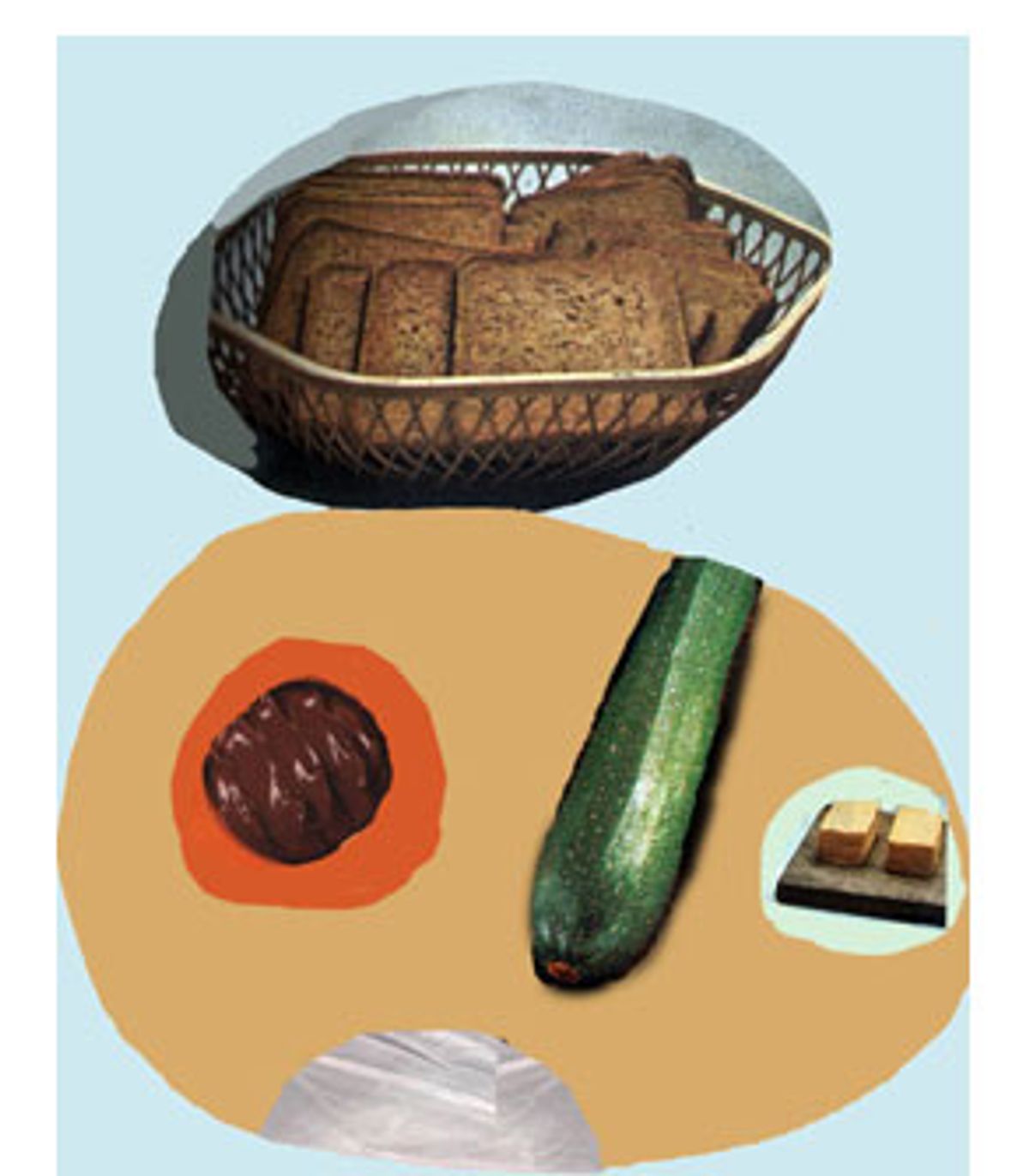

First, the Wesson Oil Ideal Housewife of the 1950s stats for the Famous Chocolate Zucchini Bread: Of all the recipes I've ever invented, this is the one I am asked for most often. The Famous Chocolate Zucchini Bread freezes well, slices thinly, lasts a long time unrefrigerated, is a sneaky way of getting vegetables into children and appeals to the dessert-shy. Production requires no golden hands. It is an excellent way to get rid of excess homegrown or neighbor-donated zucchini, after you have tired of caponata or batter-fried blossoms.

The bread got its start -- as most, though not all, things in my life have -- because of a guy. As part of my squalid (no, make that adventurous) adolescence, I used to slink around the dorms at Cal Tech. One year, one of my playmates from that esteemed institution took me home to meet his parents. I dumped him and kept them -- the surrogate parents I thought I had always deserved. For 25 years, if I needed to run home to mommy and daddy, it was to these folks I scampered. Anyway, one summer, they had the problem of too much zucchini -- so as a small gesture in compensation for their many kindnesses, I devised what came to be known as the Famous Chocolate Zucchini Bread.

The bread really became famous -- this is where the guy angle shines through -- when it became one of the few things I cooked that my (now ex-) husband would actually deign to eat. He was a man of many and considerable charms -- lefty labor lawyer, former hippie cabinetmaker, great dancer, sharp dresser, animal lover, humorous, warm, landed and desirous of offspring. And in my small circle of Berkeley-in-the-'70s hell, he was regarded as the most eligible bachelor in town.

Reader, I married him, as I knew I would when I laid eyes on him at a dance/benefit put on for the antinuclear power Abalone Alliance in my mime/waitressing friends' West Berkeley converted industrial space/studio. (OK, so I was definitely participating in the culture of my time, OK?)

I was so besotted that I didn't remark or object to the fact that he was also a person to whom control was more important than life itself. And as he was also a gourmand and good cook (I knew he liked me when, early on in our courtship, he gave me a bottle of Fox's U-Bet Chocolate Syrup, then unavailable on the West Coast), he had very definite ideas about food.

Part of his slay-me allure was his Old World Yiddishkeit charisma. A native speaker of what he called the "King's Yiddish," he was born in a refugee camp in Bavaria, the only child of concentration camp survivors. Though my low opinion of the work of Marc Chagall has never changed, it was through my ex that I really got what the painter was doing at the emotional level. In the realm of cuisine, his love of the mother country translated into an appreciation of ethnic specialties such as fried noodles and onions. Nevertheless, my yellow warning lights should have gone off that night, early in our relationship, when he stomped out of my flat wordlessly after I served him beef stroganoff, one of my company dishes of the time. How was I supposed to know that the unkosher union of sour cream and marinated steak was anathema -- especially after I had observed him eating BBQ pork ribs at Chinese restaurants?

So it came as no surprise that one of the tipping points that pitched our relationship into the slough of despond came when I baked a fish. Because of my assimilated Southern California extraction and my work experience in Northern California gourmet ghetto cuisine, an experiment with a vaguely Mexican/Asian greenish sauce of tomatillo, garlic, lime and chives seemed to have possibilities.

My husband took one bite and shoved the plate away in disgust. The fish hadn't been prepared in the sweet-and-sour tomatoey/onion mode that he expected, given his Galician heritage, so of course it wasn't edible. That was about the point I just gave up.

Our food fights made the zucchini bread especially precious. It became the one item from my existence previous to our joint existence that met with his approval. He liked it! He liked it! He really, really liked it!

But even the zucchini bread was not enough to save our marriage: Our love -- constituted from equal parts nostril-flaring passion, high drama/high conflict and dark nights during which our two souls each encountered a spirit of equal contradiction and morbid hypersensitivity -- was too exhausting to last for the long haul.

Our doomed love match was as anguished as our bittersweet, Northern California-style divorce was civilized. We didn't squabble over money or property; we acknowledged our love, though we knew we had to part. For several years after we broke up, we had fond phone conversations each week.

But this is where the revenge and remediation part of the story begins: not during the divorce, but when our lives diverged afterwards.

He and I got together when I was in my mid-20s and he in his mid-30s; we split up when I was around 30. In my five-year timeout from the dating wars, the great demographic shift had occurred.

In leaving my marriage, I had become that surplus societal commodity: a single woman over the age of 30. When he and I had hooked up, I had left behind 10 years or so of frolicking fairly freely about; now, reentering the mating marketplace, I found to my horror that every guy was gay, taken, aggressively not interested or aggressively icky. Every social event I went to had at least three semi-interesting single females for every one unattached male. I was entering the next phase of my life, the one that would be characterized by long periods of romantic starvation and high, high, high opportunity costs. Post-divorce, I would end up paying more for my pleasures than I had ever dreamed possible as a boy-crazy teenager, in terms of coping with the elusiveness, unavailability, duplicities and sexual weirditudes/bad manners of my sexual partners.

The narrative arc of the story of our sexual inequality started playing out the day I left Berkeley for Manhattan. On that day, the day that our marriage was officially over, three different women who had been impatiently waiting for me to get out of town asked my ex out. Whereas the first blind date I had when I got to New York took one look at me and walked out the door. From that day on, it only got worse.

It turned out that New York and I were to have a great unrequited love affair: I had always thought the city was fabulous, but the city did not return the favor. Suffice it to say that psychosexual insecurities I hadn't had since junior high school re-erupted with cause.

My new life in the Big City closely resembled Marine Corps boot camp: character-forming, but not much fun. Although I recognized that my ex-husband was not to blame for my post-divorce desuetude, I found this to be very cold comfort on the Saturday nights I spent doing nothing but listening to WNYC-FM and reading Edmund Wilson's fiction and memoirs about his glam, cosmopolitan life in New York.

By the time my ex met his current wife -- six months after we had broken up -- he had had a couple of steady girlfriends. Worse, he met her through friends of mine. Needless to say, there was no such happy symmetry in my life.

I also didn't realize then that the domesticity I so desperately pined for -- the nesting coziness Sam Shepard captured so well in "True West" (coming home in the dusk to the happy shared house, golden lamplight dimly glimpsed through lowered shades, dinner preparations steaming the kitchen windows) -- was not to be my fate. The end of my marriage spelled the end of my third, and most serious, domestic partnership, and I had not yet begun to understand that I was someone who, like it or not, needed to live alone. Dramatic phase shifts such as these are often painful, and accompanied by breakthrough bleeding.

But I hadn't sussed all this at the time, of course. Driven by projection, histrionics, fatal attraction and karma, he and I were symbiotically wedded to each other, whether stormily married or newly divorced. We identified with each other's business in a sibling rivalry kinda way, which was pretty weird, given that we had been lousy at making a family (though we had showed a great talent for recapitulating all kinds of primal scenes from our respective families of origin.)

It irked me to no end that after our breakup, he had it so easy, and I had it so hard. He wasn't forced to do the hard work of post-breakup introspection, not with members of the appropriate sex zooming in at him from all points on the compass to tell him how darling and desirable he was, just the way he was. Meanwhile, I was fuming and desolate, blaming myself and reassessing everything.

So when he told me that, due to his upcoming cohabitation, we would have to stop our comforting post-divorce habit of offering one another emotional aid and assistance and our infrequent (though mutually rewarding) adventures with recreational sex, I became furious. My replacement had definite doormat/biddable girl qualities I could never have. I wasn't likely to be able to find an analog for her of my own -- docile, submissive males are relatively hard to come by, and anyway, I was looking for a companion, not a junior partner or a male equivalent of a broodmare.

In retaliation, I performed the most vindictive, petty, passive-aggressive act I could think of. I baked my ex-husband a batch of his beloved zucchini bread and told him I was mailing it to him as a present for his birthday. What I didn't tell him is that I wrapped it steaming hot out of the oven, with malicious intent. The goal was for the bread to either arrive as an overtly malodorous moldy mess; or as a covertly moldy mess (that is, it would look fine, but the damp, warm, borderline-anaerobic conditions of its cross-country transit would ensure glorious mold cultivation throughout). I sent the bread off with malignant glee.

To folks who are not foodies, this may seem like no big deal. But for the two of us -- who prided ourselves in our craft; to whom friends had said more than once, "Gee, you ought to open a restaurant"; to whom food was love, seduction, currency, power and the highest good -- this was a gesture of poltroonish perfidy. It was the equivalent of spiking a toddler's applesauce with warfarin or adding PCP to the hot apple cider given out at the neighborhood trick-or-treater's way station. I was not so much like the Unabomber as the Lockerbie defendant accused of booby-trapping his pregnant fiancie's luggage: I had defiled our covenant.

Sending the letter food bomb was childish. It was undignified. It marred our track record of generally good post-divorce behavior. He never said anything about it. But I knew what I had done. And since he and I haven't talked to each other in years, I've never had a chance to apologize for such bad form. It's an apology that has been a long time coming.

So.

Sorry, Charlie.

Shares