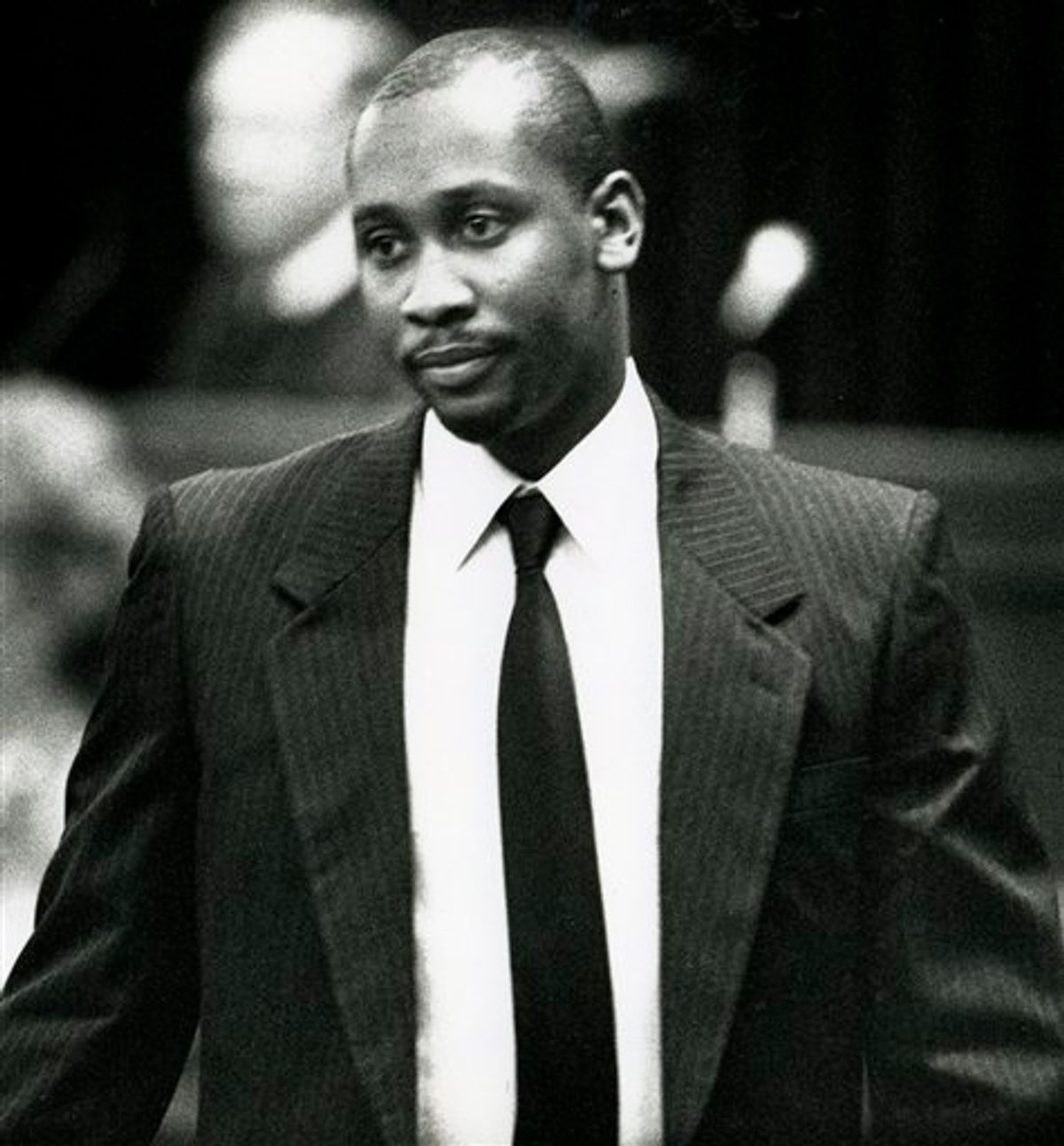

Unless there's some unforeseen intervention, 42-year-old Troy Davis will be injected with poison and killed by the state of Georgia at 7:00 tonight -- even though nearly every witness who testified at his murder trial has since recanted, even though there is no physical evidence linking him to the killing, even though there is strong evidence that the police mishandled the case, and even though another witness who testified against Davis may have confessed to the crime just two years ago.

Davis, a black man convicted in 1991 of killing an off-duty white police officer, has steadfastly maintained his innocence and is now demanding that a polygraph be administered before his execution. Three times before he's come within hours of being led to the death chamber, but after Georgia's parole board nixed his clemency bid on Monday his legal options are apparently exhausted. Even though there's a mountain of doubt over whether he actually committed the crime, it looks like this will be his last day on Earth.

In a way, it's fitting that the execution of a possibly innocent man is making headlines now, given the sudden prominence of capital punishment in the national political conversation -- the result of a recent Republican presidential debate, when the audience erupted in cheers at the mention of the 234 executions that Rick Perry had overseen as Texas' governor. Even some death penalty supporters said they were disturbed by that reaction, but it was also a powerful reminder of just how many Americans -- Republican or not -- see capital punishment as a simple matter of justice.

Gallup has found that support for the death penalty has remained consistent for the past decade, with Americans favoring it by a more than two-to-one margin. As of last November, 64 percent support it and just 29 percent oppose it. That number, however, is down from the late 1980s and early 1990s, when support for capital punishment peaked at 80 percent. It's also up from the mid-1960s, when death penalty support bottomed out at an all-time low of 42 percent. Back then, more Americans opposed it than favored it.

Why have the numbers changed over the years? The best way to look at death penalty may be to compare it to the country's violent crime rate, which not coincidentally took off in the mid-'60s, exploded in the '70s and '80s, then peaked in the early '90s and dropped substantially. The rate is considerably higher today than it was in the 1960s, but it's also nothing like it was two or three decades ago.

We can see the effects of this in our politics. Think back to the 1988 presidential election, when Republicans skewered Michael Dukakis over the matter of Willie Horton, a convicted murderer who had escaped while on a weekend furlough from a Massachusetts prison and fled to Maryland, where he committed armed robbery and raped a woman. The anecdote itself was damning, but one of the reasons the GOP attacks had such resonance was the soaring violent crime rate, which contributed to an atmosphere of fear and panic. Suburbanites fretted that all of the urban scariness that dominated the average local newscast would soon reach their bedroom communities and demanded to know from politicians: What are you going to do about it? The death penalty was a popular answer and became something of a toughness litmus test for would-be leaders, a test Dukakis famously flubbed in a debate.

It may have been the Dukakis example that Bill Clinton had in mind four years later, when he left the presidential campaign trail to oversee an execution in Arkansas. Human rights groups were enraged that Ricky Ray Rector, who was functionally retarded, could be put to death, but Clinton suggested he was setting an example for his fellow Democrats -- that they "should no longer feel guilty about protecting the innocent." Clinton's support for capital punishment featured prominently in his 1992 campaign, a way of reassuring Americans that he was tough on crime.

That, of course, seems like a long time ago now. Violent crime began dropping on Clinton's watch, and the issue faded from the national debate. Meanwhile, the late '90s and early 2000s saw a surge in coverage of the ultimate risk that comes with having a death penalty. New DNA techniques allowed old cases to be reopened, revealing tragic miscarriages of justice. When one particular death row inmate was exonerated in Illinois in 1999, that state's governor, Republican George Ryan, reacted with horror and emptied out death row. By 2004, Democrats felt OK nominating for president John Kerry, who had largely opposed the death penalty during his career, and in the last decade, several states have either outlawed capital punishment completely or rendered it functionally extinct.

Against this backdrop, it's tempting to wonder if the Troy Davis story -- which has received considerable press attention (and which will receive a lot more if tonight's execution goes ahead) -- might serve as a public opinion tipping point. But that potential is balanced against another reality: For all of the systemic flaws that have been revealed in the past decade or so -- for all of the innocent people who have been freed after years of incarceration -- the basic eye-for-an-eye nature of the death penalty remains compelling for most Americans, a sentiment reinforced by the occasional horrific crime. Take the state of Connecticut, where the gruesome murder of a suburban family in 2007 (which is still in the news, as the trial of one of the killers proceeds) apparently increased support for capital punishment in the state -- enough to convince the last governor to veto a plan to outlaw it.

The reality is that we have seen other cases like Troy Davis' before -- Perry may have presided over one of them just a few years ago in Texas -- and it will probably take a lot more of them before Americans ever give up on the death penalty for good.

Shares