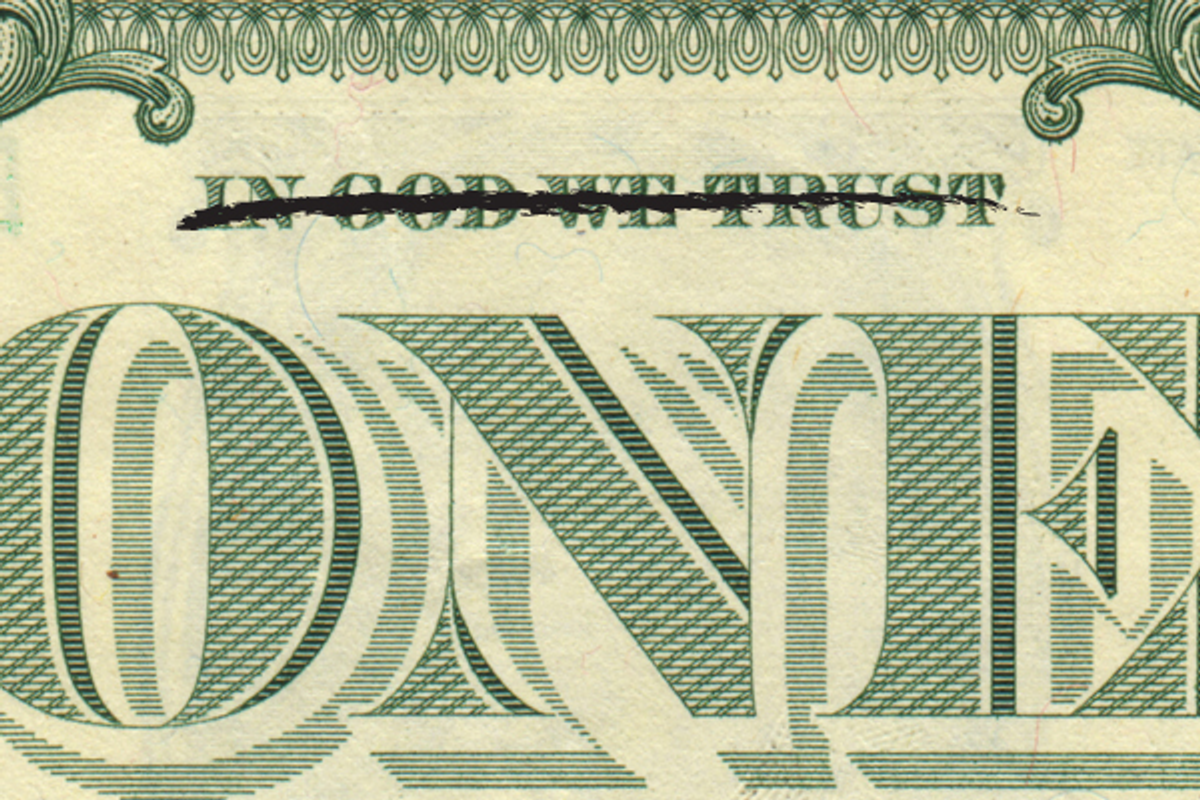

In between bragging about the number of people they've killed and vilifying gay soldiers, the GOP presidential candidates have spent the primaries demonstrating how little they respect the separation of church and state. Michele Bachmann seems to think God is personally invested in her political career. Both she and Rick Perry have ties to Christian Dominionism, a theocratic philosophy that publicly calls for Christian takeover of America's political and civil institutions. (Even Ron Paul, glorified by civil libertarians for his only two good policy stances -- opposition to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and drug prohibition -- sputtered about churches when asked during a debate where he'd send a gravely ill man without health insurance.)

GOP pandering to the religious right is just one of those facts of American public life, like climate change denial and creationism in schools, that leave secular Americans lamenting the decline of the country, and of reason and logic. Organized religion's grasp on the politics and culture of much of Europe has been waning for decades -- why can't we do that here?

GOP pandering to the religious right is just one of those facts of American public life, like climate change denial and creationism in schools, that leave secular Americans lamenting the decline of the country, and of reason and logic. Organized religion's grasp on the politics and culture of much of Europe has been waning for decades -- why can't we do that here?

But there are signs that American attitudes are changing in ways that may tame religion's power over political life in the future.

Annie Laurie Gaylor, founder of the Freedom from Religion Foundation, tells AlterNet that she thinks what happened in Europe is (slowly) happening here. While questioning religion remains controversial -- Gaylor says the group's work on church and state issues often elicits hate mail strongly suggesting they move to, you know, Europe -- atheism, skepticism and agnosticism are becoming more widely accepted.

"The statistics show there are more of us ... If you're in a room of people you can count on more to agree with non-belief or to be accepting of non-belief," says Gaylor.

Here are five trends that give hope one day religion will reside in the realm of personal choice and private worship, far away from politics -- something like what the Founders intended hundreds of years ago.

1. American religious belief is becoming more fractured

The intrusion of religion into places where it doesn't belong, like government or public education, naturally requires high levels of organization and control -- it's not something that just happens. So it's a good sign that even many Americans who maintain a personal religious faith are distancing themselves from heierarchical, top-down religion. Polls have repeatedly shown that even among the devout, emphatic proclamations of faith do not translate into actual churchgoing. In fact, church attendance rates hovered at around 40 percent until pollsters realized there's a major gap between what Americans tell them about their religious habits and their actual religious habits. Tom Flynn summarizes the over-inflation of U.S. churchgoing and offers more accurate stats:

Americans may believe in a god who sees everything, but they lie about how often they go to church. Since 1939, the Gallup organization has reported that 40 percent of adults attend church weekly. (The most recent figure is 42%.) Gallup's figure has long attracted skepticism. Were it true, some 73 million people would throng the nation's houses of worship each week. Even the conservative Washington Times found that "hard to imagine." New research suggests that there may be only half to two-thirds that many people in the pews.

Americans are also actively shaping their religious beliefs to fit their own values. Profiled in USA Today, religion statistics expert George Barna shares recent findings that show religion is becoming increasingly personal. Believers might drift from faith to faith until they find one that works for them, or cobble together a belief system drawn from many religious traditions. The U.S. is becoming a place of "310 million people with 310 million religions," Barna is quoted as saying.

2. Non-belief -- and acceptance of non-belief -- on the rise

Last month was the first time atheists were knocked from the top of America's most hated list, an honor that now belongs to the Tea Party. While this development may have more to do with the fact that the mainstream media's love affair with the Tea Party is not shared by most Americans, it also dovetails with increased visibility and acceptance of atheism.

Gaylor tells AlterNet that the FFRF's membership has never been bigger, and her observation conforms to larger trends. In a 2008 study by Connecticut's Trinity college, 15 percent of Americans polled as "nones," a group composed of vehement atheists, agnostics or people without religious affiliation. In 1990s, only 8.1 percent of the U.S. population could be categorized in this way, according to the report.

In an interview on NPR, Blair Scott, founder of the North Alabama Free Thought Association, says he's noticed people are becoming more and more open-minded about non-belief: "I mean, I've been the victim of discrimination and harassment. They are very real, and they are legitimate concerns that people have. But what we've seen recently is an increase in the general public's, maybe not acceptance, but more curiosity of what atheism is and is not."

Scott also points out that the controversial writing of the New Atheists like Richard Dawkins regularly makes it onto the New York Times bestseller list, which in turn helps popularize atheist arguments and philosophies, even in unexpected places:

I mean, I expect an atheist group in New York, L.A., San Francisco, Seattle, etc. But where we're seeing them pop up is little places like Jackson, Mississippi; Hattiesburg, Mississippi; Tallahassee, Florida, you know, so these little bitty mid-size and small towns, and that's an incredible phenomenon because what that means is that these people are finally willing to say, okay, I live in a small town or a midsize city, but you know what, I know there's others out there like me.

3. Growing numbers of young people who do not identify as religious

America is still a shockingly religious country by Western standards. But a more nuanced breakdown of religious belief tells a different story. Statistically the most devout demographics are middle-aged and older, while young Americans are increasingly likely to shun religious identification, according to professors Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, writing in the L.A. Times:

As recently as 1990, all but 7 percent of Americans claimed a religious affiliation, a figure that had held constant for decades. Today, 17 percent of Americans say they have no religion, and these new "nones" are very heavily concentrated among Americans who have come of age since 1990. Between 25 percent and 30 percent of twentysomethings today say they have no religious affiliation — roughly four times higher than in any previous generation.

The writers point to a surprising culprit: the powerful religious right movement whose tight grip on American political life has steered the country in an aggressively right-wing direction for decades:

Throughout the 1990s and into the new century, the increasingly prominent association between religion and conservative politics provoked a backlash among moderates and progressives, many of whom had previously considered themselves religious. The fraction of Americans who agreed "strongly" that religious leaders should not try to influence government decisions nearly doubled from 22 percent in 1991 to 38 percent in 2008, and the fraction who insisted that religious leaders should not try to influence how people vote rose to 45 percent from 30%.

This backlash was especially forceful among youth coming of age in the 1990s and just forming their views about religion. Some of that generation, to be sure, held deeply conservative moral and political views, and they felt very comfortable in the ranks of increasingly conservative churchgoers. But a majority of the Millennial generation was liberal on most social issues, and above all, on homosexuality. The fraction of twentysomethings who said that homosexual relations were "always" or "almost always" wrong plummeted from about 75 percent in 1990 to about 40 percent in 2008. (Ironically, in polling, Millennials are actually more uneasy about abortion than their parents.)

4. Hate group that exploited religion to bash gays hemorrhaging funds

As Americans increasingly reject the politics of hate, the right-wing groups that thrive on it are facing tough times.

While many practicing Christians live their faith without trying to impose their values on others, the aggressive Christian extremism of organizations like Focus on the Family has always been charged by the demonization of people who are not like them.

Unfortunately for FOTF, many Americans just don't hate gay people enough to keep them afloat. In 2008, FOTF had to cut its staff by 18 percent. Last week, FOTF had to do another round of cuts, again citing a drop in donations (though it claims the lower funding is a result of tough economic times). On the issue of gay rights, Focus on the Family CEO Jim Daly said:

"We're losing on that one, especially among the 20- and 30-somethings: 65 to 70 percent of them favor same-sex marriage," Daly said in the interview. "I don't know if that's going to change with a little more age—demographers would say probably not. We've probably lost that."

It's important to note that the religious right is still exceptionally powerful, as evidenced by the prominent role right-wing Christianity still plays in American politics. It is a powerful movement with lots of followers, smart P.R. and tons of organizational muscle. But as Sarah Seltzer pointed out, "The Christian right is far from dead, but it's good to see one of its biggest wedge issues losing its power to wedge."

5. Getting married by friends

On a lighter note, it looks like increasing numbers of Americans are looking to jettison religion out of their marriages as well. The Washington Post reported last week that more Americans are choosing wedding ceremonies without the trappings of religion, including the clergy. Reporter Michele Boorstein finds a crew of college friends who officiate at each other's weddings:

Their decision to forgo the more traditional route is a slightly extreme example of a once-quirky trend that is becoming more mainstream. A study last year by TheKnot.com and WeddingChannel.com showed that 31 percent of their users who married in 2010 used a family member or friend as the officiant, up from 29 percent in 2009, the first year of the survey.

Boorstein points out this trend is likely the result of young people's drift away from traditional expressions of religious faith.

Shares