child from an orphanage, we knew that "health" was relative, and we expected our daughter would need help catching up with nutrition and language acquisition. More than that we didn't think we could handle. Of course, if we adopted a healthy child and she became ill, we would do anything for her. But with adoption come choices, boxes of illnesses to check or leave unchecked, and our preference was for a child with no serious health issues.

We were too excited to eat. Neil asked for the check and threw some cash down on the table. We had to get to the computer to see the photo of our little girl! I was high, euphoric. I was about to see my baby and, in a few months' time, hold her in my arms.

Looking at the photo for the first time, we saw that she was undeniably beautiful.

Along with the photo were pages of handwritten documents with measurements -- height and weight and head circumference -- which, as first-time parents, didn't mean much to us. Instead, we concentrated on the photo and the overall assessment: healthy. Neil and I had discussed the challenges of adoption at length, but we had focused on the emotional and cultural challenges, not developmental. How would we talk to our child about her birth mother? About having a different skin color and birth heritage? Could she feel both Indian and Jewish? Did those identity labels even matter? Health, we assumed, would come with good nutrition and medical care and our love and attention.

We celebrated the following night at a fancy Indian restaurant. We ordered the vegetarian tasting menu, and I tried not to think of the price of the meal. Or of the larger ethical issues surrounding international adoption: the extreme poverty that causes girls and women to give up their babies and the global inequalities that lead those babies to homes overseas. Although we couldn't help being excited that our dream of having a child was about to come true, Neil and I knew we were going to benefit from an unwed mother's impossible choice.

And yet, we celebrated. How could we not? We devoured strips of fried okra, the restaurant's signature dish. We drank Kingfisher beer and held hands across the table, seated up on the balcony, surrounded by tables of wealthy Indians and Indian-American families. My baby, my baby, my baby, I saw in each of the children's faces.

On the way home, I bought a parenting magazine. I sopped up the pages like the grease on the okra. The next morning we went shopping. I needed to connect to the baby, and buying her clothes was the closest I could come to touching her, bathing her, caring for her myself. After years of waiting, my daughter was coming. Touching the garments, folding them neatly in their plastic bags, I began to believe in the adoption, to believe this baby was mine. In what felt like pure formality, we sent the documents about the baby to a renowned New York pediatrician who specializes in international adoption.

And then we heard back.

"This is a special-needs referral," the pediatrician explained. "She's tiny. She's not even on the chart. She's suffering from malnutrition. And I'm very concerned about her head circumference. The brain develops from birth through age 2, and this child is already 21 months. And you won't be bringing her home for five or six months. This child is going to be seriously delayed. I want you to know what you're getting into."

"I don't understand," I began. "Our social worker and the orphanage consider her a healthy child. And this is supposed to be the best orphanage in India. They feed the children on demand. How could she be suffering from malnutrition?"

"Well she's not sick, so in that sense she's healthy. But research has shown that some children do fine in an orphanage setting and others -- no matter how good the care -- can't handle living in an institutional setting. They crave the intimacy of a parent-child relationship, and without that they start to go downhill, becoming depressed, withdrawn, like animals in a cage. This child was fine when she was born, on the chart for height and weight and head circumference. I consider this a case of failure to thrive."

I wanted to turn her words around and make them change shape. I wanted to stuff the words back into her mouth.

The pediatrician told us our daughter would need speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy. She would need early intervention.

"Early intervention? What does that entail?" I asked.

"The state will send someone to your house several times a week. She may need ADHD medication, assistance with speech, language and fine-motor skills, and then special education services once she's ready for school."

"Isn't this something we can do on our own?" I asked. "We're willing to do anything. I'm going to be home with the baby. Neil's taking a semester's parental leave. Couldn't we catch her up?"

"Oh you're sweet," said the pediatrician. "Sweet, and well-intentioned and naive. Listen, I'm sure she's an adorable child. Perhaps you should get a second opinion."

I didn't want a second opinion; I wanted my perfect daughter back. Back home, Neil went online and looked up head circumference and height and weight charts for rural southern Indian girls. She wasn't on that chart either.

I wished we were different people, the kind who would welcome this child, welcome the risks, with no questions asked. I wanted to help her, to make her OK. But what if I couldn't? Could I love her anyway? To a parent, this question must be unthinkable. You love your child no matter what, accepting all limits and gifts. But we had a choice, and the magical thread that had spun us around this child for the previous two days was beginning to unwind and tangle. Until we signed the referral papers, until an Indian judge granted us legal guardianship, she was not ours. We had a choice.

Neil and I had each had our share of hardships. Neil's mother died suddenly when he was in college, and his father died when Neil was in his 20s. My father had violent rages, and my mother stayed with him; I no longer speak to my parents. But such difficulties are mere speed bumps when compared with the poverty we saw in India. I couldn't imagine what this little girl had already endured. Neil and I were, unquestionably, the lucky ones.

Are we bad, selfish people for wanting our luck to continue, for wanting a child with a normal IQ? How could we refuse a baby whose only "fault" was to be born to a mother too poor to keep her? And yet, we knew that if we said no, she'd likely be matched with another American couple, one more eager to welcome this child despite the risks.

Neil didn't think we should accept the referral, and I couldn't bear the responsibility of being the one who said we should. I wanted to be the person who would take on such a parenting challenge, who would prove the doctors wrong. I wanted to be the one who would convince Neil, and myself, that this child was ours. But already, in my mind, she'd become a burden. She was no longer adorable and perfect. Her needs frightened me.

Neil, a university professor, asked a colleague in the medical school who specializes in brain development issues to evaluate the referral. The colleague reported that there is a high correlation between a head circumference far below the mean and below-average intelligence. Mental retardation was a definite possibility. Another doctor, an expert in international adoption and the father of children adopted from India, told us she might be able to bounce back, but that she seemed different to him from a typical child in an Indian orphanage.

Our social worker read the reports, and reassured us that she wanted the best match for everyone, that if we didn't feel right about this referral we shouldn't take it. The baby would be matched with another family, and eventually we'd be matched with another child. But, she said, this baby might be fine.

It wasn't the baby who was lacking something, but I. Although I understood the fears, my weaknesses and selfishness were still fanned out in front of me like playing cards. I was filled with sadness, but also with growing certainty about what choice we would make.

We turned down the referral.

Our social worker couldn't predict when the next referral might come, and I wouldn't wait patiently any longer. My hunger for a healthy child felt primal and all-consuming. We'd waited long enough; I wanted a doctor to fix me.

The next day Neil and I called an in vitro fertilization clinic in Denver. A week later, still adrenaline-fueled, we flew to Denver for a series of medical exams. We began to conjure up a new dream: a biological baby from the Denver clinic and an adopted baby from India. Whichever comes first, we told ourselves. Hopefully both. While remaining at the top of the waiting list for an adoption referral, we signed up for our first IVF cycle two months later, after I'd be finished with a writing residency in Tucson, Ariz.

In the desert, I thought about babies nonstop. The one we lost to miscarriage, the one we said no to and the ones we hope to have soon. I couldn't get the photo of the baby in India out of my mind. The child I decided not to mother has made her mark on me. I am more aware of my limits and weaknesses, more in touch with my strengths.

In April, we found out that I was pregnant. I was shocked, elated. The years of waiting melted away. The morning of my first ultrasound I confided in our social worker about the nascent pregnancy, and she said the adoption would have to be put on hold for a couple of years. The baby inside of me, already mine, needed me now. That afternoon, we saw a heartbeat pulsating on the ultrasound screen. Still, I remain haunted by images of the little girl to whom I said no.

Shares