On Feb. 6, 2000, the day Hillary Clinton officially announced her bid to become the next senator from New York, her advance team at a venue in suburban Westchester County was supposed to cue up the Billy Joel ballad "New York State of Mind" before she took the stage. Instead, as the crowd waited for Clinton to hit her mark, an aide accidentally broadcast Joel's "Captain Jack," a song about a Long Island drug dealer, complete with references to heroin and masturbation.

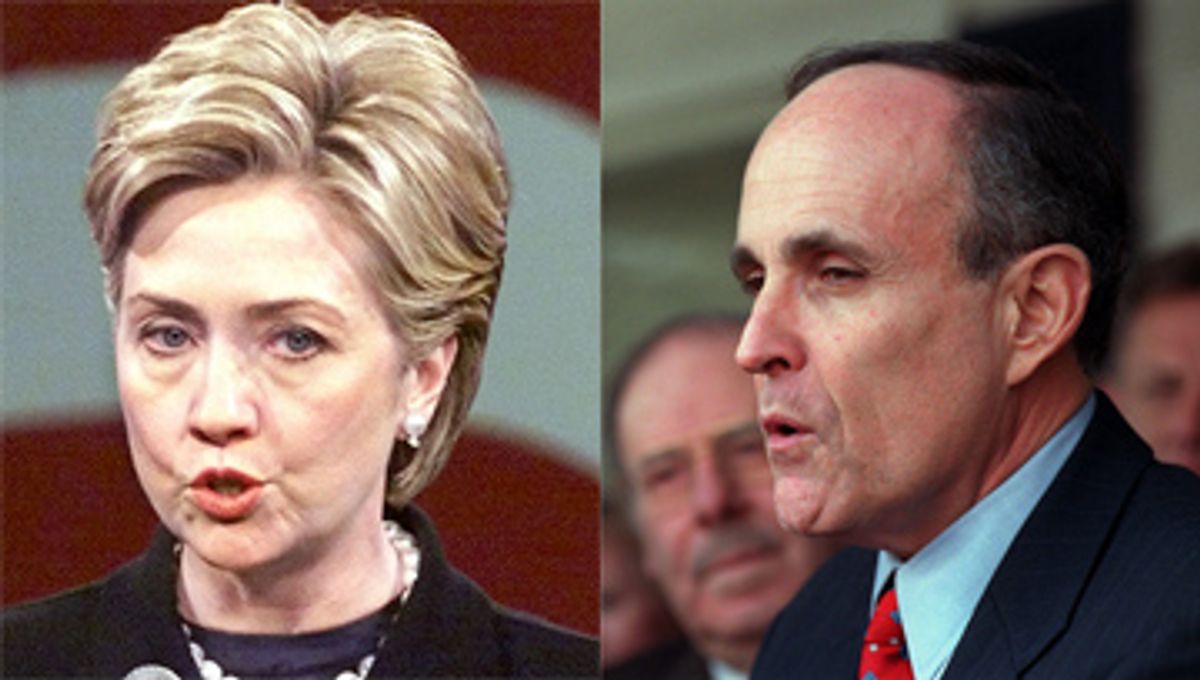

The next morning, Clinton's Republican rival for the Senate seat put her on trial at a press conference in lower Manhattan. Sounding like the federal prosecutor he once was, New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani read aloud a political indictment, the lyrics to "Captain Jack."

"'But Captain Jack will get you high tonight,'" Giuliani recited from a paper in his hand, "'and take you to your special island. Captain Jack will get you by tonight ... just a little push and you'll be smiling.'" Then he raised his eyes to address the assembled media. "I think the message that got out by mistake was, 'Let's say yes to drugs.' I think it's a very, very dangerous message."

Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton had already flown off to Buffalo, where she trudged through the snow and talked about jobs and economic recovery. By that November, Clinton was the senator-elect from New York, and Giuliani's political career seemed all but kaput.

The traditional narrative of the 2000 Senate race, the first time Hillary Clinton and Rudy Giuliani faced each other in an election, is that Giuliani was forced to drop out of the race in May because of the sudden emergence of personal issues. Between prostate cancer and an impending divorce from his second wife, the erstwhile front-runner was, allegedly, no longer a viable candidate.

Perhaps the combination of serious illness and an admitted affair would've been enough, in and of themselves, to sink any candidate's Senate campaign. But in reality, prior to either revelation, Rudy Giuliani was already losing. Hillary Clinton's relentless ground game had slowly eaten away at his lead, but Rudy had done the bulk of the damage himself. In early 2000, polls showed Rudy beating Hillary. Then Hillary began her long march through the snow, and Rudy reminded New York voters again and again what an abrasive figure he could be. The more he made Clinton appear to be a victim, and himself a bully, the better Clinton fared.

Eight years later, the early polling on a potential Rudy-Hillary match-up looks oddly familiar. Would a presidential race between Hillary and Rudy also be a rerun?

The first Rudy-Hillary showdown began to loom in 1998. Giuliani had won a second four years as mayor by a landslide the year before, his last allowable term under law. In the summer of 1998, the mayor, who had seldom left the city during his first term, started hopscotching around the country in what looked like an attempt to burnish his GOP credentials ahead of a run for higher office. There were meetings and photo ops with presidential hopefuls Sen. John McCain of Arizona and Gov. George W. Bush of Texas and with a host of county- and state-level GOP leaders. He apologized for his endorsement of Democrat Mario Cuomo for New York governor in 1994, did imitations from "The Godfather," and regaled GOPers from Pennsylvania to California with jokes about the city he governed -- and Hillary Clinton.

By then there was already speculation that 71-year-old New York Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan would not be seeking another term as senator, and that two of the likely contenders to be his successor were Giuliani and Clinton. Days after the midterm elections of November 1998, Moynihan made his retirement official. Soon the field was cleared for Clinton and Giuliani, though a Long Island congressman named Rick Lazio refused to get the message and continued to believe that he was in contention for the Republican nomination.

From the beginning, the 2000 Senate battle between Giuliani and Clinton had many of the same elements as does the potential 2008 presidential match-up. Clinton would try to protect the Democratic base and swing enough of the narrow band of undecided voters to her side to prevail. Giuliani would start with a decided advantage: Much of the electorate already knew his opponent and disliked her. Hillary Clinton had never even lived in the state she wanted to serve. Giuliani would use Clinton's unpopularity to his benefit and also veer rightward to convince skeptical conservatives that despite his socially liberal record as mayor -- and the fact that his views on many issues were hard to distinguish from Clinton's -- he was still a real Republican. The oddsmakers favored Rudy.

Clinton led Giuliani in polls from late 1998 and early 1999, but by midsummer the two were in a statistical tie. On Tuesday, July 6, 1999, Clinton gave her campaign an unofficial soft launch. She announced that she had formed an exploratory committee for a Senate run. That weekend she began a so-called listening tour of New York state from Dan Moynihan's 900-acre farm in Pindars Corners, a one-traffic-light hamlet 70 miles west of Albany. A sea of news cameras captured the moment as Moynihan christened the launch by walking Clinton to the edge of his property and bidding her good luck. "I think I have some real work to do," Clinton said, "to get out and listen and learn from the people of New York and demonstrate that what I'm for is maybe as important, if not more important, than where I'm from."

Giuliani, meanwhile, hit the ground punching. He made mockery of his opponent a campaign tactic from the start. In June, prior to Clinton's soft launch, he had attended a Chicago Cubs game at Wrigley Field and ridiculed Clinton's recent account of nurturing a longtime affinity for the Yankees despite growing up a Cubs fan in Chicago. In July, a week after Hillary's Pindars Corners photo op, Giuliani trekked to Little Rock, Ark., to raise funds for his own Senate run. From there, he ordered the state flag of Arkansas flown outside New York's City Hall to thank his Republican hosts for their hospitality -- and to tweak the former first lady of Arkansas as a reverse carpetbagger. "Maybe I'll run for governor of Arkansas," Giuliani joked more than once during his Little Rock trip.

Clinton had to establish a residence in New York so she could qualify for the ballot under state law, but she and her husband hadn't even started shopping for a home. They would later move into a $1.5 million Westchester County house. But Hillary Clinton had already ceded the "carpetbagger" argument to Giuliani. At Moynihan's farm she had told the assembled press that the tag was "a fair one." And "carpetbagger" was never a debilitating accusation in New York anyway. Older voters remembered that Robert F. Kennedy had been a "carpetbagger" before beating incumbent Republican Kenneth Keating in 1964 to become the junior senator from New York.

Clinton's Listening Tour would test the political reporters' attention spans and physical endurance as she led them, in slow motion, though all 62 New York counties. The earnest student of the state addressed small groups of voters at each stop about such perennial upstate issues as dairy price supports, air fares, college tuition, and the exodus of college graduates in search of work. She appeared to benefit from low expectations. Just by showing up without horns on her head in the Republican hinterland -- a bona fide national celebrity to boot -- she managed to mollify some voters who had been trained to hate her.

Video: Rudy recites "Captain Jack"

Her opponent was spending his time tacking to the right. In September, Giuliani used his mayoral bully pulpit (and the city's legal department) to attack the Brooklyn Museum for an exhibition featuring a contemporary artist's elephant-dung-dappled painting of the Virgin Mary. In a string of angry photo ops, the mayor termed the exhibition "anti-Catholic" and "sick," stirring protests and counter-protests and fomenting a long-lived media furor. While his patently unconstitutional attempt to punish the museum died in the courts, the controversy was a P.R. boon for a Senate campaign in a state that is 40 percent Catholic.

Giuliani also got some unsolicited help with another major New York constituency in November, when Clinton managed to offend one of the Democratic Party's largest and most reliable voting blocs. The New York Post and other media outlets pounced when Clinton, during a presidential visit to the West Bank, sat in silence as Yasser Arafat's wife accused Israel of causing cancer among Palestinians through the use of toxic gas. Cameras caught the first lady kissing Suha Arafat on both cheeks after the speech. While Clinton rebuked the wife of the Palestinian leader the next day, saying a poor translation had left her unaware of what Mrs. Arafat had really said, many Jewish leaders back in New York sounded less than reassured. Giuliani didn't miss the opportunity to blast Clinton in the media.

Money, too, was easy-come for Giuliani. In January 2000, he sent out an eight-page fundraising letter aimed at conservatives in the American heartland. The handiwork of right-wing direct-mail expert Richard Viguerie, the mayor's solicitation raised the specter of a world where Hillary held sway, inhabited by "liberal judges who have prevented schools from posting the Ten Commandments," by ACLU-countenanced attacks on prayer in schools, and by resistance to the kinds of faith-based social services championed by GOP presidential contender George W. Bush. Giuliani's own words in the letter were measured: "I think America needs more faith and more respect for religious traditions ... not less."

Even eight years ago, when Clinton had yet to hold any elective office, Giuliani was able to raise millions by invoking the possibility of Hillary Clinton in the Oval Office. His candidacy was a sacred cause for out-of-state conservatives who believed that Clinton's Senate campaign was only the test run for a White House bid. Howard Ruff, a Utah financial advisor, formed Ruffpac to solicit donations from Hillary haters nationwide. ("It's a lot easier to kill a 12-inch snake than a 12-foot cobra," he told MSNBC's Chris Matthews during an interview on "Hardball." Matthews, for some reason, responded by helping Ruff hone his rhetoric. "You want to destroy the missile in its silo," said Matthews, "which makes sense to me."). At least 40 percent of Republican campaign funds would come from out-of-state Hillary haters in the 2000 Senate race, helping Giuliani outraise Clinton by 50 percent.

As the new year dawned, Giuliani had become the front-runner. Most polls favored him. In early January, a Marist Poll put him 9 points ahead of Clinton, 49 to 40, and gave him a 61 percent favorability rating. Giuliani also had 42 percent support in New York City, which accounts for about one-third of all statewide votes. The city has long been heavily Democratic, while Republicans, at least eight years ago, could still expect majorities in the suburbs and upstate. But in the city, Giuliani was polling far above the 30 to 35 percent threshold that a Republican for statewide office needed to win. Clinton was on her heels on her party's home turf.

The pundits echoed the polls. "Well, you know what's missing in her campaign?" said Matthews on "Hardball" on Jan. 11, 2000. "I mean, I hate to use the phrase, but there's a phrase like 'white basketball': It's simply going down the court and shooting the basket like a machine. No style, no pizazz, no grace."

"She's had a pretty terrible six months from the time she started coming into the state in July [1999] through the end of the year," agreed liberal journalist Michael Tomasky, then at New York magazine. On the same "Hardball" segment, Fred Dicker of the conservative New York Post dismissed Clinton's chances: "She's in a mode now where she's merely reinforcing already existing prejudgments." Dicker said he thought Giuliani's position was even stronger than the polls indicated.

Still, as Tomasky noted, the numbers had stopped moving in Giuliani's direction. The race seemed to be frozen as solid as the upstate terrain. Then, slowly, the race begin to shift.

Post 9/11, it may be hard for many outside New York to remember that city residents had started to tire of their mayor by 2000, as the end of Giuliani's second term neared. Giuliani's habit of hurling poison darts at Clinton was a reminder to New Yorkers of his appetite for confrontation and his need to belittle opponents. The Clinton operation stuck doggedly to discussing local issues at one campaign stop after another. Hillary would make 30 dutiful visits upstate between July 1999 and mid-February 2000. Giuliani trekked upstate much less frequently, and usually confined himself to city-centered themes and his mayoral record on crime and welfare cuts. The mayor also continued to paint Clinton as a panderer and part of the "liberal elite."

But all of his potshots failed to make a dent in the 10 percent sliver of undecided voters on which the outcome of the election appeared to depend. By January it was clear that Rudy's upstate advertising had not driven Hillary's numbers down or his own numbers up, and polls showed that the carpetbagger charge, never very wounding, had lost much of its power. Clinton ground out yardage little by little and hoped Rudy would beat himself by being, well, himself.

That's what Giuliani was doing on Feb. 7, when he read the lyrics to "Captain Jack" aloud at City Hall. If it was not the turning point in the campaign -- and perhaps it was, because Hillary would pull even with Rudy in some polls within three weeks -- it was at least emblematic of what the coming months would bring.

After Hillary's campaign officially launched on Feb. 6 with its embarrassing, but trivial, musical gaffe, Matt Drudge linked to her use of "Captain Jack" on his Web site. Giuliani operatives contacted reporters early the next morning, telling them to look at Drudge's site, and faxing them an outraged press release from William Donohue of the right-wing Catholic League. Reporters were prepped to ask Giuliani about the Billy Joel song.

At his City Hall press conference, after reading the lyrics aloud, Giuliani professed outrage. "Can you imagine," he asked, "if George Bush had held an event and right before the event a song was played that said, Let's say yes to drugs, let's glorify drugs, let's glorify pot?" He said there was a possibility the choice of songs had been intentional and wasn't just the product of a snafu. "It means that people of that ilk and that ideology are around you."

But the response to Giuliani's gambit, at least in New York City, might not have been what the candidate desired. On the local NBC TV affiliate, political reporter Jay DeDapper betrayed disdain as he explained how the Giuliani campaign had contacted local journalists, trying to interest them in the supposed controversy. "It's only February and it's come to this," said DeDapper, on air. At the end of the week, Daily News columnist Michael Kramer, no Clinton fan, awarded "Round 1" to Hillary, and said Rudy was the loser because he was "on one of his famous, petulant tears." Kramer cited the "Captain Jack" incident. "The mayor's rant," he said, "was petty and bullying." Kramer also slammed Giuliani for filling upstate talk-radio airwaves with "over-the-top" anti-Hillary commentary. Clinton continued to march through the snow.

By March 2, at least in a Siena College poll, the candidates were tied, 42 to 42. External events kept breaking Clinton's way. A jury acquitted the police of murder in the death of Amadou Diallo. George Bush became the all-but-certain Republican nominee for president. Both developments seemed to scare a few Democrats back into Hillary's column. Journalists began to describe Clinton as a greatly improved, dogged campaigner, and they noticed that she was closing in on 50 percent upstate. Democrat Chuck Schumer had hit that magic number when he knocked incumbent Republican Al D'Amato out of the Senate two years earlier. And then, with the race neck and neck, the mayor handed Clinton the lead. He did it not by attacking her or another politician, but by impugning the memory of a previously unknown resident of his city.

On March 16, an undercover cop working a "buy and bust" sting outside a Manhattan cocktail lounge tried to persuade a 26-year-old Haitian-American security guard named Patrick Dorismond to sell him some drugs. Dorismond took offense at the officers' overture. A scuffle erupted, a cop's gun went off, and Dorismond fell to the pavement dead. Amid the news of the fourth police shooting of an unarmed black man in the city in 13 months, Giuliani and his police commissioner, Howard Safir, released the dead man's sealed juvenile record to discredit him. The victim "wasn't an altar boy," the mayor said.

In fact, Dorismond had, literally, been an altar boy. He had even attended the same Catholic high school as Giuliani. As Time's Margaret Carlson would write, "Giuliani may want to consider saying he's sorry and letting Patrick Dorismond rest in peace." Instead, Giuliani said he had no regrets and had handled the matter "appropriately." Within days of the shooting and Giuliani's response, polls indicated that his electoral support within New York City, the advantage he'd enjoyed over any other potential GOP Senate candidate, had begun to collapse among two key groups, Latinos and Jews. At the start of the month, a Zogby poll had still shown Giuliani in the lead statewide; by March 25, another Zogby poll had Clinton 3 points ahead.

An early April New York Times poll gave Clinton an even larger lead, 8 points. Giuliani remained deadlocked with her upstate -- but then he scrapped an upstate campaign swing in order to attend the Yankees home opener, blowing off 400 ticket-holders to a "Women for Giuliani" luncheon in Rochester. Giuliani was unapologetic, telling reporters at the ballpark that he'd ignored the advice of his advisors so that he could do what he loved best. Clinton popped up outside a diner in Rochester, a portable microphone in her hand. "Well, I'm happy to be here," she said. "I have enjoyed coming to the Rochester area talking about the issues."

In a sense, it was all a replay of 1998 and early 1999, before either candidate had officially announced. Back then, Hillary had topped the polls because New Yorkers were, for a time, sympathetic to her and sick of Rudy. Throughout the state, voters had channeled their weariness with the GOP-dominated Congress' impeachment of President Clinton into support for his wife; at the same time, New York City voters expressed their irritation with Giuliani's insensitive handling of another police shooting -- the death of Amadou Diallo -- by withholding their support for him. Hillary as victim and Rudy as bully had meant a fleeting lead in the polls for the Democrat, one that evaporated once memories of Lewinsky and Diallo became less vivid. A year later, Rudy was again making Clinton the victim and himself the bully, and again helping his opponent.

After Dorismond, the bad news never stopped for Rudy. On April 27 he announced that he'd been diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer. Though he resumed campaigning within days of surgery, expressing eagerness to return to the trail, the New York Post soon published a photograph of the married father of two children standing next to a woman the tabloid described as a "Mystery Brunch Pal."

At the same time, the New York Conservative Party began to make good on its threat to back a third-party bid rather than endorse Giuliani. Former Rep. Joseph DioGuardi announced that he was seeking the nomination on the Conservative line, and party chair Mike Long called him "the right candidate." Just as in the present election cycle, when social conservatives have hinted they may boycott the candidacy of the pro-choice Giuliani, Long had been hinting throughout the 2000 Senate race that Giuliani would have to change his stand on abortion and several other litmus-test issues or forgo the Conservative Party's endorsement. No Republican had won statewide office in New York in more than two decades without appearing on the Conservative Party ballot line as well. In some cases, the endorsement had been worth 200,000 votes. Long's disenchantment was also personal; the endorsement had been withheld, at least in part, because of Giuliani's abrasive manner. "The mayor," said Long, "just doesn't know how to handle human beings."

Republican power broker Joseph Bruno, the majority leader of the state Senate, was soon pleading with Rudy to straighten out his marriage and focus on defeating Hillary. But by then it was too late. Giuliani was about to give himself the coup de grâce.

As Bruno's comments made headlines, the mayor disclosed at a May 10 press conference that he did indeed have a "very special friend." His secret affair with Judi Nathan had started some 10 months earlier, said Giuliani. By the way, he was also leaving his wife of 16 years, Donna Hanover.

Hanover apparently didn't know that last bit of information was coming. She learned about the dissolution of her marriage on the news. Badly stung, the mother of Giuliani's two children emerged from Gracie Mansion hours later to give her own press conference. Fighting back tears, Hanover accused her husband of conducting another earlier affair with a City Hall aide. He denied it.

After 10 rocky days of deliberation, Giuliani excused himself from the chaos. He dropped out of the race at a packed City Hall press conference on May 20. Giuliani cited his health. His once-promising career in politics looked finished, something he recognized in saying his illness taught him that politics was not the most important thing in his life any longer.

There were only 11 days left before the GOP's state nominating convention. Rep. Rick Lazio, who had never formally left the Senate race despite the party hierarchy's preference for Giuliani, stepped in to accept the Republican nomination.

As Giuliani had self-destructed, the media's conventional wisdom had congealed around the notion that while Clinton was a decent campaigner, she, like her husband, had also proved remarkably lucky in her enemies. When the obscure and inexperienced Lazio replaced Giuliani, however, a few Beltway pundits still tried to frame this as bad news for Hillary. The fact that Lazio was unknown outside Long Island became a threat to Hillary, as did the new GOP candidate's boyish demeanor. He was "baggage-free." "Rick Lazio," wrote one journalist, "could be [Clinton's] worst nightmare."

Lazio, unsurprisingly, began to campaign exactly as Giuliani had back when he was seen as the inevitable victor. Once again, the GOP's Senate candidate made Hillary the issue. Lazio picked up the Giuliani playbook, labeling Clinton a carpetbagger, a panderer, a flip-flopper. For a time, in summer, he made a race of it, but in the end aggression was counterproductive. The congressman's fate was sealed during the first Senate debate on Sept. 13, 2000. Mid-debate, Lazio strode across the stage to confront Clinton, repeatedly demanding that she sign a piece of paper pledging she would renounce the use of soft money in her campaign. The invasion of personal space made Lazio look desperate, adolescent and vaguely creepy. Twice in one race a Republican candidate's attacks on Hillary had provided no net benefit.

Lazio started the race 6 to 9 points behind and ended it 12 points behind. Clinton won comfortably in November, 55 to 43 percent, surviving the most expensive Senate contest in U.S. history. There had been only a narrow band of undecided voters available to her at the beginning of her run, but by Election Day she had brought nearly all of them into her camp.

In 2007, Giuliani is reprising his anti-Hillary routine. He has ripped her "socialist" healthcare plan, her $5,000 baby bonds and her criticism of Gen. David Petraeus' assessment of Iraq. He has revisited Wrigley Field to make fun of her Yankees leanings; he is saying that she has never run ... anything! And he has cast himself as the strongest antidote to Clinton in the Republican field, should she win the Democratic nomination. "He's almost itching to unleash against Hillary," someone associated with his presidential campaign told Salon.

It almost feels like 2000 all over again. Judging by 2000, however, another chorus of "Captain Jack" might not keep Hillary Clinton from her goal.

Shares