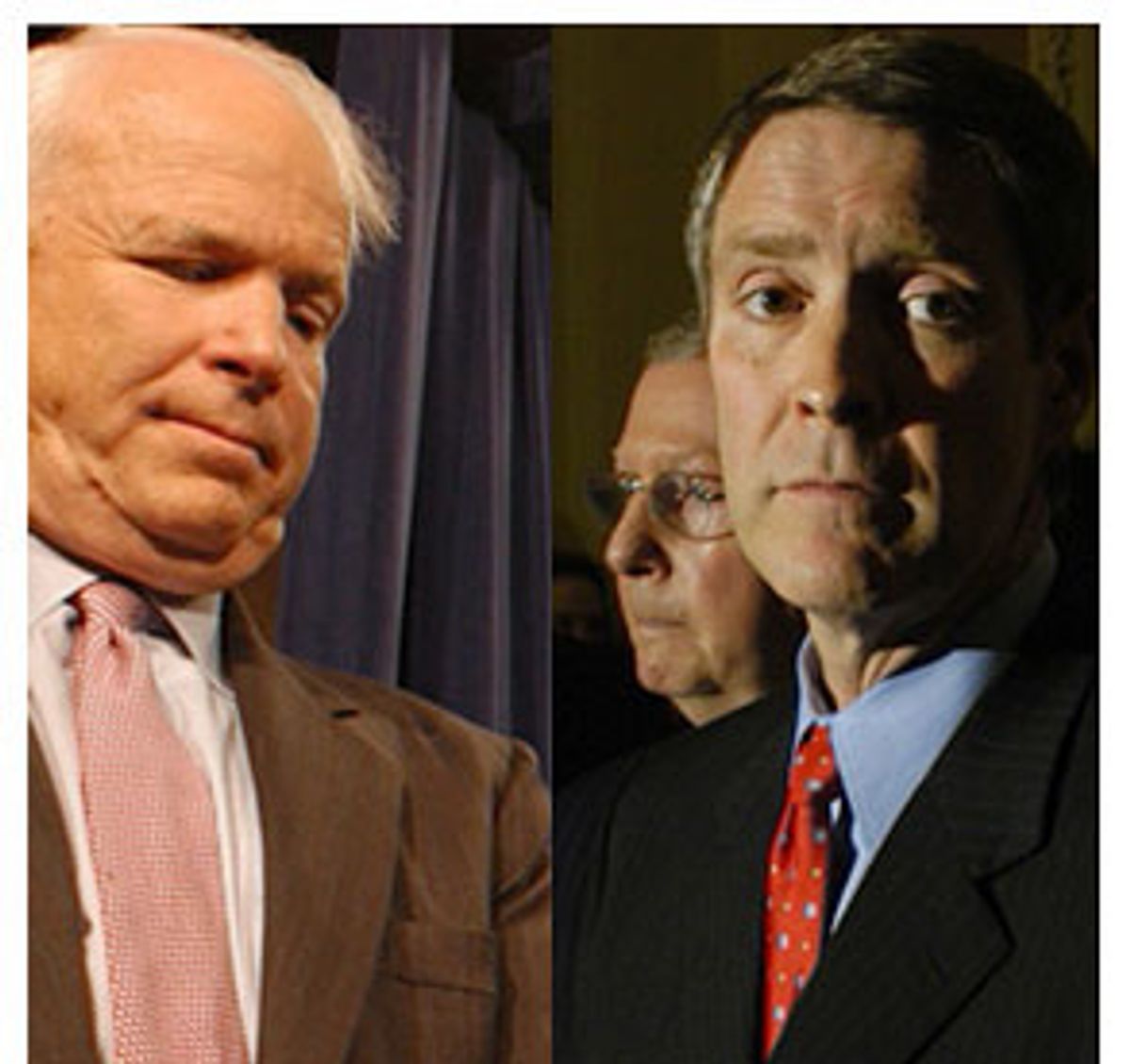

When Sen. John McCain stood before the microphone Monday night and announced the moderates' deal that averted the nuclear option, Majority Leader Bill Frist was nowhere to be found. He wasn't at the press conference. He wasn't a party to the deal. Despite orchestrating the showdown over the filibuster, Frist was left out of the compromise, looking like a fringe player in McCain's show.

If the confrontation over judicial nominees was an early battle among Republicans with an eye on the next presidential election, McCain, a leading centrist candidate, faced off against Frist, who is positioning himself as the conservative's conservative. And by any measure, McCain clearly won. But the filibuster drama may have exposed a larger truth about GOP efforts to succeed George W. Bush in 2008 -- neither McCain nor Frist is well-positioned to win the Republican nomination.

Indeed, the moderates' compromise may serve to undermine both politicians' White House ambitions. It all comes down to the right-wing constituency of the Republican Party. "No one had surfaced as the clear social conservative candidate even before this, and this serves to muddy it up that much more," Republican strategist Ed Goeas said. What's missing from the 2008 candidates, Goeas said, is "a Ronald Reagan conservative."

In failing to kill the filibuster and thus assure the approval of an endless raft of conservative judicial nominees, Frist didn't hand over the goods to the Christian right and may have paved the way for the rise of an even more conservative competitor. "There was only one way for Frist to win in the Republican Party, and that was for him to fully deliver," said Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia. "I was stunned to see the powerlessness projected by Frist and Reid, the majority and minority leaders on the floor [on Monday night]. Neither leader had many followers. They weren't running the show. Now look, you expect that of the minority leader. But you don't expect that of the majority leader. I thought he looked pale and worn and defeated. That is not the profile of a presidential nominee," Sabato said.

As the 2008 race heats up, McCain will undoubtedly reference Monday's compromise as proof that he is the beau ideal of comity, rising above the vitriolic Washington partisanship. But to many in the Republican base, he has never been a greater liability. In stopping Frist, McCain upset the very base he needs to win the Republican nomination. "When you are looking at a primary vote, what Republican primary voters wanted was to get those judges through, and what ultimately occurred is that Frist was pushing for that and McCain stopped that," said Republican strategist David Winston. "He didn't allow that to happen. When you go into the primary process, that's something that people are going to remember. And when you are looking at the Republican nomination, you are going to be looking at a lot more people who wanted all those judges to be accepted."

However Frist went down, he went down fighting for the religious right -- and that could help come primary time. The Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary are won by wooing the more active and more partisan members of each political party. "Of the folks who will attend [the Iowa caucuses] on the Republican side in 2008, you are probably looking at a good third that are active social conservatives," said Peverill Squire, a political scientist at the University of Iowa.

But Frist still has reason to fret. His failure to drop the bomb by triggering the nuclear option, may lead social conservatives to support long-standing conservative presidential hopefuls like Sen. Sam Brownback of Kansas and Sen. George Allen of Virginia. "I don't think [Frist] will get much credit for going down fighting, because it looks as if he lost control of it because there were a group of people negotiating a compromise without him," Squire said. "Frist's problem, potentially, is that he comes off looking opportunistic."

It would not be the first time. Frist's presidential ambitions were marred this March over the Terri Schiavo debacle. Breaking with public opinion, in again attempting to appease social conservatives, Frist tried to usurp the judicial branch and force the courts to reinsert the feeding tube into the brain-damaged Florida woman. Adding ammo to his detractors, Frist said via a recorded message in April, at a rally coined "Justice Sunday," that the senators attempting to block President Bush's judicial appointments were "against people of faith." Frist's rhetoric, and his video appearance at the conservative effort to mobilize Christians around the filibuster fight, prompted Democrats to accuse the majority leader of playing the religion card.

It is a card McCain is least likely to play. The Arizona senator may disdain the "theo-cons'" hold on his party, but if he chooses to run as a Republican it is unlikely he will again declare a frontal assault on the religious right. As a candidate in 2000, McCain said during the primary contest that social conservative icons Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell were "agents of intolerance." Should McCain make one last run for the White House on the GOP ticket, he will likely attempt to compensate for past rhetoric by emphasizing his stance against abortion, while hoping to win with a coalition of independents and Reagan Republicans.

However the judicial battle plays out, Frist will continue to attempt to portray himself as a faith-based option to a McCain candidacy or that of other GOP centrists like Rudolph Giuliani. The majority leader's strategic recourse is political martyrdom, the candidate who went to the brink for the social conservative cause.

After all the spin has been spun, a McCain-Frist face-off may have more to do with the GOP of 2008 than the politicians themselves. Neither candidate owns a room when he steps on the podium. McCain's gravitas and Frist's genial smile notwithstanding, both men can come off stiff. With no heir apparent to President Bush, should the primary contest come down to Frist and McCain, the race will become nothing short of a fight for the soul of the Republican Party. And though McCain would almost certainly fare far better in the general election than Frist, the GOP establishment would be unlikely to back him.

Though McCain is a fiscal conservative and has come out against abortion, his journeys down the political middle have irked the Republican base. Case in point: when McCain joined Sen. Joe Lieberman in supporting legislation that would have closed the "gun-show loophole" for those wanting to skirt background checks when buying guns.

Yet never has McCain's centrism infuriated his party's base more than his refusal to support the nuclear option. Immediately following the Group of 14 compromise, the Republican base was up in arms. Where McCain will likely try to emphasize an outsize role in shaping the bipartisan accord, he will also bear the outsize brunt of the conservative resentment. "It reaffirmed what the Republican activists think about John McCain: He's a maverick, we can't count on him, he undercuts us," Sabato said. "And again, that's not the profile of a Republican presidential nominee."

Shares