It's the summer of 2001 and the video game industry is bigger and hotter than ever. In the feverishly contested hand-held market, Nintendo's GameBoy Advance and Atari's 2600-compatible VCSp are the must-have consoles. But fans are also eagerly awaiting new releases for popular consoles, like Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty for Sony's PlayStation 2 and Elevator Action for the Atari 2600.

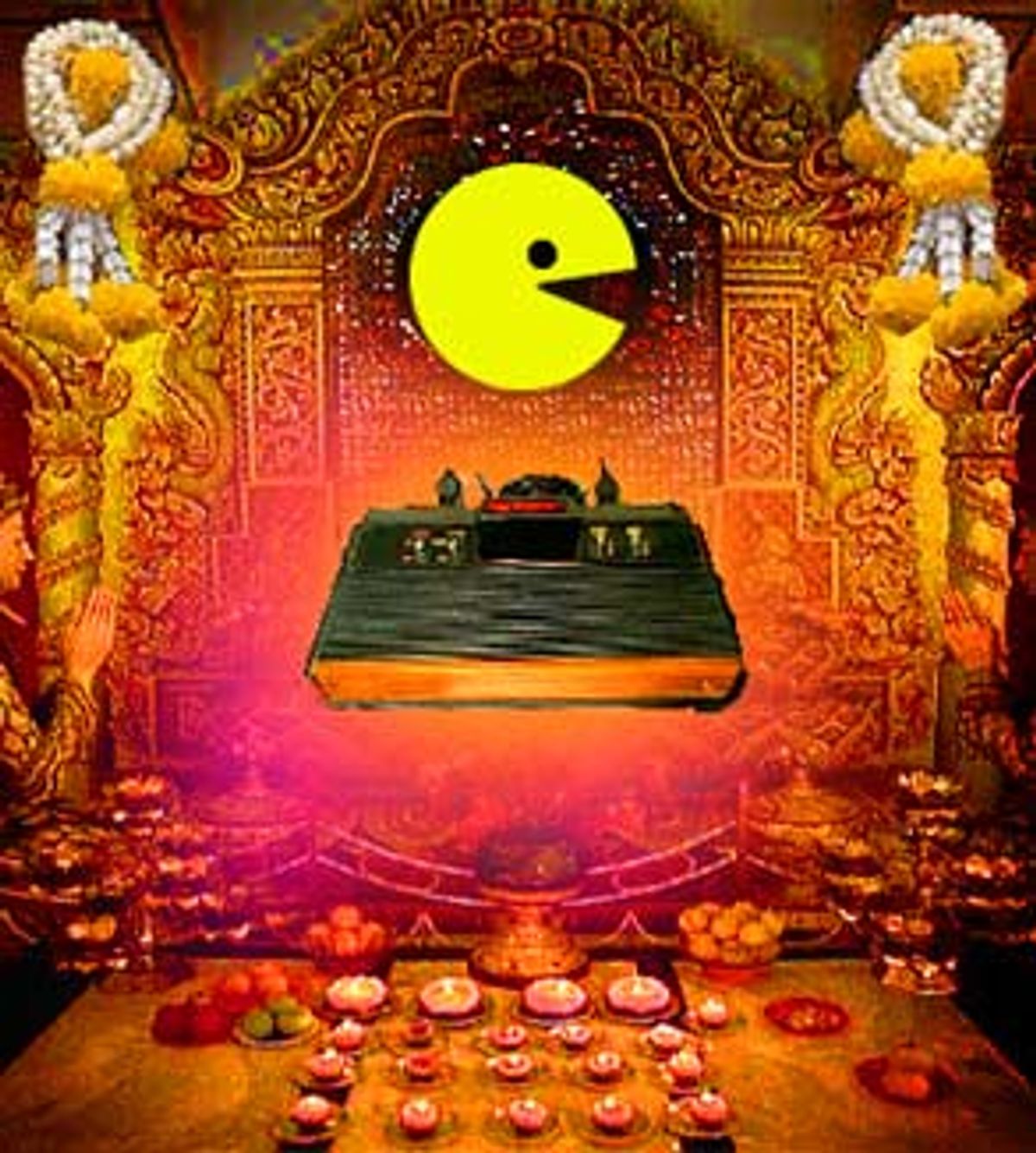

Wait just a second. Elevator Action for the Atari 2600? In the 21st century? Isn't the Atari 2600 the archaic console that only plays those games with the rinky-dink graphics and sound and simplistic play, like Combat and that godawful version of Pac-Man? The one with the goofy pseudo wood-grain trim on its casing that started the whole video game console market 24 years ago?

Yep. The Atari 2600 ceased production in 1989. But practically speaking it never really went away. The abandoned system has been adopted by online fans, who nurture it with loving care. And they're doing more than just keeping it on life support; the Atari 2600 is actually growing -- new games are being written, and new hardware is being manufactured. Affection for the system and its classic games may be strongest among those who were kids or teenagers during its heyday, but even though the 2600's technology is Neolithic compared with present-day systems, it's still gaining new fans. Some are programmers who want to test their skills against the severe restrictions forced by primitive hardware. Some are attracted to games that emphasize playability over whiz-bang graphics. And some just think the system's hip.

The Atari 2600 certainly used to be the hippest console on the block. Long before the PlayStations and Dreamcasts and GameBoys ruled, the Atari 2600 (also known as the "VCS" for "video computer system") was king of the consoles. During the so-called golden age of console gaming, from 1977, the year when the 2600 first appeared, to 1983-84, when the gaming market crashed thanks to a glut of lousy games and bad marketing decisions, Atari was preeminent. Over its 11-year production life span the 2600 sold more than 30 million units, far surpassing its major competitors, Intellivision and Colecovision.

That dominance survives. "The 2600 is far and away the most popular classic system," says Alex Bilstein, a 29-year-old Web developer in Austin, Texas, who is one of the webmasters of a popular Web site dedicated to the Atari 2600. "Every system has its following, but I don't think any compare to the VCS, partly because it was popular in its lifetime and is therefore nostalgic for a lot of people. 'Atari' is retro-cool in certain youth groups today."

In an era when realistic 3-D graphics and sound and complex game play are the norm, the question of why there is still a significant following for the ancient 2600 may strike many gamers as mystifying. Yet to those who keep the faith, interest in the technically simpler Atari 2600 has been growing precisely because gaming technology is now so darn sophisticated. Many 2600 games are simple to learn, which makes them appealing to certain groups, says Bilstein: "People who normally wouldn't touch a video game will play a game of Atari because you don't have to learn a complicated manual in order to play. My mom can play Space Invaders."

Atari's popularity is far from confined to Space Invaders fans, however. What makes the Atari revival unique is the amount of active software and hardware development that continues to this day on the platform. Perhaps most amazing, today's Atari fans can buy a hand-held 2600, the VCSp, that uses the old 2600's game cartridges. Its inventor, Benjamin Heckendorn, builds each unit for his customers by hand, and says he is having difficulty keeping up with demand. Another community effort currently underway is to devise step-by-step building plans so that nostalgic hardware hackers can build their own 2600-compatible game consoles from scratch.

No console can survive without games, however, and it is in the software arena that the online 2600 enthusiasts are concentrating most of their energies. Some programmers have even taken it upon themselves to write new games for the platform. While such "home-brew" games are written for the other classic game systems by their fans as well, there's simply more interest in game programming for the Atari 2600.

Bob Colbert, a 34-year-old systems analyst in La Vista, Neb., fulfilled a lifelong dream when he wrote a game for the 2600. Using information about the console that he found on the Web, he created a puzzle game called Okie Dokie -- one of the 2600 revival scene's first home-brew games. His original intent was for it to be played using software-only Atari 2600 emulator programs that are freely available, but he received so many requests for Okie Dokie in cartridge format (so that it could be played on actual 2600 consoles) that he produced a limited-edition run of 100 cartridges. That didn't even begin to meet demand, but he couldn't keep up production. ("The cartridges took a lot of time to make," he says.)

Don't be deceived by the simple look of these games -- programming the 2600 is actually quite tough. "Making any discernible graphics display on the 2600 is difficult," warns Colbert. Home-brew game makers are rediscovering the hurdles that the original programmers who were hired to make games for the system faced -- a system with a mere 1 MHz CPU and 128 bytes of RAM does not allow a lot of room for sloppiness or error. Creating a good game for the system requires a keen sense of technical resourcefulness. Undaunted, most of the newfound game developers see taking on the 2600 as a kind of Zen exercise in which programming skills are put to the ultimate test.

Joe Grand, a 25-year-old in Boston who works in computer security, can attest to this challenge from his experience making his 2600 game, SCSIcide. He points out that "the hardware was originally designed to play Pong-type games." But during the system's latter years, after the golden age of video games ended, titles like Pitfall II and Klax featured impressive graphics, sound and game play. Grand is still in awe:

"The programmers stretched the hardware to limits unintended and unimaginable even by the hardware designers! A lot of times while I'm programming, I'll throw on some disco music, pretend it's 1979 and imagine what the designers had to work with," says Grand. "The design/debug cycle was much more drawn out then, and the programmer couldn't just write some code, compile it and immediately test it on an emulator as we do now."

Making their own games isn't the only way that 2600 fans satisfy their jones for new Atari thrills. Some in the scene have taken it upon themselves to hunt down fabled "lost" titles -- prototype games developed years ago by Atari and other companies that were never released for sale. Several prototypes have been discovered over the past few years.

A prototype tends to turn up when the programmer who worked on it reveals its existence to the 2600 revival scene, or when a collector happens to find a prototype cartridge at a thrift store or acquires it through someone who once worked for a company that made games for the system. Once the existence of a lost game is confirmed, the goal among the gaming community is to politely encourage the person in possession of it to "dump" the code in the cartridge to software form so that it can be played on an emulator and freely enjoyed by others.

(There are obvious copyright issues associated with releasing old games on the Net, even if they have never been commercially marketed. If the company that made the game is still around, permission might be sought. Or a game's original programmer(s) might be asked if the code can be released.)

Bilstein's Web site, AtariAge, has introduced several prototypes to the public, including Kabobber, a fully playable game from Activision that was never published by the company. Games based on the comic strip "Garfield" and Disney's "Snow White," an incomplete but playable translation of arcade classic Tempest and even a sequel to Combat, the game that originally came packaged with the 2600 console, have all turned up in the past two years. The aforementioned Elevator Action was a recent discovery; cartridge versions of it, complete with old Atari-style packaging, will be sold to the public at the Classic Gaming Expo in August.

"There's a surprisingly large number of prototypes available for the 2600, certainly more so than for any other system," says Albert Yarusso, a 31-year-old programmer who has worked in the modern-day gaming industry at Looking Glass Technologies and Ion Storm. He runs the AtariAge Web site with Bilstein. "When the market crashed in 1983, most companies were very active in 2600 development. There were many finished (or near-finished) games that never made it to store shelves because of the crash. Looking through the database we have at AtariAge, there are around 70 prototypes listed for the 2600. Amazingly, new prototypes are still being discovered to this day."

Several highly sought-after prototypes have yet to be found. "Holy Grail" titles include games based on "The Lord of the Rings," "The Incredible Hulk," "Rocky and Bullwinkle" and Dungeons & Dragons, as well as 2600 versions of classic arcade games like Scramble, Turbo, Zookeeper and more. Bilstein believes some of these titles will eventually be discovered. "Just as a wild guess, I wouldn't be surprised if 10 to 20 more turned up," he says. "At least 10 games were seen at [consumer electronics shows] back in the '80s that nobody has been able to find, so they may just be waiting in a storage locker somewhere."

Atari's future may extend beyond the revival of prototypes and the creation of simple new games for hobbyists. Some Atarians predict the emergence of 2600-style games made to appeal to a broad audience. During the golden age of video games, a single person could program an entire game for the 2600. With today's state-of-the-art consoles, such video game auteurism is an impossibility. But Bilstein says, "I see a parallel between classic games and mobile gaming, as it requires fewer people to design the small games that mobile gaming requires. I know a few classic-era game programmers who went into [mobile gaming development] because they enjoy being the sole developer of a project."

There may be a market opportunity here. International video game publisher Infogrames, the latest company to own the Atari name and its games, recently announced that it will bring Atari classics like Asteroids and Missile Command to PDAs and Java-capable cellphones. The simple game play and graphics of such games lend themselves well to these devices. Mobile gaming is projected to grow in the next few years, and Infogrames is one company looking to capitalize on the moment.

Above all else, Atari 2600 aficionados believe that their favorite console remains relevant because there are lessons about making games for it that every developer for more technically advanced consoles needs to be reminded of: Keep it simple and remember that it's all about the play. "While most of the 2600 games may not be very aesthetically appealing, they have [what] counts: Namely, they're fun to play!" says Yarusso. "It should be mandatory to sit and play through the best games of the 2600 library before designing games for modern systems."

Shares