I am well aware that my speech is the only thing that stands between you and your diploma. Thirty-five years ago, when I was a senior at Georgetown, we used to have commencements outside. Our commencement speaker was Washington, D.C., Mayor Walter Washington. Just as the mayor got up to speak, a huge storm cloud came over. The mayor looked up, and this was the speech he gave, verbatim: "Ladies and gentlemen, if we don't get out of here, we're all going to drown. I will send you a printed copy of my remarks. Congratulations and good luck." Our class loved Mayor Washington, and I will try to remember his example here today.

I've been touched in many ways by this city and this great university. I have been grilled extensively by Ted Koppel, Class of 1960. I have watched sports called by Bob Costas, Class of '74. I have danced to a lot of music played by the ageless Dick Clark, Class of '51. That's unbelievable. [Audience laughter.] Something in the water in Lake Onondaga. I love this city. I come to the state fair every year with Hillary. I've vacationed in Skaneateles. I have eaten more Dinosaur barbecue than any person who does not live in the city of Syracuse.

And as a longtime and utterly fanatic basketball fan, I watched with awe as Syracuse rolled through the NCAA tournament. I got to shake hands with Coach Boeheim today, and I was thinking how remarkable it is that he came here in 1962 as a freshman when President Kennedy was in office, then was co-captain of his college team with the great Dave Bing in 1966. He stuck with you for a very long time. Coach, congratulations on a job well done, and thanks to you and the team for the gifts of a lifetime for all of us basketball fans who will never forget what happened.

The world you enter today in 2003 may seem very different from the world you left when you embraced the confines of Syracuse in 1999. In 1999, the economy was strong; the world was making progress toward peace in Northern Ireland and the Middle East, Bosnia and Kosovo. Science and technology seemed to offer limitless possibilities for progress and prosperity. Since you came here in that year, you have seen a close presidential election resolved in the Supreme Court; a lethal attack on the United States in New York, Pennsylvania and Washington; conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq; the continuing war on terror; the failure of many high-tech companies; and the reversal of economic progress.

Here's what I want to say to you as you go out with your education. There's a big difference between the trend lines and the headlines, and one of the things that you need to be able to do as you leave here is to draw that distinction: to understand when you see a headline, if it's troubling or good, whether it's consistent with the trend line. And to know that it is your job as citizens, either of our country or of some 70 other nations from which you come, to try to build your trend lines. For the world of 1999 and the world of 2003 are actually not so very different. In 1999, we had the dangers of terror and weapons of mass destruction -- it's just that they weren't in the headlines because they hadn't happened here. But we were working hard to deal with them.

And in 2003, I think of all the things that have happened that are good in the four years you've been here. An international consortium of scientists sequenced the human genome, opening the prospects that those of you who are students here, when you bring your babies home from the hospital, they'll have little gene cards that will tell you what their strengths and weaknesses are, and how to raise them so their life expectancy soon will be about 90 years. Raising the prospect that, along with advances in nanotechnology, all cancers will someday be curable because you will identify tumors at submicroscopic level, before they can metastasize. Our great adversaries in the Cold War, China and Russia, have largely been reconciled to the West. And you don't worry about a nuclear explosion destroying all of humanity, as I did when I was your age. America is reaching out to Africa and the Caribbean in trade; the president is supposed to triple America's AIDS efforts to help people deal with HIV and AIDS. The rich countries of the world gave an unprecedented amount of debt relief to the poorest countries if they would agree to put their money into healthcare, education and economic development. That, too, happened while you were here.

So what I want to say is, whether in 1999 or 2003, you live in a world full of positive and negative developments, and they are related to each other. In 1988, when Pan Am 103 went down in Scotland, and those wonderful students from Syracuse perished, it marked the beginning of America's clear vulnerability to global terror, although we had lost people in the '70s and early '80s too. On September 11, 2001, we lost people from 70 nations in our country. But today, we will give diplomas to people from 70 nations.

So there are good headlines and bad headlines. The trend line is, we are growing more interdependent. We cannot escape each other. We reap enormous benefits and assume greater risks. Your job, as a citizen of this country or some other, as a citizen of the world, is to spread the benefits and reduce the risks, to move us from an age of interdependence to a global community where we share values and benefits and responsibilities. That is the trend line.

You can't stop the bad headlines, and even if you ignore them, there'll always be good headlines. But I want the trend lines to be right for you. Therefore, even though I disagree with the position France took in the recent conflict over Iraq, I think too much has been made of it. Because the trend line is toward cooperation. Did you know that there are only two groups of soldiers in Afghanistan today, where the people live who caused September 11, who are training the new Afghanistan army -- French soldiers and American soldiers, working side by side. That is the trend line. There are German and Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan. All the people who thought we were making a mistake on the timing and substance of Iraq supported us after we lost all those people on 9/11. That is the trend line, and that is what we should think about.

Let me give you another example. About a week before the NCAA tournament began, a little less than two months ago on March 15, the World Health Organization issued a global alert warning of a new virus in southern China. Scientists now believe the epidemic was spread by a single sneeze or cough at Hong Kong's Metropolitan Hotel on February 21. That's the disease we now call SARS. It came amazingly quickly, about the time the military conflict in Iraq started, but it is very different. First, no army can fight a microbe, even the best military in the world. Night-vision goggles don't protect you against a sneeze. And how can you seal off a border like America's border with Canada? The last invasion from the north came in the War of 1812. Syracuse students cross this border all the time. And that puts you on the front lines of the North American battle against SARS.

Now, how was SARS fought? Here's the trend line, not the headline -- although in this case, they're pretty similar. It was fought by international cooperation. In particular, by the World Health Organization, an arm of the now-reviled United Nations. The WHO alerted the world to the emerging danger of SARS. It pressured the Chinese government to be more open and give more information for the benefit of its own people and trading and travel partners. And it was a 46-year-old doctor from WHO, Dr. Carlo Urbani, who first identified SARS, first warned the world, and became one of SARS' first victims. That U.N. employee gave his life so that you could be more safe.

I say this because we have to remember the trend line. We have lots of problems with infectious diseases. Only about 435 people have died from SARS, although it is extremely virulent. During the same period, every single day, 8,000 kids have died from preventable childhood diseases. Every single day. One in four people [who will die] in the world this year will die from AIDS, TB, malaria and infections related to diarrhea. Last year, three million people died from tuberculosis, and over a million from malaria. Forty-two million people are infected with the HIV virus. That's one of the reasons that I spend as much time as I do in Africa and the Caribbean, trying to roll back the infection rate, because if we don't deal with infectious diseases, they will have not only bad human consequences, but also bad economic effects and bad political effects.

The same arguments apply to global warming and poverty. So here's my argument: We need a strong security policy. We should have a strong military. Sometimes we have to use it. But over the long run, the trend line will require us to make a safer world by cooperating with others. Therefore, I think America should be just as determined to lead the world against the threat of infectious diseases, the threat of poverty and ignorance, the threat of global warming, as we are about leading the world against the threat of terrorism.

I applaud President Bush for proposing to triple funding from America to combat HIV and AIDS, including providing greater treatment to those with the disease in 14 poor nations in Africa and the Caribbean. I hope this money will not come at the expense of other global assistance and that more of it will go through the Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria, so that we can help all the nations that need it. But make no mistake about it. This is a big first step. This amounts to a 20 percent increase in our overall commitment to foreign assistance.

However, as wonderful as it is, it's just a beginning. Because America gives a smaller percent of its budget to proven assistance programs than any other rich country in the world. We rank 22nd out of 22. We could double our foreign assistance for fighting infectious diseases, ignorance, poverty and global warming. If you believe America should have a strong defense against terror, then it has to have a defense against these other threats and has to build a world with more partners and fewer terrorists.

You have an education -- go out and tell people you know that we should continue to build on President Bush's AIDS initiative until we have doubled our foreign assistance and we are doing our fair share to build a world with more partners and fewer terrorists.

I want to close with a very specific request. First, I hope that more of you will personally serve in the Peace Corps, AmeriCorps or tutoring or, even on modest salaries when you leave here, contributing to other people who do that. Not all the work of the world can be done by governments. Second, I hope that all of you will vote and will get involved in politics. Your generation, to be fair, has gotten a bum rap. You do more community service than any previous generation of young Americans, and you should get credit for it. But whether it is because you're turned off by the press coverage or by the insurmountable nature of the problems, you are less likely to vote and participate in politics than previous generations of young Americans. And that's a big mistake, because it does make a difference.

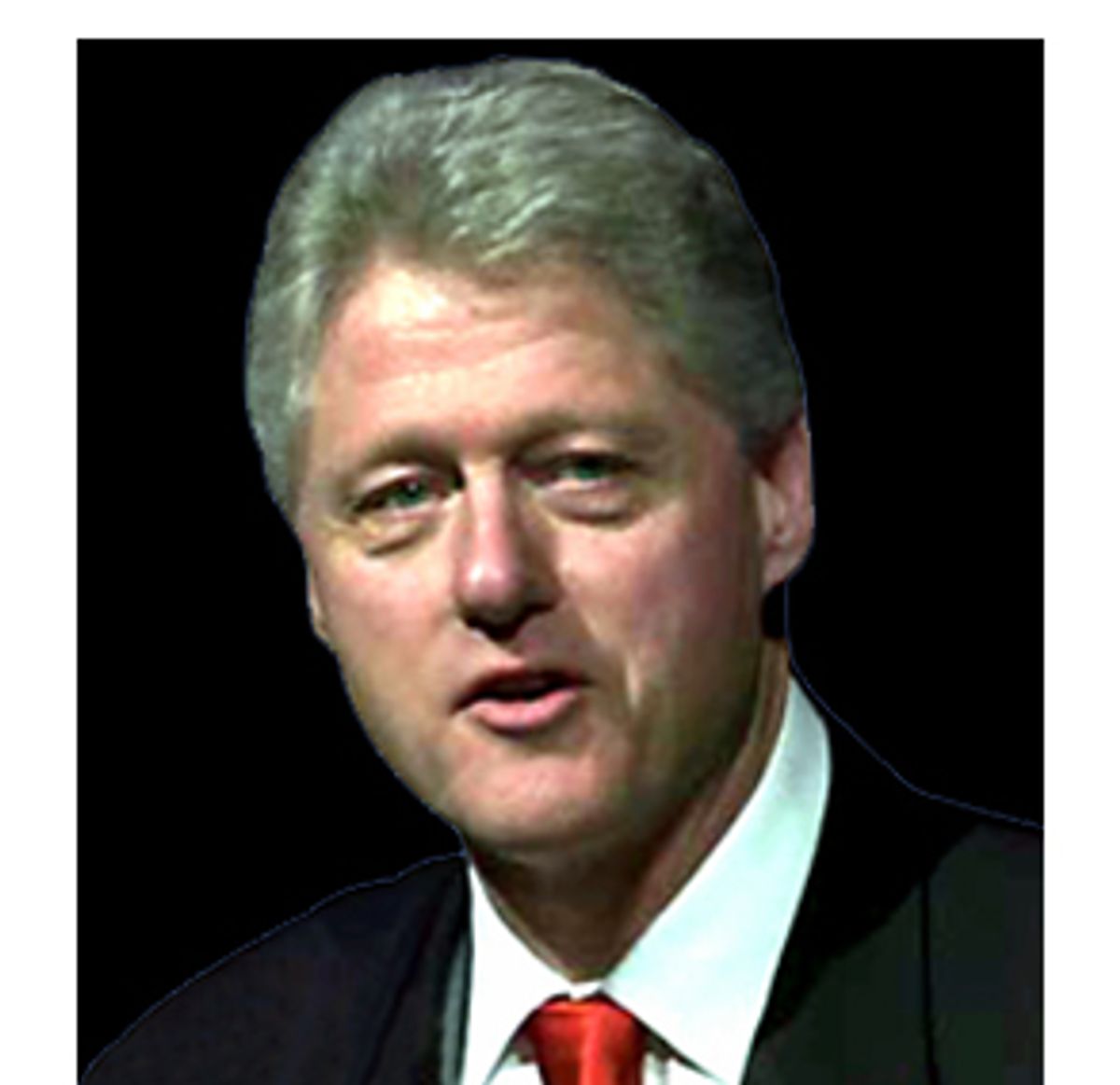

President Kennedy spoke here in 1957 and reminded the graduates, "The duty of the scholar, particularly in a republic such as ours, is to contribute objective views and a sense of liberty to the affairs of the state and nation." I can honestly say to you that after all the fights I've had, and I had some pretty good ones in the eight years I was president, on the day I walked out of the White House for the last time, I was more hopeful and more idealistic -- about the ability of free people to solve their problems and meet their challenges, and the ability of our system to change, survive, to improve, to form a more perfect union -- than I was on the day I walked in.

What I worry about is whether those of you who are willing to make those kind of sacrifices, who don't want power for power's sake, who aren't interested in defending some vested interest -- I wonder whether you are willing to make the sacrifice and undertake the burdens of public service and public participation. But I can tell you, don't you ever believe it doesn't make a difference. It does, and you must increase your involvement in American public affairs if you want the kind of world I have talked about today.

Now I want to make this one last point. I know you've got reasons to be scared -- people were scared after 9/11, so they quit flying around on airplanes for a while. People were scared about SARS and now, believe it or not, Hillary had to go down to Chinatown in lower Manhattan the other day to do an event at the restaurants because their economy has been devastated -- as if you're Chinese anywhere, you might be carrying SARS. There's a Japanese restaurant near my house where the business has fallen off just because people are generally afraid.

I want to say something about that. Fear is not a stupid emotion, and people who live without any fear are often stupid. But people who are paralyzed by fear are unfailingly miserable and unsuccessful.

The late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who taught here between '59 and '61 and came back here to the Maxwell School after he left office, wrote an amazing article in the Washington Post not long before he died, calling for "a return to the power of openness." By that he meant something very specific. Moynihan was upset that so many beautiful government buildings in Washington are closed to the general public because of fears about attacks. He said if the people who paid for them can't get in to see them, what good are they in the first place?

He also was making a larger point. If we're afraid to open our buildings or fly on airplanes or go to conventions or walk up the steps into meetings and speak our minds, then we have already given the terrorists and infectious diseases a victory. If we live in fear and reaction only, we have already consigned ourselves at least to a partial defeat. Moynihan was urging us not to respond to terror and fear in a way that compromises the character of our country or the future of our children.

So, of course, we have to stand against the bad things of the world, and, of course, we have to be afraid where it's appropriate. We only know how to deal with SARS, for example, through quarantining. But the genius of America, and a free and knowledgeable people of good will everywhere, is to work together to make a greater tomorrow -- not only to react in fear but to act in the hope and conviction and belief that for all the differences in this world we have, which make our lives much more interesting, our common humanity matters more.

All of human history can be seen in part as a race between the forces of the builders and the forces of the wreckers -- those who believe they have the total truth and they can only rise if someone else is falling. And every single time, since people first rose out of the African savannah a hundred thousand years ago, when it came down to it, the builders have prevailed. The people who believed in our interdependence have prevailed, the people who believed in our common humanity have prevailed. I want you to use your education to make sure that in the 21st century, we prevail.

Thank you, and God bless you.

Shares