While NATO bombs were falling and Yugoslav army troops, Serbian police and paramilitaries were expelling hundreds of thousands of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo last year, Natasa Kandic drove from the Serbian capital Belgrade into Kosovo in her organization's private car. She was on another mission, to get the ethnic Albanian staff of her human rights organization out to safety.

In a country where seemingly everything is deeply, illogically political -- from the soccer team one supports to whether one blames unusually hot weather on NATO -- nothing is more political than ethnic issues.

But Kandic rejects the hatreds that have accompanied the break-up and ethnic conflict in Yugoslavia. In 1992, when Serbs, Croats and Muslims were massacring each other in Bosnia and Croatia, Kandic co-founded a human rights organization in the Serbian capital to champion the idea of human rights for people of all ethnic groups, and the idea that the law should be above politics. Then, as now, that idea is unusual here.

Kandic (pronounced KAN-ditch) has faced Serbian police, ethnic Albanian Kosovo Liberation Army soldiers, Yugoslav army commanders, NATO bombs and regime-controlled judges in her quest to document Yugoslavia's human rights situation. She provides legal defense for ethnic Albanian and Serbian political prisoners, and urges improvements in a country where most people have long been resigned to the rights abuses and war as a matter of course.

Kosovar Albanian villagers crowd around the petite Serbian activist when she visits Kosovo to tell her about rights abuses committed by both Serbs and Albanians. Lawyers from her group, the Humanitarian Law Foundation, have defended some of the more than 1,000 ethnic Albanian political prisoners held in Serbian jails.

Only a few months after NATO bombed Serbia in defense of Kosovar Albanians, Kandic dined at an outdoor Belgrade restaurant with Kosovar Albanian lawyers, which her group had hired to defend Albanian political prisoners in Serbian jails. The lunch would not be unusual were it nor for the fact that many Albanians now refuse to speak in the Serbian language anymore since the war in Kosovo, and most Serbs would not want to be seen speaking with a Kosovar Albanian, a group widely perceived here as responsible for the separatist uprising that triggered NATO bombing. Kandic acted as if the professional interaction were the most normal thing in the world, and the waiters took her lead (and they do again and again).

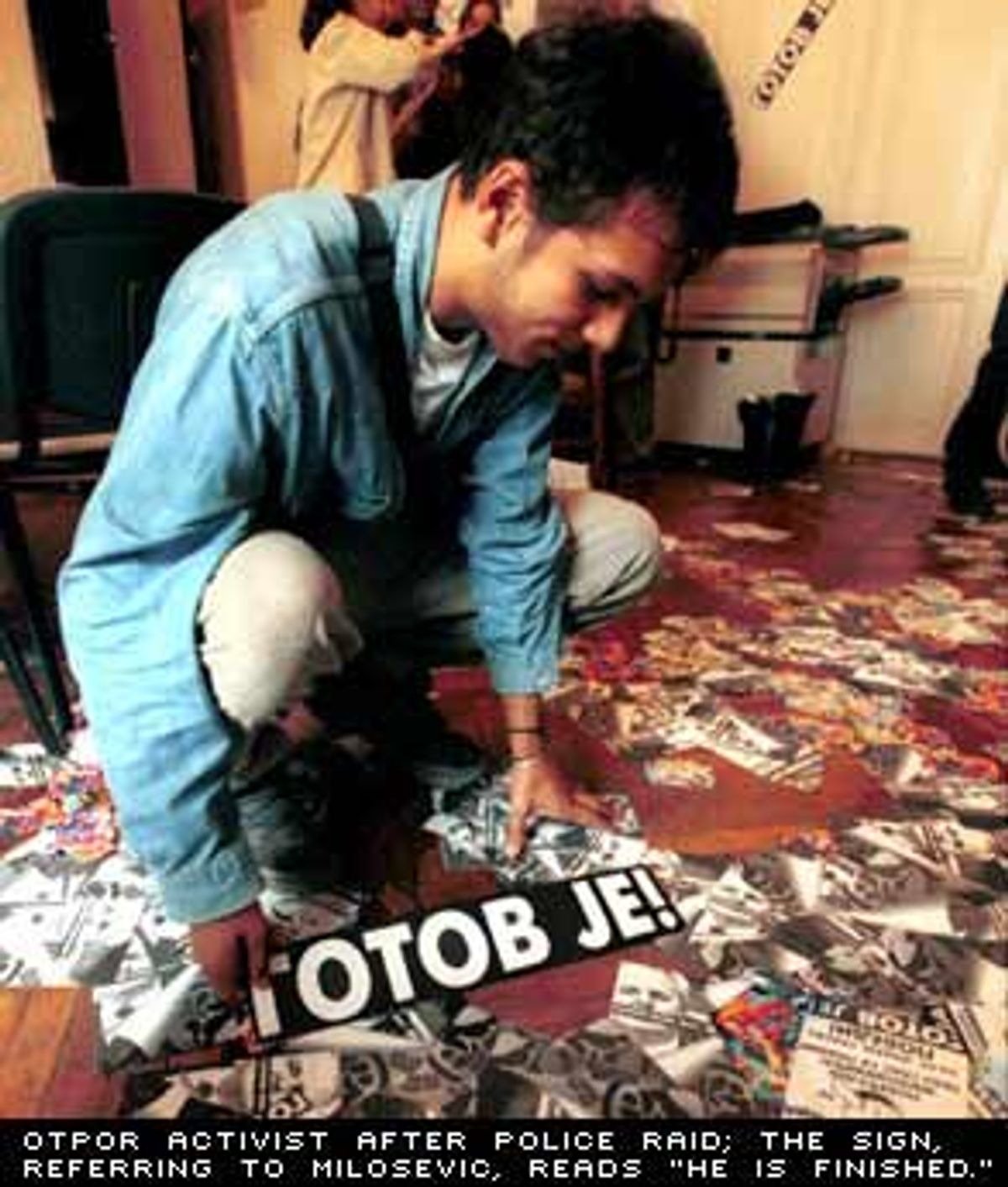

Serbia's persecuted pro-democracy activists rely on her as well. Their headquarters recently raided by Belgrade police, Serbia's student pro-democracy group Otpor (Serbian for "resistance") now crowd her organization's offices seeking legal advice.

Now, three weeks before the Yugoslav elections, Kandic is in need of legal protection herself. Last week the Yugoslav army announced it will sue her for statements she has made alleging it carried out crimes against civilians in Kosovo.

"Kandic has publicly attacked the Yugoslav army as an institution," Yugoslav Army spokesman Svetozar Radisic told a news conference last Friday. Radisic says Kandic's reports "denigrate the army and the state, the Yugoslav judicial system, and cover up the crimes of the Shiptar (a derogatory term for Albanians) terrorists and NATO criminals. Her allegations are so unfounded that no comment is necessary. We consider that Kandic has no arguments and that she should be sentenced for what she is doing."

What Kandic is doing that so annoys Belgrade's army brass is to talk about what she witnessed in Kosovo.

"I will not keep silent about the horror you generals arranged for young conscripts in Kosovo," Kandic wrote in the independent Belgrade newspaper "Danas" the day the army announced its suit against her. "I will also not keep silent about the atrocities committed against civilians, which I saw in Kosovo. I saw Albanian villages encircled by tanks with my own eyes. I heard grenades and saw thousands and thousands of people leaving their homes with plastic bags in their hands, escorted by the police or army, because they were told that Kosovo was not their homeland. I met columns of civilians on the roads."

Kandic's comments in the paper were in defense of another Serb, journalist Miroslav Filipovic, who has reported on Yugoslav army activities during the Kosovo war. Last month, a Yugoslav military court in Nis sentenced Filipovic to seven years in prison on charges of "espionage" and dissemination of false information. Those charges arose from articles he published in the international press citing Yugoslav army documents that showed some army conscripts were suffering psychological trauma because of atrocities they witnessed fellow troops commit in Kosovo -- a kind of Yugoslav version of Vietnam syndrome.

Kandic told the newspaper Danas that Filipovic was charged because he was the "first person to raise the issue of the responsibility of the Army, the Serbian forces" in Kosovo.

The timing of Belgrade's attacks against Kandic and Filipovic is no coincidence. Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic has mounted repression against his critics in the run-up to elections he has called for September 24. Serbian police have arrested more than 1,200 opposition supporters, journalists and members of the student group Otpor in the past four months. Earlier this summer, police took over Belgrade's only independent television station, Studio B, and declared Otpor a terrorist organization. Shortly thereafter Serbian police interrogated the leaders of an anti-war feminist group, Women in Black, and arrested and tortured one member, Bojan Aleksov, who was helping Serbian conscientious objectors flee conscription. Aleksov escaped to Germany, where his case has been taken up by Amnesty International.

In August, Serbian police raided the offices of a Belgrade cultural center called the Center for Cultural Decontamination, seizing the group's computers and office equipment. Financial police have also been busy raiding Serbia's non-governmental organizations. And last week, Milosevic's political godfather turned dissident, former Serbian president Ivan Stambolic, went missing while on a morning jog and has not been heard from since. He is widely believed to have been kidnapped by Milosevic's state security organization.

But even in this atmosphere of selective but growing repression, the cases against Kandic and Filipovic seem unique, as they reveal an effort by the Milosevic regime to silence specifically those who say the Yugoslav army committed war crimes in Kosovo. Those allegations are universally denied by Serbian state-controlled media, which instead portray Serbs as the exclusive victims of the international community, the NATO bombing and ethnic Albanian terrorists in Kosovo.

Bogdan Ivanisevic, a Serbia researcher with Human Rights Watch, says the regime's attacks against Filipovic and Kandic seem targeted for domestic political consumption in the run-up to elections.

"The simple answer is that this has to do with elections," Ivanisevic said in a telephone interview from New York. "Since the end of the war in Kosovo, the intensification of regime repression has been gradual. First, the regime accused people like Kandic of simple lack of patriotism. But recently, the accusations have become more drastic. The regime is accusing Kandic and the student group Otpor of espionage, even terrorism. And needless to say, all of these accusations are blatantly false and absurd."

The reason Milosevic is stepping up attacks against his critics may be a familiar one: to paint himself as the sole protector of Serbian interests, defending the nation against an international community that has unfairly accused Serbs of war crimes. (Indeed, a U.N. tribunal last year indicted Milosevic and four top deputies of war crimes in Kosovo).

Critics such as Filipovic and Kandic give credence to what many Serbs suspect, but don't see on Serb television -- that Milosevic's wartime policies have led to Serbia's international isolation, sanctions, and poverty. If the public heard allegations of war crimes not from the international community, but from fellow Serbs, they might be inclined to vote for someone else.

Last week Human Rights Watch called on the Yugoslav army to investigate allegations its troops commit atrocities in Kosovo, offering "to provide any genuine investigative body with its overwhelming evidence of war crimes in Kosovo." For her part, Kandic too has said she is willing to turn over evidence her group has collected of Yugoslav army crimes in Kosovo.

Yugoslav army spokesman Radisic declined the offer. "A person who puts forth such allegations might be a psychiatric case."

Shares