Barack Obama's decision to deliver a speech this Thursday on the "events in the Middle East and North Africa and U.S. policy in the region" is baffling as much for its timing and venue as for its purpose.

The speech, planned for a while, is now the day before Obama meets Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with whom relations have been cool since the two squared off over Israel’s illegal settlement enterprise in the occupied Palestinian territories, and the president blinked first.

Perhaps the decision on timing was made to preempt Netanyahu’s effort to set the terms of the debate. The Israeli leader clearly aims to flood the nation with Israel’s message when he addresses a joint meeting of Congress on May 24 as well as the annual conference of AIPAC. This, according to members of Netanyahu’s Likud party quoted in Haaretz, is: No to an Israeli return to the 1967 lines; no to a compromise on Jerusalem; no to more construction freezes of the settlements. Instead, look for excoriation of the Fatah-Hamas unity deal. And expect no mention of how the ballooning of Israeli settler numbers to over half a million today dealt a body blow to peace.

The timing of the news of George Mitchell's resignation as Obama's Middle East envoy is also puzzling. Mitchell actually left in early April, but the announcement was only made Friday, and the resignation takes effect the day Obama is due to meet Netanyahu.

What stark, surely unintentional, symbolism of the failure of U.S. policy toward the Arab-Israeli conflict since the first Bush administration. That policy has been based on two faulty foundations: That a people living under occupation can negotiate the terms of freedom with an occupying military force that controls everything from movement (including that of the Palestinian negotiators themselves), to tax revenues, to the population registry; and that the U.S. can still insist on being the lead mediator even as it sustains Israel’s occupation through military aid and diplomatic cover.

The steep trajectory of failure is spotlighted by the choice of venue for the president’s speech. What a contrast Obama's visit to the State Department on Thursday will be to the second day of his presidency, when he used that same backdrop to appoint Mitchell as his envoy amidst soaring global hopes of a different approach.

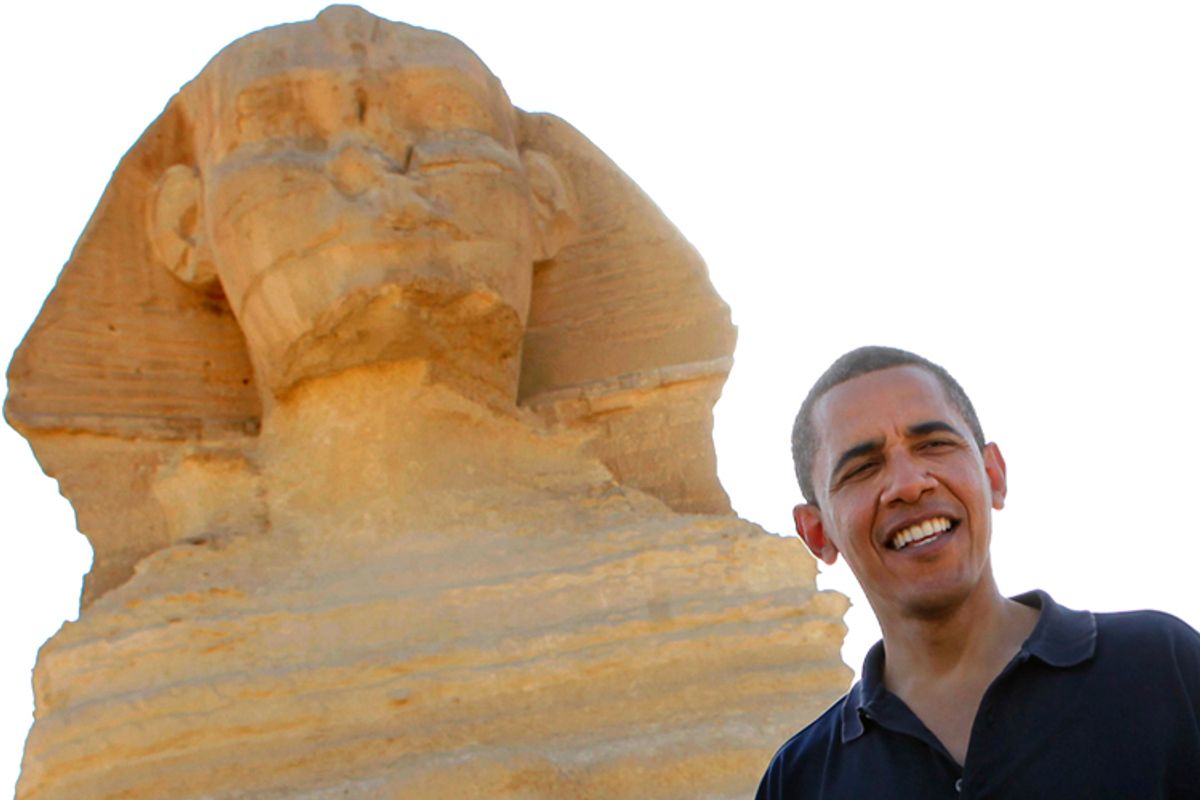

And what a far cry the State Department setting is from the "timeless city of Cairo," as Obama described it in the opening of his warmly welcomed first speech to the Arab and Muslim worlds in June 2009. Those great expectations were soon deflated. A poll conducted in six Arab countries last summer showed that only 16% of respondents felt positive about U.S. policy, as compared to 51% at the start of his administration. Perhaps the return to the State Department is an attempt to signal a more modest agenda, and acknowledge the limits of his presidential powers.

Finally, what is the purpose of the speech? There is no shortage of issues to address, including the U.S. position on the contours of a final Middle East settlement, the killing of Osama Bin Laden, and the Arab Spring. But it is hard to see what Obama could say to make a difference to the region's perceptions of U.S. policy -- if the speech is indeed intended for foreign rather than domestic consumption.

The Arab Spring? Viewed from the Arab street, the administration supported the Tunisian and Egyptian regimes and only switched when the people’s determination to stay the course became clear. The West is seen to serve its own agenda, as illustrated by the conflicting responses to Libya, where it is taking military action against the dictatorship, and Bahrain, where the U.S. Fifth Fleet is headquartered and where the regime has had a free hand against citizens demanding rights and dignity. And there are other gaps between what the U.S. says and what it does: reluctance to fully withdraw from Iraq, including "trainers," contractors, and bases; ramping up the war in Afghanistan; and backtracking on closing Guantanamo.

The killing of Bin Laden? Had this taken place in the heat of war soon after the attacks of September 11, the region’s sympathies would have been with the U.S. Now, the prevailing view is summed up by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood leader interviewed in The Washington Post: "For us, Osama bin Laden never represented Islam… Even though it was war, it didn’t give America the right to kill a person while the forces could capture him."

A U.S. vision of Middle East peace? Administration officials have continued to insist -- despite all the evidence to the contrary -- that only direct talks will bring peace. They have opposed the Palestinian leadership's plan to seek full membership of the United Nations, even though they have left it no other recourse.

Obama faces a yawning credibility gap on Middle East peace. If he was unwilling to pressure Israel to even freeze settlements, few will believe he can swing an actual withdrawal of Israeli soldiers and settlers at a time when he is actively seeking re-election. And people will continue to hold America responsible for Israel’s actions, knowing full well Israel could not sustain its occupation were it not for U.S. military aid and diplomatic cover.

What, then, are Obama’s options? Since he has decided to speak, he could consider three things. Avoiding any hint of arrogance by recognizing America's minimal role in supporting the Arab uprisings and its major role in sustaining dictatorship. Announcing a credible timeline of concrete measures for the withdrawal of U.S. troops, trainers, contractors, and bases from Iraq, Afghanistan, and the rest of the region. And providing evidence of a willingness and ability to deliver on Middle East peace and stop subsidizing Israel’s occupation.

Anything else will be greeted with disdain by peoples now determined to take their destiny into their own hands.

Nadia Hijab is Co-Director of Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network, and a writer, public speaker and media commentator. She authored "Womanpower: The Arab Debate on Women at Work" (Cambridge University Press) and co-authored "Citizens Apart: A Portrait of Palestinians in Israel" (I. B. Tauris).

Shares