In the light of President Bush's attempt at Fort Bragg, N.C., last Tuesday to co-opt the July Fourth celebrations to support his war, it is time for some counter-revisionist history.

The American Revolution was not about tea. It was about rum: the real spirit of 1776.

The tea that was thrown into Boston Harbor was actually tax free, and the men throwing it overboard were doing so at the behest of local merchants who had warehouses filled with more expensive smuggled tea that they could sell only if the British East India Co.'s cheaper cargo was unloaded. They knew that no amount of patriotism would stop the Bostonians from buying a cheaper product.

But the real conflict between the colonists and Britain began over taxes on molasses, not tea. And that's where the French come in. The Founding Fathers not only loved the French, but they also loved the molasses that Paris' Caribbean colonies produced -- and they loved even more the rum that New England distillers made from it.

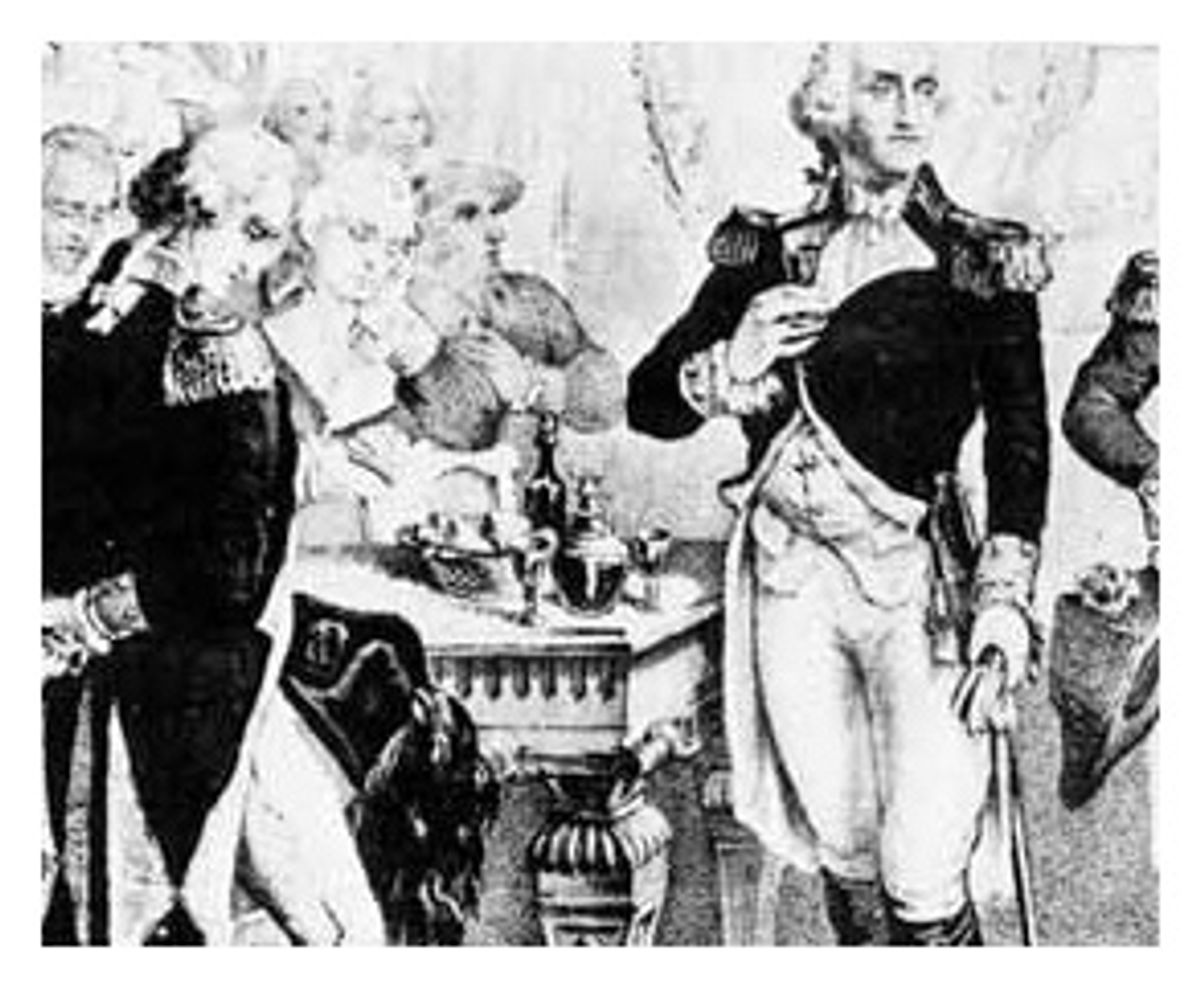

Years of temperance pressure and Prohibition -- and probably the Walt Disney Co. and Hollywood -- have essentially shoved the real history of the Revolution down a memory hole, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the iconic Currier & Yves print of Washington's farewell to his officers.

The 1848 version, above, has the first president hoisting a glass to toast his comrades in arms, with a carafe on the table behind ready for refills. In the 1867 version, below, after 20 years of relentless temperance agitation, the carafe has morphed into a cocked hat, and the president's glass has disappeared, leaving Washington clutching his lapel in a strange Napoleonic gesture.

New England had an insatiable thirst for molasses, since a gallon of it made a gallon of rum, and the inhospitable lands of the Northeast did not produce enough grain to make whiskey. The colonists drank a lot of the New England rum they produced and sold the rest to the Indians, with devastating social results, or bartered the rum for slaves from West Africa, with equally devastating results there. Benjamin Franklin chillingly put it that "indeed if it be the design of Providence to extirpate these Savages in order to make room for cultivators of the earth, it seems not improbable that Rum may be the appointed means. It has already annihilated all the tribes who formerly inhabited the Sea-Coast."

However, they could not get molasses from the British colonies in the Caribbean, who used it to make their own -- and much better -- rum. Franklin actually wrote poetry about punch made with Jamaica rum!

So the colonists got their molasses from the French islands. Paris would not let its colonies produce rum for export lest it compete with French wine and brandy, so the French had a lake of molasses left over from sugar refining.

The ticklish problem was that for much of the 18th century the French and the British were locked in a life-or-death struggle -- and no more so than in North America, where the French and their Indian allies posed a constant threat to the British settlers.

However, business is business, and the colonists did not let little details like wars interfere with commerce. They traded with the French enemy throughout the wars being fought for the survival of the American colonies. At one point the British Royal Navy ships based in Jamaica were unable to go to sea because they did not have enough flour to provision themselves, while as British Adm. Augustus Keppel pointed out, the French ships and garrison in Hispaniola had no such difficulties because of "the large supplies they have lately received from their good friends the New England flag of truce vessels," which sailed there under the guise of returning prisoners.

When New York merchants heard that Britain was about to go to war against France's ally, Spain, their response was to try to get permission from the governor to sell supplies to the Spanish garrison in Florida quickly, before the official declaration arrived. The end of what is known here as the French and Indian War shaped the modern world. The British chased the French out of North America completely -- but they ended up paying a quarter of their GDP in taxes to pay off the deficit that had secured the victory. They thought the colonists should help, and they knew that local officials could be bribed and bullied. So they gave the Navy the job of collecting customs duties on the molasses -- and the Navy was not gentle with the colonial merchants who had been trading with the French enemy so recently.

Freed from the French threat, the colonists increasingly regarded the British connection as a burden rather than a protection and ended up welcoming the French fleet and armies to get rid of the British. Even during the war, rum was the lifeblood of the opposing forces. In 1775 Abigail Adams wrote indignantly to her husband that British Gen. Thomas Gage in Boston had "ordered all the molasses to be distilled into rum for the soldiers: taken away all licenses, and given out others, obliging to a forfeiture of ten pounds if any rum is sold without written orders from the General." Equally concerned with a rum gap, Washington wrote to Congress in 1777 suggesting "erecting Public Distilleries in different States." He went on to explain, "The benefits arising from the moderate use of strong Liquor have been experienced in all Armies and are not to be disputed." Indeed, he anticipated modern patriots when in 1781 he complained to Gen. William Heath because the latter was providing French wine to Continental soldiers, when everybody knew that they preferred rum. Washington laid down firmly, "Wine cannot be distributed the Soldiers instead of Rum, except the quantity is much increased. I very much doubt whether a Gill of rum would not be preferred to a pint of small wine."

New Hampshire rose to the call and levied each town to provide 10,000 gallons of West India rum for the Revolutionary Army. It is ironic that Gen. Washington thought so highly of the martial virtues of rum, since one of his few outright military victories in the field -- over the 1,300 Hessians at Trenton, N.J., on Christmas Day 1776 -- was reputedly because the enemy was overfortified with the Christmas spirit.

Of course this is all ancient history. But President George Washington made and drank rum in prodigious quantities, and President George W. Bush, like the Taliban, is a total abstainer. Which one would you prefer to lead your country?

Shares