It's hard to say how many more official probes it will take before Jesse Jackson and black leaders accept the bitter truth that black Mississippi teen Raynard Johnson was not lynched but committed suicide. The latest to come to that conclusion is Michael Baden. The world-renowned forensic expert visited Johnson's home and thoroughly reviewed two autopsy reports, one of which was privately commissioned by Johnson's family. He found no solid evidence that Johnson was the victim of racist violence.

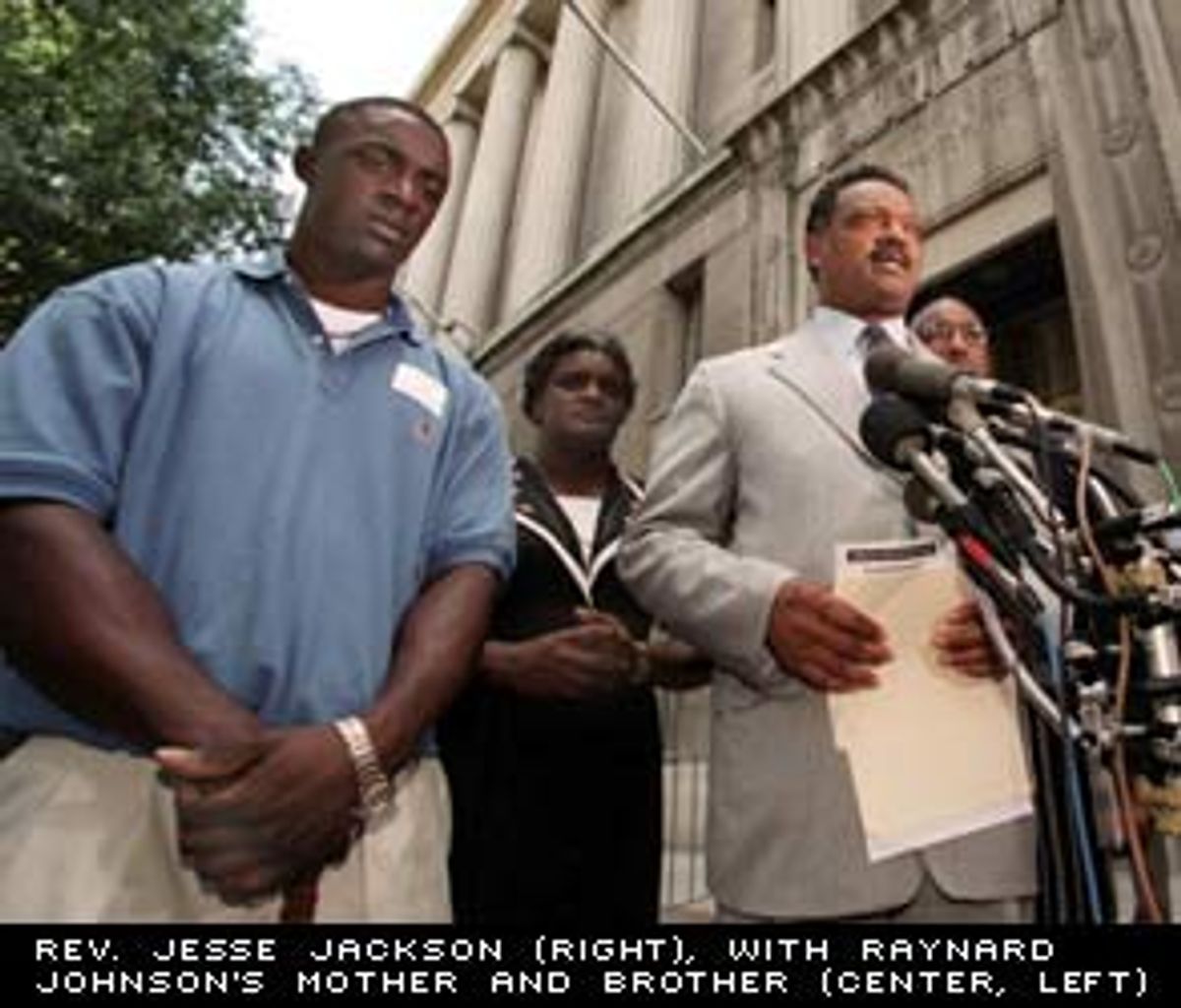

Baden's findings were made public by the commander of the Mississippi Highway Patrol, an African-American. But even this probably isn't enough to persuade Jackson and other black leaders that white racists didn't murder Johnson. Not surprisingly, when Jackson was told of the latest conclusion, he did not return phone calls from reporters for comment. Hopefully, Mississippi's governor won't hold his breath waiting for Jackson and other black leaders to heed his call to apologize for smearing the state.

It's easy for Jackson to fuel the flames of racial paranoia about Johnson's death. Thanks to the civil rights meltdown, assaults on affirmative action, racial profiling, the wave of police shootings in black communities, the grim economic plight of many young black males, the grotesque disparities in the prison and criminal justice system, more and more blacks are convinced that terrible atrocities are being planned for them.

That was painfully evident to me recently when I spoke to a large group of African-Americans. During the question and answer period, the issue of the burning of black churches came up. I pointed out that nearly one-third of the more than 100 people arrested by FBI and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms agents in the burning of over 200 churches were black. In some cases there was strong evidence of a loose conspiracy by a disjointed group of racist whites to burn these churches. But this should not let the blacks that burned their own churches off the hook.

There was nothing racial about their motives. They burned their churches out of revenge, anger, to conceal thefts, or to perpetuate insurance fraud. They were criminals and no one should try to excuse or justify their shameful acts. Disappointingly, several blacks did. Angry, they immediately shouted, "How do we know that they actually burned the churches? The only thing we have to go by is the white man's word." Their blindness to reality was the ultimate in collective racial denial.

Time and again when an African-American winds up in front of a court bench, more than a few blacks will shout that he or she is the victim of a racist conspiracy. It is a good, if not well-worn, ploy that some black personalities have raised to a state-of-the-art enterprise when they are accused of, or nailed for, sexual hijinks, bribery, corruption, drug dealing and possibly even murder.

Here are some tragic examples of this. The Rev. Henry Lyons, president of the National Baptist Convention USA, the country's biggest and most influential black religious organization, was convicted of racketeering and grand theft in 1999. The evidence was overwhelming that Lyons was a crook. Yet even after Lyons admitted his guilt many black ministers still wailed that he was the victim of a white conspiracy.

Despite a mountain of lawsuits, countless threats of government prosecution and numerous allegations of unsavory dealings by boxing promoter Don King, NAACP officials publicly rushed to his defense. They hinted that King was a victim of a government plot to destroy him.

Before the first juror has been seated and a single piece of evidence presented to determine his guilt or innocence, supporters of Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown), currently awaiting trial on charges of gunning down two Atlanta police officers, did the same. They relentlessly claim that the charges are part of a 30-year vendetta by law enforcement agencies to destroy him for his Black Panther past.

Since the 1960s, many blacks have pumped the idea that everything that happens to African-Americans -- whether it's the suicide of Raynard Johnson or the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. -- is part of a secret plan to annihilate their race. Their theory goes like this: Following the urban uprisings of the 1960s, the ghettos were flooded with drugs, alcohol, gangs and guns. During the 1980s, AIDS was imported. The "white establishment" wanted to stop blacks from developing unity, strong political organizations and programs to counter oppression. The plot was to get blacks to self-destruct.

There is no hard evidence that any of this is true. And there exists a legion of telltale signs that many blacks reflexively scream racism to cover their misdeeds. The problem is that the victims of those misdeeds are almost always other African-Americans.

Even more damaging, when Jackson and other black leaders claim racial plots, as in Johnson's death, with little or no evidence to back them up, they lay themselves wide open to the charge that black leaders are more interested in playing racial one-upmanship than in promoting racial harmony and achieving tangible racial gains. This is just the kind of charge that gives them -- and the people they supposedly serve -- a black eye.

Shares