When Sen. Robert Byrd entered Congress, Harry Truman was ending his presidency and America was grappling with the Cold War. Over the next 52 years, the West Virginia Democrat would participate in the great national security debates of the 20th century, from the Vietnam War to the Cuban missile crisis to the Persian Gulf War. And yet Byrd, a former Senate majority leader, says no president has troubled him as much as President Bush has in his march to invade Iraq.

A prominent critic of the Iraq war, Byrd was one of 21 Democratic senators who voted against the October 2002 resolution that authorized the use force to topple Saddam Hussein. But his critique of the White House goes beyond national security to what he considers Bush's contempt for the constitutional balance of powers and his administration's excessive devotion to secrecy. Of the 11 presidents he has served with, Byrd gives Bush the lowest grade -- lower, even, than for President Nixon, who resigned under the threat of impeachment. His dismay with Bush, whom he disdains as a "child of wealth and privilege" who "did not pay his dues" and is thus ill-prepared to lead the world's most powerful country, prompted Byrd to write a new book: "Losing America: Confronting a Reckless and Arrogant Presidency."

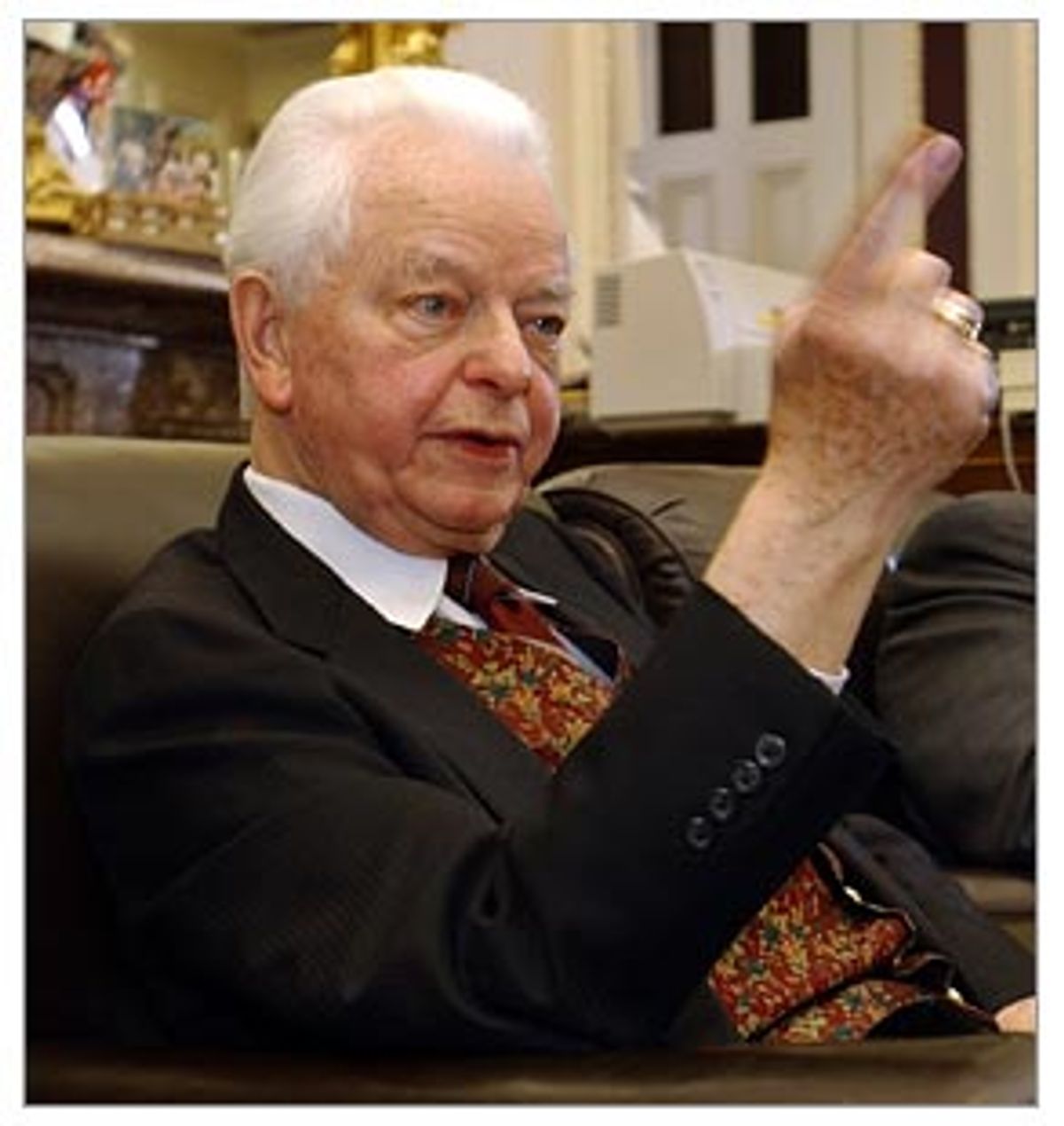

Commanding on the Senate floor, in person Byrd is soft-spoken and charming, almost cuddly, one-on-one. And while he calls Bush arrogant, he can sometimes be equally imperious, especially when dealing with high officials of the executive branch. As a young reporter for the congressional newspaper Roll Call, I interviewed Byrd in 1993 in his grand office suite off the Senate floor. (He then chaired the Senate Appropriations Committee.) An aide interrupted to say that Vice President Al Gore was calling. Byrd waved off the aide and continued his leisurely interview with me about the multivolume history of the Senate he had recently published. After bidding me a gracious goodbye, he took the vice president's call.

An amateur scholar of the ancient Roman Senate and its influence on the framers of the Constitution, Byrd has always been fiercely protective of Congress' constitutional role as a coequal branch of government. In 1993, he delivered a compelling but somewhat eccentric series of 14 speeches linking the fall of the Roman Empire to a then current debate over the "line-item veto," a deficit-fighting tool that was intended to allow presidents to strike individual "pork-barrel" projects from congressionally written spending bills. Byrd argued that such power would allow the executive to blackmail Congress. Although he was unable to block the politically popular line-item-veto law, the courts would later declare it an unconstitutional breach of the separation of powers.

A child of the Depression who grew up in West Virginia's hardscrabble coal-mining country, Byrd's belief in the power of government to improve lives has put him at odds with the modern Republican Party. But while he opposed President Reagan's 1981 tax-cutting package, he says that, unlike Bush, Reagan won fair and square because he allowed full debate, hearings and amendments. Bush, by contrast, rammed through his 2001 tax cuts by having Republican congressional leaders manipulate legislative rules and stiff-arm lawmakers who wanted to offer amendments. The result, Byrd says in his book, is that Bush pushed through a tax bill with disastrous fiscal consequences for the country -- acting as if he'd been elected with a resounding mandate instead of by an evenly and acrimoniously divided public.

At 87, Byrd is still vigorous, proudly noting that he has attended more than 17,000 roll call votes in his career, though he uses a cane and seems increasingly frail. He discussed his new book with Salon in his Capitol office on Wednesday.

In your book, you write that Bush doesn't have the character to run the country, or at least that's the impression I drew. Can you explain?

I'm thinking about the word "character." I would not use that word; it can mean different things. I would say that he wasn't prepared to be president. I would say that he has hurt this country's image, or our character -- I will use the word in this context -- as a nation. Are we honest? Do we use information from the government to the people in a way that twists it differently from reality? He has hurt this nation's character.

I know that he is appealing to various religious groups. That's all right. But the character of this country is not what it was when this administration came to office. Why do I say that? It has misused information. It has acted secretively, time and time again. The White House has tried to operate, and has operated, in a very secretive way. That hurts the character of the country. And this administration, it seems to me, tries to intimidate anybody who criticizes it. I have particularly taken notice of the Senate: It is cowed.

How effective do you believe the Senate Democratic leadership has been in confronting the Bush administration?

It has tried. But I don't think that we can be in session three days a week and be very effective in confronting the administration, as we can be and as we ought to be in this branch of government. We don't ask enough questions. We didn't in the run-up to the war. The Senate was silent. And having come to the Senate when I did, and having seen and heard and worked with the type of senators who were here, when I compare that in my own mind with our virtual cowardice about the war, the buildup to it, I'm very disappointed. I'm chagrined.

Couldn't the Democrats force the Senate to meet more often? Ask more questions? Be more confrontational? Or do Democratic senators, like lawmakers in both parties and chambers, not want to give up their comfortable three-day workweeks?

They have rules in the Senate, and they could ask more questions.

Why don't they?

I wonder myself. In respect to the greatest question that has come before this Senate in my lifetime -- or at least during my career, which extends over a half century -- we failed.

You're talking about the war?

The war, yes. We failed. We relegated ourselves to the sidelines. How many times? How many times did I hear the words [from other senators, privately], "Let's get this thing behind us. Let's talk about something else. It would be better for us in the election if we changed the subject."

This "thing" being the war resolution?

The war resolution, yes. We had our little meetings. We talked about those things very little in the conferences. When it came to the run-up to the war in the last few days, the silence was deadening.

Why?

[Democratic] senators were afraid. Those who were running [for reelection] didn't want to be charged with being unpatriotic -- and they would be. They believed the garbage that was being spewed out by the administration. They believed that Hussein constituted an immediate threat. They were told that there were drones that could be sent over here and used to destroy human life. It was scary, if it were really true.

But then what does it say about the judgment of both John Kerry and John Edwards that they voted for the war?

It says the information on which they based their judgment was false. That's what it says to me. And [the information] has since been shown to be false. Hussein couldn't get a plane off the ground during the war.

But shouldn't they have questioned more vigorously the administration's rationale for the war?

Well, I have no reason to doubt that they did question it. In our conferences, I don't remember any senator who did not question to some degree -- but [it was] not enough. As far as I was concerned, I didn't believe it, and said so at the time. But this administration misled senators and House members. I think the stories this administration told -- I remember the vice president, I believe it was on Aug. 26, 2002, when he spoke before the VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars] national convention, said something like, "Simply stated there is no doubt that Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction." That's the vice president of the United States, and he's saying, "There is no doubt that Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction." And [Defense Secretary Donald] Rumsfeld said, "We know where they are. They're outside Baghdad, in the north, in the east, in the west." Now, that's what I'm sure John Kerry and all the other senators who voted that way [based] their decisions on.

Given that the rationale for war was predicated on lies or untruths, if there had been a Democratic-led House, do you think President Bush would have been impeached? After all, the House impeached President Clinton, even though his conduct had no bearing on national security.

I kind of doubt it. This is not to say that he might not still be impeached. Things are coming to light now that people need to know.

Why do you doubt it?

Everything was caught up in Sept. 11. That has an impact on members of Congress, as it did with everybody else. We immediately went to war, and rightly so, in Afghanistan because we were attacked. Any president in that situation would have acted as Bush did. The country was almost 100 percent behind Bush when he went in to attack the Taliban. There wasn't any chance of Bush's being impeached that early [even if Democrats had run the House].

You mentioned Sept. 11, 2001. You were in your office here in the Capitol that morning. You describe in the book your feeling of being a captain asked to abandon his ship. Can you tell me more about how you felt, knowing that this beautiful building where you've spent your professional life, which has such symbolic resonance for the world, was possibly going to be destroyed in minutes?

I couldn't believe that this majestic edifice was about to be bombed. And the policeman was saying 15 minutes, 10 minutes, eight minutes, whatever. Get out of here! I wanted to stay with the ship. I couldn't believe that I had to get out of this building. But members of my staff insisted that I go. This was a terrible feeling. And so I found my way outside the building, but the staff and policemen were saying, "Go farther." Well, the people who voted on that plane [United Flight 93, which crashed in Pennsylvania] to take things into their own hands, knowing that they were doomed, saved our lives. They saved my life; they saved the lives of many of my staff that day. This building was the target. I didn't get far enough away from it to avoid a direct hit by that kind of missile, a plane loaded with aviation fuel. We're living in eerie times.

Do you believe the Capitol was the intended target that day?

I do. In my mind's eye, I thank those people who died to save this Capitol, my life and my staff. It is a feeling that still haunts me whenever I think about it.

But instead of attacking al-Qaida, the administration turned its energies, after Afghanistan, to Iraq. You said this is the "most arrogant" administration you've ever seen, one that treats the public contemptuously by being secretive, or untruthful, about its motives. Are you saying it is worse than the Nixon administration?

Of course it is. And it has some carryovers from the Nixon administration who are right smack in the middle of the arrogance. Who are they? Well, the vice president was part of the Nixon administration. Mr. [Paul] O'Neill, the former treasury secretary, was part of the Nixon administration. Mr. [Paul] Wolfowitz [deputy secretary of defense] was part of the Nixon administration.

I'm sure you've read "Bush at War" by Bob Woodward. Here is a quote by Bush in the book that I want to read to you. [Byrd picks up a notecard with the quote written on it and speaks as if he were Bush.] "I'm the commander. See? I don't need to explain. I do not need to explain why I say things. That's the interesting thing about being the president. Maybe somebody needs to explain to me why they say something, but I don't feel like I owe anybody an explanation." There's your arrogance supreme.

Why did you write the book?

The first three words of the preamble to the Constitution answer that question. "We the people." It's the people's Constitution. It's the people's government. This administration came to power without the president's having received a majority of the popular vote. He had no mandate. His administration claims a mandate. The people are being misled by this administration. They're being ... well, "cheated" is a pretty strong word, but in some respects, they are being cheated.

When Bush came into office, he had a $3.5 trillion surplus. But what happened to that surplus? He recommended in his first year, right off, that more than $2 trillion go out of this government in tax [cuts] in the first 10 years. And the administration, working with Republicans in Congress, devised the approach of back-loading most of the revenue losses that would come from these tax cuts. That was being dishonest. It's another instance of saying, "Watch my left hand, don't watch my right." We'll put this back over here so it won't be noticed immediately. That was wrong. In other words, a train wreck will happen when Mr. Bush is out of office, not while he's in. That's why I wrote this book. The people are being misled by this administration.

Shares