Willie Searcy never got to meet Priscilla Owen. And that's unfortunate. Because as an associate justice on the Texas Supreme Court, Owen once exercised almost complete control over the fate of the working-class kid who always played above his weight on the local rec-league football team -- until the car accident that changed his life and crossed his path with Owen's. The account of Willie Searcy's experience with the Texas high court provides real insight into what sort of federal appeals court judge Owen will be if the Senate approves her lifetime nomination to the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals. But Searcy's story has been largely overlooked.

Next week, Majority Leader Bill Frist may call up Owen's nomination for Senate consideration, a move expected to spark the long-awaited showdown over the so-called nuclear option. Owen's Democratic opponents, who have blocked her nomination since 2001, have been focused on her creative attempts to restrict abortion rights for minors in Texas. That also goes for the extreme Christian right, which considers Owen's "pro-life" record a justification for its campaign to persuade the Republican majority in the U.S. Senate to eliminate the filibuster rule and confirm Owen. Yet the case that pitted the skinny black kid from Dallas against Ford Motor Co. is as important as Owen's attempt to rewrite the law the Texas Legislature enacted to define a specific process by which minors could get abortions. (Not, as Owen held, to make such abortions almost impossible to obtain.)

Willie Searcy's trip to the Texas Supreme Court began in the rain on a Dallas freeway. He was 14 years old in April 1993 when a Mercury Cougar driven by a 17-year-old hydroplaned across the median and slammed into the Ford pickup driven by Willie's stepfather, Ken Miles. Miles' life was saved by the steering wheel, which absorbed some of the impact of the head-on collision. Willie's 12-year-old brother, Jermaine, was saved by a snug seatbelt that held him securely in the middle seat. Willie was not so fortunate. Just before the crash, he leaned forward to pick a piece of paper off the floor. The tension eliminator, which allows the seatbelt to spool out when a passenger leans forward, then retracts the slack and holds the belt in place when the passenger is sitting upright, apparently failed.

Willie Searcy had no broken bones. But the posterior ligaments that held his head in alignment with his spinal cord were torn and stretched. He would spend the rest of his life as a "ventilator-dependent quadriplegic." After being airlifted off the freeway, he spent three months in Methodist Hospital in Dallas and three more months in a private rehab facility. Within six months, Willie's mother Susan Miles and her husband Ken were looking at $550,000 in medical bills. The rest of their lives, in fact, would be defined by medical bills. Their teenage son would require full-time nursing care. He would have to be "coughed" by an attendant. His trachea tube would have to be regularly suctioned to allow a clear path for the ventilator to breathe for him. Every bodily function would be regulated or performed by a machine, relative, nurse, or attendant. It was far beyond what Ken, a parts clerk at a Ford dealership, or Susan, a medical records clerk, could expect from their healthcare coverage.

Willie's attorney, Jack Ayres, wanted to get the case to trial as fast as possible. He believed that a defective part with a history of failure had caused Willie's near-fatal impact with the dashboard, and he set out to sue Ford. Until the tort reform law that Gov. George W. Bush pushed through the Legislature in 1995, plaintiffs in Texas could file suit either where the cause of the lawsuit took place or in any county where the defendant did business. Ford would have preferred to defend itself in Dallas, where conservative judges and juries are friendlier to corporate defendants. Ayres filed in state district court in Henderson, a small East Texas town where there was a Ford dealership. The docket was shorter there, which ensured a faster trial date. The jury pool was probably more favorable to his client. And the state law allowed him a choice of forum.

"We were in a race to save this kid's life," Ayres said.

Cases like Willie Searcy's involve a lot of discovery, hundreds of hours of depositions, hundreds of thousands of pieces of documentary evidence, and countless pretrial motions. They are slow by nature and defendants often try to make them slower, hoping to exhaust the resources of the plaintiff's lawyers, who bear all costs until there is a judgment or settlement. It was not surprising that Ford moved for more time after the judge set the trial for January 1995. What was surprising was what followed after the judge denied Ford's request.

From out of nowhere or, more precisely, from out of the Texas prison system, Willie's estranged biological father intervened and asked for time to allow him to prepare for the case. Willie's attorneys wondered if Ford's defense team had contacted him in an attempt to slow the proceedings. But lawyers on Ford's defense team insisted they had nothing to do with the father's request. Visitor logs at the prison where the father was incarcerated suggested otherwise. Margaret Keliher, a lawyer on Ford's defense team who was later elected Dallas County judge, had visited the prison. Four years later, while working on a book, I asked her if she had gone to the prison to bring Willie's father into the case. She told me that a lot of time had passed and the question -- whether, as a corporate defense attorney, she had traveled to East Texas to meet with a convicted criminal -- was taxing her memory. When Willie's lawyers warned his father that intervention in the case would delay his son's trial, he withdrew.

Ford is always a dogged defendant. One of its in-house lawyers explained the company's litigation strategy to the National Law Journal. Ford would make only one pretrial offer. "I don't give a shit if they take it or not," Ford lawyer James A. Brown told the Journal. "If the plaintiff doesn't settle, it doesn't matter to us. We tell them 'we're coming after you.'"

At the end of the four-month trial, an East Texas jury took only four hours to award Willie Searcy $30 million. On the following day, it met for 90 minutes and awarded the Searcy family an additional $10 million in punitive damages. Jack Ayres had asked for $26 million.

Predictably, Ford came after Willie Searcy and his lawyers. The company appealed both the jury decision and Ayres' filing of his pre-appeal motions in what they claimed was the wrong appeals court. Willie Searcy lost another year, getting none of his jury award. What was finally ruled to be the appropriate appeals court overturned the $10 million in punitive damages and raised one legal question about the $30 million award, which it allowed to stand.

Ford's legal team then took the $30 million in actual damages to the Texas Supreme Court. But the attorneys were decent enough to request an expedited hearing of the case. They recognized that Willie Searcy was kept alive by a patched-together system involving state caretakers, friends, and family working with him at home. There was no backup ventilator or generator to cover a temporary power failure. On paper, Willie was a millionaire, with a jury award that would have provided first-class healthcare. At home in a Dallas suburb, he lived in healthcare limbo.

On the Texas Supreme Court, cases are assigned by a blind draw. Justices pick up cards with case names on them and take charge of those cases. One of the cards Priscilla Owen picked up as the court began its 1996 session had "Miles v. Ford" written on it. "That kid's fate was decided when Justice Owen picked that card," said a lawyer who worked at the Supreme Court at the time.

Priscilla Owen was a Karl Rove candidate for the Supreme Court. An oil and gas lawyer from Houston, she had never been a judge when Bush's lifetime political advisor made her the candidate for an open seat in 1994 and helped direct her successful campaign. Republicans were methodically taking state government away from the Democrats, and Rove was the architect of the takeover, recruiting candidates for statewide office and directing their campaigns. Rove had advised the campaigns of every candidate on the Supreme Court (and the governor and both U.S. senators). On the bench, Owen positioned herself to the right of the court's most conservative justice, Nathan Hecht, whom she occasionally dated. They were kept in check (in the courtroom) by a centrist bloc led by Deborah Hankinson, a 1997 Bush appointee whom the Wall Street Journal described as "the rising star on the Texas Supreme Court."

Two years after the lawyers representing Willie Searcy and the lawyers representing Ford had requested an expedited hearing, Owen wrote the majority opinion. A process that could have been completed within months of the oral argument in November 1996 dragged on until Owen completed her opinion in March 1998.

Her opinion was stunning. Not because it ruled against Willie Searcy and his mother, Susan Miles, but because of how it ruled against them. Owens ruled the case would have to be retried in Dallas because it was initially filed in the wrong venue. Yet venue was not among the issues, or "points of error," the court said it would consider two years earlier when it took up the case. "We felt like we got ambushed," said Ayres. A lawyer who had worked at the court at the time agreed: "If venue wasn't in the points of error, it is unusual that the court addressed it. If the justices decide they want the court to address something not in the points of error, they would ask for additional briefing. They send letters to the parties and ask for briefing." There had been no letters and no requests.

Willie Searcy's case was a textbook example of "results oriented" justice that is common in Texas. Often, judges first determine the desired outcome of a case. Then they adapt the facts and the law to make it happen. It was also a glaring example of judicial activism, or making law from the bench, which is anathema to conservative Republicans -- unless it serves their purposes, as it did in the Terri Schiavo case.

These rulings are not entirely informed by the justices' love for certain principles of law. If the Texas Supreme Court is the most business-friendly bench in the nation -- and it is -- it's because corporate interests pay for the justices' election campaigns. Of the $175,328 Owen took in from the Texas defense bar while Willie Searcy's case moved through the courts, she got $20,450 from Baker Botts, the mega-firm run by Bush family consigliere James A. Baker III. Baker Botts was part of Ford's defense team. It was business as usual in Texas, where the defense bar now pours so much money into Supreme Court races that justices would be left sitting in their chambers if they recused themselves from cases in which their big donors are involved.

So Priscilla Owen is the perfect Bush appointee to the appellate bench. If she's not particularly distinguished as a jurist -- and she's not -- she has demonstrated her willingness to creatively interpret the law in service to both the business community and the extreme Christian right.

Owen was creative to the point of deviousness in the Searcy case. Her delay could be explained (at least in part) by the long, detailed opinion she decided to write. Yet the content of that opinion was as stunning as her ruling on a venue issue that hadn't been briefed before the court. While Willie Searcy waited for the money that would provide him adequate healthcare, Owen and her clerks spent months laboring over a precedent-setting opinion for a statute that no longer existed. It had been replaced by the 1995 tort-reform bill Bush pushed through the Legislature.

Why would a justice write a precedent-setting opinion to clear up contradictions in a law that was no longer on the books? "Priscilla Owen poured [Willie Searcy] out," the former court clerk said in the argot of civil litigation. Even Owen's colleagues were remorseful. The day after the court's decision, the entire court issued a rare addendum to the opinion: "[T]hese appeals should have been concluded months ago, we unanimously agree that the parties' request [for an expedited decision] should have been granted." The court had voted 5-4 against Willie Searcy. But it unanimously agreed to apologize for the unconscionable delay.

Ayres began the case again, this time in Dallas. Ruling on a point of law that wasn't raised in the appeals and writing about a statute that no longer existed, Owen had put him there. Ford's second round of procedural appeals finally ran out on June 29, 2001, when the Dallas Court of Appeals handed down a ruling that seemed to guarantee Susan Miles the money she needed to care for her son. The boy -- who had (heroically) graduated from high school, wheeled from class to class by an attendant who monitored the ventilator that kept him breathing and held a transducer to his throat to allow him to "talk" -- was now 21 and living by a system his parents had patched together.

Four days later, on July 3, the patchwork system of care unraveled. Willie's night attendant left at 4 a.m. At 5 a.m. Susan Miles walked into her son's bedroom and immediately realized that something was wrong. The ventilator was not working. "Aged out" of Medicaid at 21, Willie's weekly nursing allotment had been reduced from 104 to 34 hours. His working-class parents didn't have the resources to hire round-the-clock attendants or place him in a facility where he would have round-the-clock monitoring and care. What Jack Ayres had described nine years earlier as "a race to save this kid's life" had become a marathon. But it was over.

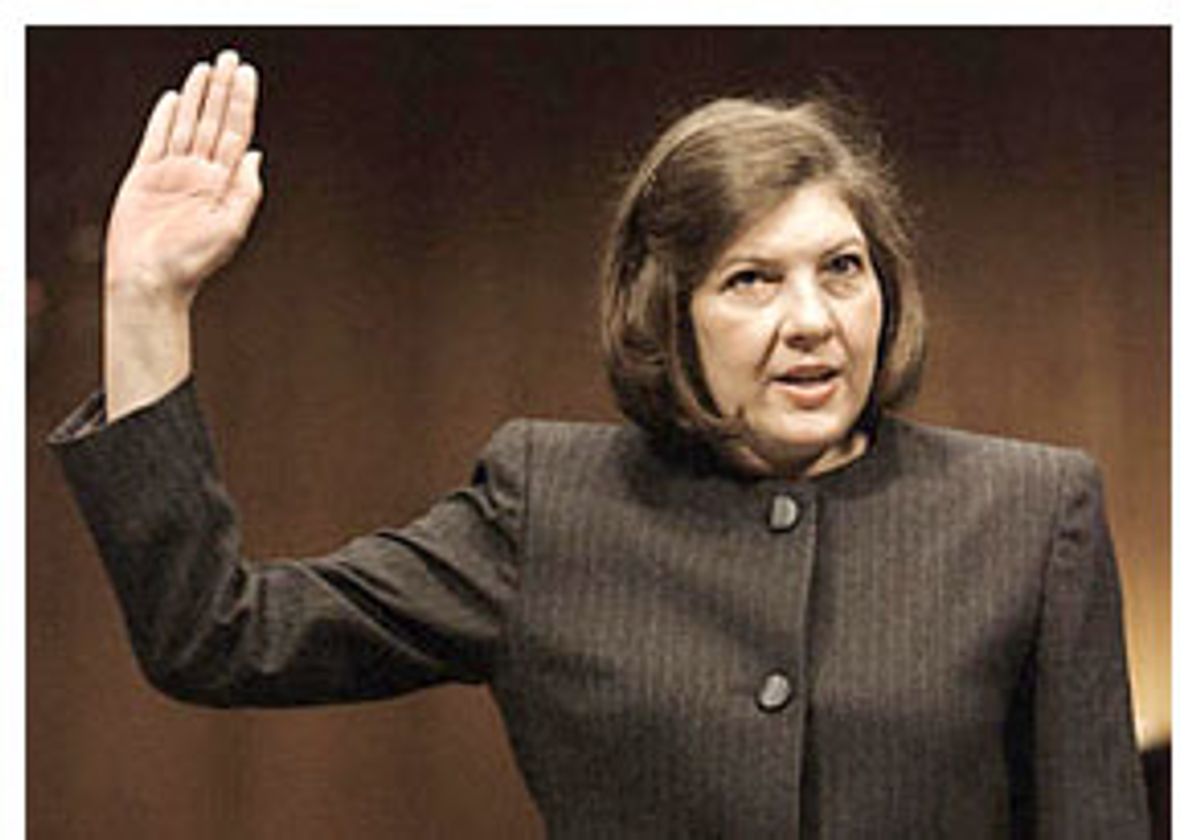

At a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing -- before Owen's appointment was blocked by Democrats the first time around -- Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., asked Owen why the decision took so long while Willie Searcy's life was in peril. Owen's answer was straightforward and, for the record, honest.

"He didn't pass away while his case was before my court," she said.

Shares