Three former college football teammates of Sen. George Allen say that the Virginia Republican repeatedly used an inflammatory racial epithet and demonstrated racist attitudes toward blacks during the early 1970s.

"Allen said he came to Virginia because he wanted to play football in a place where 'blacks knew their place,'" said Dr. Ken Shelton, a white radiologist in North Carolina who played tight end for the University of Virginia football team when Allen was quarterback. "He used the N-word on a regular basis back then."

A second white teammate, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he feared retribution from the Allen campaign, separately claimed that Allen used the word "nigger" to describe blacks. "It was so common with George when he was among his white friends. This is the terminology he used," the teammate said.

A third white teammate contacted separately, who also spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of being attacked by the Virginia senator, said he too remembers Allen using the word "nigger," though he said he could not recall a specific conversation in which Allen used the term. "My impression of him was that he was a racist," the third teammate said.

Shelton also told Salon that the future senator gave him the nickname "Wizard," because he shared a last name with Robert Shelton, who served in the 1960s as the imperial wizard of the United Klans of America, a group affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan. The radiologist said he decided earlier this year that he would go public with his concerns about Allen if a reporter ever called. About four months ago, when he heard that Allen was a possible candidate for president in 2008, Shelton began to write down some of the negative memories of his former teammate. He provided Salon excerpts of those notes last week.

On Sunday morning, Salon spoke with David Snepp, a spokesman for Allen's Senate office, to ask for a response to the recollections of the three former teammates. E-mail and phone messages were also left for Bill Bozin, a spokesman for the Allen campaign, and Dick Wadhams, the campaign manager. Though Snepp indicated that the campaign, and probably Wadhams, would respond, eight hours later no one in the Allen camp had replied to Salon. Chris LaCivita, a consultant to the Allen campaign, hung up when a Salon reporter reached him midafternoon Sunday. Additional attempts to contact the campaign were unsuccessful. (Since Salon published this story, Allen has denied to other reporters having ever made such a racial slur.)

The racial attitudes of Allen, a once formidable presidential contender in 2008, have become an issue in his highly contested reelection campaign against Jim Webb, a former Marine and author. Last month, Allen was videotaped calling an Indian-American college student "macaca," an obscure word for monkey that is also used as a racial epithet in some parts of the world. Allen has since apologized to the student, saying that he made up the word, and did not know its other meanings.

Last week, Allen again created controversy by appearing offended when a reporter asked about the Jewish lineage in his mother's family, which he has since acknowledged. Allen has also faced questions about his affinity for the Confederate flag, which he wore as a pin in a high school yearbook photo and exhibited in his home in Virginia.

In public statements, Allen has said that he realized later in life that the Confederate flag was a symbol of violence for black Americans, and he has expressed some regret. "There are a lot of things that I wish I had learned earlier in life," Allen said in an appearance this month on NBC's "Meet the Press." But Allen has maintained that he never harbored any discriminatory attitudes toward blacks. "Even if your heart is pure, the things you say and do and the symbols you use matter because of how others may take them," he said in the prepared transcript for remarks to a luncheon with black educators on Sept. 13.

Over the past week, Salon has interviewed 19 former teammates and college friends of Allen from the University of Virginia. In addition to the three who said Allen used the word "nigger," two others who were contacted said they remember being bothered by Allen's displaying the Confederate flag in college, but said they do not remember him acting in an overtly racist manner. Seven others said they did not know Allen well outside the football team, but do not remember Allen demonstrating any racist feelings. A separate seven teammates and friends said they knew Allen well and did not believe he held racist views. "I don't believe he was insensitive," said Paul Ryczek, who played center in Allen's year before joining the Atlanta Falcons. "He had no prejudices, biases or anything else."

In the interviews, old teammates generally spoke of him highly, as a good friend, a bright and ambitious student, and a colorful character who embraced Southern culture, listened to country music, and attracted the nickname "Neck," as in redneck. "If a black guy dropped a pass, he would say something to him," said Gerard Mullins, who played defensive back in Allen's year. "If it was a white guy, same thing. It really didn't matter where you were from, who you were, or anything."

The three former teammates, however, painted a very different picture of Allen when he was around his white friends. Shelton said he feels a personal responsibility to tell what he knows about Allen's past, especially now that Allen has been mentioned as a possible presidential candidate. "I got to know Allen a little too well," Shelton said, adding that he does not believe Allen should hold elective office. "He had prejudices that were deep-seated."

Shelton said no political animosity has driven his decision to speak out. He has switched between Democratic and independent registration in recent elections, he said, and does not consider himself politically active. Four years ago, Shelton and his wife donated $1,000 to Sam Neill, the Democratic challenger to Rep. Charles Taylor, R-N.C., because Shelton said they knew Neill and were upset by the allegations of corruption against Taylor, who was reelected. In February, Shelton supported Rick Davis, a current Republican candidate for sheriff, and penned a letter to the editor in the Hendersonville Times-News backing Davis' campaign. Shelton says he does not know much about Allen's political ideology and says he hasn't spoken to him in about 30 years. "There are no personal grudges," Shelton said. "There was no falling out."

Shelton played football with Allen in the 1972 and 1973 seasons, according to the team media guides from those years. Shelton remembers Allen's attitudes about race surfacing early in their relationship. At one point, Shelton says, Allen nicknamed him "Wizard," after United Klans imperial wizard Robert Shelton. "He asked me if I was related at all," Shelton remembers. "I knew of that name, and I said absolutely not." Several former teammates confirmed that Shelton's team nickname was "Wizard," though no one contacted by Salon could confirm firsthand knowledge of the handle's origin. "Everyone called me 'Wizard' that knows me from those days," said Shelton. "My nickname stuck."

Shelton said he also remembers a disturbing deer hunting trip with Allen on land that was owned by the family of Billy Lanahan, a wide receiver on the team. After they had killed a deer, Shelton said he remembers Allen asking Lanahan where the local black residents lived. Shelton said Allen then drove the three of them to that neighborhood with the severed head of the deer. "He proceeded to take the doe's head and stuff it into a mailbox," Shelton said.

Lanahan, a former resident of Richmond, Va., died this year at the age of 53, said his aunt Martha Belle Chisholm of Richmond. In an interview on Thursday, Chisholm said that she remembered Lanahan speaking highly of Allen. "Bill was very complimentary of George Allen," she said. "He said he was just one of the boys." Chisholm also confirmed that the Lanahan family owned hunting land near Bumpass, Va., about 50 miles east of the University of Virginia campus.

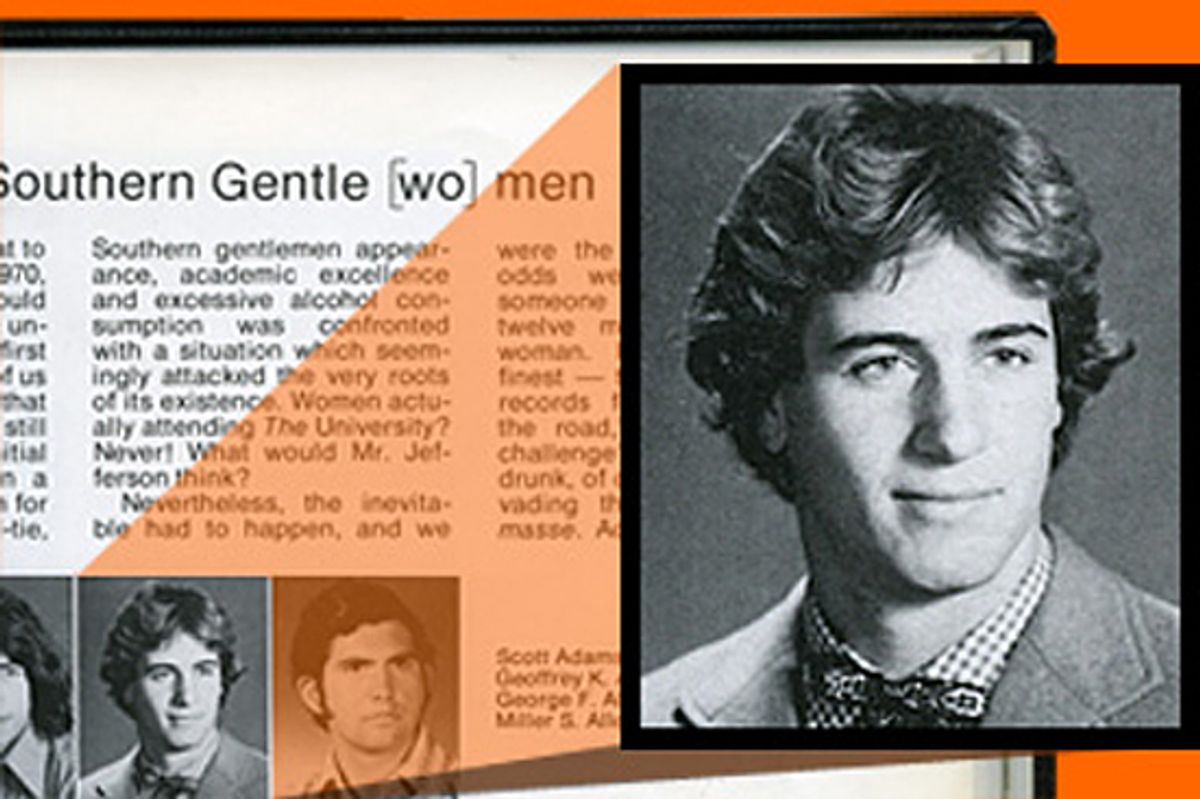

Allen, a college quarterback, arrived at Virginia in 1971 as a sophomore transfer from the University of California at Los Angeles, where he had a football scholarship after graduating from nearby Palos Verdes High School. He relocated to Virginia around the same time that his father, also named George Allen, took a job as the head coach of the Washington Redskins. At the time of his arrival, race relations at the University of Virginia were delicate. Allen's graduating class was the first to offer scholarships to black athletes, and included the first four black players on the football team and the first black starting quarterback, Harrison Davis, who did not return calls from Salon.

Accusations of racial insensitivity have long dogged Allen's political career. As a member of the Virginia Legislature, Allen opposed a state holiday honoring Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. As Virginia's governor, Allen issued a proclamation honoring Confederate History Month that contained no mention of slavery. In recent years, however, Allen has made a point to reach out to minority communities, sponsoring legislation to fund historically black colleges and a resolution to condemn the lynching of blacks in the South. In a New Republic article by Ryan Lizza earlier this year, Allen discussed a "civil rights pilgrimage" he had taken to Birmingham, Ala., in 2003. "I wish I had [gone] sooner," the magazine quotes Allen saying. "I was listening to the old civil-rights movement, the strategies, the foundations, the tactics."

Several of Allen's teammates remember him arriving at the University of Virginia in 1971 with long sandy blond hair and surfer stories of the Pacific Ocean. "He was a Californian," remembers Craig Critchley, a family doctor in Ohio who played linebacker in Allen's year, and did not remember the senator displaying racial views. "It was like, 'Wow, man, yeah.'"

Shelton last remembers speaking with Allen in the mid-1970s, in Charlottesville, when Allen, then in law school, played with Shelton, who was in medical school, in an inter-city football league. For Shelton, the memories of Allen's behavior during his football days raise clear questions about the senator's fitness for office. "I just think that someone who attains that level of higher office needs to have higher standards," Shelton said. "He has deep-seated core values that are hard to reverse despite what he says."

By contrast, Allen has pointed to a different lesson from his days of football playing in recent public statements. On "Meet the Press," he said his football career was an experience that taught him racial tolerance. "I grew up in a football family, as you well know, and my parents and those teams taught me a lot," Allen said on the program. "And one of the things that you learn in football is that you don't care about someone's race or ethnicity or religion."

Shares