Having denounced liberals as crypto-communists for half a century during the Cold War, the American right now routinely accuses the center-left of being fascist. This libel was given currency in Jonah Goldberg's 2009 book "Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, From Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning." From the support of a few progressives a century ago for eugenics, and expressions of admiration by a few 1920s liberals for Mussolini’s ability to make the trains run on time, Goldberg and others on the right have crafted the latest in a series of right-wing conspiracy theories about American history, this one claiming that Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt deliberately set the U.S. on the road to an American version of Mussolini’s corporate state.

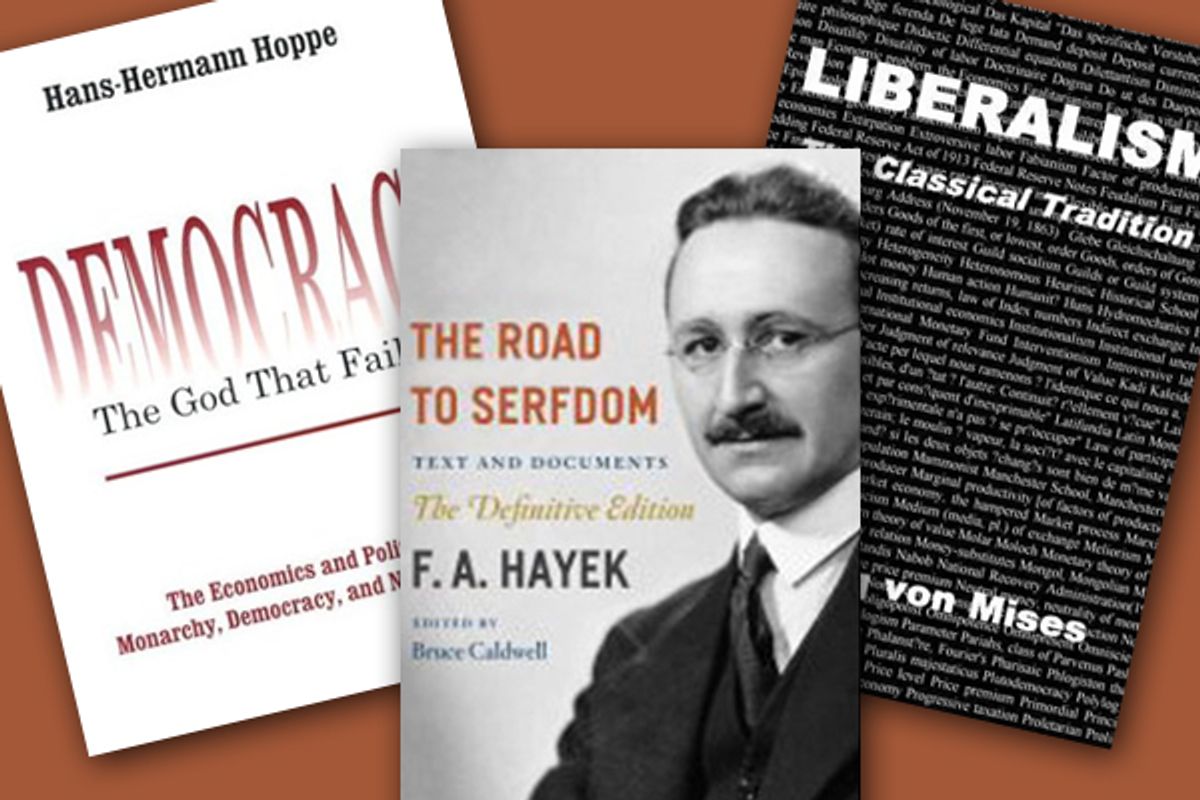

Given their professed interest in admirers of Mussolini, it is curious that American conservatives and libertarians have not seen fit to discuss the view of fascism held by one of the heroes of modern American libertarianism, the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises. In his book "Liberalism," published in 1927 after Mussolini had seized power in Italy, Mises wrote:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aimed at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has for the moment saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.

Friedrich von Hayek, who was, along with von Mises, one of the patron saints of modern libertarianism, was as infatuated with the Chilean dictator Gen. Augusto Pinochet as von Mises was with Mussolini, according to Greg Grandin:

Friedrich von Hayek, the Austrian émigré and University of Chicago professor whose 1944 Road to Serfdom dared to suggest that state planning would produce not "freedom and prosperity" but "bondage and misery," visited Pinochet’s Chile a number of times. He was so impressed that he held a meeting of his famed Société Mont Pélérin there. He even recommended Chile to Thatcher as a model to complete her free-market revolution. The Prime Minister, at the nadir of Chile’s 1982 financial collapse, agreed that Chile represented a "remarkable success" but believed that Britain’s "democratic institutions and the need for a high degree of consent" make "some of the measures" taken by Pinochet "quite unacceptable."

Like Friedman, Hayek glimpsed in Pinochet the avatar of true freedom, who would rule as a dictator only for a "transitional period," only as long as needed to reverse decades of state regulation. "My personal preference," he told a Chilean interviewer, "leans toward a liberal [i.e. libertarian] dictatorship rather than toward a democratic government devoid of liberalism." In a letter to the London Times he defended the junta, reporting that he had "not been able to find a single person even in much maligned Chile who did not agree that personal freedom was much greater under Pinochet than it had been under Allende." Of course, the thousands executed and tens of thousands tortured by Pinochet’s regime weren’t talking.

The Pinochet dictatorship was admired by the right in the U.S. and Britain for turning Chile’s economic policy over to disciples of Milton Friedman and the University of Chicago, who inflicted disastrous social experiments like the privatization of social security on Chile’s repressed population. Following the libertarian reforms, the Chilean economy collapsed in 1982, forcing the nationalization of the banking system and government intervention in industry. According to Grandin:

While he was in Chile Friedman gave a speech titled "The Fragility of Freedom" where he described the "role in the destruction of a free society that was played by the emergence of the welfare state." Chile’s present difficulties, he argued, "were due almost entirely to the forty-year trend toward collectivism, socialism and the welfare state . . . a course that would lead to coercion rather than freedom."

Friedman politely neglected to mention the lack of political and civil liberty under the Pinochet regime. Many of its victims were drugged and taken in military airplanes to be dropped over the South Atlantic, with their bellies slit open while they were still alive so that their bodies would not float and be discovered.

One of the members of Pinochet’s cabinet, Jose Piñera, has enjoyed a second career at the leading American libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute, and is credited with having influenced George W. Bush’s failed attempt to partly privatize Social Security in America. The Cato website says:

Distinguished senior fellow José Piñera is co-chairman of Cato's Project on Social Security Choice and Founder and President of the International Center for Pension Reform. Formerly Chile's Secretary of Labor and Social Security, he was the architect of the country's successful reform of its pension system. As Secretary of Labor, Piñera also designed the labor laws that introduced flexibility to the Chilean labor market and, as Secretary of Mining, he was responsible for the constitutional law that established private property rights in Chilean mines.

Piñera, the brother of Chile’s billionaire president Sebastian Piñera, has a personal website in which he claims that he played a major role in the transition to democracy in Chile. Piñera’s portrayal of himself as a champion of democracy is somewhat undercut on the same Web page by several defenses of Pinochet's regime that he includes, including this one by a writer in an Australian magazine:

Indeed, in all 17 years of military rule, the total number of dead and missing -- according to the official Retting Commission -- was 2,279. Were there abuses? Were there real victims? Without the slightest doubt. A war on terror tends to be a dirty war.

Still, in the case of Chile, and contrary to news reports, the number of actual victims was small.

The Cato Institute’s problem with democracy is not limited to its appointment of a former functionary of a mass murderer to direct its retirement policy program. Cato Unbound recently hosted a debate over whether libertarianism is compatible with democracy. Milton Friedman’s grandson Patri concluded that it is not:

Democracy Is Not The Answer

Democracy is the current industry standard political system, but unfortunately it is ill-suited for a libertarian state. It has substantial systemic flaws, which are well-covered elsewhere,[2] and it poses major problems specifically for libertarians:

1) Most people are not by nature libertarians. David Nolan reports that surveys show at most 16% of people have libertarian beliefs. Nolan, the man who founded the Libertarian Party back in 1971, now calls for libertarians to give up on the strategy of electing candidates! …

2) Democracy is rigged against libertarians. Candidates bid for electoral victory partly by selling future political favors to raise funds and votes for their campaigns. Libertarians (and other honest candidates) who will not abuse their office can't sell favors, thus have fewer resources to campaign with, and so have a huge intrinsic disadvantage in an election.

In his recommendations for further reading, Friedman included the Austrian economist Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s book "Democracy: The God That Failed," which appeared in 2001, following the fall of the Berlin Wall, during the greatest wave of global democratization in history. In his Cato Unbound manifesto, Friedman called on his fellow libertarians to give up on the whole idea of the democratic nation-state and join his movement in favor of "seasteading," or the creation of new, microscopic sovereign states on repurposed oil derricks, where people who think that "Atlas Shrugged" is really cool can be in the majority for a change.

In a similar spirit, a libertarian economics blogger named Arnold Kling has proposed his own alternative to democracy, which he calls "competitive government":

In this essay, I will suggest that competitive government might be better than democratic government at satisfying the desires of the governed. In democratic government, people take jurisdictions as given, and they elect leaders. In competitive government, people take leaders as given, and they select jurisdictions.

When it comes to American history, libertarians tend retrospectively to side with the Confederacy against the Union. Yes, yes, the South had slavery -- but it also had low tariffs, while Abraham Lincoln's free labor North was protectionist. Surely the tariff was a greater evil than slavery.

The posthumous induction of Jefferson Davis into the libertarian hall of fame was too much for David Boaz, a vice president of Cato. In a 2010 essay in Reason magazine titled "Up From Slavery: There’s No Such Thing as a Golden Age of Lost Liberty," Boaz observed that even whites in the antebellum North "did not actually live in a free society ... Liberalism seeks not just to liberate this or that person, but to create a rule of law exemplifying equal freedom. By that standard, even the plantation owners did not live in a free society, nor even did people in the free states."

Boaz asked his fellow libertarians, "If you had to choose, would you rather live in a country with a department of labor and even an income tax or a Dred Scott decision and a Fugitive Slave Act?" It says something that in 2009 this question stirred up a controversy on the libertarian right.

Libertarians and conservatives, to be sure, can point to many examples of naive liberals in the last century who embarrassed themselves by praising this or that squalid, tyrannical communist regime, from the Soviet Union and communist China to petty police states like North Korea, communist Vietnam and Castro’s Cuba. But the apologists for tyranny on the left were always opposed by anti-communist liberals and anti-communist democratic socialists. Where were the anti-authoritarian libertarians, denouncing libertarian fellow travelers of Pinochet like von Hayek and Milton Friedman?

For that matter, where was the libertarian right during the great struggles for individual liberty in America in the last half-century? The libertarian movement has been conspicuously absent from the campaigns for civil rights for nonwhites, women, gays and lesbians. Most, if not all, libertarians support sexual and reproductive freedom (though Rand Paul has expressed doubts about federal civil rights legislation). But civil libertarian activists are found overwhelmingly on the left. Their right-wing brethren have been concerned with issues more important than civil rights, voting rights, abuses by police and the military, and the subordination of politics to religion -- issues like the campaign to expand human freedom by turning highways over to toll-extracting private corporations and the crusade to funnel money from Social Security to Wall Street brokerage firms.

While progressives betray their principles when they apologize for autocracy, libertarians do not. Today’s libertarians claim to be the heirs of the classical liberals of the 19th century. Without exception the great thinkers of classical liberalism, like Benjamin Constant, Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill, viewed universal suffrage democracy as a threat to property rights and capitalism. Mill favored educational qualifications for voters, like the "literacy tests" used to disfranchise most blacks and many whites in the South before the 1960s. After the Civil War, Lord Acton wrote to Robert E. Lee, commiserating with him on the defeat of the Confederacy.

In a letter to an American in 1857, Macaulay wrote:

Dear Sir: You are surprised to learn that I have not a high opinion of Mr. JEFFERSON, and I am surprised at your surprise. I am certain that I never wrote a line, and that I never, in Parliament, in conversation, or even on the hustings -- a place where it is the fashion to court the populace -- uttered a word indicating an opinion that the supreme authority in a State ought to be intrusted to the majority of citizens told by the head; in other words, to the poorest and most ignorant part of society. I have long been convinced that institutions purely democratic must, sooner or later, destroy liberty, or civilization, or both.

By "purely democratic" Macaulay meant universal suffrage; he opposed democracy even with checks and balances and written constitutions.

It is quite plain that your Government will never be able to restrain a distressed and discontented majority. For with you the majority is the Government, and has the rich, who are always a minority, absolutely at its mercy. The day will come when, in the State of New-York, a multitude of people, none of whom has had more than half a breakfast, or expects to have more than half a dinner, will choose a Legislature. Is it possible to doubt what sort of Legislature will be chosen? On one side is a statesman preaching patience, respect for vested rights, strict observance of public faith. On the other is a demagogue ranting about the tyranny of capitalists and usurers, and asking why anybody should be permitted to drink champagne and to ride in a carriage, while thousands of honest folks are in want of necessaries. Which of the two candidates is likely to be preferred by a working man who hears his children cry for more bread?

Macaulay’s solution was to limit voting rights to those who drink champagne and ride in carriages, on the proto-Reaganite theory that some of their wealth would trickle down to people with hungry, crying children, "none of whom has had more than half a breakfast, or expects to have more than half a dinner."

The history of democratic nation-states since the 19th century proves that Macaulay, and von Mises, and Hayek, as well as lesser lights like Patri Friedman, have been right to argue that democracy is incompatible with libertarianism. Every modern, advanced democracy, including the United States, devotes between a third and half of its GDP to government, in both direct spending on public services like defense and transfer payments. Given the power to vote, most populations will not only vote for some system of government-backed social insurance, but also for all sorts of interventions in individual behavior that libertarians object to, from laws banning nudity in public to laws mandating that people support their children, do not torture or neglect their pets and water their lawns during droughts according to scheduled rationing.

Unfortunately for libertarians who, like Hayek, prefer libertarian dictatorships to welfare-state democracies, even modern authoritarians reject the small-government creed. The most successful authoritarian capitalist regimes, such as today’s China and South Korea and Taiwan before their recent transitions to democracy, have been highly interventionist in economics, promoting economic growth by means of state-controlled banking, state-owned enterprises, government promotion of cartels, suppression of wages and consumption, tariffs and nontariff barriers to imports, toleration of intellectual piracy, massive infrastructure projects to help industry, and subsidies to manufacturers in the form of artificially cheap raw materials, energy and land.

The dread of democracy by libertarians and classical liberals is justified. Libertarianism really is incompatible with democracy. Most libertarians have made it clear which of the two they prefer. The only question that remains to be settled is why anyone should pay attention to libertarians.

Shares