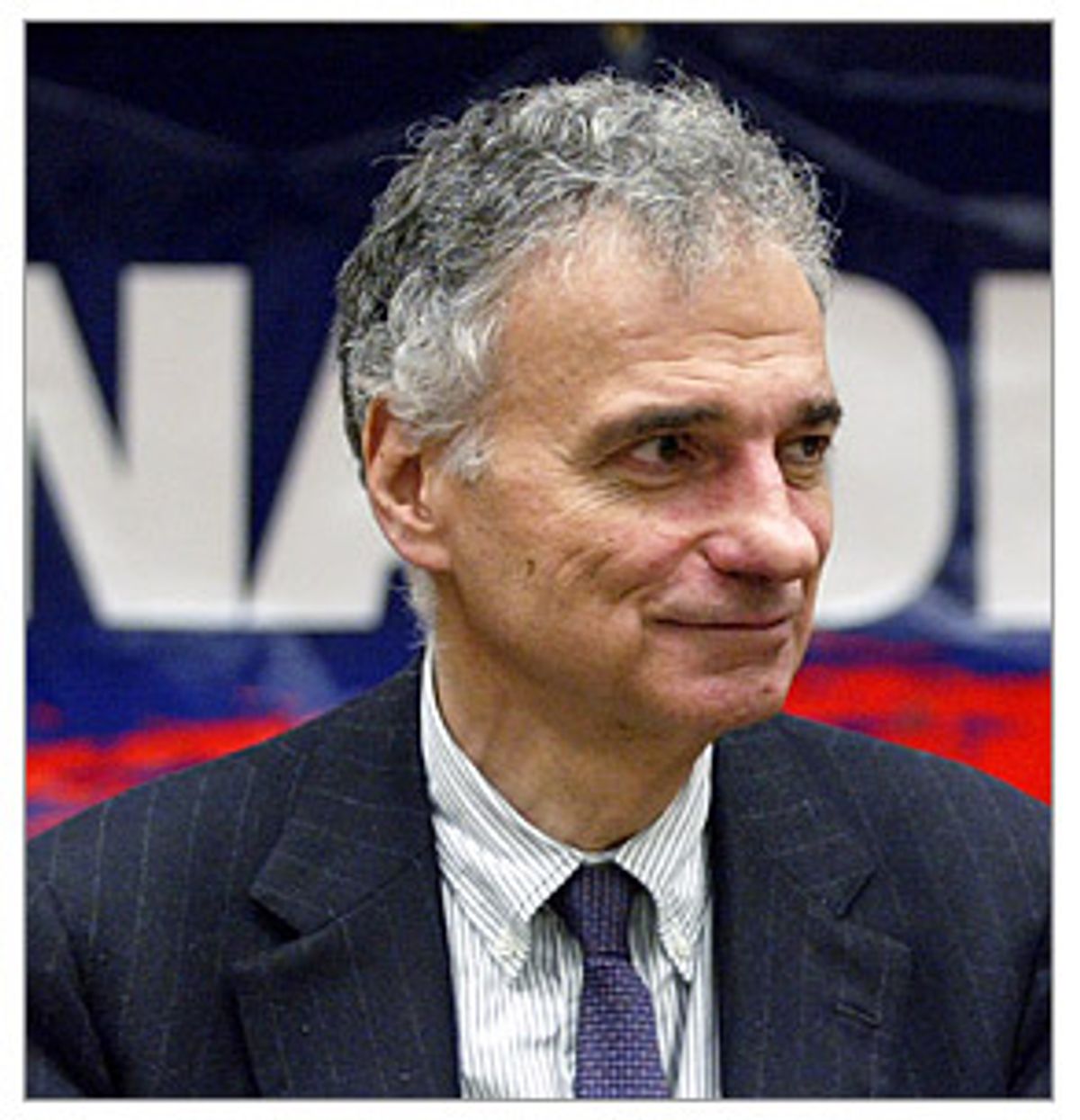

Ralph Nader spent his 70th birthday with Bill Maher on his HBO show "Real Time," where Maher pressed him on exactly what his controversial fourth presidential campaign will contribute to the national debate. Nader repeated once again that he's the only candidate not beholden to "corporate America."

While Nader's legacy as a consumer advocate is unparalleled, it is worth noting that the onetime national hero wasn't celebrating his landmark birthday surrounded by the hundreds of people he has worked with and influenced over four decades. Indeed, virtually no one who worked with him since the heady days of Nader's Raiders is supporting him politically or personally today. He has inspired almost no loyalty and instead has alienated many of his closest associates. The estrangement between Nader and many of his former intimates is not a new phenomenon; it's not the result of his ruinous campaign for president in 2000; it dates back to his earliest days as a public figure.

Dozens of people who have worked with or for Nader over the decades have had bitter ruptures with the man they once respected and admired. The level of acrimony is so widespread and acute that it's impossible to dismiss those involved as disgruntled former employees, disillusioned leftists or self-seeking turncoats. Usually it was Nader himself who ratcheted up what was often just a parting of ways into professional warfare and vitriolic personal attacks.

While Nader continues to campaign against corporate abuse, his own record, according to many of those who have worked closely with him, is characterized by arrogance, underhanded attacks on friends and associates, secrecy, paranoia and mean-spiritedness -- even at the expense of his own causes. If he were a corporate CEO, subject to the laws governing publicly held and federally regulated firms, there can be little doubt he would have been removed long ago by his company's board of directors.

Nick Jacobs' blood boils every time he sees another poll showing Nader within striking distance of costing John Kerry the election. For him, it isn't just that Nader was indispensable in President Bush's 2000 victory over Al Gore. Nader's latest run for president is infuriating for personal reasons as well.

"He puts himself out there as pure as the driven snow, and he's not," says Jacobs. "He's paranoid, secretive and manipulative, at best. It galls me that he talks about how corrupt the two-party system is when he trashed someone to the FBI who was his best friend."

That someone was Jacobs' father, Theodore Jacobs. Ted Jacobs met Nader when they were both freshmen at Princeton and then attended Harvard Law School together. Later, as an attorney in private practice, Ted provided personal and professional legal assistance to his old college friend after he was catapulted to national prominence over the issue of automobile safety with the publication of "Unsafe at Any Speed." Ted became, in effect, Nader's chief of staff. And from 1970 to 1975, Ted was executive director of the Center for Study of Responsive Law, the first organization Nader founded.

The two men's ugly and painful falling out -- in which Nader trashed Jacobs to the FBI when Jacobs was up for a federal job and Jacobs retaliated with an explosive affidavit alleging financial and legal improprieties by Nader -- was the first of many destructive breaches between Nader and onetime allies. The story hasn't been told before, but the Jacobs family recently made private papers available to Salon that document the sad split.

"My dad kept everything," said Jacobs. "He had boxes of papers in our basement. They pretty much sat there until Nader announced that he was going to run again, and I decided to go through them." Nick was shocked by his discovery of this dark chapter in his father's otherwise enemy-free life.

In various articles from the early 1970s, Ted Jacobs was described as "Nader's closest friend and advisor" and the person who stood "between Nader and the world, absorbing the fury of the attacked, offering solace to the ignored, always speaking the absolute truth within the limits of what he believes Nader would wish him to reveal." But, according to the private papers shared with Salon, he informed Nader sometime in 1974 that he planned to leave the Center for the Study of Responsive Law but would first finish several projects.

On March 8, 1975, Jacobs arrived at the office to find the contents of two large file cabinets missing (including his personal diaries and documents relating to "financial matters") and his desk drawers ransacked. Nader arrived at the office a short while later to tell him he had ordered the files removed. In a state of near shock, Jacobs tendered his resignation and demanded to know what was going on. According to contemporaneous notes written by Jacobs, Nader said he had confiscated the files because a year earlier, Jacobs had signed checks for magazine subscriptions without Nader's permission. Nader also accused Jacobs of writing a check to himself for about $75 for expenses. Dismayed and shaken, Jacobs searched for a new job.

He was being seriously considered for a position as a staff member on the Senate Select Intelligence Committee, which required a routine background check conducted by the FBI (which collects raw data on individuals but does not seek to confirm it). While waiting to hear about the job, Jacobs was told that questions had been raised about his character, honesty and trustworthiness. He subsequently learned that the source of the innuendoes was Nader. According to Jacobs' son Nick, to find out why he was denied a security clearance, Jacobs asked for and received a list of the people the FBI had interviewed and what they had said. He told the agency the accusations were untrue.

Nick says he has repeatedly asked the FBI for access to his father's FBI file, but although the agency has said the file is OK to release, he has so far not received it.

On Aug. 7, 1975, Jacobs wrote his former friend a letter expressing his distress: "I thought that we had settled after our long talk in April ... If I misunderstood you that day, it was surely the most costly misunderstanding in the 24 years I've known you. I was prepared to let you go your way in the hope that you would let me go mine and I was feeling very kindly disposed to you. That was until I learned of your statement to the FBI. The impact of that statement was as if I had been kicked in the stomach ... We must have some sort of resolution to undo the damage done by your statements. As the record now stands, it will be an impediment for the rest of my life."

It may be hard now to fathom just how credible and influential Nader was at the time. He had taken on General Motors and won, launched a new movement on behalf of consumers and recruited earnest young Raiders to work for organizations founded solely on his credibility. By 1975, Nader was regarded as an exemplar of righteousness, the ultimate advocate of the ordinary citizen. For someone of his stature to impugn the reputation of a former employee to the FBI was devastating.

According to a statement Jacobs wrote after he was dismissed, Nader told the FBI that Jacobs was fired for skimming money from the Center for the Study of Responsive Law and other irregularities. In the affidavit that Jacobs drafted in the hope of clearing his name with the FBI, he wrote: "I was the only person Mr. Nader trusted with his extensive and complicated financial dealings ... I regularly signed his name to leases, correspondence, contracts, tax returns, reports to government agencies and bank and stock brokerage accounts. Mr. Nader was aware of the fact that I regularly signed his name to these documents and would often specifically request we do so because he did not want his real signature widely known. ... The fact is that I did sign the checks which were in accord with regular practice of payment of legitimate office expenses."

In the affidavit, Jacobs indicated that the reason he decided to leave Nader's employ was his growing concern about the way Nader handled his personal and professional finances. Jacobs outlined in some detail what he characterized as questionable practices regarding taxes, bookkeeping, investments and stock transactions. He wrote, "Although Mr. Nader was earning approximately $500,000 per year in personal income, he paid little or no taxes since he deducted various expenses of his operations as 'business expenses' or he made contributions to 'charitable organizations' controlled by him." Jacobs continued, "He also engaged in what I viewed to be questionable end of year tax juggling, often pre-dating or post-dating checks to get a deduction in a particular year. He would often pad travel expenses and double-bill for travel expenses when he had two engagements in a particular out-of-town city."

The former associate also charged that Nader's nonprofit enterprises were run with very little oversight by their boards: "No independent outside audits were made of any of the Nader organizations until various states required Public Citizen statements."

Jacobs also wrote in the affidavit that Nader was "inordinately harsh in his dealings with his employees and others. Although he had amassed a reserve of over $2 million in various foundations, organizations and in his personal brokerage account, he paid extremely low wages and often refused to pay employees and others for work done."

Jacobs never filed his affidavit with the FBI, but some of the allegations it contains were confirmed by two former associates of Nader's on the Congress Project, an ambitious Nader-sponsored undertaking to investigate every single member of Congress up for reelection in 1972. Attempts to verify information about other people mentioned in the affidavit were unsuccessful because they could not be found or were unwilling to comment about events that occurred 30 years ago.

"The bottom line is, my husband knew everything," says Lenore Jacobs about her late husband. "When he died, everything died with him. Every file or notes that he had, Ralph took and would not return. There's no corroborating it because my husband's dead. It was a horrific time in our lives, not to put too fine a point on it."

Whether Jacobs' accusations about Nader's financial dealings were true or just a counterthreat to get Nader to recant his statement remains uncertain. Salon was unable to independently confirm the allegations about legal and financial impropriety. Nader refused to comment for this story, though he was informed about the nature of Jacobs' charges. What is certain is that shortly after Jacobs prepared his affidavit, Nader sent a letter to the FBI retracting what he had said about Jacobs. In a classic nonapology apology, Nader wrote, "This is to inform you that ... all outstanding differences have been settled ... [which] were insignificant in nature. In light of the above, I would now recommend Mr. Jacobs for a position of trust and confidence with the U.S. Government."

But the damage was done. The highly qualified Jacobs didn't get the job with the Senate Select Intelligence Committee, or any other position that required a security clearance. He reluctantly took a job on the staff of Bella Abzug, the late firebrand Democratic congresswoman from New York, and worked on Capitol Hill until he retired in 1994. Jacobs died in 1998 of a neurological disease.

"I believe the way Ted portrays things is accurate," says Nick Zill, a former Nader associate who knew Jacobs when he worked for Nader. "Ted was a straight shooter and not a frivolous person at all. He was very dedicated to Nader's causes." Though Zill didn't know the details of the men's falling out before being shown Jacobs' notes, he says he is not at all surprised by the characterizations of Nader's vindictiveness. Zill and his former wife, Anne Zill, both worked for the Congress Project. The Zills, too, had a bitter parting of ways with Nader.

"While I worked for the Congress Project, I had taken an idea to Nader, the only meeting I ever had with him," says Anne Zill. "He liked my idea about investigating how the media reports on things happening in Congress. So I worked on it during my own time, but I wasn't able to finish it."

Disillusioned by Nader's autocratic management style and with the paltry wages that the Congress Project was paying them -- the couple had three young children who attended a daycare center in Georgetown for the indigent while they worked -- they both decided to leave the project. After Anne left to begin a congressional fellowship, she began getting harassing phone calls from people working for Nader. "I would get phone calls late at night, demanding that I turn over these notes I had taken for this idea. They said I was breaking the law, that I wouldn't get away with this. They said my reputation would suffer." Anne refused to turn over her work, however, based on her belief that the project had been her idea and that she had done it on her own time.

After her fellowship, Anne applied for a job with Stewart Mott, a public-spirited philanthropist who was on President Nixon's enemies list. According to both Anne and Nick Zill, Nader attempted to torpedo her hiring with accusations that she had stolen notes from the Congress Project. She was hired by Mott anyway, and he even threw a party for her at the Kennedy Center. When Nader showed up at the party, Nick was so incensed he threw a glass of water in Nader's face. Thirty-five years later, Anne still works for the Stewart Mott Charitable Trust.

Nader "dealt very hierarchically with people through his underlings," says Anne Zill. "At any point, if he had asked me about the notes rather than sending his underlings to come get them, I would have talked with him about it."

"He demanded a kind of loyalty that we found disturbing," says Nick Zill. "Anytime he was going to come into the office, it was like the prophet Mohammed was going to appear. There was this blind obedience that we found cultlike. I think the real reason [Nader told Mott not to hire Anne] was that Stewart was an important source of funds for Nader, and he wanted someone more loyal to him in this position. This nominal dispute over notes is very similar to the Ted Jacobs situation."

While Jacobs may have been damaged more than anyone else by Nader, he was by no means the last intimate associate to suffer Nader's wrath. "These weren't just marginal people who he disagreed with," says Toby Moffett, a former Democratic congressman and another early and close associate of Nader's. "These are people who would have fallen on a sword for him."

Like Nader, Moffett grew up in Connecticut. Their fathers, both Lebanese immigrants, were good friends. When Moffett finished graduate school, his father urged him to get in touch with Nader, who was already a national icon. To Moffett's surprise, not only did Nader take his call, but he asked him to return to Connecticut and start an organization that would later become the model for Citizen Action groups around the country. "I saw a lot of Ralph because he would come back to visit his parents [in Connecticut]. I would stay and eat with the family. To me he was a gigantic hero."

After working closely with the old family friend, Moffett ran for Congress from Connecticut in 1974 and won. "Three months after I was elected, [Nader] attacked me," says Moffett. "So our relationship began to sour pretty quickly."

According to Moffett, Nader launched the first of numerous attacks against him over an aircraft noise reduction bill. While the bill stipulated that noise reduction measures would be funded mostly by the airlines, they were also to be subsidized by a tax on airplane travelers -- not the general public -- which Nader dismissed as a corporate handout. Moffett, along with nearly every environmental group, supported the bill. "It was an important piece of legislation that was supported by a coalition of progressive members of Congress, and it passed. Of course, now the Bush administration is tearing it apart."

Nader continued to criticize Moffett during his four terms in Congress, which was disturbing enough, but as with Al Gore, Nader would eventually play a crucial part in ending Moffett's career in elective office. After a fourth term in the House, Moffett ran for the Senate against Lowell Weicker, a Republican, in 1982. "My opponent was running these ads attacking me; the [National Rifle Association] was hammering me from the right," says Moffett. "And then Ralph Nader came up [to Connecticut] and endorsed him. I lost by a very slim margin. My family and I, and my supporters, we just had this blind rage and fury about it. So what he did in 2000 was no shock to me. And what he's doing now is no shock. It's always been about him and his ego."

"He has no interest in being a constructive part of anything," continues Moffett. "No one can name a coalition he has been in where he really rolled his sleeves up and tried to get [something] done. He's shown no interest in anything that could be construed as incremental change. [But] he has had success in empowering people, like Joan Claybrook and others. That's the legacy."

Claybrook is the president of Public Citizen, an organization that Nader founded in 1971. After Ted Jacobs left his position with Nader, Claybrook took over as Nader's right-hand person, and she remained his closest associate until she was appointed by President Carter to head the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which was created in the wake of Nader's auto safety campaign of the 1960s.

Within months of her appointment to the government agency, Nader attacked Claybrook. According to a biography of Nader by Justin Martin, "Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon," Nader wrote a vitriolic 11-page, single-spaced letter that was ostensibly addressed to Claybrook but was in fact distributed widely to the media; Claybrook herself didn't even get a copy.

The letter, parts of which were published in the Washington Post, complained about delays in air bag safety regulation, certainly a legitimate concern. However, Nader went on to berate her for what he perceived as her many shortcomings, and even accused her of being more beholden to the auto industry than to consumers. She felt compelled to call a press conference to address the accusations, and Nader showed up and proceeded to badger her.

Claybrook did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Rather than capitalizing on his unparalleled access to the Carter administration through the dozens of Raiders and other allies working for the administration, Nader adopted a harshly adversarial stance. While many activists find it easier to criticize a conservative administration than to work with a sympathetic one, what's different about Nader, observes one of his former supporters (who does not want to be named), is that his righteous view of himself "translates into a deeply pathological approach to targeting his allies."

Of course, his attacks on Claybrook and other progressives during the late 1970s were outlandish. But given the effectiveness of his uncompromising positions up to that point, his behavior was mostly tolerated and sometimes forgiven. In fact, Claybrook eventually went back to work for Nader after leaving the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fast-forward to the Clinton administration, however, and not much had changed. Despite having little influence during the Reagan and Bush I administrations, he picked up where he left off by attacking both people inside the Clinton White House and advocates who were trying to influence its policies.

"We worked with him on [the Clinton] healthcare initiative," recalls a left-leaning activist who now works as a staff member for a Democratic congressman. She asked not to be identified because of Nader's penchant for retribution. "While we didn't necessarily endorse the Clinton plan, we worked hard to make sure it had a single-payer option. Ralph disagreed with us, completely disagreed with us, and spent time attacking us for selling out. It was a very bitter period of time. If you disagreed with him, you could very quickly become a target even if you were fighting for the same thing."

"His organization has always been top-down," she continues. "He has been able to say, 'This is what it should be,' rather than having to be accountable to people who want to move the ball forward without scoring a goal every time. We had to decide how to respond to the Clinton healthcare bill, so we had a meeting and people argued it out and then we arrived at a position. Ralph [just] sat in a room with two people and said, 'This is what we're going to do.'"

"He lobbied me, or maybe I should say threatened me," says a senior official in the Clinton administration, who also asked not to be identified. "That's what he does. He will meet with you, you'll have a nice discussion about a policy issue, and you'll agree on goals and debate the means, and then he'll go out and say you're a traitor, that you're not a real Democrat. He's made a career out of it. It's never constructive, but it gets him lots of attention. The right wing, of course, loves it."

"Ralph in practice has been tougher on his friends than on his enemies," offers another Clinton administration staffer diplomatically, despite having been on the receiving end of Nader's condemnation. "He has seen his role to be the last honest man."

Bill Zimmerman, a political consultant, would probably disagree with the notion that Nader is the last honest man. As someone who has worked in progressive politics in California for the better part of 30 years, he has had numerous dealings with Nader. Indeed, one of Zimmerman's biggest victories came about because of Nader.

In 1988, Zimmerman was part of a coalition that got a pro-consumer initiative on the ballot promising to lower auto insurance rates as well as give California drivers a rebate. Not surprisingly, the insurance industry fought back hard. On Election Day, there were four measures on the ballot claiming to be insurance reform initiatives. Nader endorsed Zimmerman's proposal -- and it squeaked through. "Nader had a huge impact on getting it passed," says Zimmerman. "Ralph has a lot of clout when it comes to distinguishing the genuine article in a crowd of phonies."

But after several years, it became clear to consumer advocates that the measure wasn't delivering on its promises. Zimmerman and the coalition he worked with believed that fees paid to trial attorneys in auto accident lawsuits were a problem. "So we developed a consumer-oriented, no-fault insurance plan and got it on the ballot in 1994. It would have taken the lawyers out of the equation."

"Not only did Nader oppose it," continues Zimmerman, "but he wrote an Op-Ed for the Los Angeles Times calling me and other people 'consumer traitors.' This is typical of how Nader operates. Rather than arguing the merits or revealing his own financial support from trial lawyers, he publicly demonized the people who were advocating for consumers as shills of the industry. We never took a nickel from insurance companies. There was no logical reason for him to oppose it other than to protect his own financial interest."

Zimmerman readily acknowledges Nader's many achievements. But like others who had bitter fallings-out with Nader, he searches for a psychological explanation for Nader's behavior. "In addition to living inside this bubble of fame, he leads a very monastic life. He has no intimate relationships; he lives without emotional ties to other people. As a result, he is isolated from the kinds of things that help people reach emotional maturity. He has childish and narcissistic reactions to things. If he led more of an ordinary life, some of these problems might be mitigated."

In the past, Nader has lamented his isolated existence. "I didn't socialize much in Washington when I was well-known and heavily reported," he told biographer Justin Martin. "I could have easily. I'm really sorry that I didn't do more of that. It was like postponing it: 'I'm busy on this, I'm busy on that.' People loom much bigger now than they did when they were within a phone call. I felt I could always meet with them, so I put it off. That was a mistake."

It seems that the personality traits that have made Nader an effective advocate -- doggedness, indignation and disdain for how he is perceived -- are the same ones that foment disaster when translated into personal relationships and, more important, electoral politics.

Despite having shunned electoral politics for the better part of his career, as his influence waned in the 1990s, Nader began testing the waters. His first run for the presidency came in 1992, when he entered the New Hampshire primary race, garnering only a bit more than 3,000 votes. In 1996, he "stood" for president [Nader's terminology] as the Green Party's candidate, but spent less than $5,000 -- some say to avoid disclosing personal financial information -- and got less than 1 percent of the popular vote.

In 2000, again with the Green Party, he ran a full-fledged campaign, raising and spending money to get on the ballot in all 50 states. He drew huge crowds at places like Madison Square Garden in New York and Key Arena in Seattle. While he assured Democrats that he wouldn't campaign late in the election season in key battleground states, he reneged on that promise, zeroing in on Florida, Oregon and New Hampshire in the last few weeks before the election.

Few analysts predicted just how close the election would be, but a number of people who had worked with Nader over the years feared that his run for president would be disastrous. "When he announced [his candidacy in 2000] at a big gathering in Washington, I was the first person to stand up and say, 'How can you say there's no difference between Democrats and Republicans?'" says Gary Sellers, who was one of the original Raiders. "There was a big hush in the room. He had no response." Nader was the best man at Sellers' wedding; they no longer speak to each other.

Nader's share of the votes was the margin that threw New Hampshire into Bush's column and accounted for the difference in Florida that cast the state into the post-election turmoil that ended only with the 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision in Bush vs. Gore. Nader nearly cost Gore other states as well, especially New Mexico. Every study after the election determined that almost all of Nader's votes would have gone to Gore if Nader hadn't run, but Nader continues to insist that he bore no responsibility.

Nader's justifications for running again are contradictory. One of his arguments is that he'll take more votes away from Bush than from Kerry, an assertion punctured by an analysis of polling data by DontVoteRalph.net. Nader has also said that he would help Kerry get elected. When the two men met on May 19, Nader emerged with Kerry all smiles and chuckles, indicating that he wouldn't campaign in hotly contested states. Then, just a few weeks later, he reversed that decision, saying he might campaign only in swing states. Republicans are reportedly aiding his campaign to get on the ballot in Arizona, and some conservative groups in Oregon that have helped his campaign in hopes of giving an advantage to President Bush were accused Tuesday of violating a federal campaign law that prohibits corporate contributions to presidential candidates.

Not surprisingly, Nader's arguments for running again are being rejected by Democrats and even by the Green Party, which failed to endorse him at its convention in Milwaukee on June 26. Indeed, the Green Party selected David Cobb as its candidate for president largely because he promised to campaign only in safely Republican and Democratic states. On June 22, Nader had a heated exchange with members of the Congressional Black Caucus, according to reporters who overheard people shouting and cursing. After the meeting, from which several people stormed out, Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, told CNN, "This is the most historic election of our lifetime, and it is a life-or-death matter for the vulnerable people we represent. For that reason, we can't sacrifice their vulnerability for the efforts being made by Mr. Nader."

"The reality is, much of the fallout from having George Bush get elected is being dealt with by people other than Ralph Nader," concurs the chief of staff to a Democratic member of Congress. She says that very few members will even meet with Nader anymore. "I don't know what Nader does on these issues in between elections, but we're the ones -- progressive members of Congress and their staffs -- who are concerned about families who can't get visas to come see dying relatives, people being turned away from Pell grants, the war in Iraq. Every day it's something else. We know that if Gore were in the White House, we wouldn't be dealing with this. If we sound bitter, it's because we are."

Nader's many soured relationships have become the backbone of some well-organized challenges to his latest candidacy. United Progressives for Victory, an umbrella group that is trying to bring the various anti-Nader efforts together, is spearheaded by Toby Moffett and Bob Brandon, another early Nader associate. United Progressives for Victory has been formed as a PAC to raise money for advertising and grass-roots outreach, as well as to fund a celebrity bus tour planned for later in the election season.

In addition to legal challenges like the one in Oregon, other groups have emerged to scrutinize Nader's efforts to get on the ballot in swing states. For instance, former organizers for Howard Dean, Wesley Clark and Dick Gephardt have launched TheNaderFactor.com, which aims to persuade younger progressives by, among other tactics, airing television ads that feature former Nader supporters talking about the real differences between Bush and Kerry. "Everyone is working on this," says Gloria Totten of the Progressive Majority, one of the groups involved with United Progressives for Victory.

But no one expects that Nader will actually withdraw from the race -- despite the fact that even among those who maintain cordial relations with him, there isn't one former associate who thinks his campaign is a good idea. "I don't know of a single person who is supporting Nader now," says Don Ross, who worked for Nader years ago as head of a Citizen Action group and is a founding partner of Malkin & Ross, a progressive lobbying firm in Albany, N.Y. "There's no one that I know of walking around with 'Vote Nader' buttons on."

"He has lost credibility and respect, and he stands to lose it completely if takes enough votes away [from Kerry] to reelect Bush," adds Harrison Wellford, the first executive director of the Center for the Study of Responsive Law, who was involved with Nader's Raiders for Gore. He is now working with Nader's Raiders for Kerry, yet another group hoping to persuade people not to vote for Nader. "Passions are extremely intense now. He's taking a much bigger risk this time around. But he's been impervious to this point. It's difficult for him to give up the opportunity that the [presidential] stage gives him. For that reason, he's dead set on going ahead."

Shares