The best TV commercial going during the playoffs is the Pepsi-Lay's potato chip ad in which four collegiate-type guys watch a football game on TV together. They go to comical lengths not to touch each other -- knees that accidentally meet jerk in opposite directions, hands that simultaneously land on a soda bottle recoil as though it were on fire. The camera cuts to a shot of the old alma mater scoring a touchdown on the tube, then back to the boys. They're having an orgy, rolling all over the couch, hugging for joy.

I'll leave it to those more familiar than I with the bizarre, deconstructionist thinking of the advertising industry to explain how this spot sells chips and soda pop, but what I'm really waiting for is someone more savvy about sexual identity than I to wade through the layers of meaning of this neat meditation on the repressed homoeroticism at the core of sports, and especially football, culture. Women's sports culture, of course, is a whole nother world, with its own fascinating, but totally different, issues around sexuality.

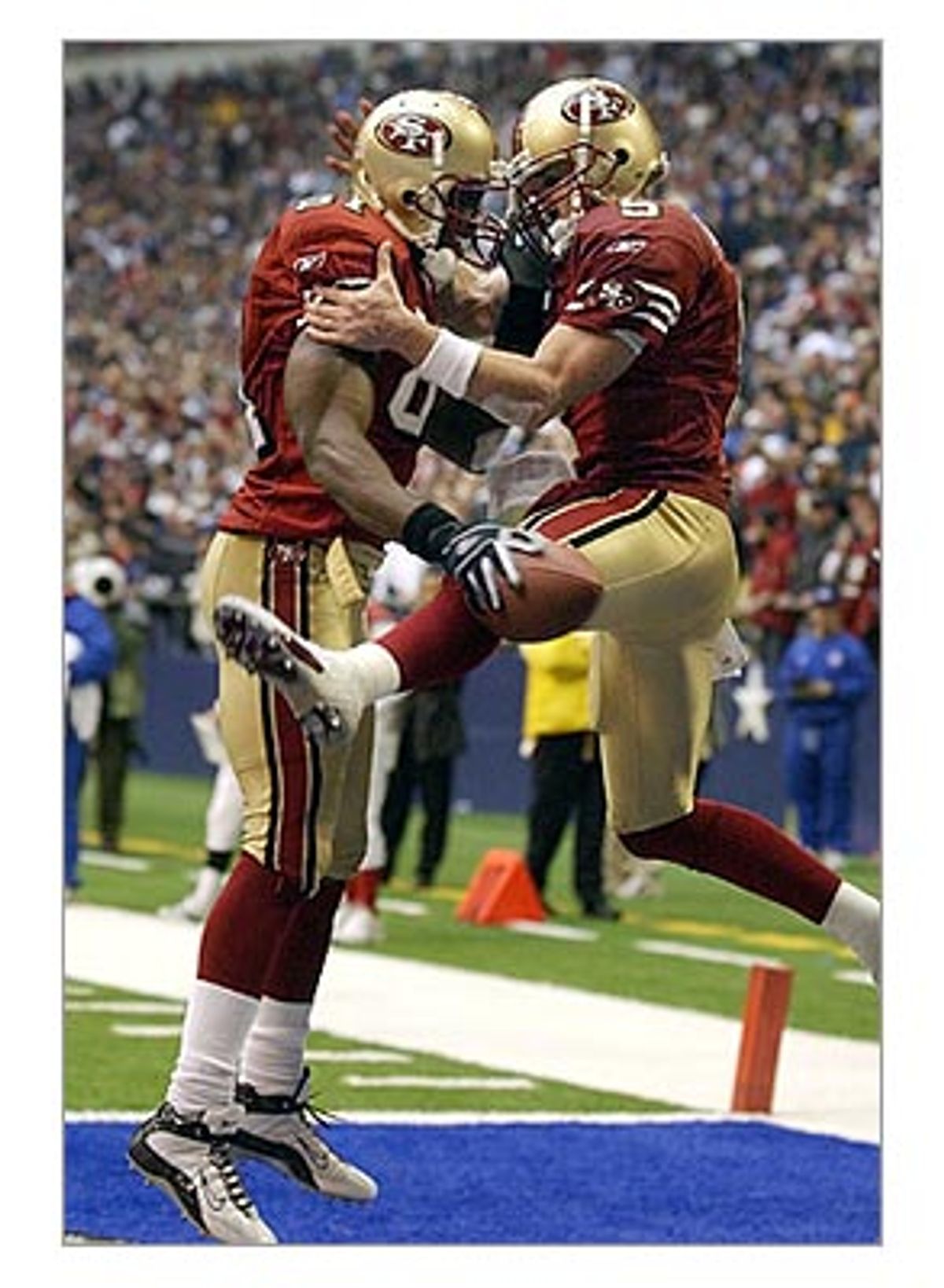

Within moments of one of this commercial's airings Sunday, Terrell Owens of the San Francisco 49ers scored a touchdown, and there was Garrison Hearst, hugging him, slapping fannies with him, doing that little forehead-touch thing that football players do that's as close as you can get while wearing a football helmet to kissing. This is the same Garrison Hearst who earlier this season responded to former NFL lineman Esera Tuaolo coming out by saying, "Aww, hell no! I don't want any faggots on my team. I know this might not be what people want to hear, but that's a punk. I don't want any faggots in this locker room." Hearst later apologized, unenthusiastically.

And that's the same Terrell Owens who two weeks ago scored a touchdown, grabbed a cheerleader's pompons and did a little dance. Jim Buzinski of Outsports.com called it "the gayest thing I've ever seen in the NFL."

Owens is not gay, unless he has a secret he's not telling us. No NFL player is publicly gay. Considering that there are more than 1,300 men in the NFL at any one time, it's a little hard to believe that they're all straight, but any gays there might be are so deep in the closet that Tuaolo has said that in his nine years in the league, he was never aware of a fellow homosexual player.

That's because the culture of pro football is decidedly homophobic. Take Jeremy Shockey of the New York Giants -- San Francisco's opponent Sunday. Right after the Tuaolo story broke, Shockey told Howard Stern and his listeners that he didn't know if he had any gay teammates, but "I don't like to think about that. I hope not." He went on to say that he "wouldn't, you know, stand for it" if he had known there were a gay player on his college team, because "they're going to be in the shower with us and stuff, so I don't think that's going to work."

Shockey apologized the next day, of course, saying he was just joking, which he clearly wasn't. What was notable was that he seemed genuinely surprised that anybody took offense at his remarks. In his world, Shockey's sentiments were mainstream thinking. Same goes for Hearst.

"The NFL is a supermacho culture," Tuaolo wrote in ESPN the Magazine. "It's a place for gladiators. And gladiators aren't supposed to be gay."

Which is precisely what makes it so fascinating that ballplayers spend so much time doing the things that straight men work so hard to avoid doing when they're not on the field, things like hugging and slapping each other's butts and holding hands and putting their foreheads together in tender gestures of affection. As in the Pepsi ad, straight men often go to great lengths to avoid even the most casual physical contact. You've noticed that empty seat between the two buddies at the movies or the ballgame, right?

The Pepsi commercial seems like a slight advance over a similar Heineken ad a few years ago. In that one, two guys in that same young male demographic are watching a game on the couch (of a very stylish split-level apartment, by the way, with track lighting). As in the Pepsi spot, we watch them from the point of view of the TV. One has gotten up to get a couple of beers, but he rushes back as his friend reacts to a great play. ("Go, baby, go! ... Up the middle! ... He's gonna score! He's in!" Whoa! Double entendre!)

The guy hurriedly plops down, practically on his friend's lap, and hands him his beer. As they both watch the game, yelling at the screen, nudging each other, the friend's hand closes over the beer-fetcher's hand, on the bottle. They stop yelling. The light changes. They gaze at each other. "This Magic Moment" kicks in. The words "The Male Bonding Incident" appear on the screen. Suddenly, the spell is broken. The boys quickly scoot to opposite ends of the couch and make these cartoonish stretching movements as if to show that their huge muscles are tightening up or something. Then their eyes meet again. They chuckle nervously, cough and scooch even farther away, practically off the couch. "You know what this game needs?" one says as the screen goes black. "More cheerleaders!" "Oh, yeah, more cheerleaders," the other says.

Because hey, we're not gay or anything!

Neither spot strikes me as particularly homophobic. Both make fun of that silly straight-guy fear of appearing to be gay. The slight progress is that in the old beer ad, the guys have their "male bonding" moment, then act all embarrassed and in denial. They talk about cheerleaders to prove that they're absolutely, positively, not queer. In the newer soda spot, the guys are self-conscious and embarrassed at first, but as we leave them, they are men loving men. "It's not whether you win or lose," the titles say, "it's how you watch the game." Yeah, baby.

That progress, however slight, is a good thing, and it's indicative of a more general progress toward the eventual acceptance of gays in sports, a subject that bubbled up in the mainstream culture last summer when New York Mets star Mike Piazza denied published rumors that he's gay, which had intensified after his manager, Bobby Valentine, said in a magazine interview that baseball was "probably ready for an openly gay player."

"There absolutely is" progress, says Cyd Zeigler Jr., the co-founder with Buzinski of Outsports.com. He cites the national conversation sparked by the Piazza story, "and Esera Tuaolo really bringing it home and saying, 'Uh, whether you think so or not, you've been playing with gay players, and I'm one of them.'"

Hearst and Shockey probably don't feel any differently about gays than they did six months ago, and most likely their teammates don't either. But they all saw what happened when Hearst and Shockey voiced those ugly opinions. Even if the bigots keep their mouths shut out of political correctness, that's a step in the right direction. We're one step closer to a time when an openly gay football player can hug his straight teammate in the end zone, and it'll just be two football players celebrating a touchdown.

Shares