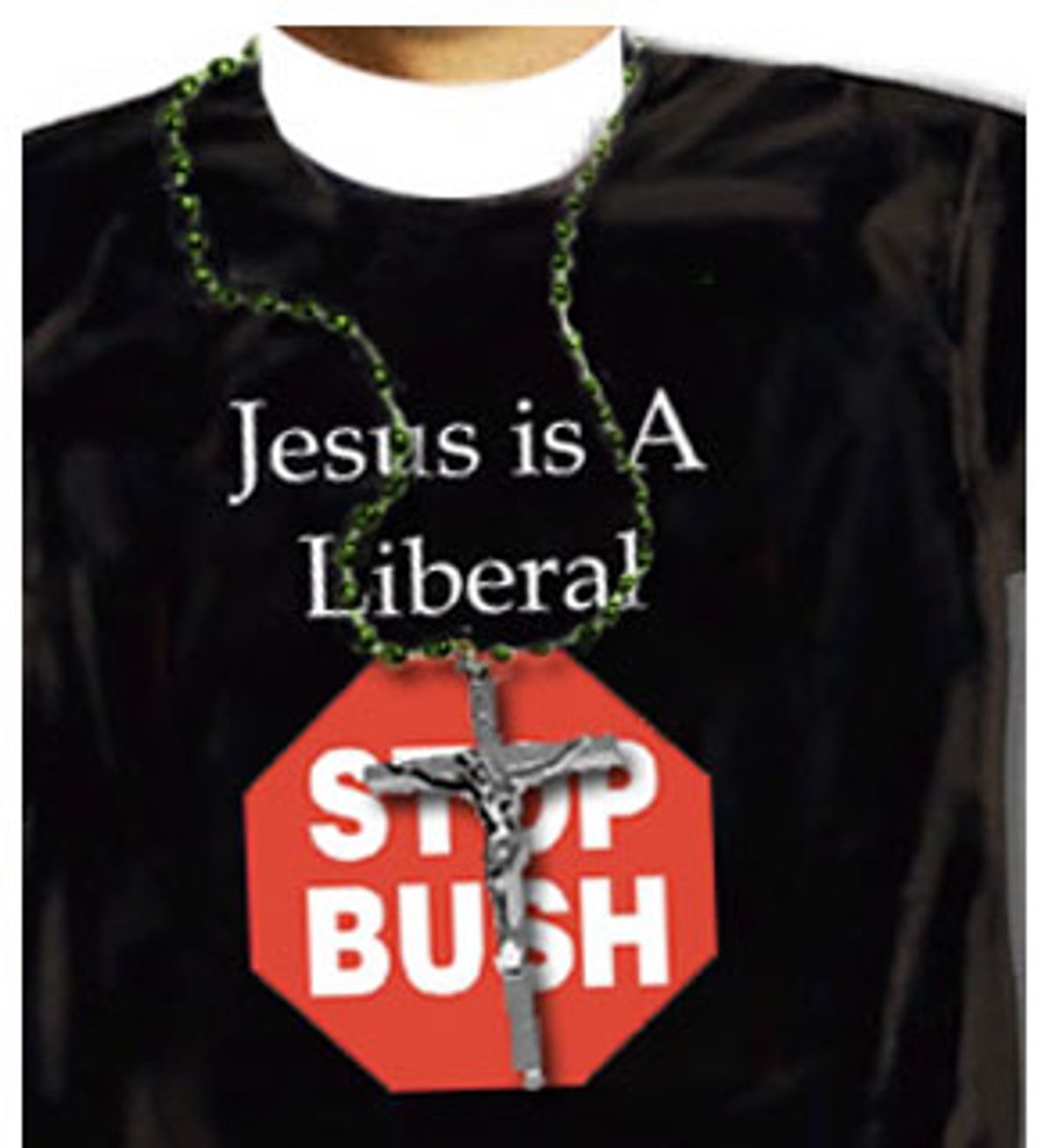

The Bush administration is going to hell. That, at least, could be the take-away message from a Tuesday press conference religious leaders from five major Protestant denominations held at the National Press Club. Clad in clerical collars, and invoking the Gospel story of Lazarus, a poor man ignored at the gate of a rich man's estate who went to heaven while the rich man was sent to hell, the leaders called on Congress to oppose what they called an "immoral budget" and staked a claim for moral values that don't have anything to do with abortion or gay marriage. "The 2006 budget that President Bush has sent to Capitol Hill is unjust," they charged. "It has much for the rich man and little for Lazarus." But while the press conference focused on calling attention to the need for truly compassionate policies that protect the most vulnerable in society, it had another mission as well: to assert the relevance of the religious left.

What's that, you say? The religious what?

Everyone knows about the religious right, a movement of conservative, mostly Christian, religious communities that has become increasingly involved in American politics over the last three decades. The idea that there could be a countervailing religious force, whether defined as religious progressives or simply everyone not part of the religious right, has long since been dismissed from public consciousness. Indeed, the religious left had almost forgotten about itself -- the community hadn't come together to protest a federal budget, one of the religious leaders told me, "since the early Reagan years."

And yet there was a time -- not so very long ago -- when the religious left was a powerful institution in American society and politics, when the term "religious" was not immediately assumed to connote "conservative." Moral giants with names like Reinhold Niebuhr and Dorothy Day and Martin Luther King Jr. led intellectual and social justice movements. It's nearly impossible to page through American history without coming across political causes that were driven either partly or entirely by progressive people of faith -- abolition, women's suffrage, labor reforms of the progressive era, civil rights, and any number of antiwar movements. Just a few decades ago, venerable organizations like the National Council of Churches (NCC) made pronouncements that carried not only moral weight but political influence as well. In short, the likes of Pat Robertson, James Dobson and Ralph Reed have not always dominated American politics; indeed, in the span of American history, the last three decades are an anomaly.

Today, the religious right and the Republican Party are clasped in a mutually beneficial relationship while the religious left and the Democratic Party are barely on speaking terms. Last year was the best in recent memory for cooperation between the two camps, and yet there is no question that relations are still dangerously strained. While the Kerry campaign hired several individuals to coordinate religious outreach -- the first time a Democratic presidential campaign has branched beyond outreach to black churches -- they were not held in high regard; the campaign's director of community outreach often mockingly referred to her religious colleagues as "the Romper Room," and the communications team simply refused to return press calls on religious issues.

For its part, although the religious left engaged in voter registration and education efforts, held bus tours, and ran newspaper ads, parts of the community remain stubbornly irrelevant. On Nov. 1, the day before the presidential election, the NCC sent out a press release on a matter of great importance to the organization: the treatment of Chinese Uighur Muslim prisoners in Guantánamo Bay. The release -- at a time when conservative evangelicals were mobilizing to increase their voting numbers by 4 million over 2000 and deliver the election to George W. Bush -- simply underscored how far the religious left has fallen from its days of national prominence.

The decline and fall of the religious left has been so complete that news organizations regularly conflate terms like "religious voters" and "moral values" with "right-wing," without a second thought. When Time magazine recently ran an article about Democratic religious outreach efforts, the piece concluded with the thought, "Religious voters might like the music, but they're unlikely to be seduced by it as long as Democrats stick to their core positions," as if religious Americans could only support the Democratic Party by putting their faith aside, not because of their faith. The easiest way to change this perception is for the religious left to aggressively and vocally reenter political life. But it's a long climb back to relevance.

The religious left is responsible, in part, for the religious right's swift rise to power during the 1970s and '80s. For most of American history, conservative Christians had focused primarily on the effort to save souls, making a principled decision to stay out of the realm of politics. "Preachers are not called upon to be politicians," the Rev. Jerry Falwell explained in 1965, "but soul winners. Nowhere are we commissioned to reform externals." At a crucial point in American history, however, a perfect storm developed that changed the political landscape forever, catapulting religious conservatives into political activism.

A series of Supreme Court decisions taking prayer and Bible reading out of schools, and culminating with Roe vs. Wade -- as well as, it must be noted, some civil rights victories in the South -- angered conservative evangelicals, and convinced them that government would not remain neutral, allowing them to simply live as they wished. Similarly, many Catholics -- who had largely stayed away from politics while assimilating amid anti-Catholicism -- were outraged by the Roe decision, and they developed into a politically active force, forming pro-life groups organized not by diocese but by congressional district. Both of these groups were embraced by Republican strategists desperate to form a political majority, who recognized that they could find common ground in the belief that government should stay out of their lives. It was a match made in heaven.

At the very same time, instead of sticking around to act as a check on this budding conservative movement, the religious left effectively disappeared, allowing the rise of the religious right to take place unabated. When they looked around them, the folks on the left considered their work done. The civil rights movement had been their crowning achievement, establishing once and for all the power of moral arguments to bring about political and social change, and the same Supreme Court decisions that had outraged conservatives convinced many religious liberals that they had won the debate: Religion and politics were both best served when religious leaders and communities were independent, when the state did not appear to be sponsoring and controlling religion. Confident that the judicial system was on its side and would maintain this status quo, the religious left took a much-planned and oft-postponed vacation.

The debate, however, was not over; it was simply shifting to a different arena, out of the court of law and into the court of public opinion.

"If there is such a thing as the liberal church anymore," says the Rt. Rev. John Chane, Bishop of the Diocese of Washington, "it has become complacent. Complacency was always its biggest tragedy." While their conservative counterparts were setting aside differences to focus on a single mission, members of the religious left -- no longer following the guiding cause of civil rights -- lost their way, dispersing their attention over what seemed like 87 different policy issues and busying themselves with internal denominational battles over female ordination and other debates. Many well-intentioned members of the religious left, not wanting to be associated with the nascent Christian right, filtered religion out of their rhetoric and secularized some of their appeals. The more vocal groups like the Christian Coalition and Moral Majority became, the more religious liberals withdrew from public view.

The parting gift the religious left gave Christian conservatives was an uncontested public square. Years before the religious right had the membership numbers to match its boasts of political influence, it was winning debates simply by controlling the agenda and cornering the market on religious authority. Richard Parker, who teaches religion and politics at the Kennedy School of Government, believes that the religious left simply forgot about a crucial part of its mission. "The Catholic Church believed it needed to learn how to articulate for its members faith-based reasons for action, and to frame arguments for the public square in ways that did not directly derive from church teaching," he says. "Mainline Protestants [who form the bulk of the religious left] lost the first habit, and only carried out the second." Those members of the religious left that did remain politically active often seemed like caricatures of left-wing activists, agitating to save baby seals, Arctic wildlife, third-world orphans with only the faintest of biblical appeals marshaled on their behalf. While religious groups were some of the most vocal opponents of the recent war in Iraq, their unique voices got lost within a sea of peace slogans. More damningly, to the extent that the religious left continued to exist, it became tied in the public's mind with secularists. "The positions of the religious left and secularists on crucial questions seem indistinguishable," says Joseph Loconte of the Heritage Foundation. "And that hurts them politically."

Religious conservatives spent the 1980s and '90s building national organizations, establishing political action committees, training grass-roots activists, electing school board members in local campaigns, educating young conservatives at seminaries and elite universities, lobbying for judicial appointments, and developing media savvy. To see the fruits of their labor, you only have to look around the nation's capital today. The Department of Justice is staffed by lawyers whose legal credentials are impeccable but whose religious backgrounds would have led them down very different career paths just a few decades ago. The White House boasts a stable of speechwriters with the ability to weave religious language into presidential addresses. And when you tune in to a political talk show, you're likely to find a leader of the religious right adhering to talking points about the ways in which religious Americans have been discriminated against in recent years.

The religious left, on the other hand, hasn't seen any need to build separate institutions because its members already have outlets for political involvement. The average religious liberal doesn't need to go to church to get involved with political issues; she goes down the street to her local ACLU's meeting or to a MeetUp or joins a letter-writing campaign through her teacher's union. Her commitment to politics may be driven by her religious beliefs, but the connection is never made explicit. A religious conservative, on the other hand, spends more of his time at his local church and is more naturally drawn to activism through that community of congregants.

But the religious left hasn't just failed to keep up with conservative institution-building efforts. Financial and other scandals have weakened some existing religious left organizations -- such as the once-powerful National Council of Churches -- which are now so hamstrung that they lack the ability to offer much guidance to religious progressives in the pews. A few ego-driven leaders, concerned that someone else might become the movement's visible spokesperson, have insisted on coalition efforts and joint statements that, while demonstrating the breadth of support, make decision-making virtually impossible and ensure that no one emerges as a spokesperson. In a media world defined by partisans of the religious right, liberal religious spokesmen are loath to "spin" their beliefs and positions, taking principled stands that nonetheless leave television producers underwhelmed and frustrated.

The Democratic Party hasn't helped matters. For years, the party has ghettoized religion -- flooding into black churches on the Sundays before elections, but treating religion as simply a quaint ethnic characteristic -- and the last election was no exception. The Kerry campaign ran just one television ad that mentioned its candidate's background as an altar boy: It was in Spanish, appearing only on a Spanish-language network. And when the candidate spoke about faith (which he often did, charging that Bush was a "man [who] claims to have faith, but has no deeds"), it was almost always in front of an African-American audience, fueling charges that Kerry's faith was insincere and brought out only for political purposes. No one has argued that Democratic politicians should suffuse their rhetoric with hymn lyrics and claim God's endorsement. But by backing away from each other like opposing magnets, the religious left and the Democratic Party have ceded the language of faith and values and morality to conservatives.

There are signs of hope. After the election, the religious left commissioned and received a report that brutally, but accurately, assessed the movement's weaknesses and past mistakes. Jim Wallis, founder of Sojourners magazine and the progressive Call to Renewal organization, has a new book on the New York Times bestseller list and has been blanketing airwaves on a national book tour, chatting up Jon Stewart, Charlie Rose and Terry Gross. And millions of Americans, outraged by post-election assumptions that "moral issues" are defined exclusively as conservative concerns, are hungry for a way to mobilize their religious progressive numbers. They may have to go hungry a while longer. When I asked the assembled leaders how they planned to mobilize their congregants to oppose the Bush budget, the response was meek: "We have some listservs ... we're asking people to contact their representatives." After an election season in which the Christian Coalition distributed 70 million voter guides, the religious left will need to do more to make itself heard.

Shares