In less than two weeks, 20-year-old Jonathan Ben-Artzi will likely become the first Israeli conscientious objector in three decades to be tried before a military tribunal, where he could be sentenced to up to three years in prison for refusing to serve in the military. He's already been locked up for nearly eight months without a trial. His family is firmly behind him, arguing that the government is getting tough on so-called refuseniks because they challenge not just Israeli policy in the occupied territories, but the entire structure of Israeli society, built as it is around compulsory military service.

Well, maybe not his whole family. Ben-Artzi's parents are committed Israeli progressives, but his uncle is none other than the ultra-hawkish former prime minister and current finance minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a man to the right of Ariel Sharon. Ben-Artzi's connection to Netanyahu has made his story big news throughout Europe and the Middle East. Though Netanyahu hasn't involved himself in the case, Ben-Artzi's sister, Ruth, a 31-year-old doctoral student at Columbia, believes that the publicity about his famous nephew has spurred the Israel Defense Forces to try first to cajole and then to force Ben-Artzi into line. The head of IDF personnel has even been put in charge of dealing with Netanyahu's outspoken nephew.

"It's either embarrassing the army or putting them in a position where they feel they have to set some kind of example or scare other young men," Ruth Ben-Artzi says. Army spokespeople couldn't be reached for comment.

Meanwhile, Ben-Artzi, a longtime pacifist whose family and friends call him Yoni, isn't backing down. Instead, he, his family and his attorney hope his trial will force a public debate on conscientious objection, a deeply taboo subject in a country where the army is held sacred. "This trial is very important for the force of conscience in the Israeli legal system," says Michael Sfard, Ben-Artzi's lawyer. "If we win this trial it means the Israeli legal system has allowed respect to the human conscience."

Since he's been in prison, Ben-Artzi's family says, a series of high-ranking officers have told him that if he'd simply let himself be drafted, he'll be stationed in a hospital and won't have to fight. But Matania Ben-Artzi, Jonathan's father (and Netanyahu's brother-in-law), says his son refused. "He told them the following," says the obviously proud father, himself a military veteran. "Whatever organization I'm going to join, I'll try to do the maximum in that organization, not the minimum. I am a pacifist. I don't want to join this organization. It does not act in my name. It's morally weak for me to be in the organization and yet to avoid doing what others are doing."

Ben-Artzi was also offered the opportunity to see a military psychologist who could declare him mentally unfit, but again he refused. "I'm not mentally ill," his sister quotes him as saying. "I'm a pacifist. That's not a mental illness. Don't tell me to go to a psychologist who will sign a letter so it will give you a way out so you don't have to deal with me."

Right now Israel isn't sure how to deal with men like Ben-Artzi. Israeli law allows most Arabs, ultra-Orthodox Jews, and females who declare themselves pacifists to be exempted from military service, but it makes no such provision for secular Jewish male objectors. Ben-Artzi wants to do his service under civilian auspices, as Orthodox Jewish girls are allowed to do, but he wasn't allowed to. Refuseniks like him must go before a military panel that is bound by no legal standard and that almost never rules in their favor -- out of 53 requests between 1998 and 2000, only three were approved.

But as the military's overtures to Ben-Artzi suggest, it's gotten relatively easy for men to escape military service in indirect ways. According to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, 45 percent of the young people who are fit to serve in the army don't. That number includes Israeli Arabs and Orthodox Jews, but it also includes many mainstream Israelis who claim to have psychological problems. "The army encourages people who don't want to serve to get out the back door, to play crazy or fake mental problems," refusenik Haggai Matar told Salon last year before he was imprisoned. Those who refuse to lie about their politics go to jail.

Ben-Artzi's supporters say that's because their defiance threatens the established order in a way that the religious and the mentally unfit don't. "The military in Israel is a very prestigious club," says Sfard. "The club belongs to men of a certain sort. Now, here comes a group of men that are exactly of the sort the army wants -- members of the elite -- and they say, 'We do not want any part in this.' I guess that threatens this establishment."

Ben-Artzi was also an early signer to the so-called Seniors Letter, a declaration by 62 high school students of their refusal to join the military. Sent to Ariel Sharon in August 2001, it read, "We the undersigned, youths who grew up and were brought up in Israel, are about to be called to serve in the IDF. We protest before you against the aggressive and racist policy pursued by the Israeli government's [sic] and its army, and to inform you that we do not intend to take part in the execution of this policy."

The letter has since garnered more than 300 signatures. Matar, who helped write it, has been in jail for five months, and on Wednesday he, like Ben-Artzi before him, was court-martialed and ordered to stand trial.

Matania believes the army wants to strike a blow against the open dissent sparked by the Seniors Letter. "The army somehow identified Yoni as the leading figure in this movement," he says, adding wryly, "Israel's really integrating into the Middle East. There are now two main powers that control everything -- religion and the military."

Behind that transformation are people like Prime Minister Ariel Sharon (who Matania says leads a "junta") and Netanyahu, an ultra-nationalist who is a veteran of an elite anti-terrorist unit in the Israel Defense Forces. Unlike Sharon, Netanyahu openly opposes the creation of a Palestinian state -- which is why Sharon recently bumped him from his role as foreign minister and made him finance minister. Ben-Artzi's family says Netanyahu has never commented on his nephew's case except to say that he hopes Jonathan changes his mind.

There seems little chance of that. Recently, Ben-Artzi wrote a letter to his supporters saying, "With every day that passes, I gain new strength, which even those closest to me never thought I'd have ... Together with my fellow refuseniks, we will one day prevail in offering a truly peaceful alternative to Israeli militarism."

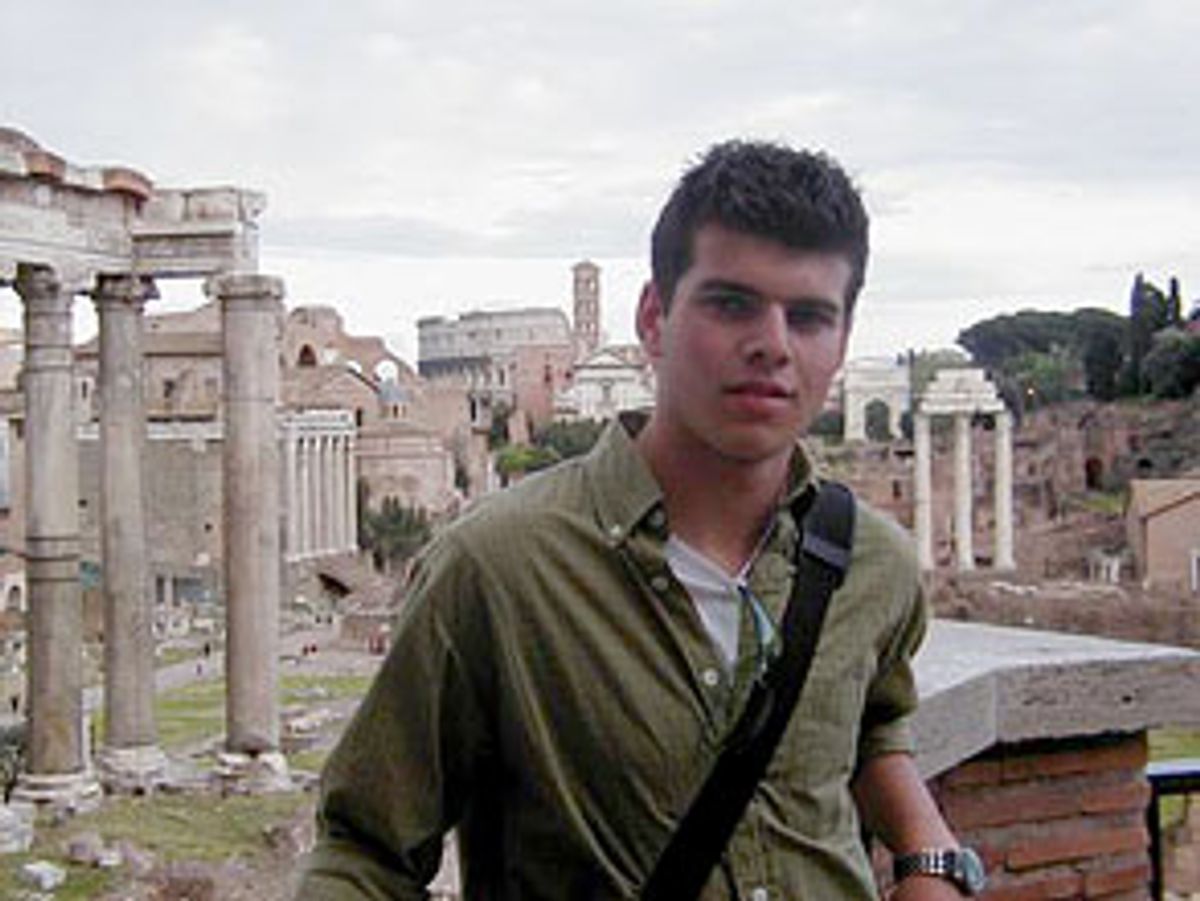

A math whiz who looks more like a "Dawson's Creek" star than a political prisoner, Ben-Artzi is one of 10 young men currently locked up for resisting the draft. So far, their jail terms have been handled as a matter of military discipline. Upon being called up and refusing induction, each was sentenced to about a month in prison. Each time their sentence is up, they are given another chance to join, and each time they refuse, they're sent back to captivity. Of the 10, Ben-Artzi has been in prison the longest -- longer than any other military refuser in Israeli history.

The upcoming military trials represent a new phase in the refuseniks' conflict with the army, one that will set a precedent for how the military deals with conscientious objection. Ben-Artzi's family hopes it will force the Israeli Knesset to formalize the status of conscientious objectors and institute a civil alternative to military service that would allow war resisters to serve their country without taking up arms. The IDF hopes to lock up the young man, who a prosecutor described as "no better than any deserter or drug addict," until he's 23, discouraging others from following in his footsteps.

While some of the refuseniks object to army service because of Israel's presence in the occupied territories, Ben-Artzi's family says that he's a committed pacifist who wouldn't serve in any army. It's a belief the precocious boy formed when he was 13 or 14, his father says, during a weekend trip to northern France. Matania is a mathematics professor who has taught at Berkeley and Princeton, and that year he was teaching in Paris. When Jonathan visited his father during the Passover vacation, they went to Verdun, the site of a major World War I battle in which 700,000 soldiers died.

"Verdun has sort of a mild New England landscape with rolling hills," Matania says. "It's the ultimate in serenity, and then you see stretching to the horizon tens of thousands of graves. There's a huge structure overlooking the valley that houses the unidentified remains of 150,000 soldiers. Yoni says this was an emotional shock for him, and it started him on a conscientious understanding of the evils of war."

He read deeply into the literature of pacifism and wrote about it every chance he had at school. In high school, he refused to participate in field trips to army bases or on outings that passed through the occupied territories. Yet according to Ben-Artzi's family, the military panel weighing his refusal to serve decided that his history "as a fighter" proved he wasn't a pacifist, even though his "fighting" involved passive resistance.

"It didn't matter that he's a fighter for principles," says Ruth.

Shares