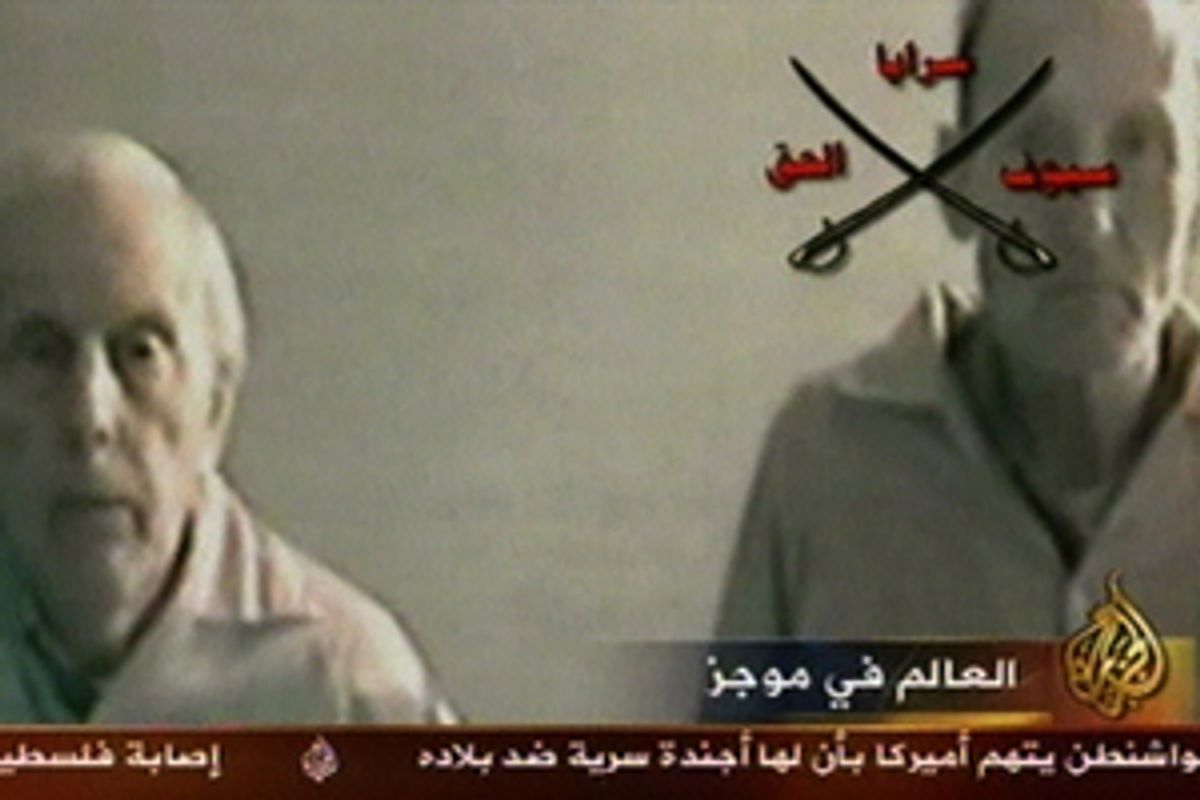

Living in Iraq, Tom Fox wrote of his struggles to transcend rage and fear, to forgive his enemies even as they threatened his life and murdered people around him. Now his faith is being put to the ultimate test. On Nov. 26 in Baghdad, the 54-year-old musician from Virginia and three other volunteers with the pacifist group Christian Peacemaker Teams were kidnapped by a previously unknown band of insurgents calling themselves the Swords of Truth Brigade. This weekend, their captors released a video threatening to execute the four men unless all the prisoners in Iraqi and coalition custody are released by Thursday, Dec. 8.

The grotesque irony is that few have worked as assiduously on behalf of Iraqi detainees as Christian Peacemaker Teams, the last Western human rights organization to operate in Iraq outside the Green Zone. CPT volunteers were among the first to document reports of abuse at Abu Ghraib. Despite the growing danger, they've remained in Iraq to help ordinary Iraqis track down relatives who've been seized by coalition soldiers. Muslim groups throughout Iraq and the Middle East -- including the Iraqi Islamic Party, the country's largest Sunni party, and the Association of Muslim Scholars, a group of prominent Sunni clerics said to have ties to the insurgency -- have called for the Christian Peacemakers' release. But right now, CPT members says none of their contacts know who the Swords of Truth are, or how to reach them.

Ever since he first arrived in Iraq in 2004, Fox has tried to prepare himself for this situation. In October that year, he and 24-year-old Matt Chandler, a recent college graduate from Oregon, were the only two Christian Peacemakers in Baghdad, and they felt the danger of kidnapping increasing. That September, the Italian aid workers Simona Torretta and Simona Pari were abducted and held for three weeks before being released. A few weeks later Margaret Hassan, CARE International's head of operations in Iraq, would be taken, held for a month, and murdered.

Wanting to prepare for the worst, Fox and Chandler drafted a statement outlining their position on their own potential abductions -- a position that begins with empathy for their captors, and a demand that no violence be used to rescue them. Each sent a copy to the members of the five-person support team that all CPT volunteers assemble at home before entering war zones.

Should a volunteer be taken hostage, the statement said, "CPT will attempt to communicate with the hostage takers or their sponsors, and work against journalists' inclinations to vilify and demonize the offenders. We will try to understand the motives for these actions and to articulate them while maintaining a firm stance that such actions are wrong ... We reject the use of violent force to save our lives, should we be kidnapped, held hostage, or caught in the middle of a violent conflict situation. We also reject violence to punish anyone who harms us ... We forgive those who consider us their enemies, therefore any penalty should be in the spirit of restorative justice rather than violent retribution."

There is no reason to believe the insurgents who captured the Christian Peacemakers will be moved by their forgiveness or their frequently stated refusal to dehumanize anyone, even those who would dehumanize them. Margaret Hassan spent 30 years living in Iraq and devoted her life to the welfare of the Iraqi people, but that didn't stop her killers. Innocents and humanitarian workers have been shown no special mercy by terrorists who often appear to have no goal other than spreading chaos and committing mass slaughter.

Fox and his colleagues must have known this -- in their dispatches from the field, a fervent, otherworldly idealism mixes with a sober appraisal of growing danger. But Fox and the other hostages -- James Loney, a 41-year-old from Toronto who serves as program coordinator for CPT Canada; Harmeet Singh Sooden, a 32-year-old electrical engineer from Montreal; and Norman Kember, a 74-year-old retired professor of medical physics from London -- decided to stay in Iraq, anyway. Their choice can seem reckless and crazy, maybe vainglorious, but the fact remains that in a region being flayed by religious and nationalistic hatreds, the members of CPT chose to risk their lives on behalf of human solidarity.

To some, including Fox's daughter, who didn't want him to go to Iraq, the risk wasn't worth it. The Christian Peacemakers' deaths won't change anything in a country coming hideously undone. But in a world torn between competing religious chauvinisms, they are a welcome reminder that deep faith can make people generous rather than punitive, humble instead of jingoistic.

For decades Fox has been to committed to Christianity, which he combines with an expansive interest in other faiths. For him, being in Iraq to witness the devastation and to do his small part to help is a way to take Jesus at his word. He has been scared, but he seems to see his fear as a spiritual obstacle to be overcome.

"It seems easier somehow to confront anger within my heart than it is to confront fear," he wrote on his blog in October 2004, during the spate of kidnappings of aid workers. "But if Jesus and Gandhi are right then I am not to give in to either. I am to stand firm against the kidnapper as I am to stand firm against the soldier. Does that mean I walk into a raging battle to confront the soldiers? Does that mean I walk the streets of Baghdad with a sign saying 'American for the Taking'? No to both counts. But if Jesus and Gandhi are right, then I am asked to risk my life and if I lose it to be as forgiving as they were when murdered by the forces of Satan. I struggle to stand firm but I'm willing to keep working at it."

People involved with Christian Peacemaker Teams are quick to note that thousands of Iraqis have gone through what their friends are going through without garnering international attention. Speaking of Fox, Pearl Hoover, pastor of the Northern Virginia Mennonite Church and a member of Fox's five-person support team, says, "Part of his being there was to be a presence with people at their own level of risk. As I understand it, thousands of people are being held hostage in Iraq. It's just that Tom happens to be connected to the West and the outside world. Who knows what other families are wondering what happened to their loved ones? That's not being covered in international news." Hoover isn't trying to minimize what's happening to Fox; rather, she says, she is asking that the same concern be shown for all the Iraqis who are also in his situation.

After Sept. 11, Fox, who spent two decades as a clarinet player in the Marine Corps Band, yearned to do something different and more meaningful with his life. A Quaker, he was drawn to the CPT's peaceful mission, and though he'd never been to the Middle East, he volunteered to go to Iraq. Hoover says he didn't have a martyr complex or a self-destructive streak -- something she looks out for in people who sign up to put themselves in harm's way.

"For [Fox] it was a very measured approach," she says. "He acknowledged it was a risky thing to do, but he wasn't apologizing for it, and he wasn't saying, 'Bring on the trouble.' He was simply saying, 'I want my life to be meaningful.' And I think that's something that someone who's not mentally balanced would not say. He wasn't looking to die. And that's where his message is completely different than people who choose war or people who choose suicide bombing. He went there because he wanted to look for peace wherever it was and to nurture that peace."

Christian Peacemaker Teams try to create small zones of peace and reconciliation in the midst of war. The organization was founded in 1988 by a coalition of Christian denominations including the Quakers and the Mennonites. Based in Chicago and Toronto, CPT sends trained volunteers to the most dangerous spots on the planet, including Colombia, the West Bank and the Congo, to act as witnesses and advocates for ordinary people caught in violent conflict. They plan projects based on the needs they see on the ground and the voids they believe they can fill. In Iraq, that means working on behalf of detainees in American custody, many of whom, according to military documents obtained by the ACLU, have turned out to be innocent.

As English-speaking Westerners in Iraq, the Christian Peacemakers are able to navigate the occupation bureaucracy better than locals, and they serve as a crucial go-between for families desperate to find imprisoned relatives caught in coalition military sweeps. They live in an unguarded apartment in an ordinary Baghdad neighborhood, where Iraqis can seek them out when they need help.

"They would come and say, 'We don't know where our family members are, we don't have any access to them, we don't know if they need medical attention, we don't know if they have legal support. Can you help us find them?" says Kryss Chupp, CPT's training coordinator in Chicago. "And so CPTers would accompany these families to the different authorities involved to try and gain basic information about where these people were located and get access for the families to their detained family members."

Through that process, Chupp says, "team members began hearing more and more about the kind of abuses that were going on at the hands of coalition forces in U.S.-run prisons." In January 2004, Christian Peacemaker Teams released a report documenting the abuse -- including electrocution, beating and starvation -- suffered by detainees who were later released. When the Abu Ghraib scandal broke four months later, many journalists covering the story cited CPT's work.

The litany of horrors Fox kept hearing -- coupled with all the other torments visited on Iraq -- clearly got to him. On his blog, he wrote about trying not to simply shut down in the face of so much anguish. "The ability to feel the pain of another human being is central to any kind of peace making work," he wrote. "But this compassion is fraught with peril. A person can experience a feeling of being overwhelmed. Or a feeling of rage and desire for revenge. Or a desire to move away from the pain. Or a sense of numbness that can deaden the ability to feel anything at all."

He continued. "How do I stay with the pain and suffering and not be overwhelmed? How do I resist the welling up of rage towards the perpetrators of violence? How do I keep from disconnecting from or becoming numb to the pain? After eight months with CPT, I am no clearer than I [was] when I began. In fact I have to struggle harder and harder each day against my desire to move away or become numb. Simply staying with the pain of others doesn't seem to create any healing or transformation. Yet there seems to be no other first step into the realm of compassion than to not step away."

Fox didn't step away. The day before he was taken, he wrote a brief missive, posted on the Web site Electronic Iraq, titled "Why Are We Here?" He concluded, "We are here to root out all aspects of dehumanization that exists within us. We are here to stand with those being dehumanized by oppressors and stand firm against that dehumanization. We are here to stop people, including ourselves, from dehumanizing any of God's children, no matter how much they dehumanize their own souls."

To outsiders, such faith can seem naive or even foolishly reckless. Rush Limbaugh, for one, was pleased by the Christian Peacemakers' kidnapping, saying, "Well, here's why I like it. I like any time a bunch of leftist feel-good hand-wringers are shown reality."

Fox's son and daughter were clearly unhappy to see their father go to Iraq; his daughter released a brief statement mingling pride, frustration and grief. "My father made a choice to travel to Iraq and listen to those who are not heard," she says. "His belief that peaceful resolutions can be found to every conflict has been tested time and again, but he remains committed to that ideal, heart and soul. This is very difficult for my brother and me. We want to be with our dad again. I didn't want him to go to a country where his American citizenship could potentially overshadow his peaceful reasons for being there. But this is who my father is and I am strengthened by it. I write this with the utmost respect and agreement with what he stands for."

The combination of awe at her father's kindness and frustration at his implacable rejection of political realism is easy to understand. At times, the attempts by members of CPT to avoid demonizing their friends' abductors can be so hard for nonbelievers to grasp that they approach self-parody. I ask Cliff Kindy, a member of Christian Peacemaker Teams' steering committee who has taken three five-month trips to Iraq, what he thinks of his colleagues' kidnappers. He responds that instead of "kidnappers," he prefers the word "hosts."

"If you start using words like 'kidnap' or 'holding for ransom' or 'abducting,' then it begins to depersonalize human beings," he says. "If Tom and Jim [Loney] are 'captives,' you put them in a box. It takes away from their humanity, and also the people who are hosting them. They have family members -- they may be married, they may have children. They are somebody's children. They have dreams and hopes for their country." He's convinced that Fox and Loney, whom he knows well, will be trying to "humanize these other people who are there with them. And maybe that's how changes come. Even if they die, they'll be a spark that brings a change."

This may sound idealized and abstract, but Kindy puts it in practical terms. "Groups all over Iraq, like the Islamic Scholars Board, religious leaders and human rights groups, are speaking out on behalf of these CPTers," he says. "We didn't come into Iraq with armed guards, we don't wear flak jackets, we don't ride in Humvees or tanks. And I think we're alive today because that's how we operated in Iraq. There's no way anybody who is armed could have done the things we've done. We've been in the razor-wire cities. We've been in the homes of Iraqi families in Fallujah, Ramadi, Karbala. Abu Hishma village that was razor-wired for eight months, we slept overnight in that city. People would say, 'Well, that's naive.' In fact, it's realistic. If you're going to run around with guns, you're going to get killed."

Kindy knows pacifism isn't a shield in a war zone. But dying in pursuit of nonviolence is a worthy sacrifice to Christian Peacemakers. Kindy says he suspects and hopes that, whatever happens, Christian Peacemakers will maintain its presence in Iraq. "One of the things we need to learn from the military is that there are risks that are important to take -- risks worth putting our lives on the line for," he says. "If, in our peacemaking, we can't have that same level of commitment, that would be sad."

Shares