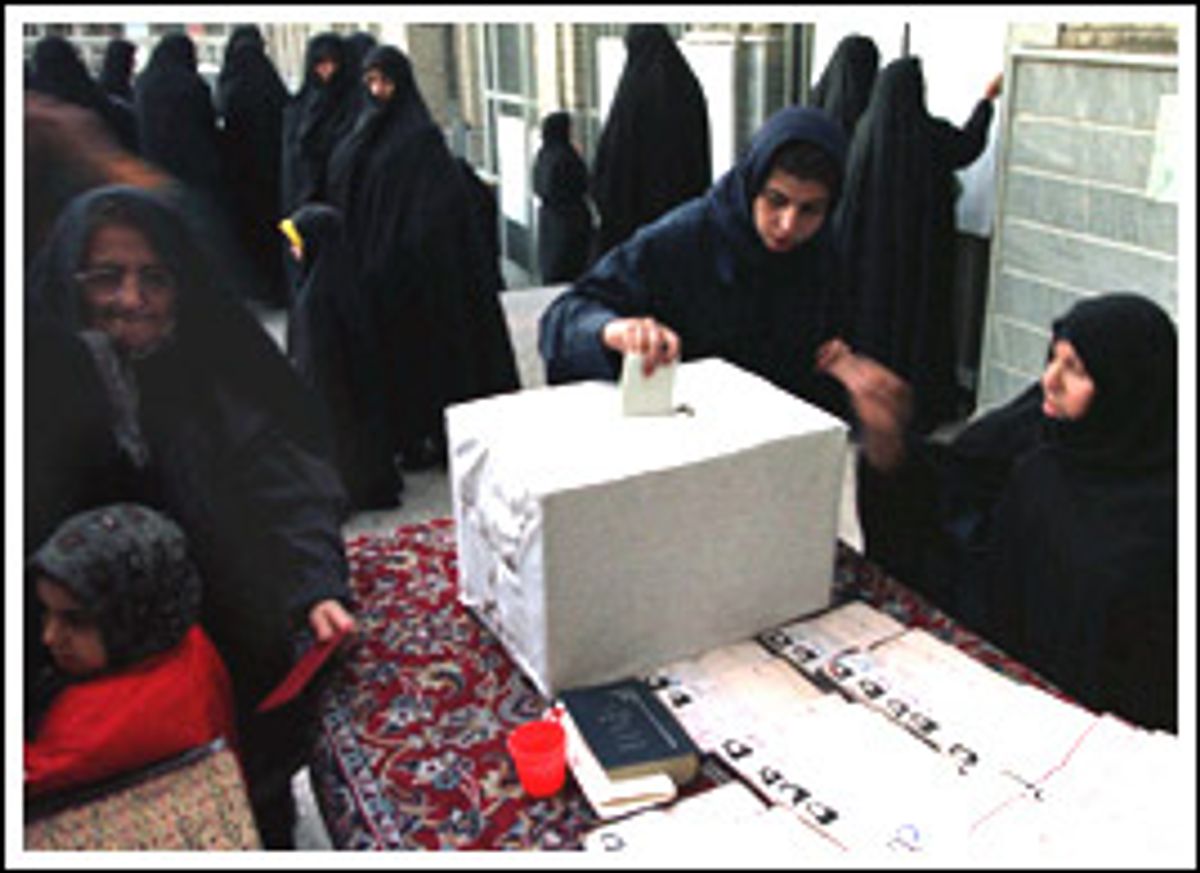

The power of Iran's dissident press has produced tangible results by helping to rid the country's parliament of the bulk of its conservative members in Friday's elections. Early results suggest reformers will control more than 70 percent of the new parliament, due to convene in May.

Many of the newly elected reformers are journalists, directors of banned dailies or advocates of the freedom of the press. The No. 2 vote-getter in Tehran is a woman journalist. And one of the highest items on the reformers' agenda is amending a restrictive 1984 press law.

Every day, Nik-Ahang Kowsar, 30, reads Iran's press in search of subjects for his satire and pens three cartoons mocking conservative politicians. "That's three different cartoons attacking them every day," said Kowsar. The cartoonist remains undaunted by a weeklong spell in prison earlier this month.

Journalists in Iran are forbidden from criticizing religious leaders. Koswar can draw secular politicians but no one wearing a clerical outfit -- a severe limitation in a country ruled by clerics. "We know we can't write about religion and we accept it -- we don't draw clerics," said Kowsar.

But when Kowsar drew a crocodile shedding tears on the freedom of the press, young theology students thought he was mocking a Tehran clergyman whose name rhymes with the Persian word for crocodile. The students rioted for several days, demanding Kowsar's head and the cultural minister's resignation. Kowsar claims he was attacking the conservatives in general, not a specific clergyman. "I wouldn't attack a person," he said. "Criticizing the idea is more important."

Koswar believes in the power of the pen. "It's something between having a mission and craziness," he said.

Crazy or not, repeated attacks on conservative politicians by Kowsar and other journalists in Iranian newspapers is proving to have a profound impact on the nation's democratic government.

The Iranian press, which was anemic not long ago, owes its new vitality and political clout to the more tolerant atmosphere that followed the election of a liberal-minded president, Mohammed Khatami, in May 1997. Although television and radio broadcasting fall under the authority of Iran's spiritual leader and have remained in the hands of conservative clerics, anti-establishment newspapers have managed to blossom in the past few years.

The press has become one of the main battlegrounds in the struggle between Iran's conservatives and reformers. The judiciary, controlled by hard-liners, has tried to shut up as many newspapers and journalists as possible, but has found itself outpaced by the growing number of people willing to take risks for political change.

"We were used to writing with our bags packed, ready to be taken to jail," said Ebrahim Nabavi, author of a widely read satirical column in the pro-Khatami newspaper the Age of Freemen. "There used to be only one liberal newspaper," said Nabavi, who was put in solitary confinement for a month last year when the press court found him guilty of endangering national security with his writing. "But now there are more than 10 and I don't feel as threatened as before," he said.

Journalists have started tackling subjects they wouldn't have dared approach a few years ago. They wrote extensively about the serial killing of dissidents by rogue intelligence officers in December 1998, and shed light on the disreputable role played in the affair by Hashemi Rafsanjani, Iran's former president and a long-time politician.

Rafsanjani's popularity plunged as a result of the media campaign launched against him. "Fifty percent of Rafsanjani's votes were taken away thanks to the activity of the press," said Nabavi. "Even if he was the third most important political figure in the country, we had the power to knock him down."

Once expected to be the next speaker of parliament, Rafsanjani scored poorly in last week's election and probably will not secure a seat in parliament until the elections' second round.

As the press has become more influential in shaping public opinion, the demand for caustic political commentary has also increased. Iranian readers used to be content with mild cultural cartoons such as those published in Mr Flower's, a moderate satirical weekly founded in 1991. But the weekly has been losing readers in the past few years, especially among the young.

"People have become obsessed with politics," said Nabavi, who said he would rather write about cinema. "Before Khatami's election, people didn't have the space to express their democratic ideas," he said. "Since then people decided to become more active in politics -- the result is this new democracy."

Analysts hope the newly elected reformist parliament will help secure these gains in press freedom. Many of the limitations affecting journalism were never written down and are subject to change. But journalistic freedom will depend on reforming the country's court system. "If parliamentarians can change the laws regarding the judiciary, then change could occur," said Kowsar.

However, laws passed by the parliament must be approved by the Council of Guardians, an official but non-elected decision-making body composed of 12 clerical Islamic scholars.

Despite jubilation among reform advocates over the election results, some think the pro-Khatami coalition, which secured an overwhelming majority, will disintegrate into factional politics. "The conservatives are defeated, but they will form a very strong opposition minority, while reformers will be divided into factions, " said Kioumars Saberi, 59, managing director of Mr Flower's. Pulling a dusty copy of the 1984 press law out of his desk drawer, he predicted, "I'll show you the same press law next time you come."

Shares