We're in the middle of a national debate about regulation: how it works, who benefits, whether to do it, and so on. I know I risk sounding like David Brooks talking like this, but it's true: healthcare, financial reform, energy emissions -- everywhere you look, the private sector is failing us and liberal technocrats in Washington are trying to prod it ever-so-gently back onto course.

It's not the main regulation story in the news today -- that, obviously, is the ongoing fight over how to rein in risk-happy banks -- but the New York Times has a long investigative piece about coal mine safety violations that's more revealing, in a way, than any reporting about Mitch McConnell and Chris Dodd arguing over bank liquidation authority.

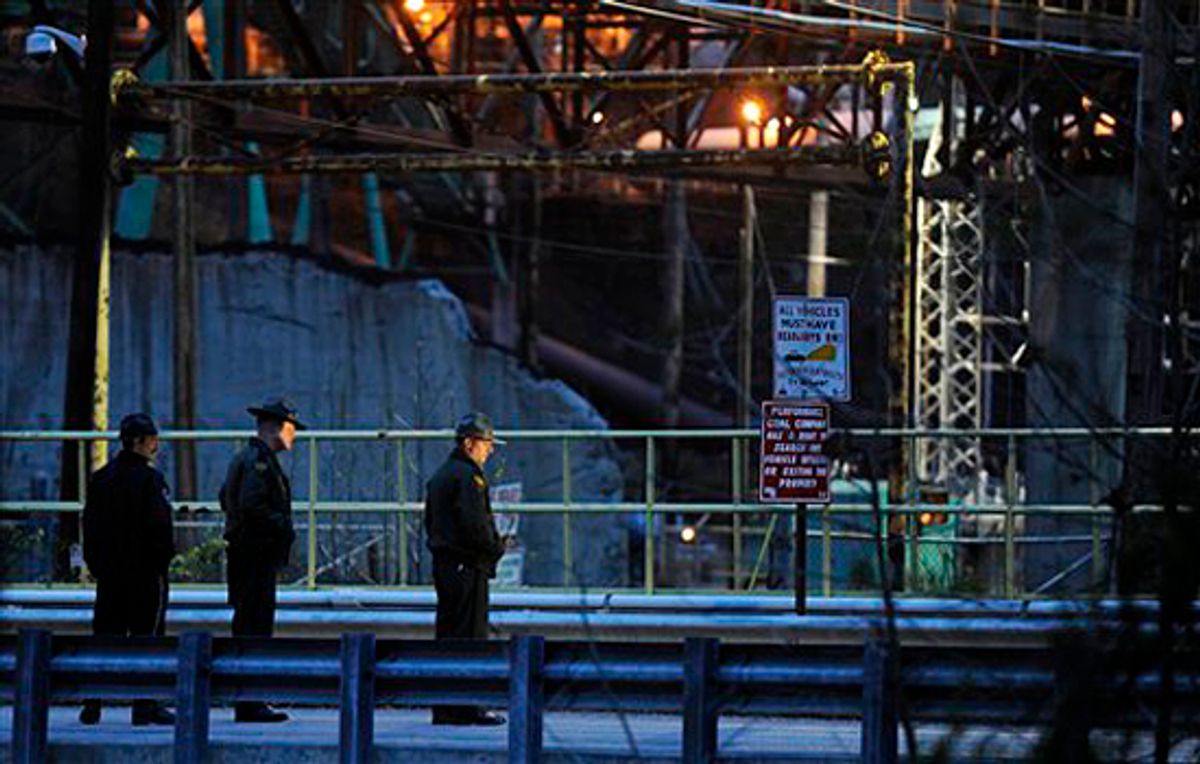

The article, titled "2 mines show how safety practices vary widely in U.S.," demonstrates how enormous the distance can become between rules and practices. If a company like Massey Energy -- owner of the recently collapsed coal mine at Upper Big Branch -- wants to break the rules, it currently has practically unlimited power to do so.

At Upper Big Branch, miners were aware all year of a methane gas buildup. They'd blocked off its source, an unused shaft, with garbage and rags, but, said an anonymous foreman, "Every single day, the [methane] levels were double or triple what they were supposed to be." Why does this foreman remain nameless? "The foreman, who is now working with federal prosecutors and elected officials investigating the mine, asked not to be identified because speaking out is not acceptable in the culture of his company, Massey Energy."

A Massey spokeswoman told the Times, "It’s important to note, however, that all [Mine Safety and Health Administration] violations must be abated. Most citations are corrected the same day, often immediately. For those that require more time, a deadline is given by M.S.H.A. to correct the situation." Yet the backlist of complaints reveals a company that seemed happy to flout the rules and able, predictably, to get away with it.

Now, in the wake of a catastrophe that has all of West Virginia in mourning, the trail of federal violations issued to Upper Big Branch, many of them in the weeks leading up to the explosion, seems infused with foreboding.

"The methane and dust control plan is not being followed."

"The lifeline in the primary escape way" is not being maintained.

"In case of an emergency the men on this section would not have fresh air in the primary escapeway."

“Management engaged in aggravated conduct constituting more than ordinary negligence, in that production was deemed more important than conducting parameter checks.”

Industrial work like mining produces a certain kind of deep, hands-on knowledge. There isn't much in the way of the division of labor you usually find in a factory or an office. In a coal mine, everybody pretty much knows what's going on. And at Massey, everybody seems to have known both that they were in some danger, and that they were not supposed to talk about it. Said a foreman, "I have had guys come to me and cry. Grown men cried -- because they are scared." An electrician recognized the danger, but couldn’t do anything about it. "If you worked for them, you didn’t ask questions about whether some step like running a cable around the breaker was a smart idea. You just did it."

The examples of this enforced silence at Massey go on and on. A set of doors interfered with airflow, and miners wanted to cut a shaft around them for air. The company said no. In fact, Massey would actually manipulate safety conditions to appear better than they were for inspections; guards told miners when an inspector was coming, with the expectation that they would move around equipment to produce inaccurately positive measurements.

The article -- which is absolutely worth reading in full -- is mainly a portrait of Massey's negligence. But to make the point that mining, while dirty and dangerous, doesn’t have to be careless, the authors throw in a comparison. TECO, another Appalachian coal mining company, has a record of going above the requirements of the law, and firing foremen who fail to keep up standards. Massey's safety record is abysmal; TECO's, while not flawless, is very good. This isn't rocket science.

Reading about Massey and TECO right now, it's hard not to think of Goldman Sachs. The letter of the law is important, but the culture of a company matters, and if management is interested in taking enormous risks in the name of keeping up production, our understaffed, undertoothed regulatory apparatus often just can't do much to interfere. Usually, it's the workers themselves -- whether they're coal miners or derivatives traders -- who know best the risks of what they're doing. But if there's a structure in place to keep them doing it, whether it's the promise of huge bonuses or the threat of company intimidation, then management is going to get its way.

The difference, of course, is that mining companies endanger their workers when they force them to keep quiet. Banks, on the other hand, enrich their staff by taking on too much risk, and endanger everyone else. But from the standpoint of the public interest, both are entirely unacceptable outcomes. It's not the kind of thing that a president is allowed to say anymore, but sometimes, the management of some misbehaving company is not just a friend gone astray. Sometimes, the federal government has to bring its full weight down to break the power of Goldman's Lloyd Blankfein, or Massey's Don Blankenship. This isn't just why we have regulators. At some basic level, it's why we have a federal government. Too bad we never get to use the thing.

Shares