The moment Mitt Romney might look back on as an early sign of trouble, if his likely bid for the GOP nomination for president in 2012 winds up falling short, could be Liz Cheney's speech to the Southern Republican Leadership Conference Thursday night.

Usually, Cheney sticks to her bread-and-butter issue: the various ways the Obama administration is surrendering the nation to terrorists, leaving us all vulnerable to certain, and imminent, death. But for the SRLC crowd, Cheney found a new danger lurking. "Regardless of massive public disapproval of the healthcare plan, this president rammed it through on a partisan vote," she said, to roars of applause. "We still have time to stop this dangerous power play, what I think was one of the most arrogant power plays in American history." An aide said later Cheney thinks healthcare will do "significant damage to our nation," just like everything else she speaks on.

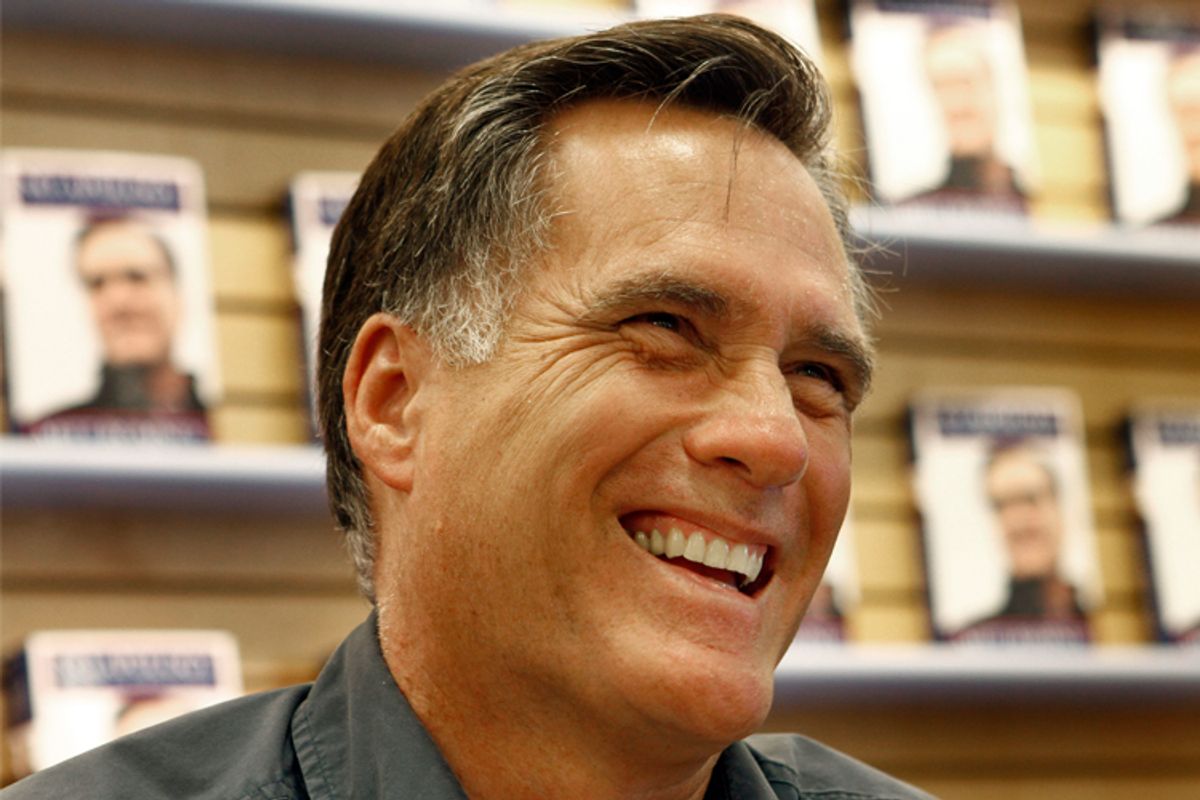

At the conference that typically serves as the unofficial kickoff to the next GOP presidential primary campaign, the new healthcare reform law was public enemy No. 1. Romney, of course, stayed away from the conference, continuing on a book tour that (strangely enough) includes quite a few stops in places like Iowa and New Hampshire. But back in New Orleans, speaker after speaker found bashing the healthcare law -- and promising to repeal it -- was the best way to win an ovation from the crowd of 3,000 activists.

Which could be a sign of danger for Romney. As governor of Massachusetts, he helped pass a plan that shares a lot of the features of the Obama reforms that everyone in New Orleans hated so much: an individual mandate to buy insurance, expanded Medicaid, subsidies to help people afford coverage. Perhaps to compensate, since the federal law passed, few Republicans have denounced it more lustily than Romney has; he's been calling for its repeal for weeks now, and his PAC's Rx for Repeal program is specifically funding GOP candidates for office who say they'll help undo it.

Romney's position is pretty clear -- he liked the Massachusetts law because it was limited to Massachusetts, but it shouldn't be expanded to the rest of the nation. "Whether you like what we did or think it stinks to high heaven, the point is we solved it at our level," he told a New Hampshire audience last week. "I like the things that are similar [to the Massachusetts plan], I don't like the things that are different, and that's why I vehemently oppose Obamacare." Romney points to the Massachusetts plan as an example of how he can fix problems, then pivots to opposing the federal law because -- he says -- it takes a "one size fits all" approach to all 50 states.

But will a nuanced position be firm enough to assuage the doubts of activists and donors who, for now at least, are more fired up about healthcare than they are about anything else the Obama administration is doing? "I think that's a stumbling block for him, and it certainly makes me hesitate about him," Ross Little, a member of the Republican National Committee from Louisiana, told me at the SRLC meeting. "That doesn't mean he won't be able to overcome it." I asked how Romney could do that, and nearly five seconds went by. "I'm not sure." Another Louisiana Republican, Jefferson Parish clerk Jon Gegenheimer, called the Massachusetts reform "this horrific healthcare plan which was sort of the basis for this Obamacare plan."

Of course, Romney still won the SRLC straw poll, getting more votes than any other potential candidate on the ballot from the crowd that stood and cheered at every mention of overturning the healthcare law -- even though he wasn't actually in New Orleans over the weekend. At the booth run by Evangelicals for Mitt, a grass-roots group of supporters that appears to be independent of Romney's operation, the topic apparently didn't even come up that much. "I came here expecting to talk a lot about healthcare with people," said David French, a conservative lawyer from Columbia, Tenn., who runs the group with his wife, Nancy. They were all over the conference, sponsoring parties and handing out Romney paraphernalia. "All the people we've interacted with, only two or three brought it up -- and the people who brought it up were Ron Paul supporters who wanted to discuss it from the libertarian point of view."

And just because many GOP activists are furious about healthcare now doesn't mean that will still be dominating the conversation over the next year or two, as the 2012 campaign actually unfolds. Or even if they are, that they'll decide their vote based on the issue. After all, after John McCain first ran for president, he sponsored campaign finance legislation (which carries his name) that conservatives considered an assault on the First Amendment, teamed up with Ted Kennedy to push immigration reform (twice), and joined most Senate Democrats to vote against George W. Bush's tax cuts. And then he went on to win the 2008 Republican nomination. There's more to a primary campaign than which candidate agrees the most with the base; otherwise, Dennis Kucinich might well have beaten out the Democratic field in 2008.

But while Romney seems to have settled on a way of talking about healthcare that explains the differences between his plan and Obama's, he might be better off, in the end, if he just stopped discussing it. One of the things that most alienated Romney from voters and his fellow GOP candidates in 2008 was his apparent willingness to attack rivals for positions he had once held himself. So far, this time around, he hasn't gone out of his way to emphasize the social issues that got him called a flip-flopper in 2008, preferring to play up his experience in business to address concerns about the economy. But the more he defends his position on healthcare reform, the more his potential opponents -- Democrats and Republicans -- might be tempted to bring back that charge from the last time out.

Shares