Flickr/Travdir

If Blockbuster survives, it won't be because of me.

The last time I rented a movie from the ailing video chain was probably about five years ago. And no, I haven't been boycotting out of any high-minded commitment to the mom-and-pop independents that Blockbuster slew by the dozens during its unstoppable expansion in the past two decades. I appreciate local businesses as much as any Salon reader, but what soured me on Blockbuster was something a little less idealistic: Every time I rented something there, I forgot about it, keeping the movie out a day or two too long, which racked up a big bill when I finally did bring it back. The late fees, in the end, were what drove me away. If the chain does stay open, I probably have to pay it $20 from some long-returned DVD before it'll let me take out another movie. (It wasn't just me, either; in 2005, the company had to settle a lawsuit over automatically charging people the full replacement cost of a movie if they kept the discs out for more than a week, and then charging a $1.25 "restocking fee" to anyone who brought back a movie Blockbuster had declared lost.)

On the one hand, at least it had the decency not to send a collection agency after me for its completely arbitrary penalties. On the other, if it's listed all the penny ante debts its former customers theoretically owe it as assets on its balance sheet, its financial state is probably worse than Wall Street realizes.

What's happening to Blockbuster now is, of course, the perfect capstone to its history. The company is trying to restructure more than a quarter-billion dollars in debt and fight off challenges from upstart competitors in a changing industry -- much the way it menaced little players in market after market when its stores oozed out of Dallas to cover the map. (In the Washington area, Blockbuster bought up local VHS rental empire Erol's Video in 1991.) Blockbuster burst out of the Sun Belt and devoured its competitors without pausing, as Wayne Huizenga, the man behind garbage titan Waste Management, used the same overall strategy to push Hollywood's trash as he had used to gobble it up from the rest of the country at his first business. There wasn't a suburban strip mall or a gentrified city neighborhood in America that didn't wind up with a Blockbuster outlet.

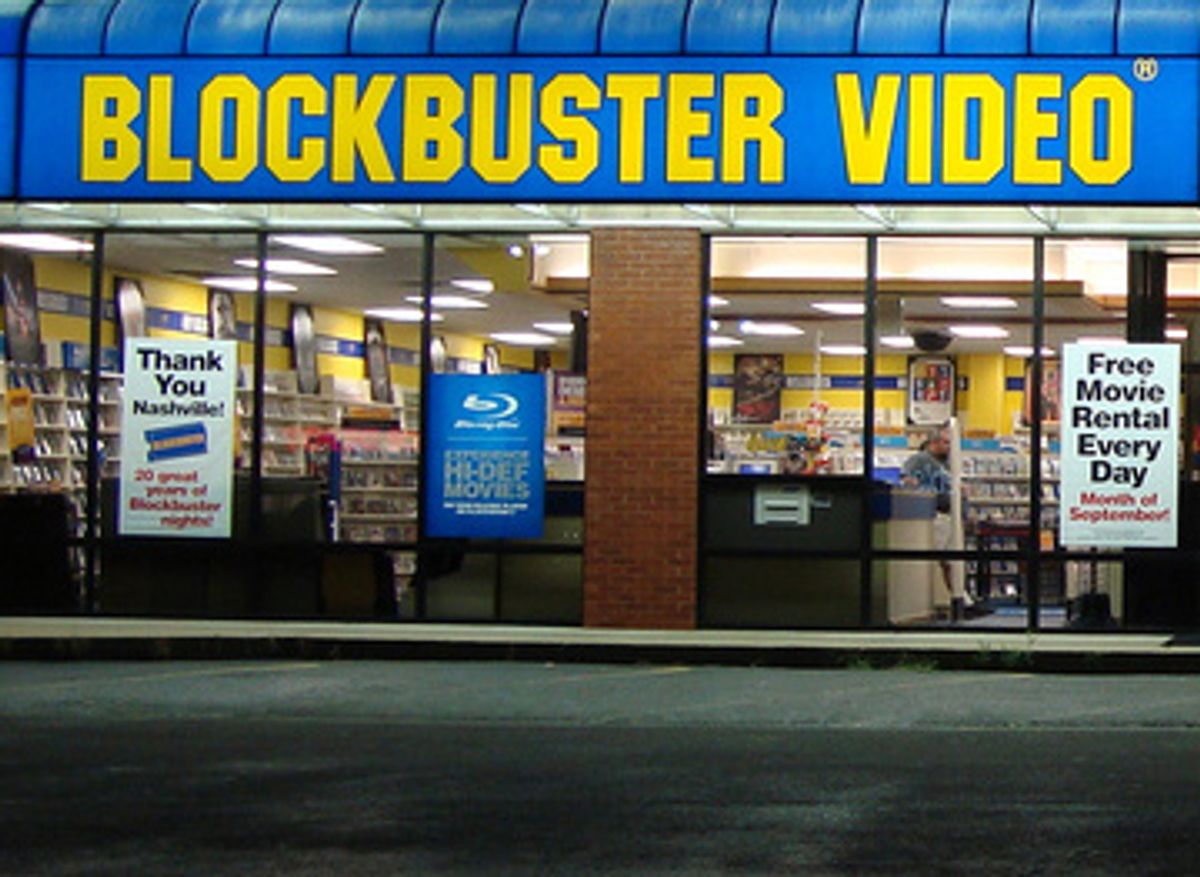

And now that the once-mighty chain's existence is threatened, it's hard to come up with much nostalgia on its behalf. Walking into a Blockbuster, even in its glory days, meant you hadn't managed to come up with anything more exciting to do that night than rent some mainstream Hollywood crap you somehow missed in the theaters. "Make it a Blockbuster night" may have been its marketing slogan, but somehow the vibe in the place made it feel like nothing more than a clever way to say "Admit defeat, loser." Every one of the stores was, and still is, exactly the same: all electric blue and canary yellow, with dizzyingly bright walls, trailers for months-old action flicks playing loudly on overhead TV screens and a few surly employees behind the counter. In a pathetic attempt to be an all-in-one supplier of an entire night's entertainment, the stores throw some popcorn, candy and soda for sale near the checkout line.

Blockbuster presented customers with a binary choice: Breeze through the shelves with a handful of new releases, or scour a sorry back catalog collection for something -- anything -- you hadn't already seen. Home from college in the mid-'90s, I remember wandering through one local Blockbuster (there were three within a 10-minute drive of my parents' house) looking in vain for the third shelf of what turned out to be a two-shelf documentary section. The chain may never have actually censored movies, but its family-friendly public image was so stodgy that no one had trouble imagining it did ("We have heard that for years," a corporate flak told Salon a couple years ago), and its available titles stuck pretty carefully to the less objectionable areas of the MPAA ratings. The chain left the indie and foreign films to the few brave independent stores it hadn't pushed out of business, stocking dozens of copies of the big studios' new releases and purging most movies out of circulation within a year or two. But even if you found something you could settle on renting, it wasn't easy: At least back then, you couldn't check out a movie without having your membership card with you. And the card was slightly bigger than a credit card, so it didn't fit neatly into a wallet.

Still, Blockbuster came to define the very essence of movie rentals. With 7,400 stores around the world, it wasn't hard to see how. One competitor, Hollywood Video, even seems to have copied its color scheme wholesale, as if it's simply impossible to imagine a video store done up in anything other than blue and yellow. Which is why the prospect of a Blockbuster bankruptcy says more about the industry than the company.

Yes, the chain may have been late to realize the threat Netflix posed when the mail-order business started up a few years ago, or, more recently, the threat Redbox's $1-a-night DVD vending machines were becoming. And yes, its stores are run badly enough to have spawned an entire subdivision of the Internet dedicated to bashing the company. But its plight today doesn't seem like a management problem so much as it does the inevitable result of a paradigm shift in the way Americans consume entertainment. The company saw its revenue decline steadily over the last few years, from over $5.7 billion in 2005 to $5.2 billion last year, and it's lost $800 million in the process -- about half of it just in the last year. Meanwhile, Netflix took in $1.3 billion last year, reporting an $83 million profit. A recent report by industry newsletter Adams Media Research predicted brick-and-mortar video stores would only account for 48 percent of all rentals four years from now, as mail-order and Internet business overtakes them.

For Blockbuster now, as for its competitors back in the day, resistance is futile. Except if you clicked on that link, you're actually part of the problem. Why go to a soulless corporate video store when you can watch whole movies instantly on your computer, rent them by mail or order up new releases on demand through your cable company? If Blockbuster goes under, it's hard to imagine the executives at West Coast Video, Suncoast Video or any of the other remaining chains will sleep easily. Meanwhile, the local mom-and-pop store in my neighborhood appears to survive mostly because its pornography section is as large as the rest of the store. But even if that business model means it outlasts Blockbuster, it doesn't seem like a winner in the long run; after all, the only stuff you can find on the Internet more easily than pirated copies of Hollywood movies is free porn.

So whether it's bankruptcy now or bankruptcy soon, it seems safe to say a preemptive "Goodbye, Blockbuster." And no -- I'm not sending you my new address so you can bill me one last time for those late fees.

Shares