It was in the air; in the minutes before I was arrested and taken to the Kufa mosque on Thursday afternoon, something was ready to go wrong. Muqtada's unbalanced soldiers, with scarves wrapped around their faces, stopped our car on the way to Najaf. As soon as it happened, a species of dread descended over the car; we knew the fighters were going to cause problems for us. One of them, a short, powerfully built man with a black scarf and wild eyes, told our driver to get out and open the trunk. I also got out and tried to talk to the men, but they wouldn't look at me, they would only speak to Abu Hussein, our driver.

Then the nasty-looking fighter with the black scarf, wired from his running battle with the Americans and furious with us for being Westerners, began to search the car. It was a haphazard but disturbing search because he was looking for incriminating documents, anything that would link us to the Americans. It seemed that Black Scarf wanted to show his comrades how seriously he could deal with foreigners trying to cross the checkpoint. Soon, other gunmen were attracted to the commotion and it became a kind of competition, an absurd closing and reopening of the trunk of our Chevy Caprice. We were nearly allowed to continue on our way, but then a new soldier arrived and found my video camera in the trunk. The sight of it riled him up, but also made him happy because it was proof of our guilt. This new soldier, not to be outdone by Black Scarf, pulled the camera out of its case, took my press credentials and safe passage letter and told me to come with him.

From the car, Minka Nijhuis and Abu Hussein watched the al-Mahdi Army take me off to the mosque. I walked with the fighters under a white sky scored with the black smoke of brick kilns.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

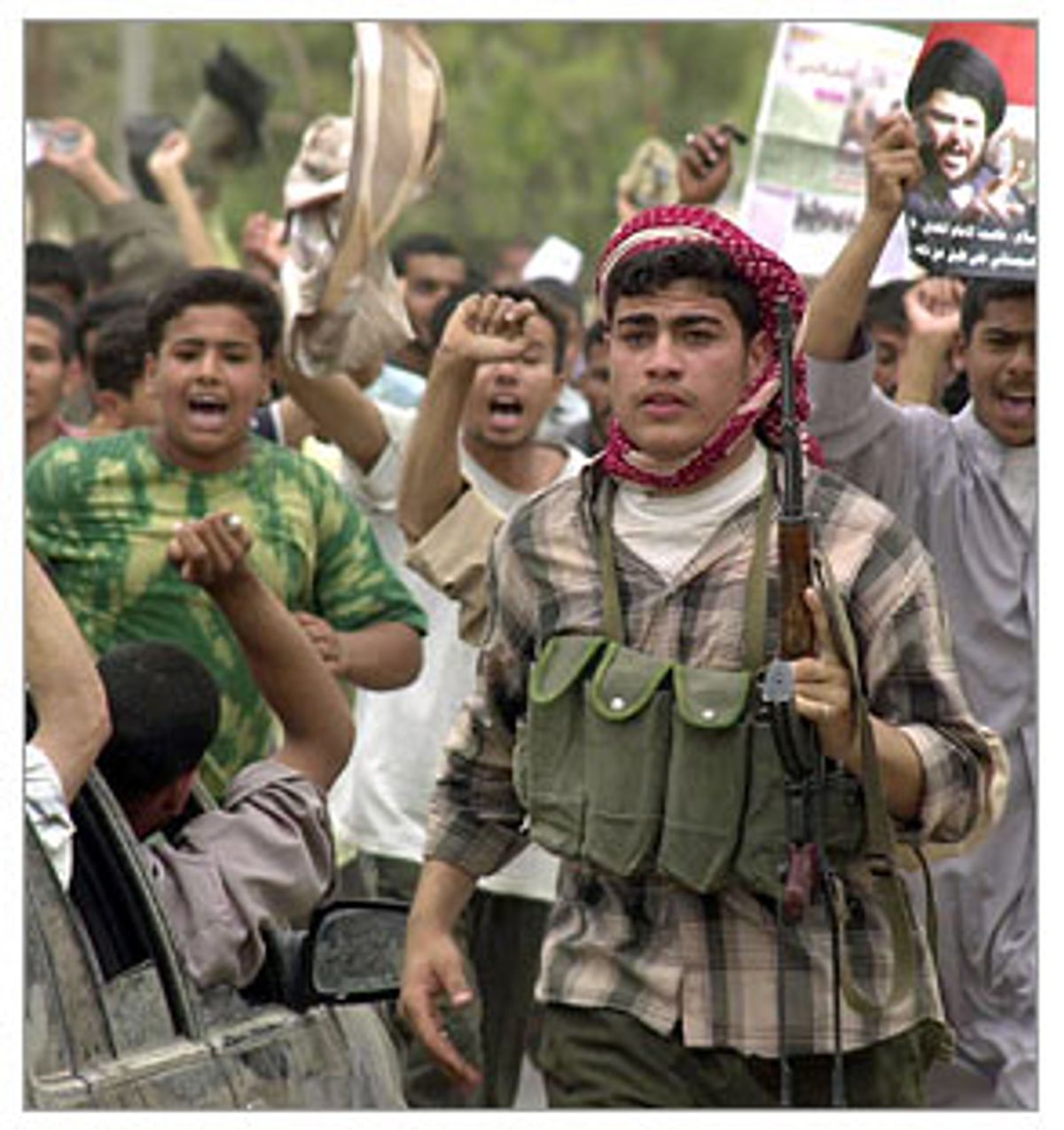

The day before, on Wednesday, Najaf and Kufa were going through strange convulsions. We had only been in Najaf for an hour when we saw how the arrival of the U.S. forces inside the city limits had enraged the al-Sadr militia. They had responded by repeatedly attacking the U.S. forces near Kufa and firing mortars at the base in Najaf. They were furious that the U.S. had taken a back route through the city when they showed up to relieve the Spanish forces. "Spies helped them find the way," a bearded captor would tell us the next day. When we interviewed the fighters in Kufa, they were in a state of near frenzy. They suspected all foreigners of collaborating with the coalition forces. They shouted their slogans at us, demanding we write them down. "You must write only the truth!" they said, gesturing wildly with visceral anger. "The Americans are liars!"

Abu Hussein, an agricultural engineer turned cabdriver, was the one who took us down through the long patchwork of desert and palm groves to Najaf. He didn't want to do it, but we talked him into it. We had to double his salary as soon as we got outside Baghdad. Minka Nijhuis, a writer from Holland, joined us. Sitting in the back seat, she looked like a scarecrow in her black abaya, which she was forced to wear because the religious authorities in Najaf wouldn't speak to her or let her near the mosque otherwise. Strands of hair kept leaping out from under the material, hindering her attempt at piety.

Just before crossing the Kufa bridge we saw that the U.S. had taken the main intersection where the road turned toward Najaf. The U.S. military now controlled the intersection that links Najaf to Baghdad and Diwaniya. There had been a fierce battle earlier in the week in which the U.S. claimed dozens of al-Mahdi Army had been killed; the al-Sadr militia had paraded their dead through the streets. The U.S. had moved in closer to Kufa, the two forces separated only by the bridge. And further down the road in Najaf, the U.S. had taken over the bases previously used by the Spanish. Kufa had become a sharply drawn front line.

On the opposite bank of the mud-colored river from the Americans sat al-Sadr's mosque and a host of barely controlled al-Mahdi fighters. It took Abu Hussein 30 seconds to drive the yellow cab from one zone to the next -- you could feel the shift immediately from U.S.-occupied Iraq to an isolated city controlled by Islamic militants.

When we drove through the last U.S.-controlled intersection and turned onto the bridge, everything was quiet. It was a bright cool morning, and the sky was full of sparrows. To the south, there was a palm grove and an open field. When we crossed over to the other side of the bridge, fighters were setting up mortars and machine guns in an attempt to stop an American advance on Kufa. Women were also out walking the streets with their children. Even with the feeling of a battle imminent, microbuses full of pilgrims deposited the faithful where they could worship at the site of Imam Ali's murder.

We drove on toward Najaf, passed the American tanks near the hospital and arrived at an al-Mahdi Army checkpoint where we were recognized. This particular checkpoint is the main gate to the city facing the Najaf sea, next to a rundown pilgrim hotel. An officer wearing a green T-shirt, a man named Ghazal, told me that he was a graduate of the local university and had studied economics before joining al-Sadr's army. He brought us into the shelter and gave us chairs. "I don't care about the tanks and the trucks and the bombs," he said. "I'll fight once, twice, three times, it doesn't matter. I want the Americans to get out. That's what is most important for me."

After talking to Ghazal at his post, we walked to the shrine of Ali, then turned into a narrow street where the Sharia court conducts its business. Without a permission letter from the court, we were not allowed to interview people in Najaf, nor were we permitted to travel to Kufa. Taking pictures was out of the question. So we waited around for an official to give us the magic letter, which also acts as a visa for foreigners in the al-Mahdi zone. A man came out and said that all the important al-Sadr sheiks were away at prayers. We milled around in the alley while more sheiks in their long black robes and immaculate turbans moved through the door without appearing to notice us. They moved with a practiced nobility; their court, set in the narrow alley, is the real center of government for the holy city.

Sitting on the ground outside the court was a man in a corduroy work shirt, not the black shirt of the al-Mahdi fighters. He was covered in dust and quite agitated -- he looked like he had been beaten. When he noticed that we were watching him, he rolled up his sleeves and showed us thickets of red welts covering both his arms. We asked him who did it. "Some men of the al-Mahdi Army," he said. One of the Sharia court guards was listening to the man tell his story and quickly jumped in. "This man takes drugs and he is a liar. He is a bad man."

Abu Hussein continued, unsure about the wisdom of acting as a translator for the man in the corduroy jacket. After the guards jumped in, the injured man changed his story. "All of the people who attacked me were saying they were from the al-Mahdi Army, but they were not from al-Mahdi Army. Maybe the men in the group were lying." He was trying to placate the guards, but we couldn't get his name before they brought him inside the court and shut the door. An official told us to go away and come back later for our permission letter. The walls had a few posters that begged for information about missing family members. One of them looked freshly posted.

In the square in front of the shrine of Ali, pickup trucks full of armed fighters rolled up and the men chanted the Muqtada chant. Najaf just a week before had seemed somewhat welcoming, but the mood was turning ominous as night came on. The fighters paraded with heavy machine guns and rocket launchers, declaring their allegiance to the cause. We were watching this spectacle when a reporter for al Jazeera gave us some startling news. An American peace delegation had just arrived to stop the U.S. invasion of Najaf. "They are staying in my hotel!" Ahmed Samarrai told us after he had predicted there would be a very great battle that night.

It turned out to be a small group of American peace activists, hoping at least to forestall a U.S. attack. "We don't have delusions of grandeur; part of our presence here is symbolic," Meg Lumsdaine told us, when we walked into their meeting in the Najaf Sea hotel. It could have been a Quaker meeting or a prayer circle -- five people sitting on plastic chairs near crates of soda pop. A bright blue banner on the floor said, "USA Don't Be the New Saddam. Come Home!" Lumsdaine is a Lutheran pastor; she and her husband Peter had come here to stop the U.S. invasion of Najaf. Three other Americans were with them: Mario Galvan, a public school teacher from Sacramento, Calif., Brian Buckley from Virginia, and Trish Schuh. This was the Najaf Emergency Peace Delegation, a few temporary human shields for the people of Najaf. "We wanted to stand in the way and say no," Peter Lumsdaine said.

The delegation had met with American soldiers that afternoon, not long before we spoke. Incredibly, Meg and Peter's group had marched with their banner toward a base of U.S. soldiers who were being fired on regularly by al-Sadr's militiamen. They walked down an empty, dusty track devoid of checkpoints or soldiers, and when they had gone a certain distance, a guard fired a warning shot in the air. The delegation did not turn around. Instead they waited until soldiers from the base came out to meet them. Meg was then allowed to speak to a representative from the Coalition Provisional Authority.

"They respected our willingness to come all this way. They were willing to talk, but I don't think they were willing to listen," Meg said. On Thursday morning we made a second try for the al-Mahdi Army permission letter. We lurked around the shrine of Ali for an hour but the sheikhs were tired of us and wouldn't write it. We begged the Sharia court receptionist, a giant of a man named Mr. Raad, to write the letters and have a sheik sign them. He promised he would do it. When the fighters stop foreigners and shout, "Wen kithab!" it is this letter that they want. If they do not get it, they become unreasonable. The small pile of letters and cards I had kept from the al-Sadr people from my last trip here were now worthless; only a new letter would be valid.

We drove back to Kufa and visited the local university without permission, a cluster of buildings that sits on the river in the line of fire. The gates were closed but not locked. We walked in calling out "Salaam Aleikum." Someone answered and four men appeared from the empty buildings, caretakers who were staying there at night to protect the facilities from looters. They were brave enough to speak their minds about the Mehdi Army.

"No one here likes the fighting, Mr. Riyal said. "Before the war, my salary was low, and now it is much higher. I don't want to lose this life now that I have it." In Arabic he told Abu Hussein, "I am now eating the bread," an expression that means he was able to provide for his family with his wages.

Shells had exploded on al Kufa University's roof, probably fired by a U.S. attack helicopter. One had smashed through some tin and sprayed a door with shrapnel. Another had landed close by. "These are new, " Mr. Riyal said. I wanted to know if there were any fighters using the university and its roof for a perch, but the men said no. There were no shell casings lying around, but it was impossible to tell for sure. We got ready to leave, and asked if we could come back to the university later for a visit. All said we would be welcome; they were not with al-Sadr and wanted nothing to do with him.

Later we drove back toward Najaf through Kufa's main traffic circle in the hope of one last interview with Ayatollah ali Sistani's representative. It was about a hundred meters farther down the road, when Abu Hussein drove us up to the checkpoint across from al-Sadr's mosque. All around Kufa men were getting ready to fight the Americans.

Indeed we had crossed the checkpoint at a bad time and they stopped us thinking that we were spies. Before we could get a plan together, two fighters were escorting me across the road to the mosque.

The fighters brought me into the courtyard and made me wait while one man went ahead with my confiscated credentials and camera. No one spoke to me or looked at my eyes. The commander with the gear disappeared into the buildings and then I was taken to an alcove near the door. It looked like a prison. I tried to refuse to go in, but they made me. For some reason, the fighters wanted me hidden, and forced me to sit down on a bucket behind a piece of corrugated tin. Two fighters came into the alcove to sit with me.

Back at the car, Minka, the writer from Holland, and Abu Hussein had their chance to leave and go work things out with the authorities in Najaf; they weren't under arrest and the fighters didn't know what to do with them. But after a few minutes, they appeared at the gate of the mosque to try to get me out. Then the al-Mahdi fighters arrested them. Minka was briefly stuck in the alcove with me, but the fighters apparently decided it wasn't proper to mix a woman in with the men, so she was taken out and moved to the ladies section of the mosque. While I was being interrogated by a gangly former chemistry student, Minka was being searched, very roughly, by the secret female police of the al-Sadr militia. Some of them wore black flak jackets under their abayas. They opened Minka's toothpaste and tasted it, tried on her sunglasses, puzzled over her contact lens cases. Her satellite phone was taken away. But before long, the ladies offered her sweets. "They have been totally brainwashed," Minka said about them later. "They don't know anything."

The chemistry student had some basic political questions for me. He was very curious about my nationality, which I repeatedly lied about -- he asked several times. We moved on to other topics. He allowed me to smoke with him as we talked. They gave me water, which is routine courtesy, and then they asked if I wanted to join the al-Mahdi Army. I declined, saying my eyesight was terrible.

One poor young man asked about my religion, and when I explained that I am not religious, he was appalled. "You know the Imam Mahdi is coming back from the dead," he declared. He did seem like a person who was ready to die for his beliefs.

I realized that what I was seeing was the real al-Mahdi Army, without the fanfare and flaunting typically put on display for the press. Some of them were barely more than wild-eyed children, led by half-educated young men full of revolutionary fervor.

Before long Abu Hussein reappeared with two guards and, looking very depressed, said that he was under arrest as well. To show this he crossed his wrists like they were bound. He had been threatened by them and treated far worse than we had been. They took him to an office deep in the mosque and charged him with a crime. A sheet of paper with the charge was prepared for the sharia court in Najaf.

After some time, the female fighters reappeared with Minka and we were walked across the street toward the car. For a moment it seemed as if they were going to let us go. I asked Abu Hussein if we could head out of town. "No, we can't." I asked if Minka could leave. "No, she can't leave either." Surely they told Abu Hussein what they were going to do with us. But he didn't know what was going to happen any more than we did and he stopped talking to me, angry to be in this mess.

Minka was calm if not cheerful. From time to time, one of the bad fighters would shriek at her to push her hair back under her abaya. Across the street was another base full of Muqtada people. Older men asked us the questions. "Are you from Reuters?" one commander said. "Just answer yes, or no." I said that I was not from Reuters, suddenly wishing intensely that I was. The fighters liked Reuters people, we learned. While we waited Abu Hussein talked and joked faster and better than any translator I have worked with; he slapped our captors legs, and made friends, and he helped get us moved out of Kufa.

While we were being questioned, three rocket-propelled grenades detonated nearby; the fighters were launching their attack. A U.S. military flak jacket was perched on a chair in the garden, which I remember very clearly. The fighters no longer had time for us. We were led out to the car, where a new man showed up carrying all our gear. He would take us to Najaf. Another man took our driver's car keys and got in the front seat. An ambulance turned the corner, and the men suspected it of carrying Americans so they fired at it to stop it.

With Abu Hussein crammed in the back seat, we pulled out into traffic and headed out of Kufa into the countryside. It bothered me that we were headed out of town going north, the wrong direction. Our new jailer was taking back roads that were free of U.S. tanks. We were driven through Iraqi police checkpoints out into the country before finally veering west and then south toward Najaf.

As we came up on Najaf from the north, we entered a vast necropolis. Hundreds of thousands of sleeping dead covered a rolling plain with 1,400 years of crypts in the sacred soil. "It is a gift for them in the afterlife," the captor said. We drove past the dark holes where families could commune with the dead in the cool shade. The Najaf necropolis is the secret route for al-Mahdi fighters to move in and out of the city; it is traversed by a network of thin roads that they know very well. A friend once showed me snapshots of arms caches and firebases within the graveyard.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Later, as we enter Najaf, Ghazal, our friend at the Najaf Sea checkpoint, instantly sees that we are under arrest, and comes over to explain the situation to our captors from Kufa. He tells the older official in the front seat that we are OK, not spies at all. When we arrive at the sharia court, the giant Mr. Raad waves two sheets of paper in our direction, the letters we'd requested but had not received in time. Once the letters were inspected and found to be accurate by an Islamic judge, we were freed on the spot. The al-Sadr people apologized, but it was too late. We had seen what we needed to see. Back inside the mosque, the boys -- my captors -- taught me the chant. It goes like this.

Allah humma

Sallee Allah Mohammed

Wa'ali Mohammed

Wa'adjil farajahom

Wala'an aduahom

Wansur waled'ahom

Muqtada, Muqtada, Mouqtada

Ya'allah, Ya Mohammed, Ya Ali, Ya Mehdi!

Unsurnah!

Dear God

Greet Mohammed

The Twelve Imams

People cry out to God to send the Mahdi

Send the enemies to hell

Give victory to him

Muqtada, Muqtada, Muqtada!

Hail Allah, Hail Mohammed, Hail Ali, Hail Mahdi!

Give us victory!

Shares