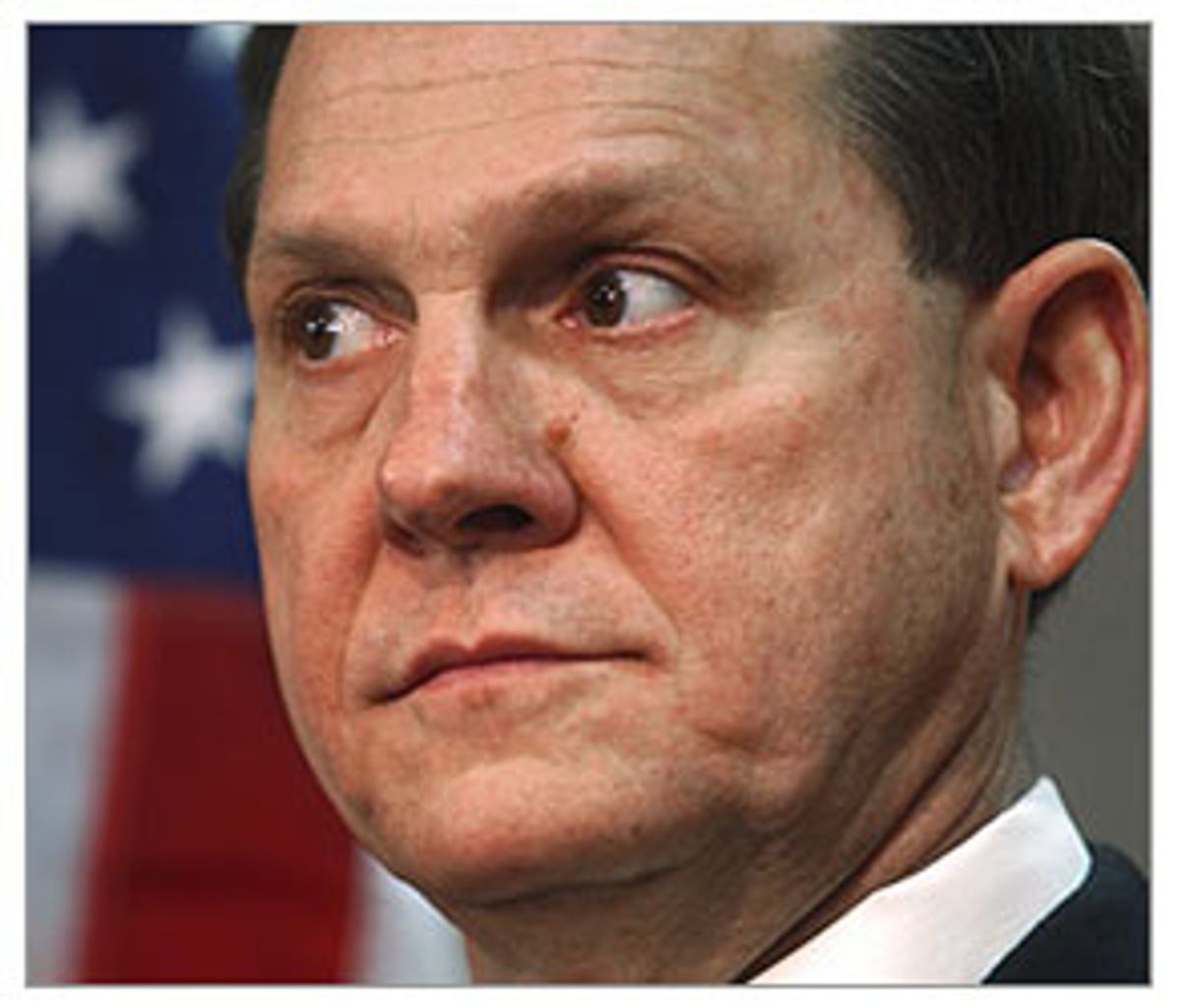

Alabama's renegade Chief Justice Roy Moore was already the darling of the far right when he rallied cheering supporters on the steps of the state courthouse last August. Nationally known as the "Ten Commandments Judge," Moore had installed a 5,280-pound granite sculpture of an open book inscribed with the commandments shortly after he was elected in 2001, and then defied a federal court order to remove it. Observers couldn't help being reminded of Gov. George Wallace's infamous stand in the schoolhouse door, rallying Alabama segregationists in defiance of a federal court order to integrate the University of Alabama.

Now, almost everywhere Moore goes, people ask him to do something else Wallace did: run for president.

The possibility that Roy Moore could challenge President Bush in November may not be costing Karl Rove any sleep -- yet. But the chance that the popular conservative judge could do to Bush what Ralph Nader did to Al Gore in 2000 -- split his ideological base, and cost him the presidency -- has analysts crunching numbers and weighing Moore's chances. Moore and his spokeswoman did not return telephone and e-mail messages from Salon, but Moore's public statements have been consistent in recent months. He is keeping his options open, he says, and he will decide if he will run when he has exhausted his court appeals in the Ten Commandments case.

Meanwhile, the 57-year-old Moore is acting more and more like a candidate as he crisscrosses the country, speaking at gatherings of Christian rightists, home-schoolers and state conventions of the far-right Constitution Party, which was on 41 state ballots in the 2000 election, and is courting Moore to head its ticket. If he ran on the Constitution Party ticket, he would probably be on more state ballots than Nader this year. With 320,000 members it is the third-largest party in the U.S, in terms of registered voters.

Will the dynamics of the race change if Moore throws his hat in the ring? Hastings Wyman, a former aide to the late Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., and editor of the Southern Political Report, thinks so. Wyman told Salon that he thinks Moore has the potential to "do to Bush what Nader did to Gore." Other Republican and Democratic strategists aren't so sure, but no one thinks Bush can stand much erosion in his base. Certainly some Republican leaders take Moore seriously enough to quietly court him, hoping to keep him in the party and preserve the president's Christian far-right constituency.

The deadline for Moore to declare himself is the June 22-26 Constitution Party national convention, in Valley Forge, Pa. Even a few months can be an eternity in politics. But in recent weeks, Moore has spoken to Constitution Party state conventions in Oregon, Montana, Pennsylvania, Nevada and Ohio. And a Moore for President Web site has popped up. Meanwhile, Moore, like many a pol before him, is keeping his finger to the wind and everyone at the edge of their seats.

And the judge doesn't discourage comparisons with Alabama hero George Wallace, by the way. When a reporter for the Seattle Times observed that the judge's analysis of the two major parties sounded like Ralph Nader's, Moore agreed, and added, "As somebody from our state, George Wallace, once said, 'There's not a dime's worth of difference between them.' It's all about power. I think the people need a choice."

Moore's rise to national prominence began in 1995. The ACLU sued Moore, then a state Circuit Court judge, because he posted a hand-carved plaque of the Ten Commandments in his courtroom and opened court sessions with Christian prayers. His stand became a statewide sensation. "God has chosen, through his son Jesus Christ, this time, this place for all Christians -- Protestants, Catholics and Orthodox," declared state Attorney General William Pryor at a pro-Moore rally at the time, "to save our country and save our courts." Then-Gov. Fob James threatened to call up the National Guard to defend Moore and the Ten Commandments against the feds, if necessary. A federal judge eventually ruled that the ACLU'S clients lacked standing in the case -- and Moore rode a wave of popularity to the national lecture circuit and election as chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court.

Moore says he won't decide about a presidential run until he exhausts all appeals in his Ten Commandments case. He fought repeated orders to remove the rock, even after federal court appeals failed. Last November, his fellow justices of the Alabama Supreme Court (seven of whom are Republicans) decided they'd had enough, suspending Moore from office, and removing the monument. "People who govern in the name of God," said Justice Douglas Johnstone at the time, "attribute their own personal preferences to God, and therefore recognize no limit in imposing those preferences on other people." The state Court of the Judiciary then made the ouster permanent. Moore's appeal to a special court of retired judges, sitting in the place of the Alabama Supreme Court, was unanimously denied on April 30. Moore may appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Montgomery Advertiser, the major newspaper in the Alabama state capital, thinks Moore is just "teasing the Constitution Party" and that he would rather not risk playing the spoiler and help elect John Kerry. "But," the paper averred in an editorial, "if Alabamians have learned anything from Moore's past, it's that logic doesn't play much of a role in the decision-making of the Ten Commandments judge." And former Montgomery Advertiser political reporter Todd Kleffman, who covered Moore during the Ten Commandments fracas, predicts Moore will run. "Though he hasn't said it yet," Kleffman wrote recently in the Danville, Ky., Advocate-Messenger, "my hunch is that Moore will soon announce that he is running for president on the Constitution Party ticket."

Whatever his final decision, clearly Moore's crusade has made him a national figure who is wildly popular on the Christian right. He has become a fixture of both mainstream and conservative Christian media from CNN to Pat Robertson's 700 Club. Charismatic and a proven vote getter, Moore won his race for an open seat as chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court 878,480 to 726,348 in 2000. Now, as he barnstorms the country, he's galvanizing conservative Christians in a manner not seen since Oliver North was fired from his White House job in the wake of the Iran-Contra scandal. Wall Street Journal columnist John Fund wrote in February that he has seen Moore rouse the crowds at major Christian right conventions from Phyllis Schlafly's Eagle Forum to Pat Robertson's Christian Coalition. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Moore was "treated like a rock star" by the Christian Coalition, "signing autographs and getting thunderous standing ovations." Last month Moore addressed a crowd of about 1,000 Great Falls, Mont. "The crowd was very enthusiastic," says Travis McAdam, a researcher with the Montana Human Rights Network. "People were definitely there to see him [Moore]. And really liked what they heard."

It should come as no surprise that Moore has emerged as the dream presidential candidate for leaders of the Constitution Party, which generally views the federal judiciary as unelected tyrants. But the Constitution Party is also an improbable vehicle for any kind of national campaign. It is not only small, but its far-right platform and cast of controversial characters are arguably not ready for mainstream America and the glare of the international press.

Still, the party could give Moore a vehicle for doing some damage to Bush, if that were his goal, in at least a handful of key states, most notably Florida, where after ostensibly winning by 537 votes in the bitterly contested 2000 race Bush is currently running behind John Kerry in most polls. Ironically, Florida is the place where even those analysts skeptical about the impact of a Moore run say he could make a difference.

Last November, Moore appeared at the Crossroads Baptist Church in Pensacola, Fla., and packed the house with more than 1,000 cheering people. "The country has not seen the likes of Moore in many, many years," senior pastor Chuck Baldwin told the crowd, according to the Pensacola News-Journal. "He is a modern-day Patrick Henry and Daniel from the Old Testament." Baldwin is the choice for vice president of the only announced candidate for president, Michael Peroutka, party chairman in Maryland. But Baldwin, who is also a columnist and radio talk show host, has recently told a reporter that he would support Moore if he runs.

"After you have divided up the secure Bush states and identified places where 1 or 2 percent of the vote might make a difference," says Tanya Melich, a former Republican activist, and now an independent political consultant, "as I look at the map of states in play, there is really only one -- and that's Florida."

She doesn't think Moore would be much of a factor in his home state. "Alabama is such a solid Bush state," she told Salon. "I just don't see how it would go to Kerry." She sees a potential Moore factor in Louisiana, which went for Bush last time, but is "in play," since Democratic Sen. Mary Landrieu's reelection victory last year. Melich sees Minnesota (Gore) and Michigan (Gore) as possibilities as well, noting that George Wallace enjoyed substantial support in Michigan.

Micah Sifry, author of "Spoiling for a Fight," a recent book on third parties, thinks that Moore could potentially siphon off enough Christian right votes in Colorado (a Bush state last time) and Oregon (a Gore state) to put both states in play, to Kerry's advantage. But Sifry cautions that some who vote for third-party candidates are people who would not otherwise vote. So in a Moore campaign, Sifry concludes, "Some votes you take from Bush; some you take from nowhere."

Hastings Wyman cautions, however, that among conservative evangelicals "Bush is generally well liked, and there is not a lot of dissatisfaction with him."

Christian Coalition president Roberta Coombs agrees. She says Bush has "huge support" among conservative Christians, and that Moore would be unlikely to peel away much of that. But still, she worries. "I personally like Judge Roy Moore," she told Salon. "I admire the stand he took for the Ten Commandments. But I definitely don't think he should run. I think he could hurt the president."

The Constitution Party, founded by Howard Phillips in 1992, overtly advocates "biblical law" as the basis of government. Leaders of the Christian Reconstructionism movement, which advocates theocratic government under "biblical law," have also been party leaders from its genesis. These include the founder and seminal thinker of Reconstructionism, the late R.J. Rushdoony, whom Howard Phillips once called "my wise counselor."

The party is also home to many conservative Catholics and religiously motivated home-schoolers. The explicitly religious dimension is the tie that binds what, like any party, is a fractious bunch. But the party platform also takes stands on issues on which the far-right disagrees with Bush, opposing his immigration policies as well as NAFTA, the Iraq war, and the USA PATRIOT Act. Like Moore, the party believes that the role of the federal courts should be severely limited. In 1996, Phillips and his running mate, Herb Titus, urged state and local officials to shut down abortion clinics and call up the militia in case of federal intervention. Not surprisingly, the party is the political home for members of militia groups and militant anti-abortionists. For example, the vice chair in Ohio is J. Patrick Johnston, whose essay "Why Christians Should not Vote fore George Bush," is arguably the party's anthem this year. Johnston has also argued that the murder of abortion providers is "justifiable homicide."

Unlike the Green Party, which was able to attract Ralph Nader, a respected national figure, the Constitution Party never managed to lure a "name" candidate to head its presidential ticket over the last three presidential contests. Over the years it has courted Pat Buchanan, Alan Keyes, and former U.S. Sen. Bob Smith, R-N.H. -- who briefly bolted the GOP in 2000 and flirted with both the Constitution and Reform parties before returning to the fold. Each time out, party founder Phillips gamely carried the banner. Last time, the presidential ticket drew .02 percent of the vote -- reaching 1 percent in Connecticut, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Party leaders insist this year is different. Pat Buchanan will not be rallying his nativist "pitchfork brigades" to the largely defunct Reform Party, and Buchanan's running mate, Ezola Foster, is now a member of the Constitution Party's national committee. The party is already on the ballot in Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi. Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont and Wisconsin, according to the authoritative newsletter, Ballot Access News, and more states are planned soon.

Certainly Moore has a lot in common with the party. The former judge personifies a kind of theocratic right-wing populism that sees the federal government as its major opponent. For instance, he opposes the marriage amendment to the U.S. Constitution that President Bush recently endorsed. Though it's supposed to ban gay marriage, a goal he supports, Moore insists that meddling with the Constitution would give renegade federal judges the opportunity to twist it for their purposes. "Some judge," Moore speculated, "would probably let a man marry his sister or daughter."

Instead Moore thinks Congress should pass the Constitution Restoration Act, written by Moore and his attorney Herb Titus, which would prevent the federal courts from banning acknowledgment of God as the basis of law. "Marriage is the union of a man and a woman; it's a God-ordained institution," Moore told the New York Times. But if that is not the standard, Moore thinks "there's nothing to keep three men and a horse from getting married, or an entire city."

Some Republicans are trying to keep Moore in the party, and they're using his Constitution Restoration Act to do it. Last month Alabama Republicans Rep. Robert B. Aderholt and Sen. Richard Shelby introduced the act, which would also serve the purpose of retroactively removing the matter of Moore's monument from the jurisdiction of the federal courts -- along with "any matter" in which the "acknowledgement of God as the sovereign, source of law, liberty, or government" might be an issue. Last week, Moore secured a commitment from congressional leaders to hold a hearing. The bill, loudly cheered by the Constitution Party, is a good example of the way Moore is navigating the two parties as he surfs the rising wave of right-wing populist resentment. Even if Moore ultimately decides not to run, he has certainly used his celebrity to build the Constitution Party around the country, and leveraged his Naderesque political clout to advance his agenda.

Rev. Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, told Salon that he sees Moore using the legislation as a rallying point as he takes "his fundamentalist theocratic crusade nationwide." And yet Moore remains angry that he's gotten insufficient backing from fellow Republicans for his crusade to keep the Commandments in his courthouse, and to keep his job as chief justice. During his speaking gigs, he often shows a video in which Attorney General William Pryor makes the case against him before the Alabama Court of Judiciary. The implicit message is that Pryor personifies the GOP establishment's betrayal of Moore's vision of Christian constitutionalism. The betrayer in chief is, of course, President Bush, whose recess appointment of Pryor to the federal bench was supposed to please Christian conservatives.

"Bill Pryor was a professed Christian who had to choose between his Lord and his political career," said Jim Clymer, national chairman of the Constitution Party. "He chose his political career."

For his part, Moore told the Wall Street Journal's John Fund, "Bill Pryor made a decision on who he would side with, and I'm disappointed it's not with the people."

But the Montgomery-based Southern Poverty Law Center's Mark Potok, who has had a ringside seat on Moore's entire career, told Salon: "I think it was pretty clear that Pryor was genuinely angry at Moore and found his conduct outrageous and that it was not merely political calculus. There is a lot less sympathy for Roy Moore in Alabama than a lot of people might think."

Now, with Moore's appeals nearly exhausted, the day of decision draws nearer. Moore has used the court system to his advantage, as each new loss provides opportunities to further his case in the court of ultra-right public opinion. If Moore does appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, Danielle Lipow, an attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center, thinks the idea that he would have a constitutional claim is preposterous. "For him to claim that the state's ability to hold judges to their ethical standards somehow violates his rights is to turn the entire system of judicial ethics on its head."

"Could he file a federal claim?" she asks. "Certainly. It costs $150 to file." Would the claim have a chance of success? She doesn't think so, but adds: "If there were a book that included a definition of the phrase 'There is no such thing as bad publicity,' you'd find a picture of Roy Moore."

Indeed, it could be argued that Moore's showdown with the federal courts has been political theater from the beginning. Moore had the monument installed in the courthouse in the dead of night. He had not consulted his fellow justices, but he had a camera crew from televangelist D. James Kennedy's Coral Ridge Ministries on hand to film the occasion. Coral Ridge sells the video, and has raised money for Moore's legal defense.

Moore evidently set out to provoke a confrontation with the federal courts -- one he was destined to lose, much as Gov. Wallace had 40 years before. Wallace's provocative, mediagenic stands paved the way for his independent run for president in 1968. And though there are vast differences in time and the pressing issues of the moment, there are striking political parallels and one historic matter of constitutional substance: the jurisdiction of the federal courts vs. states rights.

But where Wallace hurt the Democrats, Moore's run would hurt Republicans. "This guy [Moore] is going to cut into a constituency that the Democrats lost a long time ago," says political organizer and Harvard lecturer Marshall Ganz. "To the extent that it became a threat, Bush will have to tack to the right, which would be very good for the Democrats."

Shares