How does any obsession begin? A few too many viewings of "Taxi Driver" and Jodie Foster's hot-pantsed visage were indelibly tattooed on John Hinckley Jr.'s brainpan. We all know people -- decent, interesting, otherwise catholic in their curiosities -- who watched the O.J. Simpson trial every day for a year. Even my straitlaced, newly retired father became demented after he was confined to one floor of his house with a compound fracture of his tibia; for six months all he wanted to talk about were the multiple failed escapes of his only constant companion, an overweight teddy bear hamster with a bad case of wanderlust.

It's repetition that feeds obsession, cutting a groove in your head that you just can't get out of. Regardless of developmental imperatives, the same principle holds true when little kids want to hear the same story over and over again. And again.

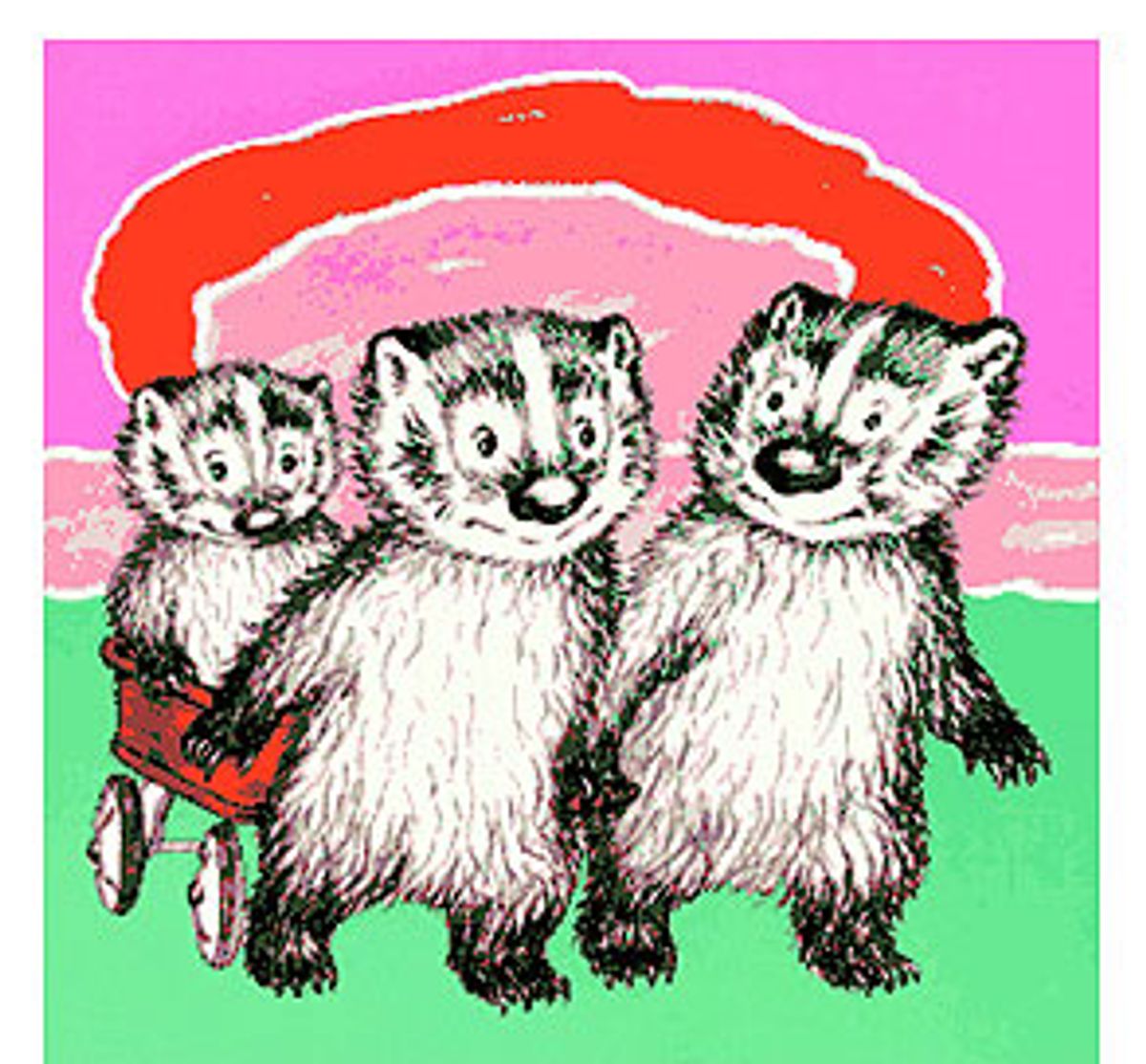

Thus began my relationship with Frances, the whimsical heroine of Russell Hoban's '60s-era series of children's books about a family of badgers. It started simply enough: Last year, "Bedtime for Frances" was the book my then-2-year-old wanted me to read to her ad nauseam. There are (mostly craven) ways around a lot of repetitive behavior; we all know that books and blankies "get lost." Solar-operated organs with microchips preprogrammed to play polka tunes can be jammed into a deep, dark closet or given away.

But I read about Frances obligingly, even relievedly -- at least hers wasn't a story created to serve the mindless television and movie character product market. It wasn't foolish, insipid or boring. It was far from any of those things. It was, in fact, irreverent, sly, droll and enigmatic, the product of a superior children's-book-creating mind and an earlier age, a book in which parents could sit in front of the television eating cake, offer a piece to a kid who should already be in bed or threaten to spank -- and still, everybody was perfectly well adjusted. This was a book I could read a lot. In fact, the Frances books, all seven of them, are the only books I can read over and over again without wanting to puke like a marathoner.

Why I never read Frances when I was a kid in the '60s, I don't know. But I did read another of Hoban's fictions in a college lit class. "Riddley Walker" is a post-apocalyptic fable set in the fifth millennium, when nuclear holocaust has catapulted civilization back to an Iron Age (the iron, in this ominous case, is dug up and salvaged from the machines of our own time) and language has been corrupted into a degenerated but tellingly poetic pidgin. Described by the New York Times as "lighting by El Greco and jokes by Punch and Judy," "Riddley Walker" tells the story of a 12-year-old who stumbles into a quest for the answer to one of the essential human questions: How did we get here, and how do we get out?

Mulishly dismissive of anything that might be construed as science fiction, I resisted "Riddley Walker." And yet it drew me in. I just couldn't shake off Riddley's epiphanic discovery of the hart of the wood in the ruins of Canterbury Cathedral -- in Hoban's resonant linguistic purling, the "hart of the wood" is the "heart of the would," the human will. It's both our grace and our downfall. Five millenniums of my life and two children later, I thought of Riddley Walker and his search for existential understanding while I was reading "Bread and Jam for Frances." "Aren't you worried that maybe I will get sick and all my teeth will fall out from eating so much bread and jam?" Frances, after several meals of bread and jam on demand, asks her mother. "I don't think that will happen for quite a while," replies her mother. "So eat it all up and enjoy it."

Frances is, in a way, a sunnier precursor to Riddley Walker. At the heart of her would is the age-old challenge of childhood: becoming socialized. Joining the human race is never easy, and the delight of Frances is that we get to watch her jostle with her conflicting desires and feelings with all the gracelessness and longing that we felt ourselves when we were small, and that we now witness so often in our own evolving children. Everything does, eventually, turn out OK for Frances, but hers are the types of everyday OK that ring true: A candy bar meant as a birthday present for her sister is squeezed to mush before Frances can finally bear to give it up. A sleepless night, with all of its attendant spooks and threats, ends when she finally gets sleepy. And betrayed by a crafty playmate, a sadder but wiser Frances finally decides she'd rather be friends than be careful. In this age of waning skepticism and entrepreneurship, isn't that the same sentiment that makes marriage and business partnerships possible?

Demonstrating the evolution of Frances' ego and superego against the delicious tidal pull of her id is the recurring theme of sibling rivalry with cute little Gloria, who is introduced as a newborn in the second of the Frances tales. At first Gloria is nothing but a tiny furry face in swaddling, but her influence in Frances' world is immediate and huge. As if preempting the possibility of being forgotten by demanding to be noticed, Frances escalates her bids for attention -- first she sits forlornly beneath the kitchen sink, then she marches through the living room shaking gravel in a can and singing lustily. Finally, disgusted by a lack of clean laundry and a dearth of breakfast raisins, Frances announces she'll run away. And she does, provisioned with Oreos, to a secluded spot under the dining room table until she overhears her parents' sotto voce lament regarding her absence.

As Frances' mom and dad know, love-bombing an ambivalent older sibling is the standard approach when the new child is a fairly oblivious baby. But as Gloria grows and her relationship with Frances gains complexity, Frances' sense of Gloria's personhood as well as her own gains problematic depth. In "Best Friends for Frances," Frances easily shrugs off the plaintive weeping of playmateless toddler Gloria for the greener pastures of baseball with her friend Albert -- only to have to resort to playing with Gloria after all when Albert dumps her for a "no girls" game. In "A Birthday for Frances," the title itself is a sly comment on Frances' psychological growth, since the birthday in question is Gloria's, now nearing school age. Frances' jealousy takes root in pitiful asides to her imaginary friend ("That is how it is, Alice ... your birthday is always the one that is not now"), kicks under the table and a long memory for past slights, but her grudging resolve finally disintegrates at the prospect of being the only one not to give a present to her little sister. An epic struggle ensues in Frances' tormented conscience when the cake is brought glowing to the party table. After singing under her breath, "Happy Chompo to me/is how it ought to be ...," Frances demurs, but it takes the entire party's encouragement to get her to relinquish the coveted Chompo bar in her grasp. The scene resembles nothing so much as an emergency crew coaxing someone down from a building ledge.

By the time "A Bargain for Frances" rolls around, Gloria is a person whose opinion has enough clout to sway Frances' worldview. In this penultimate Frances story, Frances is saving her allowance money (all $2.17 of it) for a real china tea set painted with blue flowers. The cunning Thelma bilks Frances out of her savings by persuading her to trade for Thelma's old plastic tea set. Though an equivocating Frances cheers herself on the walk home with another of her inimitable songs ("Plastic cups are all right too/Just as good as china"), it's Gloria's pronouncement that Thelma's tea set is "very ugly" that clarifies Frances' opinion. And it's Gloria who tips off Frances that Thelma too covets a china tea set with blue flowers -- just like the one for sale in the window of the local candy shop for $2.10 -- and moves Frances to retaliatory action.

As these dramas unfold over and over again at bedtime in my house, I'm struck just as frequently by the understated wisdom of Frances and Gloria's parents. In fact, I'm fascinated by their admirably nonchalant and sometimes seemingly retrograde parenting strategies. How was it that they learned to wield such sure authority with their children that, when a youngster stomps into the living room shaking a can of gravel, Father simply says, "Please don't do that," and the child just stops? There are no negotiations, no power struggles, no offerings of distractions or toned-down alternatives; there is no yelling. And how do they manage to stay so cool and productive in the midst of massive birthday party histrionics? Frances is known for regularly inserting a provocative comment into a conversation -- a hint, say, that another child she knows gets an outrageous allowance, or a question about the unmentionable origins of certain foodstuffs then on the dinner table -- but Father and Mother invariably deflect Frances' fishing by changing the topic without missing a beat, not to mention forgoing the indulgence of some sort of "validating conversation" straight from the parenting handbook that will eventually turn her into a whiny brat. Frances' parents understand that they're the ones in control: They're undeniably loving, but they're also firm. Consequently, their children appear to be secure, creative and ultimately kind as well as perverse and clever.

Frances' are parents who know to offer multiple kisses and pile everything from a "tiny special blanket" to a sled next to the bed of an insecure child, but they're also not afraid to tell a kid to solve her own (minor) problem when it interrupts the television show they're watching. What's more, these are parents with no neurotic attitudes toward sugar -- there's cake or chocolate pudding or some other sweet in every book, always generously applied. "You may be sure that there will always be plenty of chocolate cake around here," says Mother Badger, after Frances has already chowed down all of her Oreos under the dining room table.

And they spank. Or at least spanking is threatened in some way at some time in their household, enough so that in response to her sleepless father's grouchy question, "And do you know what will happen to you if you don't go to sleep?" Frances knows what the answer is likely to be. But the truth is, Frances' parents never get caught spanking anybody. They only float the possibility, disembodied but ominous.

Last July, while stuck in rush-hour traffic, I listened to the audiobook version of Frances for over two hours. My daughter had long since fallen sweatily asleep in her car seat; I had plenty of other tapes, or I could have just switched on the radio. Instead, I inched my way across the Golden Gate Bridge while fantasizing about Father and Mother Badger and their brood. Why is Mother topless and aproned in "A Baby Sister for Frances" while she's fully dressed in all of the other books? Why does Father ooze excessive compliments about the morning egg dishes and the attractive veal cutlets in "Bread and Jam"? Did Mother and Father argue the night before about how to handle Frances' eating habits? Or over Father's pipe smoking, or that apron? And what happened to Garth Williams?

Most people remember Williams as the illustrator of the "Little House" series and of E.B. White's "Stuart Little" before the film industry ruined Stuart. Why, I wanted to know, is Williams the illustrator of the first Frances title but from then on another Hoban, Lillian, draws the badgers? Was there some sort of rupture? Didn't Williams like Frances? Or did the Hobans want to keep her in the family? Therapists will tell you that they avoid giving out personal information to their clients because it sometimes leads to troublesome fantasies on the part of those clients. Even tiny nuggets of information -- an appointment canceled because of an illness in the therapist's family, say, or a client seeing his shrink in the deli aisle at Safeway -- can get blown way out of proportion. I thought about this idea after I began dissecting the dedication pages in the Frances books. Who are Brom and Esme? Who is Julia? And why do they rate dedications? Why not me, of course, is the obsessive's true question.

It took me some effort to find a copy of the last Frances book, "Egg Thoughts and Other Frances Songs," the only one of the series that's now out of print. Along the way I stumbled across a Web site devoted to the much-published and highly original Russell Hoban, who, it turns out, has written far more books on more far-reaching subjects than I ever imagined. (Think "Turtle Diary," "The Medusa Frequency" and "The Mouse and His Child" among dozens of other titles.) I also discovered, via the Web site, more than I really wanted to know about the real-life history of Frances. It seems that Hoban and his wife, illustrator Lillian, had four children -- that would be Brom, Esme, Julia and also Phoebe. In 1969, the year "A Birthday" and "Best Friends" were published, the Hobans moved to England. There was a divorce. Lillian took the kids back to the States, and Russell stayed behind. I'm not sure if my reading of "Egg Thoughts" would have felt more or less elegiac had I not found the Hoban Web site, but elegiac -- as well as funny and shrewd -- is how it feels.

Which is not to say that it's any sadder a book than the other Frances titles: It's mostly sad because it's the last one. Frances' personality -- her wistfulness, her unmasked desires and her wonder -- is distilled in this context, separated from the developed narrative dilemmas that drive the other stories. With "Egg Thoughts," Hoban seems to be offering fans of Frances a chance to expand her story on their own, since he had closed that door for himself.

It's hard not to love some of Frances' koanlike epiphanies, such as the first line of "Homework": "Homework sits on top of Sunday, squashing Sunday flat." But the song that really gets to me, the one that sums up the whole of childhood, is "Lorna Doone, Last Cookie Song (I Shared It With Gloria)." Who else but Russell Hoban, through the pensive Frances, has thought to immortalize the humble resignation of eating the final, plain cookie, the one left behind after all the good ones have been taken? Set against this nearly ineffable backdrop, Frances makes me wonder if obsession, really, is not much more than our play against time, our struggle against losing something that left, however fleetingly, such a sweet taste in our mouths.

All the sandwich cookies sweet

In their frilly paper neat

They are gone this afternoon,

They have left you, Lorna Doone ...

You are plain and you are square

And your flavor's only fair.

Soon there'll be an empty place

Where we saw your smiling face.

Lorna Doone, Lorna Doone,

You were last but you weren't wasted.

Lorna Doone, Lorna Doone,

We'll remember how you tasted.

Every child knows that you hang on to what makes you feel good. I know that Frances is out there somewhere, and she has graduate degrees and an amiable relationship with her first husband. She and Gloria chat on the phone nearly every week. Her dad still smokes that pipe, his chin, as always, thoughtfully tucked. Frances has a garden like her mother's, abundant with tall waving snapdragons, and she subscribes to Utne Reader. I just know there's always plenty of cake at her house. Mine, too.

Shares