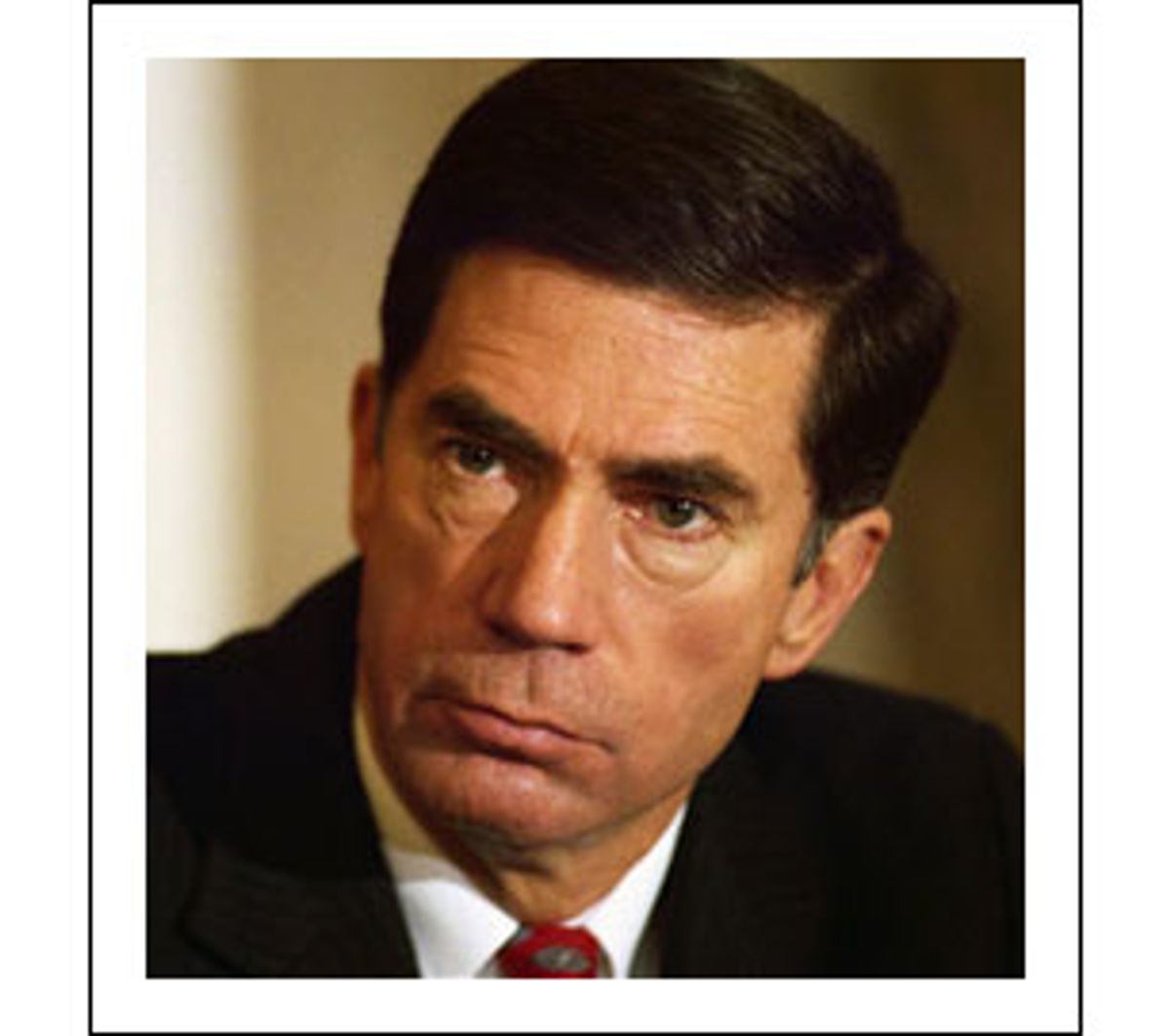

Sen. Chuck Robb, the beleaguered two-term Virginia Democrat, interrupts our interview barely a minute after it begins to take a phone call. It's his youngest daughter, Jenn, who has just been rushed to the hospital with a sports injury.

"She's a senior down at Duke," Robb later explains, admiringly, "and she's the goalie for the field hockey team. She had a shoulder operation over the winter, she's been beat up -- I've watched her -- she's one of those kids

that has grit which is unbelievable. She's broken bones in her fingers, I've seen her knocked out cold, in soccer. She's tough. She makes up for

just average talent with really determined skills. She'll play hurt."

Jenn Robb has since recovered, but she's not the only Robb who knows

something about playing hurt. (Not to mention compensating for "average talent with really determined skills.") Because Chuck Robb -- decorated Marine, son-in-law of LBJ, successful governor, one of the first "New Democrats," a man once thought to be presidential timber -- is by all accounts the most

vulnerable incumbent senator around.

Over at the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Robb's electoral demise is considered the closest to a sure thing that exists in the fickle world of politics. Plenty of others agree.

"I don't think I'd bet on Robb no matter what kind of odds you gave me," says Don Baker, the Washington Post's former Richmond bureau chief.

The vulnerability of an incumbent like Robb could doom the Democrats' chances of taking back the Senate from Republicans in 2000. Currently, the GOP holds a 55-45 edge, and insurgent Democrats need to hold on to all their incumbents, plus pick up open seats -- as in New York -- as well as knock off a vulnerable Republican incumbent or two, to win back the Senate. Robb's likely demise is a disaster for the party's prospects.

There are any number of explanations for why Robb's playing hurt. Since the early '90s, his once-stalwart reputation has been steadily eroded by personal scandals. He was only narrowly reelected last time around, when challenged by the much-scorned Lt. Col. Oliver North. As further evidenced by the midterm elections held earlier this month -- when the Virginia GOP wrested control of the House of Delegates for the first time since Reconstruction -- Virginia is increasingly a Republican state. Robb's voting record does not exactly square with the commonwealth's ever-solidifying conservatism.

Then, of course, there's the man waiting in the wings, itchin' to take down Virginia's one surviving statewide Democrat: the tobacco-chewin',

cowboy-boot-wearin', popular former Gov. George Allen.

"I'm the only one [in the Senate] who has so far drawn a first-tier competitor," Robb acknowledges, "so it becomes a very contested race."

A Mason-Dixon Polling and Research poll from September had Allen beating Robb in a hypothetical match-up, 50 percent to 38 percent. Allen also leads in the money race, $2.5 million to $1 million for Robb, according to June 30 Federal Election Commission filings.

"When's the last time you saw an incumbent this far behind in the polls and this far behind in fund-raising a year out?" asks Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia Center for Government Studies.

(Answer: never.)

There's another deficit between the two men, and that's in personality. Robb is stiff and awkward. Human connection does not come easy for him. His

robotics make Al Gore look like Robin Williams.

Allen, by contrast, comes across as folksy, authentic, "good ol' George,"

as Baker calls him, yet his drawlin' country-boy exterior belies the cunning of a fierce ideologue.

In our interview, I mention Allen's charm factor to Robb.

"And he's been governor more recently, so he has two distinct advantages," Robb replies, affirming his own social shortcomings without my even having

to bring them up.

"I'm not underestimating the challenge at all," Robb continues. "It's going to be very tough. I'm going to have to go through a difficult period when you have to constantly be tagged as 'the most vulnerable,' or whatever it is ... I realize that for the better part of a year it's going to look [like I'm going to lose]. And I'm going to have to just count to 10 and bite my lip when people write me off, or write checks to the other side because they think that's the smart way to do it ... But I've been through that before."

Sabato observes that "Robb's challenge is that he has to make people think

again, because their first thought has already ended his senatorial career."

Back in 1977, when he first ran for lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robb

was a political consultant's wet dream. While other Democrats were (and

still are) hammered for being soft on the military, Robb was the class

honor graduate from Marine Corps Officers Basic School, and had served in

Vietnam -- he commanded an infantry company in combat, earning the Bronze

Star.

Robb also had married into political royalty -- and the fund-raising network

that came with it. As a military social aide at the White House, he had met

and, in 1967, married President Lyndon Johnson's daughter Lynda Bird. Media

coverage was gushing and syrupy, befitting what Robb refers to now as "sort

of a fairy-tale wedding."

And though critics decried Robb as having married his way into politics --

deriding him as "Chuckie Bird" -- LBJ inc. was a lot more help than

hindrance. Former first lady Lady Bird Johnson stumped for her son-in-law,

and LBJ cronies like then-Sens. Lloyd Bentsen, D-Texas, Allen Bible,

D-Nev., former Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas, former Democratic Party

Chairman Robert Strauss and Jack Valenti kicked in with cash.

But Robb wasn't just a favorite of Washington liberals -- he also enjoyed

the assistance of more traditional Southern Democrats, like former Virginia

Gov. William M. Tuck and former Rep. Watkins M. Abbitt. Much of

Robb's success then and in years afterwards lay in his ability to appeal to

both Northern Virginia limousine liberals and the more "Cm'ere, boy"

Dixiecrat-ish types.

His GOP opponent for lieutenant governor taunted, "If my opponent were

married to Lynda Jones or Lynda Smith, would he be here tonight?" But it

didn't much seem to matter. Robb won handily, and was immediately ordained

for bigger and better things.

"There's no doubt he'll run for governor and eight years from now he'll be

a candidate for president. He's going all the way," the Democratic state

Senate majority leader told the Washington Post in 1977.

Four years later, in 1981, Robb easily cruised into the governor's mansion

where by most accounts he did well. "He was a good governor," the Post's Baker says.

"He bought teacher salaries up, he brought Virginia more into the

mid-Atlantic." According to the Almanac of American Politics, Robb was

"given credit for much of Virginia's dynamic growth" during the early '80s."

The seeming inevitability of a President Robb was given more momentum

during the early '80s, when he profiled as a conservative Democrat,

co-founding the Democratic Leadership Council and staking out a pro-growth,

pro-education, anti-tax middle ground.

"I'm not the kind of Democrat [Republicans] used to be able to beat," Robb

says. "They used to be able to beat [former Lt. Gov.] Henry Howell and some of

the others because they could classify them as the typical tax-and-spend,

ultra-liberal, special interest Democrat. Well, I certainly was not in that

category as the governor. I was fiscally responsible. Not only did we not

have any general tax increases, we didn't do any increases in bonded

indebtedness during the period that I was governor. I think the citizens of

Virginia like the idea that a Democrat could be fiscally responsible ... that

a Democrat can be supportive of a strong national

defense, and all the matters that used to be seen as Republican issues."

In 1988, Robb declared his candidacy for an open Senate seat. The GOP

couldn't even get a decent candidate to run against him; the party had to

make do with an obscure Baptist preacher.

"I was always a bit of a problem in terms of [the GOP's] characterizing me

the way they had been able to characterize the 'McGovern Democrats,' or the

'Howell Democrats,' or whatever," Robb says.

"So they expanded into other areas."

Well, someone was expanding into other areas, but blaming said expansion on Republicans seems a tad unfair. After all, you can't serve up a juicy

steak to a pack of dogs and not expect them to eat it.

Robb had been a straight arrow his whole life -- an ROTCer at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, one of the birthplaces of the anti-war

movement; a soldier during Vietnam; a faithful husband and father of three girls.

That changed. In the early '80s, then-Gov. Robb's marriage to Lynda was on the rocks. He reportedly consulted a divorce attorney. At the same time,

Robb was hanging with a fast crowd of real-estate developers, a man named Bruce Thompson foremost among them. Wild girls, wild parties. It was the

'80s, remember.

Many of the subsequent allegations about these wild days and nights had trickled out in the media before Robb was elected to the Senate. In 1987,

Robb's name came up in a federal investigation, led by U.S. Attorney Bob Wiechering, into coke 'n' whore parties in Virginia Beach. The Richmond

Times-Dispatch reported that Robb was believed to be involved.

In August 1988, the Virginian-Pilot/Ledger-Star, of Norfolk ran a front-pager noting that "10 of [Robb's] friends or acquaintances were

among those drawn into a federal cocaine probe now winding down in Norfolk. The 10 businessmen, each of whom resided at the ocean front, have been

convicted, indicted or given immunity from prosecution in exchange for cooperation in the two-year investigation. Robb's ties to some of them were tenuous, but others were often in his company when he visited Virginia Beach."

His Republican opponent in the 1988 Senate election, Maurice Dawkins, seized on the issue, running harsh ads addressing the subject. "Newspapers report Chuck Robb at numerous

parties with open cocaine use," one such ad said. "Robb's friends have been indicted, given immunity for testimony or gone to prison on drug charges ... Bad judgment."

"On Nov. 8, Virginians should just say no," Dawkins said in campaign appearances.

But few voters paid heed. "This 'issue' should be consigned to the garbage heap,"

sniffed the editorial page of the Washington Post.

On Nov. 8, 1988, Virginians just said yes, and Robb trounced Dawkins handily -- 71-29 percent -- the largest vote total for any office in the history of the commonwealth.

But Robb staffers were concerned. As first reported by Regardie's Magazine, in the fall of 1990, Robb staffers David McCloud, Bobby Watson and press secretary Steve Johnson sat down with political consultant Robert Squier. They made two decisions that day that later exploded in their boss's face.

One, they strategized about focusing the media's attention away from Robb and toward the new governor, Doug Wilder, an African-American Democrat with presidential ambitions and with

whom Robb had feuded for the better part of a decade. In 1988, one of Robb's Virginia Beach buddies, Bobby Dunnington, had taped Gov. Wilder on his car phone, gloating about the fact that the nasty stories about Robb were finally making the papers.

"He's finished," Wilder said on the tape,

laughing and bragging that he'd been the source of one of the stories. Robb's political operatives cluelessly believed that the tape was a smoking

gun, calling into question the veracity of all of the Virginia Beach stories, tainting all of the tales as politically motivated.

Squier's second bad decision was to dispatch Team Robb to Virginia Beach to find out what had actually happened with their boss. Had Robb used cocaine? Had he been diddling around? If they were going to be prepared for any forthcoming press inquiries, they had to figure out what had actually happened.

Meanwhile, all stayed quiet for Robb's first two years as a senator ... a little too quiet.

The Washington Post's Baker had been sniffing around, but no bombshells seemed to be forthcoming.

In the Senate, Robb tried to stake out the same moderate ground that had gotten him there, devoting most of his energies to fiscal conservatism and military hawkishness. Robb is one of only two senators honored by inclusion

in the Concord Coalition's deficit reduction honor roll for six years in a row. He is the only senator ever to serve simultaneously on all three

national security committees: Intelligence, Foreign Relations and Armed Services.

Then, suddenly, in April 1991, all of Robb's hard work was undermined when he was surprised by a producer for the NBC-TV show "Exposi" who didn't come a-knockin' with fiscal responsibility on her mind.

Robb was grilled about the use of cocaine at those Virginia Beach parties, about women named Frankie, "the two Tinas" and a former Miss Virginia USA

named Tai Collins. He fumbled, and wasn't able to talk straight. He said that he had seen Collins (whom he had formerly denied even knowing) in his room at New York City's Hotel Pierre, but that all she had given him was a "nude massage."

His staff panicked. In a preemptive strike that quickly backfired, Robb released the two-

before NBC's "Exposi" ran, thus giving other media outlets an excuse to air his dirty laundry to an even larger audience.

"This girl was down on her knees ... doing cocaine right in front of Gov. Robb," a car dealer named Gary Pope told the cameras, describing

one 1983 party.

The media went bananas, of course. "Some journalists said the story was fair game because it conflicts with Robb's carefully cultivated image as a milk-drinking, jut-jawed ex-Marine family man," noted Post media critic

Howard Kurtz at the time. Robb's Democratic rival, then-Gov. Wilder, didn't exactly squelch the rumors. "We have no comment regarding what is being said about Robb's sexual relations and drug involvement," Wilder's press secretary told reporters. There were reports, however, that Wilder had called on the state police to investigate Robb.

Then the taped recording of Wilder on his car phone surfaced. The fact that it had been recorded illegally by Robb's associate Dunnington seemed to offend many more people than Wilder's nasty cackles at Robb's troubles.

From the Robb camp came only more fumbling, more obfuscation, more lies. Robb's staffers -- McCloud, Watson and Johnson -- were put on "paid leave" and hung out to dry. Assistant U.S. Attorney Wiechering reared his head again to investigate. Dunnington eventually pleaded guilty to one count of wiretapping.

By now, Robb had suffered irreparable damage.

Collins soon appeared in Playboy, as "The Woman Senator Charles

Robb Couldn't Resist." Not quite the kind of national media splash Robb had

been hoping for.

Since the rumors had first surfaced, in 1988, Robb staffers had been

pleading with their boss to acknowledge some wrongdoing other than just

lamely copping to being "naive" about his associates, which was all he had

heretofore admitted. Soon it would be reelection time, and something needed to be done.

In March 1994, Robb finally took their advice and sent roughly 450 of his supporters a four-page mea minima culpa. Long before President Clinton was

parsing words and orifices, Robb confessed to actions "not appropriate to a

married man ... I am clearly vulnerable on the question of socializing under circumstances not appropriate for a married man ... For a period of time at Virginia Beach, I let my guard down, and when I did I also let Lynda down. But with Lynda's forgiveness and God's, I put that private chapter behind me many years ago."

Behind the scenes, Baker of the Post had obtained a number of internal memos written by Robb and his former press secretary, Johnson. The 1994 Robb letter to his supporters now gave the Post a news hook on which to hang its cache of the revelatory memos.

The first memo was written by Robb in August 1987 to executives of the Hunton

and Williams law firm, where he had been practicing law and biding his time

until his 1988 Senate run. "I'd have to acknowledge that I have a weakness

for the fairer sex -- and I hope I never get over it," Robb wrote. "But

I've always drawn the line on certain conduct" despite being with "some

pretty alluring company ... I haven't done anything that I regard as

unfaithful to my wife, and she is the only woman I've loved, or slept with,

or had coital relations with in the 20 years we've been married."

The other damaging memo was written by Johnson after Squier had dispatched

Team Robb to Virginia Beach. Johnson wrote, on Dec. 5, 1990:

"Interviews with people familiar with Robb's activities at the beach

indicated that [Robb] allegedly was joined on perhaps two dozen occasions

by people who were heavy drug users and served federal prison sentences on

cocaine and drug-related charges ... Others have alleged that Robb was

sexually involved with at least half-a-dozen women approximately 20-25

years his junior at random times from 1982-1986 ... Robb did engage in sexual

relations, or oral-sex, with at least half-a-dozen women."

Asked about his 1987 memo in an interview with Baker, Robb foreshadowed

Slick Willie a decade later with his own version of Parsing 101: "I choose

my words with care ... I previously said I hadn't slept with anyone,

hadn't had an affair. I clearly did not limit anything more than that. I

drew a line and stuck by that line. And I really don't think it's any of

your business or anyone else's business."

Didn't matter. It was in the papers and on the TV again. All that hard

work, his diligence on national security and team-building with

Republicans as a member of the dwindling Senate Centrist Coalition, now seemed for naught. His name was dragged through the muck once again.

Didn't matter that he and Lynda

had patched things up, that he had devoted

himself to her since those days, and to their three daughters, and to being

the best senator he could. He was still being crucified for things that he

may or may not have done some 10 years earlier.

Joked then-Gov. George Allen, "Virginia is for lovers, but maybe not that

type."

The sleaze was given even more air time when Robb's Republican opponent,

Iran-Contra figure Lt. Col. Ollie North,

aired ads asking, "Why can't Chuck

Robb tell the truth? About the cocaine parties ... or about the beauty

queen in the hotel room in New York?"

"Robb says it was only a massage," the ad sneered.

North led in the polls and in fund-raising, but everyone knew the race would come down to the last few hours. "In 1994, the only person Chuck

could beat was Ollie, and the only person Ollie could beat was Chuck," says Baker.

Lucky for Robb, North had his own baggage. In 1989, he had been found guilty of aiding and abetting an obstruction of Congress and two other

crimes. Though all three convictions were overturned on appeal, moderate Virginia Republicans nonetheless protested his candidacy, urging an independent Republican to run, siphoning off 11 percent of the vote and handing Robb a reelection victory previously considered impossible.

But had his execution been stayed, or merely postponed?

Enter George Allen Jr., whose dad had been the legendary coach of the Washington

Redskins. The senior Allen took the team to the playoffs in his first season as coach, in

1971, and to the Super Bowl the year after that.

At his father's funeral in 1981, Allen Jr. quoted his pop: "To be successful, you need friends," he recalled, "to be very successful, you need enemies."

Allen Jr. has always seemed determined on being very successful. He is as

tough and competitive and merciless as was his father. It's the kind of attitude that wins Super Bowls -- and elections.

Sitting in his office at the Richmond law firm McGuire Woods Booth & Battle these days, Allen can scarcely stay in his seat. He is clearly juiced and ready to take Robb on. He cancels another meeting to keep talking to me -- or at me,

rather.

"This is a good exercise," he tells an aide.

In May, driving home from Shenandoah, Allen ran into a deer. The deer was

killed. "There were no charges against me, just so you know," he jokes. Now, he says,

he's preparing to gun for Robb with the same speed and force with which his new Jeep Durango killed that deer.

"Why be a spectator when you can be a warrior?" he asks.

He's always been pugnacious. In 1976, Allen clerked for a law firm in Alexandria, Va., where legend has Allen expressing disapproval at a

senior partner's willingness to fraternize with prosecutors. It was a battle for him, a war. Not just a job.

Allen began his political career in 1982 as a member of the House of Delegates from Charlottesville, where he had played football for the University of Virginia. Allen's goofy, folksy manner didn't exactly have them thinking of him

as a future governor, much less the man who could someday fell Chuck Robb.

"In the House of Delegates, he was widely perceived as dumb and awkward, a

buffoon," says Baker. "Boy, were we wrong."

In 1991, U.S. Rep. French Slaughter, D-Va., retired, and, in a special election, Allen faced off against Slaughter's cousin, Kay Slaughter, for the seat. It got a little ugly. The National

Republican Congressional Committee ran a TV ad on Allen's behalf featuring Slaughter's image superimposed over a photograph of an anti-war rally with a banner reading, "Victory to Iraq." Allen won with 63 percent of the vote.

But he didn't piss off only Democrats. "I have not come to be a member of a club but rather to fight for the taxpayers of Virginia," Allen told his

colleagues shortly after taking the oath of office. Almost immediately, Allen upheld a campaign promise -- going against the wishes of the GOP leadership -- by voting to overturn the "gag" rule that barred federally funded clinic employees from talking about abortion.

Soon, after his congressional district was eliminated in a redistricting engineered by the Democrat-controlled House of Delegates, Allen suggested that another Republican congressman, Rep. Frank Wolf, move to a new district so he could take over Wolf's old one -- a district where Wolf had lived for a generation.

Wolf demurred.

So instead, after only a few months in the House, the Copenhagen-chawin' Allen decided to run for governor.

No one took him very seriously, at first. "We thought, 'Good ol' George, spittin' his

way to the governor's mansion,'" Baker says. After the respective nomination contests, Allen lagged 40 points behind Democrat Mary Sue Terry

in the polls.

But Allen always plays to win. President Clinton was starting his long slide into disrepute, and Allen campaigned against the "Clinton-Robb-Terry"

style of governance. After the House passed the Clinton economic package and Clinton appeared at a fund-raiser for Terry, Allen said, "Today, as

Democrats nationwide revel in their victory over taxpayers, Mary Sue Terry is sipping wine and nibbling cheese at the Rockefeller mansion in

Washington." Terry, for her part, was running a horrible campaign.

"Clinton is deeply unpopular in Virginia, even among a lot of Democrats," says Sabato of the University of Virginia. "And Allen projects the image of a very friendly, almost populist Republican."

Allen, who was born in Malibu, Calif., overcame his large deficit in the polls and surfed

the first wave of the Republican revolution right into office.

On Nov. 2, 1993, a buoyant Allen declared that "the days of tax-and-spend

liberalism are over in Virginia ... You, the people, know better how to spend

your money than the bureaucrats in Richmond do. We'll also make sure we

have a welfare system that encourages independence rather than dependence.

Workfare rather than welfare. From Day 1, my focus will be on creating

more and better job opportunities for Virginians."

Baker, who got to know Allen at the time,

says he realized the extent to which he'd previously underestimated the young conservative's political gifts. "I did a 180 on him," Baker says.

"He is almost entirely ideological," Baker says. "If you ask him about an

issue he knows nothing about, he'll ask you two or three questions about

it, then he'll put it into his ideological prism, which determines the

outcome of his position. He's able to understand intuitively on which side

of the issue he should come out. When I saw that, I thought, 'This guy is

very Reaganesque.' He's able to explain his position in plain terms ... he'll

'Aw-shucks' his way through the whole thing, and that really comes across

to voters. It's such a contrast with Robb, who studies the issues to death."

"Of course, because George is the way he is, it cuts both ways," Baker says. "He doesn't compromise."

Indeed, the self-described warrior made headlines almost immediately by

violating Virginia's genteel ways at the commonwealth's 1994 Republican

Convention. There he pledged to confront Democrats harshly, "knock(ing) their soft teeth down their whiny throats."

Ouch.

"You have to enjoy competition," Allen says of his infamous remarks. "I had

said, 'And I say this figuratively' ... Maybe I'm a bit too much like my dad.

But we were in a locker room-type situation, we were at the Richmond

Coliseum and I was trying to get folks fired up. It was a political

convention, after all."

"Allen is the kind of politician who is much harsher in both language and

approach," says Sabato. "You're

either 'for him or agin' him,' and that comes across."

Sabato points out that, in contrast with the current Republican governor,

James Gilmore III, Allen provoked strained relations with minority communities, failed to get most of his budget passed and unsuccessfully tried to lead the House of Delegates into GOP hands. Gilmore, though no less conservative, has used a softer style to be much more successful on all three counts.

"Allen's not warm and fuzzy," Sabato says.

Still, the Virginia economy boomed during Allen's gubernatorial reign, mainly in high-tech. As he came into office, Allen's stated goal was

125,000 new jobs; the end result four years later was more that twice that. Motorola began construction on its $3 billion semiconductor plant in Goochland, and others -- IBM-Toshiba, Motorola-Siemens -- and billions of dollars followed. Allen nicknamed his territory "the Silicon Dominion."

Allen made other moves that were popular with voters and perfectly consistent with

what he had promised. He abolished parole, increased penalties for drug

crimes, slashed the welfare roles, led the charge for a parental consent

law for minors seeking abortions. There were skirmishes over education, the

environment and gun laws, but the vast majority of Virginians seemed to side with Allen.

The gun issue, for instance, had little traction in the recent House of Delegates elections, though Allen had staked out a potentially vulnerable position in favor of a law allowing Virginians to carry concealed weapons, even into recreational centers.

"There was all sorts of hollering and screaming that we were going to turn

Virginia into Dodge City," Allen says. "But the reality is that no one who

received a [concealed-carry] permit has committed a crime with a gun."

(That's not quite right. In February 1996, Robert Asbury -- a January 1996 CCW permit holder -- died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head after killing his estranged wife, Susan M. Asbury, with a

gun.)

As for the environment, where Allen's record is less than exemplary, he

says that Democrats attack him on the issue because they have nothing else

to say. "We've had such success on economic development -- gosh, it's been

unprecedented -- they have to say, 'Oh, well, the way you've done this is

by ignoring environmental laws.' But that's absolutely false. Democrats can

grouse and mew and whine all they want, but it's absolutely false."

Democrats plan on taking rhetorical salvos like this and using them to paint Allen as an extremist.

"He's got that pleasing exterior -- the cowboy boots and the tobacco --

which does a lot to soften the edges of a pretty frightening ideology,"

says Jim Jordan, political director of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign

Committee. "Upon reexamination it's going to hurt him."

"His weakness is education," assesses Sabato, who attended the University of Virginia with Allen. Democrats will point to Allen's proposed budget cuts for K-12 -- student-health programs, at-risk youth programming, English as a second language -- as well as his desire to eliminate a college-aid program for minority and low-income high school kids. They'll remind voters that Allen was the only governor in the country to refuse Goals 2000's federal money because he didn't want the federal government to have any say in Virginia education. ("It was a pittance of a flea on a hair of a dog wagging the whole dog," Allen says.)

Most significantly, Allen's Christian Coalition-backed revisions of the commonwealth's "Standards of Learning," or SOLs -- which included adding Bible studies and changing the terminology of African slaves to "settlers" -- found adamant opposition in the Northern Virginia suburbs. "His positions on SOLs were enormously unpopular," says Sabato.

But it's unclear how resonant that issue will seem to the electorate in its entirety. Votes will come in from the whole commonwealth -- Norton and Bristol, Salem and Roanoke, Lynchburg and Appomattox -- not just the northernmost area closest to D.C., which is dismissed by the rest of the commonwealth as "The People's Republic of Alexandria."

No question Allen is a tough S.O.B., but he also left office with approval

ratings around 60 percent. Sabato points out that Allen's popularity tops

out in that he failed to win control of the General Assembly in 1995 by "coming

on too strong" and "making it a statewide referendum on him." And the 60

percent approval rating might be a decent showing compared with other

governors from other states, but in Virginia it's "quite low."

Allen's vulnerability, therefore, is underestimated, Sabato insists, but "it's just that

Robb is the walking wounded."

Ironically, Robb says that the very scandals that nearly spelled his doom in '94 have freed him to take positions that may help spell his doom in 2000.

"Sometimes it's like being in a crucible," he says of his toughest political days. "But you get put through the fire and you realize what's important." For Robb, that has led him to emerge as one of the most outspoken senators in the country on an issue far from near-and-dear to the hearts of his voters: gay and lesbian rights.

Robb was the only Southern senator to vote against the "Defense of Marriage Act," a warning shot against the recognition of gay and lesbian unions. He opposed "Don't ask, don't tell," and he's repeatedly appeared at fund-raising galas for the Human Rights Campaign.

"On social issues, he's turned quite liberal," Sabato says. "Gay rights are not too popular in Virginia. Not even really in Northern Virginia. And in Southern Virginia [such a stand] is deadly."

Robb denies that he's "suddenly turned into a huge bleeding-heart," though he adds that he "sees there's discrimination that's taking place, and it's race and it's orientation and it's gender." The issues never came up when he was governor, he insists. "I've always been on the progressive side of rights and social issue ... I think the majority of Virginians are there, too." He acknowledges, however, that "the positions that I've taken on some of these high-profile issues are very easy to misrepresent or demagogue, so it'll be a real challenge."

Robb says that he's seen a lot of discrimination, and has opposed it his whole life, though he only recently has begun standing up against it. As a young Virginian attending Mount Vernon High School, his school bus would drive through a black ghetto "and that bothered me then," he says. "But I was in high school." Subsequently, as an ROTCer, and a soldier, and a 'Nam vet, he sat out the civil rights movement.

As a clerk with the judge advocate's office, Robb was given responsibility for officer qualification records of all Marine officers in any disciplinary hot water for any reason. His files "included a couple cases where an officer was suspected of being gay." It didn't matter "that they had combat records that were superb ... the conventional wisdom, which I nominally accepted -- I didn't advocate it, but I accepted it -- was if you're gay and you're in the military, you present a potential security risk, you can be blackmailed. We later learned that there was never -- apparently anywhere in military history -- where they found a case when anybody was actually blackmailed for sensitive national security information.

"I thought there's something fundamentally wrong" with the policy, he says. "If somebody -- whatever their own orientation may be -- if they have an outstanding record, if they perform in a way that was outstanding in combat, I mean, it was very clear to me that their careers were over. They didn't know it at the time. I'm not sure that they knew then that the derogatory information had been put in their record, and that at some point they were going to be discharged and it may have been under conditions other than honorable. If you say, 'We're going to keep you from serving your country if you are something that we disapprove of,' I mean, this isn't conduct, it's status. I don't follow that. As Barry Goldwater said, 'I don't care if they are straight, I just care of they can shoot straight.'"

I pointed out to Robb that such a position might not resonate with Virginians next year.

"It's exactly the things where I'm going to be called on the carpet that I think I have a mission," he says. "I get more satisfaction from government service since I've been doing that more vocally. I wasn't voting 'wrong' when the issues came up before, but I feel much better about myself" since taking these stands. "I will come home, and I will be pumped up ... I feel like I'm more valuable if I'm willing to stand up for what I truly believe in ... and I can make up for passing through the area that I used to drive through. Or because I was a Marine Corps officer and I saw ... discrimination adversely affecting the careers of people who served with distinction."

The majority of voters might not appreciate his stand, and he knows that. But there are moments when young men and women come up to him and thank him for speaking out on gay and lesbian rights. "When someone comes up to me, it's a very human connection. I'll know that I've touched that young man's life. And I didn't even know what kind of burden he was carrying. Frequently young men or women come up to me and thank me in ways that you couldn't begin to pay me for. There are worse things to work for."

"I get satisfaction when I stand up for something that's unpopular but I know it's right," Robb says. "And I know eventually history will demonstrate that I was on the right side -- even if I may have been politically ahead of my time."

Sabato says that Robb's near-death experience (politically speaking) in '94 has led him to boldness. "I think he has suspected all along that this may be his swan song," Sabato says. "He's never admitted it publicly, and he'll certainly give it his best shot next year, but at some level of his subconscious I suspect that he thinks that this may be his swan song. And he's tried to vote in a way that will make him and his children and his grandchildren proud. I know it sounds corny."

Robb insists that he will win. He has a sense of timing, he says, and he will come on strong after Labor Day and will emerge victorious. But there's a sadness in his voice, a resignation. Several times during our interview he starts to tear up. His voice cracks and his eyes well with tears when talking about his family and how they've stuck by him, how his running for reelection is "selfish" in a way. "And they say I have no emotion," he says.

The other time he chokes up is when he tells me about his father-in-law, President Johnson, and how after a major heart attack LBJ disobeyed doctors' orders to be with members of Texas' Mexican-American community who had just lost children in a bus accident.

"There was a time when I needed their parents, and they were there for me," LBJ said. "And they need me now."

"Three weeks later he died," Robb says. "That's when I knew about commitment. That's when you knew a lot of things taken as politics, if they really reach down into somebody, they can mean something. I married his daughter; I fought in his war. But it wasn't until then that I really understood what motivates some people to public service."

Sen. Robb wants me to emphasize that he doesn't think he will lose. He thinks he will win.

But, Robb adds, "I would be quite content to lose for the right reasons if that's to be the case."

Shares